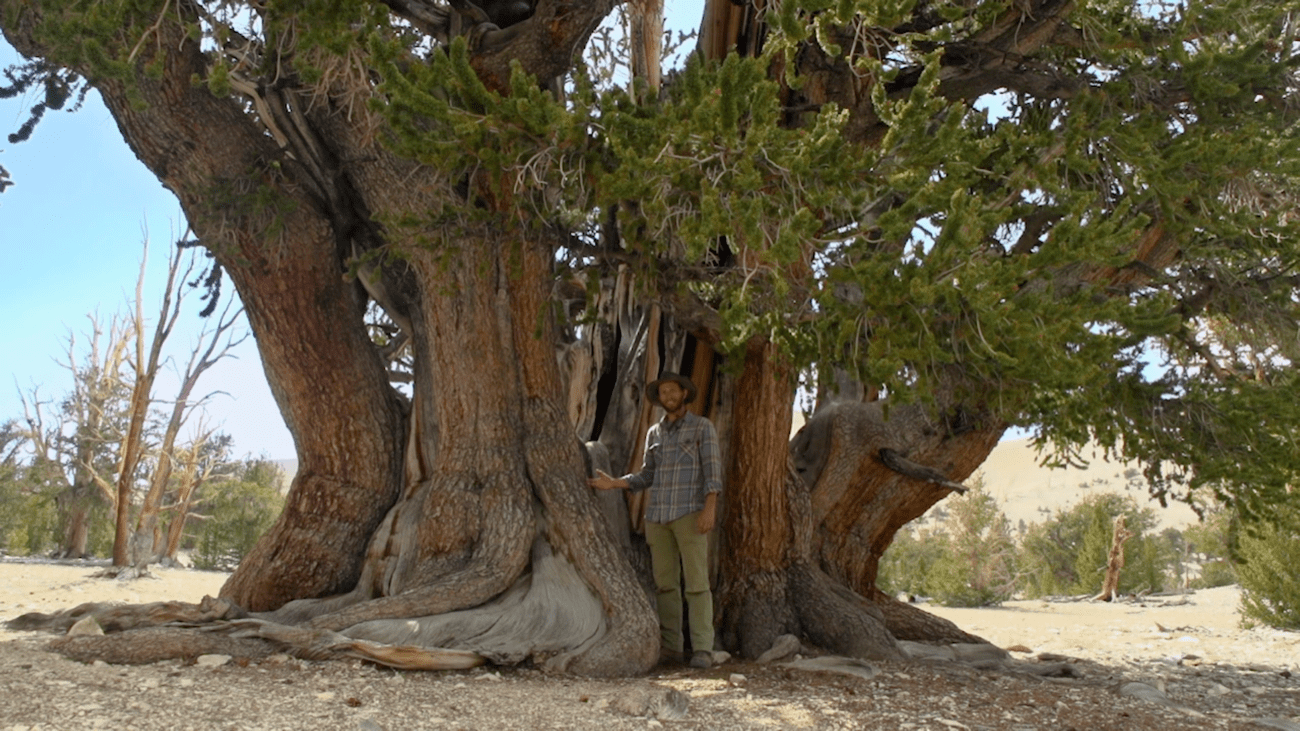

Brian Smithers, a researcher assistant professor at Montana State University, is standing in front a massive tree in California’s White Mountains, an arid range near the edge of the Great Basin.

“It’s been around for quite possibly longer than the entirety of Christianity, never mind Western civilization,” he says.

The tree is the bristlecone pine, known for thriving under harsh, dry conditions. The species is also known for its extreme longevity. “We’re talking upwards of 5,000 years,” says Smithers.

The key to the tree’s long-lived lives is its incredibly slow growth, which results in very dense wood. The dense wood is useful—the trees can withstand insects, rust, and winds up to one hundred miles per hour.

The bristlecone pine’s germination process, like the environments it thrives in, is unforgiving. “They produce a ton of seed, but the vast majority will just get eaten by chipmunks or ground squirrels,” says Smithers. Even the seeds that do survive the animals will almost certainly die as well due to the harshness of the climate, since they need very specific conditions to germinate and thrive. But as Smithers points out, “If you live for say 3,000 years, all you need is one or two of those individuals over that time to make it. It is the definition of perseverance. It’s why I got into these trees.”

The question is how these trees will struggle, or thrive, with a changing climate. As the climate warms in this region, the bristlecone moves upslope to continue to live in its ideal temperature range. “Our research has shown about a 20 meter vertical upslope average increase over the last 50 years,” Smithers says.

But the mountaintops are already crowded with both with bristlecone pine and some upstarts who want to move into the neighborhood. Limber pines are another tree in the harsh region that usually live further downslope. The species is long-lived, but a relative sapling compared the bristlecone pine—it can live roughly between 1,600 and 2,000 years.

Both bristlecone pine and limber pine seeds are harvested by a bird called the Clark’s nutcracker. As it flies, it spreads the seeds across the landscape. Unfortunately for the bristlecone pine, the Clark’s nutcracker prefers seeds from the limber pine—and as climate change warms the region, the limber pine is more likely to germinate in what was traditionally bristlecone pine territory. “There’s this entire area of new, undeveloped real estate that is now climatically available. Limber pine is just able to get there more quickly,” Smithers says. “It’s actually jumping right over the bristlecone pine and charging upslope.”

Given the new competition, Smithers is uncertain about the future of the bristlecone pine.

“As a species, they’ll have to make some adjustments,” says Smithers. “Bristlecone pine has weathered many climate changes. They’ve been getting punched in the face their entire species history and even, in some ways, thrive in the face of adversity. But whether they can make those adjustments in their range fast enough to keep up with climate change, I think that’s the question.”

Donate To Science Friday

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Credits

Produced by Luke Groskin

Filmed by Christian Baker

Music by Audio Network

Additional Footage Provided Shutterstock, Adobe, Youtube User “aGuy” (C.C.BY 3.0)

Meet the Producers and Host

About Luke Groskin

@lgroskinLuke Groskin is Science Friday’s video producer. He’s on a mission to make you love spiders and other odd creatures.

About Dee Peterschmidt

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.