Inside The ‘Creepy’ Procedure That Taps Into Young Blood

12:00 minutes

This Halloween season brings quite a few vampire offerings, like the new adaptation of Stephen King’s “‘Salem’s Lot,” the “Nosferatu” movie coming out in December, and the final season of “What We Do In The Shadows.”

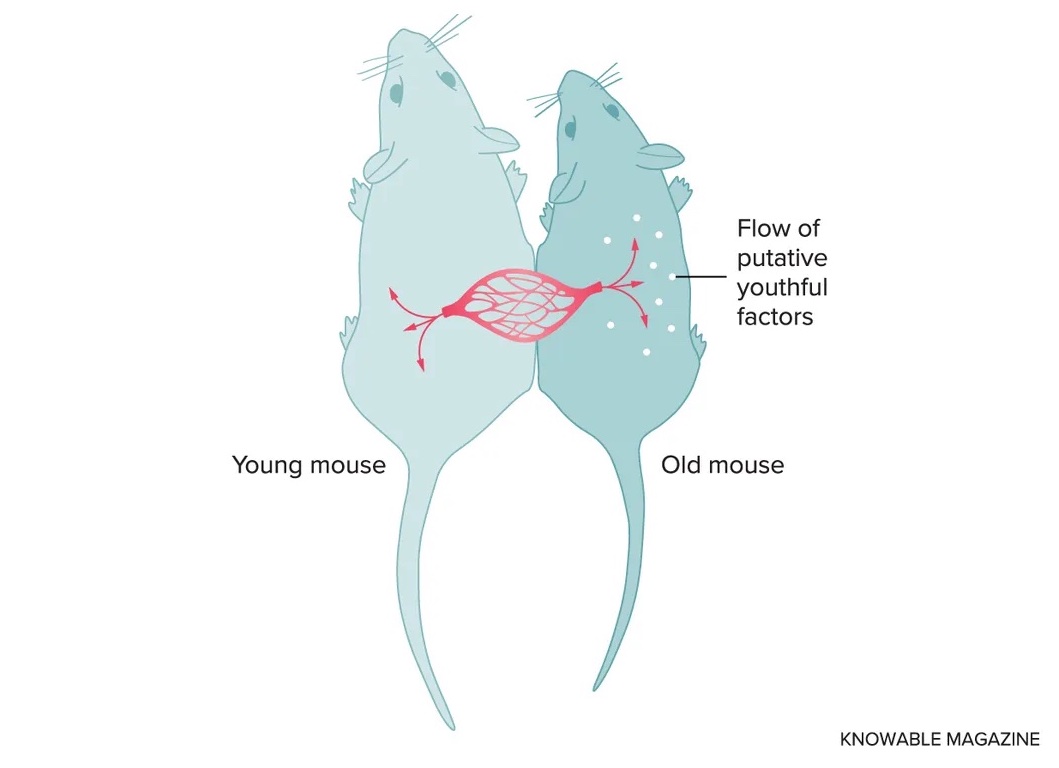

While fictional vampires suck the blood of the young to live forever, some researchers have found that certain elements in young blood actually can improve the health of the old. This is possible through a spooky procedure called parabiosis, in which the circulatory systems of two animals are joined, letting the blood flow from one into the other.

By connecting old mice and young mice through parabiosis, researchers have observed how different molecules in the blood impact symptoms of aging. While some outcomes have excited experts, enthusiastic biohackers attempting to defy their own aging might have jumped the gun. There’s a long way to go before we understand how elements of young blood might be harnessed to treat aging humans.

Emma Gometz, SciFri’s digital producer of engagement, talks to Dr. Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurology professor at Stanford University who has used parabiosis (which he once described as “creepy”) to help reveal how components of our blood affect our cognition as we age. They discuss parabiosis, vampires, and how far the field has to go before humans can benefit.

Dr. Tony Wyss-Coray is a professor of neurology at Stanford University in Stanford, California.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: To close out the hour, it’s officially Halloweekend. I’ll be celebrating with a spooky movie. And I noticed we have quite a few new vampire offerings coming out. There’s the new adaptation of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot, the Nosferatu movie coming out in December, and my personal favorite, the final season of What We Do In The Shadows. And just as vampires suck the blood of the young to live forever, some researchers have found that certain elements in a young person’s blood can actually improve the health of the old. This is possible through a spooky procedure called parabiosis, where the circulatory systems of two animals are joined, letting the blood from one flow into the other.

That procedure has found its way into movies and TV as well, like in this clip from HBO’S Silicon Valley.

ACTOR: Uh, is Bryce your assistant?

ACTOR: No, of course not. He’s my transfusion associate.

ACTOR: Which is?

ACTOR: Are you really not familiar with parabiosis?

ACTOR: I can’t say that I am.

ACTOR: Well, the science is actually pretty fascinating.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Emma Gometz, SciFri’s digital producer of engagement, who writes our Science Goes to the Movies newsletter, sat down with a neurologist who’s used this technique to research aging and the brain.

EMMA GOMETZ: Here to tell us more is Dr. Tony Wyss-Coray, a professor of neurology at Stanford University. Welcome to Science Friday.

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Thank you for having me.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So you’ve said that talking about parabiosis is a bit creepy before and it reminds some people of vampires. Why is that?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: That’s right. Well, just the idea that two animals would be sutured together at their flank sounds a bit spooky. And even though it’s 100 years old, I think it’s still something that not everybody would feel comfortable about.

EMMA GOMETZ: And could you just tell us, what is parabiosis? And who came up with it?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Yeah. So this is a technique that was invented over 100 years ago by Paul Bert, in France. And the initial idea was to test whether animals could share their tissues. And the model has really had a big impact in transplantation of tissues that we now take for granted. It also led to the discovery of sex hormone, or an obesity hormone, and more recently, it has been used to study aging.

EMMA GOMETZ: And so why is there a need to use this procedure in research at all? What health conditions does this benefit?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: So it’s not directly a health benefit, but researchers have wondered whether something in the blood might be associated with age. So, in other words, is the blood from a young animal, for example, or a young person different from that of an old one? And indeed, we see that the composition at a molecular level is very different between young and old people, between young and old mice. And so people, then, in the aging field wondered, what if we would expose an old organism– specifically old stem cells– to a young circulation– to factors from the young blood.

The way I got into it is really from my interest in understanding Alzheimer’s disease. And one of the key drivers of this disease is age. And we noticed that the composition of the blood changes dramatically with age. And so when my colleague, Tom Rando, made these discoveries, that blood from young animals is beneficial for muscle regeneration, we wondered, of course, could the same be true for the brain. And he had indeed some hints that this might work. So that’s really how we got into it, and then wanted to understand better what are the factors, and is old blood detrimental for young ones, and so forth.

EMMA GOMETZ: So you mentioned these factors in young blood– like elements in the blood of young people. Can you explain what they are and how they affect our health as we age?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Yes. So we haven’t really discovered enough about what exactly these factors are. My lab and others have focused on proteins specifically. And we see many proteins change in concentration from young to old. And some of them seem to have beneficial effects on the body. They maintain tissues. They maintain stem cells. And then we also find accumulation of factors that seem to be detrimental, that accumulate with age, some of them involved in inflammation.

EMMA GOMETZ: Right. So just so I’m understanding this, you find this out by circulating the blood of a young animal into an old animal, and then you can see how that affects the older animal?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: That’s correct. So technically, you actually only suture the animals together at their flank, at their skin, and then blood vessels grow into this wound. And so you have a connection between the two circulatory systems. It’s a very slow exchange. But we showed later on, actually, that you can simply collect the blood of a young animal and then infuse it into the old one and reproduce some of the same effects.

EMMA GOMETZ: So you specifically study how these circulating factors can affect our brains and our cognitive functioning. So what are you researching right now related to that?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: So we’re really interested in how the brain ages. And working together with Tom Rando, we asked whether these effects that he saw on the muscle would also apply to the brain. We identified some factors that are detrimental, that accumulate with aging, and we can block them, and, at least in mice, show that this benefits the old mouse. And also, as I mentioned earlier, we can transfer young blood into old mice. And the mice show improvements at molecular levels, at the cellular level, and then, most importantly, their memory function becomes better and more like a young animal.

EMMA GOMETZ: Oh, OK. Can you tell me a little more specifically what you mean by improvements? What about it changes?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Yeah. So as people get older, and especially if they get cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, one of the characteristics is that they lose spatial orientation. So they may get lost in their neighborhood, taking a walk. And interestingly, we see the same in mice. So you can imagine, a mouse must be able to find where its nest is or where it was hiding some food or things like that. And as the mice get older, they have similar deficits. And we can actually quantify them. We can measure them. There’s a number of different memory tests that have been developed for mice. And as they get older, they get impaired in these tests.

And what we showed is that, if you give an old mouse infusions of young blood, then they do better, again, in these tests and show improvements in function.

EMMA GOMETZ: Wow. That does kind of remind me of a vampire, I got to say. So does this go the other way? Does circulating old blood from older mice into young mice do anything? When you create parabiosis, does the blood flow both ways, or does it only go from one to the other?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Yeah, that’s a fantastic question. So, indeed, what we see is that the old blood is actually detrimental for a young organism, and it induces impairments and mimics aging to some extent. So we have now tools that allow us to measure molecular changes that are associated with aging. And we can show that old blood can accelerate these aging changes at a molecular level. And also, at a functional level, it can cause inflammation. And then, as I said earlier, the young blood can reverse some of these effects in older animals. So it really goes both ways.

EMMA GOMETZ: So parabiosis is done mainly on mice, like you said. But how close are we to using the results of this research to develop treatments for humans? And what would that even look like?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: So one approach would be to try and use blood donations from young individuals and give them to people with Alzheimer’s disease, for example. And indeed, that’s what we did in studies, together with industry– could show that, at least in early stage trials, that this is well tolerated and might be beneficial. This is something, as you know, in the hospital, blood donations are used all the time, whether it’s for if you lose blood in surgeries, but sometimes also exchanging blood if people have autoimmune diseases. And then, people who are immunodeficient, they get parts of fractions that are isolated from blood donations. So it’s something that is very frequently used already in the clinic, and it’s possible that this could be adapted.

The other direction is, of course, to try to find what are the individual components, what are the individual factors, and then produce them synthetically, as we do for other drugs, and apply them for the treatment of age-related diseases.

EMMA GOMETZ: Wow. Parabiosis and research on young blood has popped up a lot in the media, like the Silicon Valley clip we played earlier, or even among some enthusiastic biohackers who get blood transfusions from the young. Does this actually work for humans?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: We don’t know yet. There are studies underway. There’s a study in Norway that is testing this. And we did studies earlier in just small numbers of individuals to test whether young blood– blood from young people– could be beneficial for patients with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. But the results are still out. So we really need large clinical trials that are controlled with placebo so that we can figure out, does this really work.

EMMA GOMETZ: So it’s a “don’t try it at home” situation right now, right?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: Exactly. Don’t do it in your kitchen.

EMMA GOMETZ: OK. And where do you see this field going in the future?

TONY WYSS-CORAY: I think one of the key directions has to be to figure out what are the components. We know now it’s not going to be one factor that can do it all. We know from studies– very broad studies, where we interrogate every cell in the body of a mouse and see how does it respond to old or young blood– that different cells respond in different ways to factors, suggesting that you would probably need more than one factor if you want to have very broad benefits– almost like a cocktail.

The alternative is to find factors that are beneficial for one tissue. So if we could find a factor that is particularly beneficial for the brain, that might still lead to the development of a drug based on these discoveries.

EMMA GOMETZ: This has been a really enlightening conversation, but I definitely do think it’s still a bit spooky. Do you have a favorite vampire movie or anything? Are you a spooky guy?

[LAUGHTER]

TONY WYSS-CORAY: I don’t know what that means. I don’t have a favorite vampire movie. But yeah, it certainly fits the season.

EMMA GOMETZ: Definitely. Well, thank you so much for your time. This was a lot of fun.

TONY WYSS-CORAY: It was great. Thank you.

EMMA GOMETZ: Dr. Wyss-Coray, professor of neurology at Stanford University.

If you’d like to read more about parabiosis and check out how it connects to a vampire movie that just came out, you can go to sciencefriday.com/vampire. I’m Emma Gometz.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Emma Lee Gometz is Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. She’s a writer and illustrator who loves drawing primates and tending to her coping mechanisms like G-d to the garden of Eden.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.