You Are How You Read

17:18 minutes

As a graduate student, neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf loved the novel The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse. Years later, she returned to the book she had loved so much, but soon discovered that she no longer appreciated the writing. The act of reading became too slow, the prose too dense. She described this realization as a moment of utter panic: Had she fallen out of love with Hesse?

More likely, it was her reading brain that had changed. These days, we experience most of what we read online, and that has made us excellent skimmers and multitaskers. But we’ve gotten worse at the kind of reading that requires critical thinking and analysis, referred to as “deep reading.”

As Wolf describes in her newest book, Reader, Come Home, we may be at risk of raising a generation of people who don’t have those skills simply because of our changing reading habits. She joins Ira to discuss how our reading brain has changed since moving into the digital world and what we can do to fall in love with reading again.

Maryanne Wolf is the director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Has this ever happened to you? You return to a book you used to love reading, and suddenly– well, it’s lost its magic. The writing is complicated. The prose is dense. You just can’t get through it.

So what’s going on here? Have you fallen out of love with Proust? More likely, it’s your reading brain that’s changed– your reading brain. These days, we’ve experienced more of what we read online. And that has made us excellent skimmers and multitaskers. And maybe Proust is not really your cup of tea anymore.

But according to my next guest, not so good at a kind of reading that requires critical thinking and analysis, even considering other people’s point of view. That’s what happens when we are reading online.

My next guest says we’re at risk of raising a generation of people who don’t have those skills simply because of how we read. So I ask you, do you notice a difference in your reading style when you read something online versus in print? Give us a call. Our number– 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK. Or tweet us @scifri.

Maryanne Wolf is the director of the Center for Dyslexia, Diverse Learners, and Social Justice at UCLA. She is author of the new book, Reader, Come Home. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARYANNE WOLF: It’s my pleasure, Ira. You’ve long been a hero of mine.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Have you fallen out of love with Proust?

MARYANNE WOLF: Not at all, but I’ve had to recover it. So I’m a recovering Proust reader.

IRA FLATOW: What do you mean you’ve had to recover it? Tell me about that. You write in your book that you’ve had this experience– happens to you where you return to a book you’ve loved many years later. And you couldn’t read it anymore.

MARYANNE WOLF: Yes. I have written a series of letters in this new book. And in letter four, I acknowledge one of the more humbling experiences in my scientific life in which I made myself the single subject. And what happened was I decided since I’m telling so many people about how their brain is changing when they read, I thought I would simply look at myself. And that was the beginning of a rather terrible experience.

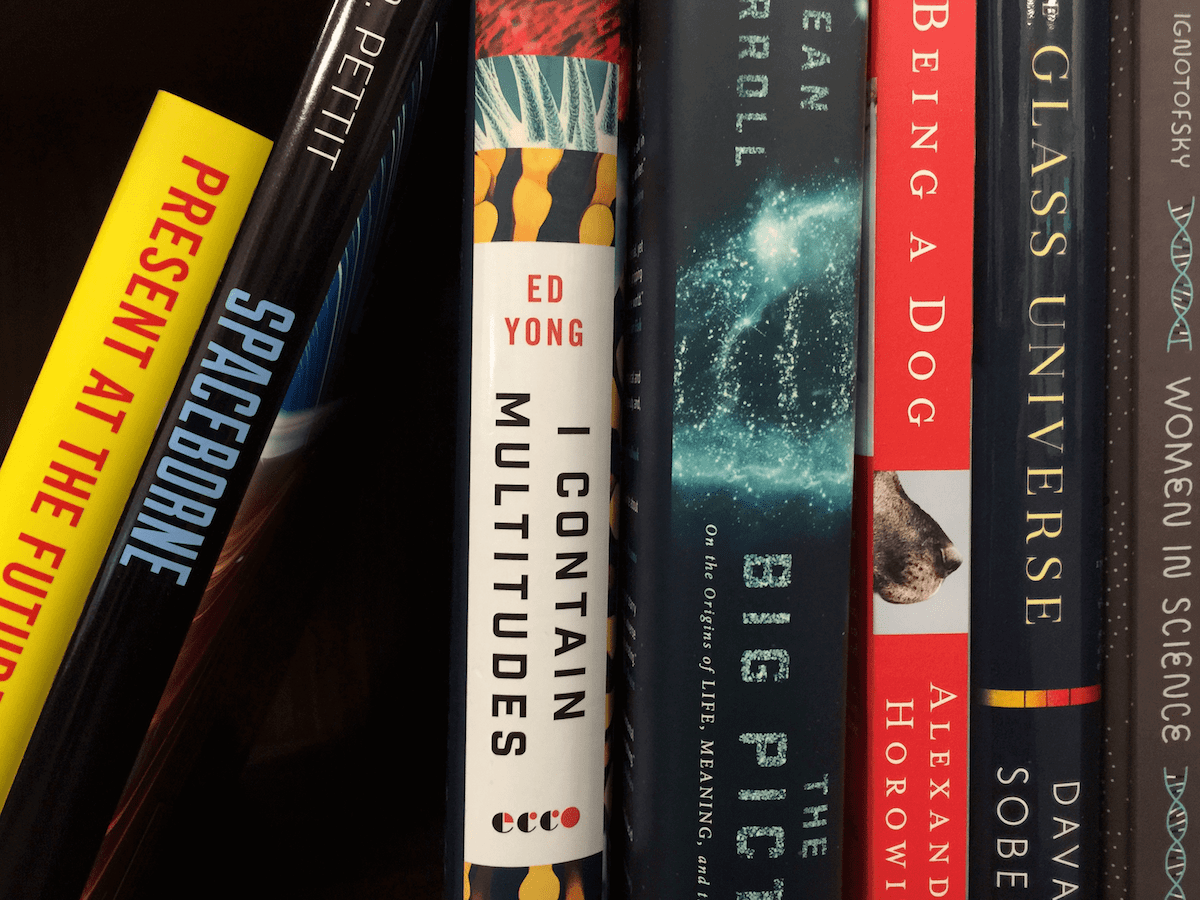

I picked up Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game, which once was one of my most favorite pieces of literature. And Ira, I simply couldn’t read it. It truly felt like I was pouring molasses over my cerebrum. And it was so humiliating.

I thrust the book back until I realized Hermann Hesse– all these people have been the friends of a lifetime. They have made me who I am. And so I determined to go back and read, but very differently, just read 20 minutes a day.

And Ira, it took 10 days for me to return to that mode of reading in which I could immerse myself and not be distracted by syntactic density or length or even the complexity of the arguments there. But it took a good 10 days to return home, if you will.

IRA FLATOW: And you attribute that to the fact that you were doing more reading online versus reading in a book? That’s one of the theses of your book– is that we are wrecking our reading habits and wrecking a lot of other stuff because we’re reading online now instead of reading from a paper.

MARYANNE WOLF: Well, it begins with a statement. And it’s very important that your listeners and my readers understand that I’m not making a binary argument. I am saying, however, that because the reading brain is plastic, we never were meant to read. We had to form this beautiful new circuit.

But because it’s plastic, it reflects things like the writing system. A Chinese reader is different from an English alphabet reader. But it also reflects the medium. So the dominant medium is going to be reflected in the style of reading. Even when you’re not reading on the screen, it will affect you as you read print.

And there are good reasons for that. Quite literally, our circuit– it’s like a mirror held to the processes needed by any medium. So if a print medium is giving us precious though imperceptible time to allocate milliseconds to inference, the scientific method processes, critical analysis, immersion, that’s the advantage of print that we think will be just continuous no matter how we read elsewhere.

But it’s not the case. The advantages of the screen, which are hastening us along, multitasking, being ready for the next novel experience– that ends up making us skimmers. And skimmers literally skim what I call the “deep-reading processes” that involve critical analysis and empathy and even insight.

IRA FLATOW: And you say that whole idea about skimming and because we’re not doing critical analysis and insight– you say that’s actually a threat to democracy.

MARYANNE WOLF: It was the last thing in the world– that as a cognitive neuroscientist I would be thinking I’m actually confronting implications for democracy. But the reality is that one of the most precious aspects of deep reading is that we give time to inference. We give time to critically analyze and evaluate the truth of what we’re reading. And this is often neglected in understanding reading. Reading gives us an opportunity to engage our feelings of empathy and also our engagement with alternative viewpoints.

And one of the things that I will never forget was an interview between former president Barack Obama and the beautiful novelist Marilynne Robinson about the power of reading to give empathy. And Obama said, the novel is what has taught me moral and ethical development. It taught me about other, to which Marilynne Robinson said, the trend towards seeing others as sinister others is one of the greatest threats to our democracy.

And I’ll end this little part of our discussion, Ira, with a quote from Jane Smiley or a paraphrase in which she was asked about the novel and empathy. And she said, the novel is not going to die. But it may be sidelined. And if it is sidelined, we will be led by people who do not read, who do not understand fully the feelings and the minds of others, leading us to a potential new era of barbarism.

IRA FLATOW: So when you say reading online, you are making a distinction between reading websites, places like that, and reading a book that might be a Kindle or an ebook or something like that, correct?

MARYANNE WOLF: You know, this is a really important distinction, Ira. There are different modes of reading. And we need to understand that even the Kindle, which is far better than reading in a distracted, internet-type computer environment or screen environment– even though that’s far better, you still have three problems.

You have a set towards the screen, which is the set or anticipation of evanescence, of transitory images. So you end up still having this set towards speed, hastening along. And in addition, the second and third parts are you don’t have that concrete, kinesthetic element that actually is activated in your brain and slows you down to allocate more time to these other processes.

And you do not ever have what is called “recursion.” You can’t return to monitor what might not have made sense a few minutes ago. In a screen, even in a Kindle, even though it is possible to return, you do not. Therefore, your comprehension monitoring on a screen, while far better than a computer, actually has some of that transitory, imagistic element that makes you speed faster than you would in a print form.

IRA FLATOW: A lot of folks want to comment on this. Let me see if I can get a call or two in. Let’s go to Andrew in Cleveland. Hi, Andrew.

AUDIENCE: Hi. Wow. It’s one of those moments where I’m listening on the radio, and I now have more questions than I came in with. But I work in a variety of schools all over Northeast Ohio as a substitute teacher. And I’m often seeing students who– the one thing you lament, especially at the high school level, is reading their literature assignments. And admittedly, some of those books are harder to get through.

I’m a big advocate with them for using audio books as a means of getting their material covered. And I’m curious if your guest sees that as another step down the slippery slope or if having a human voice reading to you is a step in the positive direction.

And while I was listening, I was curious. Is there any data on students that are taking tests via computer as opposed to tests on paper, their reading and retention of those questions? And is there any indication that one is better than the other or more harmful?

IRA FLATOW: All right, Andrew. Thanks for that. What about being read to?

MARYANNE WOLF: Right. This is a beautiful question that I’m often asked. And I liken many of our young as not necessarily deep readers, but deep listeners. And I think it’s a wonderful aspect because we’re getting so much information that they might not read.

And so I consider it a good but still insufficient alternative for the same reasons that involve comprehension monitoring on any screen. And that is with the audio, again, though you can go back to check yourself to monitor your comprehension, to remember the details, you don’t do it as easily. Or it’s very unlikely that you do it.

So even though I consider this as a positive, I don’t consider it a replacement. And indeed, your listener, the teacher, couldn’t be more correct. So many of our professors of high school and college are lamenting that their students are no longer willing or have the cognitive patience to read long-form text.

And there’s this common little aphorism, TLDR– Too Long, Didn’t Read. And the reality is that our professors are so worried that our students are really neglecting some of the 19th century– Melville– or 20th century– James. There are people who are writing me often and saying they are no longer having people coming to their seminars because of the density and length of books are off-putting.

And their students don’t have what I’m calling the “cognitive patience” to invest in retraining themselves to be able to read that. And there are implications not just for literature, but for referenda, for contracts, for dealing with the complexity of worlds that can’t be reduced to Twitter, our Twitter brains. We don’t want that for our young.

IRA FLATOW: Can you offer any remedy for this trend?

MARYANNE WOLF: Well, I certainly have been thinking a great deal about what would it take to develop deep-reading skills across every medium, because that’s really what we’re talking about. It’s cognitive choice to preserve what we know we want our next generation to have– at the same time, not just allowing, but propelling them to expand their 21st-century skills, their visual intelligence that goes so much beyond ours. So we want both.

And here’s where I tell your listeners. It is the perfect show in the world to say this. It is a hinge moment in which knowledge from science needs to be yoked with the designs from technology to be able to redress this and to create children who are really capable of biliterate and bidigital brains that have equal skills.

Now, you may know this, Ira, and your listeners wouldn’t. But I have proposed a way in which our children move from 0 to 10 on print and carefully use that kind of sensory-motor, concrete cognitive skills of children to learn deep reading over time with print and then have our teachers explicitly trained to teach deep-reading skills on the screen so that it’s not this willy-nilly assumption that you read the same on each mode. But rather, students are trained to ask, what is the purpose? What am I better at? Students don’t know what they’re better at.

IRA FLATOW: I better get a break in here. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m sorry. We have to take a break now.

MARYANNE WOLF: I know, Ira. This is so funny.

IRA FLATOW: But it’s an interesting point. So you’re saying that we could have a bilateral brain, as you call it. You could teach them how to read in print and then move them over to take the same skills with them when they read online. And that’s what you were just saying.

MARYANNE WOLF: Absolutely. But simultaneously, I want them developing at least from five years on the coding and programming skills. These are essential. And they give some of the same deep-reading cognitive skills that comes from print reading. I want those to come together. It’s not either/or.

IRA FLATOW: But you would have to retrain teachers to know how to do this.

MARYANNE WOLF: Yes, yes. And there’s really wonderful work in Europe and Israel and the beginnings here that we must have our teachers literally learn how to use the best of technology and the best of print. So we really need a whole generation of fresh professional development on this.

IRA FLATOW: Can parents do anything while they wait for the teachers?

MARYANNE WOLF: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. And parents have to actually be a good part of the story because it begins at zero to two, when a lot of parents are believing that the bells and whistles are good for their kids when they’re in fact not as good as they are in enriching language development. So before two, I want very little screen time for the kids. And never use it as a pacifier– the iPad as pacifier or as a caretaker– but to use it mindfully.

Catherine Steiner-Adair is a clinical psychologist who talks a lot about how we need to think about guidelines. Oh, also, the American Academy of Pediatricians, Barry Zuckerman– all of these people are really telling us how important it is to read and talk to our children in zero to five with only a gradual use of digital technology during that time.

IRA FLATOW: You can read more about this in Maryanne Wolf’s really interesting book, Reader, Come Home. You can check out an excerpt of her book on our website, sciencefriday.com/reader. Thank you, Maryanne, for taking time. It’s a fascinating conversation. Good luck to you.

MARYANNE WOLF: Absolutely for me. Thank you, Ira.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.