Writing The Fantastic In 2017

34:05 minutes

Science fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy—whatever the genre, authors of these books are in the business of creating great stories in other worlds that aren’t like our own.

Is building a new world different now than it was thirty years ago, before the internet, 3-D printing, or drones? And can a world that feels beyond reality teach us anything about ourselves or the time we’re living in?

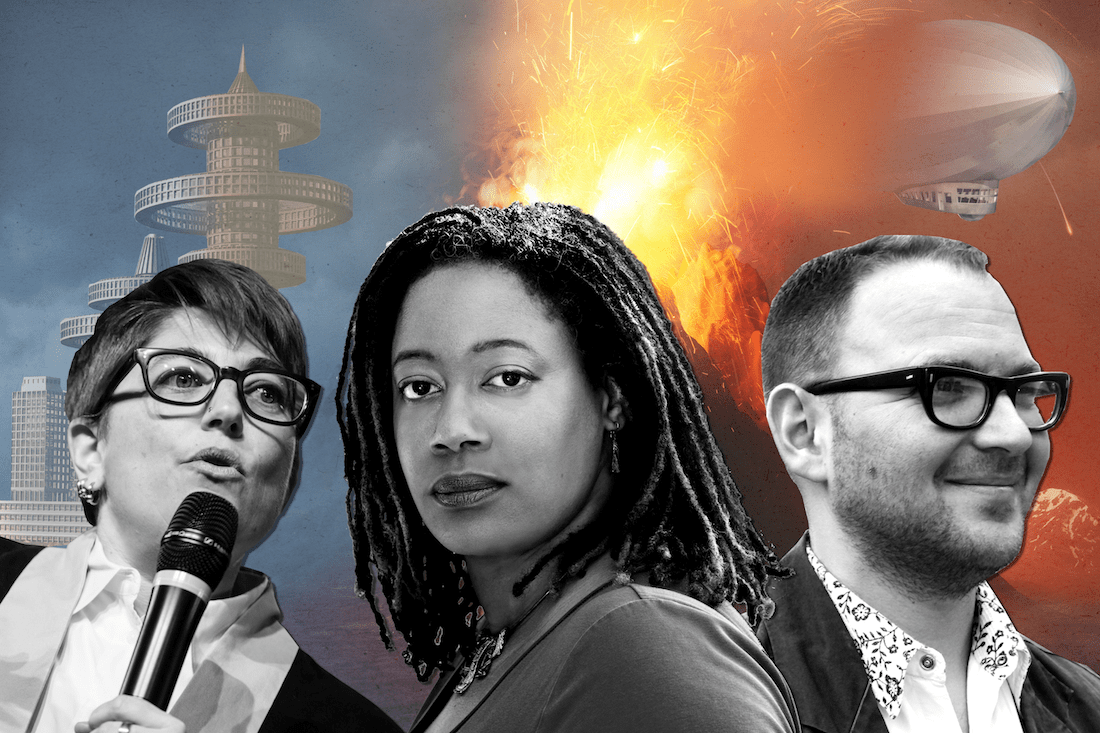

Authors Cory Doctorow, N.K. Jemisin, and Annalee Newitz all have new books out this year that venture to the near and far future, as well as to a planet torn apart by earthquakes. They join John Dankosky for a conversation about writing, reading, and inhabiting these worlds.

You can read excerpts of their latest books below:

Need more to read? Check out the Science Friday staff’s favorite other worlds in fiction.

N.K. Jemisin is a Hugo-winning bestselling speculative fiction writer and reviewer. Her most recent work is The Stone Sky (Orbit, 2017). She’s based in Brooklyn, New York.

Cory Doctorow is author of Walkaway (Tor, 2017). He’s based in Los Angeles, California.

Annalee Newitz is a science journalist and author based in San Francisco, California. They are author of Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age andThe Future of Another Timeline, and co-host of the podcast Our Opinions Are Correct.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is “Science Friday.” I’m John Dankosky. I grew up with science fiction. My father’s bookshelves were filled with the worlds of Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. They sat right next to the dark humor of Vonnegut and the fantasies of Tolkien.

I carefully read through all these classics, careful not to bend the pages as they took me to places far away and completely unreal– a distant planet or a high-tech future with robots or a not-so-distant future but with aliens. Now, some were, of course, completely dystopian visions. But what I remember was the sense of wonder and imagining something new and better.

That’s something that has not changed. Writers are still out there building us new worlds and riveting stories with just the power of their brains alone. We wanted to know, what is that process like? What kinds of decisions go into writing another planet, or our future planet ravaged by climate change? How do you decide which technology makes sense or how a robot might talk?

My next guests have some experience thinking about this. Cory Doctorow is editor at Boing Boing and author, most recently, of the novel Walkaway. NK Jemisin, whose latest book, The Stone Sky, wraps up a trilogy that’s already won two Hugo awards. And Annalee Newitz, tech culture editor at Ars Technica. Her first novel Autonomous just came out last month.

Annalee, NK, Cory, welcome to “Science Friday.” Thanks for being here.

NK JEMISIN: Thank you.

CORY DOCTOROW: Thank you so much.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Thanks for having us.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And if we– we want to hear from you, too. What makes other worlds believable to you, or plain enthralling? Our number is 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCI-TALK. You can always Tweet us @SciFri.

NK Jemisin, Nora, I’ll start with you. Maybe we can set the scene and talk about your most recent book. All three of you, of course, have new books out this year, but in your Broken Earth trilogy, it takes place in a world that’s upended by earthquakes and volcanoes and all the deadly side effects of unstable plate tectonics. What’s it like to live on this world?

NK JEMISIN: Not fun.

JOHN DANKOSKY: No, it doesn’t seem like it.

NK JEMISIN: Not fun at all, but it’s kind of a society of preppers, for lack of a better description. They have built their entire culture around the idea of trying to survive the apocalypse again and again and again. And there are forces at work in this world, possibly magic, possibly science, which allow some people to stop and start earthquakes and to possibly save or make worse the apocalypse, because why not?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Because why not. What’s the first germ of an idea that you had about this world that you created? I mean, what was the origin of this?

NK JEMISIN: I had a dream that I tell people about, where basically, a woman was walking towards me who was very, very angry with me. I didn’t know why, because it was a dream. And she had a mountain floating behind her that she was planning to throw at me. And I knew without her saying anything that she was going to throw a mountain at me. And I needed to know why this woman was so angry that she had literally picked up a mountain with her mind and how that happened, so the world was me trying to make sense of my subconscious brain having fits.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I love the idea that it actually comes from a dream. Well, let’s turn to Cory Doctorow. Walkaway takes us to a future Earth where we can 3D print anything we want. Maybe people can live forever. But it sounds great, but maybe not so great. Tell us about this world and how you created it.

CORY DOCTOROW: Sure, so this is about this contradiction that comes up when we use our social and technological infrastructure to allow us to make more things better. We can make things that have less material. We can have more material abundance, but without any sense that we have any shared duty to one another or any reason to care about what happens to someone else, which ends up with kind of catastrophic environmental blight and out of control runaway crises and a crisis in the economy where most of the people just are no longer seen as necessary to the small number of people who, through something that they’re quite sure is a meritocratic system, have accumulated almost all the wealth there is.

And against this backdrop, there’s this group of people who say, you know, material abundance is ours if we want it, and they just walk away. They walk away into these blighted zones. They use stolen software from the UN High Commission on Refugees to direct these clouds of drones to scour the ruins for things that they can use to build giant luxury resorts that are self-maintaining, and then anyone can live in a kind of fully-automated luxury communism.

And they lead these very [INAUDIBLE] lives. And every now and again, some rich weirdo will get the idea that that bit of blighted land and all that garbage belongs to him. And rather than fighting back, they move somewhere else, because, you know, all garbage and all blighted land is fungible.

And that’s all ticking along very well until this moment when the scientists who have been employed by the elites figure out something that approximates immortality. And rather than give it to them and speciate the human race into, you know, infinitely prolonged supermen and us mayflies receding in their rearview mirrors, they bring the fire of the gods to everyone else so that everyone can be immortal. And once the very rich people realize they’re going to have to share the rest of the world with us forever, that’s when the hellfire missiles come out.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, so those are two different visions. Our third vision, this time of the future, patent law more important than other human rights. Pharmaceutical companies protecting their profits at the cost of human lives. The Arctic, of course, has melted. What else can you tell us about your world, Annalee?

ANNALEE NEWITZ: So my world is– it’s about 125 years in the future. And we follow two main characters. One is a pharmaceutical pirate named Jack, of course, because she’s a pirate. And she has– she’s a scientist, but she gets really disillusioned with her ability to help people, because drugs cost so much money. And she wants to develop medicines, but she can’t get them to anyone but rich people.

So she has decided to go rogue, and she is pirating drugs from pharmaceutical companies and giving them to the poor or selling them at very low cost. And she makes a mistake. And so she kind of gets on the radar of one of these companies whose drugs she’s been pirating. And through a series of incredibly corrupt connections, this company is able to kind of strong-arm an economic coalition to send a couple of agents after her to basically eliminate her. We’re not sure entirely if they’re going to kill her, but probably.

And the agents are a human and a robot, who has just been freshly made, and the robot’s name is Paladin. And we follow Paladin’s kind of coming of age as he or she, depending on what you prefer, chooses– tries to choose a path in life while also being under the control of the programming of the people that own him.

And one of the big changes in this future world is that slavery has become a cornerstone of the global economy. And so robots are enslaved, but also, corporations, through a series of legal maneuverings, have set things up so that humans can also become enslaved. They can choose to become indentured servants, which– indentured servitude is just a nice term for slavery, basically. So the characters are grappling with both intellectual property, the kind of patents that are put onto these medicines, but also human property, people becoming property.

JOHN DANKOSKY: If NK’s world is forged in a dream, this sounds like it could be taken from bits and pieces of, like, what’s in the newspaper right now. Is that where you are finding your inspiration, I mean, from current events and what’s happening right in this moment?

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Well, this novel was actually born in a seismology lab. I’m a science journalist. And I visit a lot of labs. And a lot of the action in this novel does take place in labs.

And I was visiting this lab where scientists were using giant robotic arms to crush a house in order to figure out how earthquakes work. And I started thinking about what it would feel like to have one of those actuators that they were using as an arm and what kinds of feelings I would get. And so that’s where I kind of met Paladin, was– Paladin’s first scene is he’s climbing a sand dune, and he has sand in his actuators, and he’s feeling pain for the first time. And so, it came out of, you know, lab work and pain.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And wanting to create earthquakes, I guess.

NK JEMISIN: That’s so cool. I have to visit that lab.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: It is a great lab.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, NK, talk a bit about how you build a world and how difficult it is compared to building a story, because as a novelist, you want to flesh out three-dimensional characters, and you want to have a plotline that people can follow and grapple onto, but you’re also constructing around them all of these other things. Tell me about the difficulties or challenges of building a world versus building a story.

NK JEMISIN: Well, I mean, you know, I do a four-hour workshop on this, so I’m going to have to try and hold back a little bit. But I mean, so with the worldbuilding, what I basically do is we start at the macro level. You know, something– in science fiction and fantasy, you can start with something as basic as the laws of physics. But then you’ve got to figure out what kind of planet you’re working with, how that climate and the structure of that planet influences the culture that develops.

You know, of course, it’s science fiction. You can also talk about the species that develops, but– and in this particular case, since I was dealing with a society that was responding again and again to these immense extinction-level events, you know, what I was trying to get at is not only how do people react to that constant pressure, but how do they react to the fact that they’ve got a group of people who could help them?

And you know, one of the things I didn’t mention in my summary of it is that these people are effectively enslaved, as well. They are highly stigmatized, because they can both stop and start earthquakes, and sometimes they can’t control the starting an earthquake. So people sort of talk about them as if they are necessary but frightening, which they are.

And so the only way that they’re able to kind of have a legitimate life is if they go into a kind of evil Hogwarts, where they are trained to use their power and made into tools for the state. And it’s slavery as well, by another name. But so how do these people balance the need to survive against the need to depend on people they despise in order to do so?

So the worldbuilding, once you’ve gotten past that macro stage, then you start looking into the microcosms of how do societies work? And you know, I’m a psychologist in my day job life, or I was when I had a day job. And so you’re looking at things like sociology and group dynamics and so forth, and roles, power dynamics. How do people behave under pressure?

And it’s no different from looking at other forms of science when you’re applying that to science fiction. You know, there’s a tendency to treat the soft sciences as if they’re not important. They actually are. So I had to research both sociology and seismology, so yeah.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Cory, talk about your process. As you create a world, what are the things you’re thinking about and that you need to grapple with as you’re creating a world for your characters to inhabit?

CORY DOCTOROW: Well, you know, I think we have this, like, crisis of imagination when we try to think about the future. We either try to be optimistic or pessimistic, like either things will work out really well or they’ll work out really badly. And I don’t think that’s actually how stuff goes. First of all, I think that anyone who tries to predict the future is– that that’s more or less the most pessimistic thing you can do, because if the future will arrive no matter what you do, if it’s predictable, then, like, there’s no reason to get out of bed.

So I think that the future is contestable. It depends on what we do. And if the future is contestable, then what matters is not, like, will the future be better or worse, but what can we do to make the future more better and less worse? And we have this crisis of imagination, I think, that starts maybe with Margaret Thatcher declaring there is no alternative to the system that she was building along with Reagan and other leaders in the ’80s, where markets became the arbiters of our moral character and the thing that determined whether you’re doing something good or bad. And we find it really hard to imagine anything else.

And so what I did was I sat down and said, if I was general arranging troops on the world stage to make things more better and less worse, what moves would I make? Not like, will the world be better or worse? But what moves would I make and what counter-moves would people make? What could that look like, the push and the pushback? Because we don’t solve problems. We just fight problems, kind of forever, you know?

They broke up the phone companies in, like, 1982. That didn’t end phone monopolism. Like, AT&T executives didn’t all go move to an ashram and become Zen Buddhists. They just, you know, hung around like Voldemort on the back of other people’s heads until they could reassemble themselves into this giant, nation-spanning, horrific monopoly, right?

That’s not a problem that you solve and walk away from. It’s a fight that we join forever. And so that’s the thing that I was looking for, is, like, what does that long fight look like at different stages?

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky. This is “Science Friday” from PRI, Public Radio International. And we’re talking with an all-star panel of science fiction and fantasy writers, Cory Doctorow, NK Jemisin, and Annalee Newitz. We’ll take some of your phone calls in a bit at 844-724-8255.

Annalee, what did you have to learn about science? Obviously, you have a science background, but what did you have to learn to put into this book so that you had a believable world?

ANNALEE NEWITZ: I had to do a lot of research. And I started out treating this book a lot like the way I would treat writing a science article. And I contacted roboticists. I wanted to know what a robot would be made of, what its muscles would look like.

Could I give it wings? The answer is yes. Wings.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Of course.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Wings and lasers, of course. And I talked to, actually, a number of neuroscientists, because that’s an area of science that I wasn’t very familiar with, and my characters are grappling with a drug that’s basically changing the structure of people– you know, changing the sort of neural networks in people’s minds, and not in any way that is magical, but I wanted to know really fundamental things, like, if you’re looking through a microscope, can you see receptors growing on neurons in real time? It turns out yeah, you can.

And so I wanted to have my characters doing things in labs that felt realistic. I talked to synthetic biologists, because some of my characters are synthetic biologists. And they gave me some great ideas for some super evil, creepy things to do in the book. There’s a character who grows plants out of her head, and I wanted to know about how that would work.

But also, as Nora was saying, you know, it’s not just about what we think of as the hard sciences, because one of the big questions for me was how do I make it believable that people would actually choose to become indentured servants? Like, what would make you want to do that? And so I sat down with an economist, and I said, look, what do we need to change if we’re doing a thought experiment to make this an appealing option, because there’s a regulatory agency in my future, the International Property Coalition, that refers to this as the human right to indenture, because it’s our right to choose to become slaves.

And the economist pointed out to me that, you know, we have a lot of rights now in the West that we don’t think of as rights, like the right to work in a certain place or live in a certain place. And what if you had to pay to do that? Like, what if you had to pay to work in New York? What if you had to pay to get any kind of emergency services in New York? And so if you don’t have the money to do that, then you have to become indentured, because otherwise you can’t live or work anywhere.

And so that was what I did, was I took away some rights from my characters. And suddenly, they all magically wanted to be slaves.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So yeah, so talking to economists. As you said before, Nora, the soft science is very important, right?

NK JEMISIN: Well, it’s all science, at the end of the day.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s all science in one way or the other. I have to ask you– we just have a quick minute, but there’s a– you use magic with science in it, and that’s a difficult thing to understand. I mean– well, maybe we should take a break, because I want to linger more on this, because this idea of developing magic that has elements of science in it is actually a pretty important part of what you do.

When we come back, we’re also going to take some phone calls at 844-724-8255 as we talk with Annalee Newitz and NK Jemison and Cory Doctorow about writing other worlds. You can also Tweet us @SciFri.

This is “Science Friday.” I’m John Dankosky, and we’re digging deep into the fantastical worlds of science fiction and fantasy, how these worlds are made and why we love them. We’re joined by a panel of authors for whom building worlds is their stock and trade.

We’re joined by Annalee Newitz, who’s author of Autonomous, Cory Doctorow, author most recently of Walkaway, and NK Jemisin, author of the Broken Earth trilogy. The third book, just released, is called The Stone Sky. Before our break, I was going to ask you about– your worlds feature magic and fantasy in a way that some science fiction doesn’t. I want you to talk about how much you believe that magic can take us so far, and it needs to interact with science. I mean, does magic need to be believable to actually work?

NK JEMISIN: No, I don’t think it has to be. But in this particular case, I really kind of felt like playing with Clarke’s law, which is any sufficiently advanced magic– I’m sorry, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. And there’s a fantasy corollary of that, which is any sufficiently systematized magic is indistinguishable from science. And I really was just kind of like, well, that just begs to be, you know, treated in a very blurry fashion.

And so I wrote magic, and I systematized it, and, you know, I didn’t use the word magic throughout the first book of the series. I tossed in magic just on a lark in the second book, and then continued to treat it like science. And it’s confused people a lot, and they’re really unhappy about that. And I’m enjoying it so much.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: I wanted to add something, because I think part of what’s so great about the Broken Earth trilogy is that we see how certain characters think of the technologies and think of the science as magic because they’ve partly been hoodwinked by the ruling classes, who don’t want them to really understand the science that’s being used. And that felt to me incredibly believable.

And it kind of describes our relationship with a lot of technology and science now, where people kind of take for granted that it will work, but don’t really know how. And that’s why they can kind of demonize scientists, because they don’t realize how much science underlies their everyday life. And so I thought that was a particularly fun part. I can see why it pissed people off, though.

NK JEMISIN: Or they don’t know the costs involved. And you know, they start using the science without realizing that there’s no magic solution to what those costs are going to be.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to get to a phone call. Dave is calling from Milwaukee. Hi there, Dave, go ahead.

DAVE: Hey. Hi, everybody. I have to say that I need to pinch myself. I can’t believe I’m on “Science Friday.”

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, I’m glad you called Dave.

DAVE: I’m sort of freaking out. And this is a great show. It’s right up my alley. And the question is, there’s a lot of science fiction that revolves around dystopian, and I love that science fiction. I love dystopian and thinking about what life would be like when the bad powers take over and aliens and blah blah blah.

But everyone probably on this phone, or on this program, loves Gene Roddenberry. And when I think about Star Trek, and I approach it from a sociopolitical perspective, I’m wondering what you guys think. Will we ever evolve as a species to what I call a Star Trek world where there’s no sexism, there’s no racism? [? In ?] fact, they don’t talk about it, but if you can replicate anything, you don’t need money, so it’s probably a cashless future. It seems a utopian future that I would love to get to someday, and I’m curious to see what you guys think.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Dave, thanks so much for the great question. Corey, you want to tackle Dave’s question?

CORY DOCTOROW: Yeah, it’s, you know, kind of a favorite subject of mine. I think that it is not dystopian or pessimistic to imagine that the systems that we have will fall apart or stop working, right? Engineers who design systems on the assumption that nothing will ever go wrong do not make well-functioning machines. They build the Titanic.

And so it is not dystopian to imagine a collapse. And so the furniture of dystopia, right, the kind of awesome, Mad Max aesthetic of dystopia, is not a pessimistic thing. What is pessimistic is the idea that when the lights go out, your neighbors will come over and eat you? Right?

And it’s not just pessimistic. It’s kind of, you know, unrealistic, right? The idea that you and all the people you’re friends with are basically decent people, but everyone else is like a monster in waiting. It’s like– statistically, it’s so unlikely that you just happen to luck into only knowing the nice people. It’s much more likely that everyone’s kind of a flawed vessel.

And so for me, I think you can write optimistic disaster stories, stories where the lights go out, and instead of your neighbor coming over with a shotgun, they come over with a covered dish. Right? Which is like– it jives with what actually happens. You know, Rebecca Solnit, the wonderful historian and writer, wrote this great book called Paradise Built In Hell, where she uses first-person accounts that are contemporaneous with disasters from the last two centuries to talk about how, you know, that disaster moment is a moment when the background hum of petty grievance stops and in the sudden ringing silence, you realize that you have more in common with your neighbor, who you’ve been fighting with about where they put their sprinklers, than you have a difference. And you go and start digging them out of the rubble.

And I love that story, because that’s a story where all the conflict doesn’t come from easy conflict of trying to vanquish people you disagree with. It comes with the much harder conflict of trying to get your own way among people who you like or even love but who fundamentally think that something different should be done, right? Like, winning a Christmas dinner table argument is not a happy experience, right? Vanquishing the people you love will make you miserable.

And so the stakes are much higher, I think. It’s kind of lazy to just go with these easy dystopias.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I would love your thoughts on this, Annalee.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Well, I think that the thing– Star Trek is an interesting example, because we keep kind of returning to the Star Trek narrative, and we have been for over 50 years. And I’ve been very interested to watch the new Star Trek series Discovery, which actually explores all the ways in which this is a future that’s really flawed, and it is full of things like racism and sexism and, you know, turning science into a wing of the military-industrial complex and all the other kind of bad things that we think of. And I think that one of the things that we get confused about a lot when we think about the future is this idea that somehow because we are becoming more technologically adept or because we’re developing really advanced technologies like replicators, that that will somehow parallel another kind of social advance and that we will become closer and closer and closer to, like, a perfect democracy where everyone is equal because we are coming closer and closer to lightspeed or because we’re getting better computers or because we have AI. And I think that’s not how it works. And that’s the difference between social progress and technological progress, is that they’re not the same.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Some of the new research actually shows, I mean, our smartphones might be making us less socially conscious. I mean, we might be worse people because of the technology in some shorthand way. And I’m wondering if that’s a piece of this, too, that you have to look at the technology as something that can take us somewhere that’s never gone before, but it can have, obviously, these consequences, even on a day to day basis.

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Well, until we have technology that has sort of human-equivalent intelligence, we can’t say that technology does anything, right? It’s all about how we use the technology. There’s always another human being behind that technology.

And so what I think we have to consider is that human progress toward this kind of egalitarian goal, throughout history, regardless of whether they had smartphones or whether they had just, like, invented pottery and that was like their most badass invention at that time– like during the Neolithic, that was a pretty big deal– people have had these sort of fits and starts. Like, we’ve had– we’ve approached more democratic societies and then we’ve fallen back into autocracy or we’ve fallen into oligarchy. And I say fallen only because, you know, if we think of egalitarianism as an ideal, this is a kind of falling away.

It doesn’t mean that we go backward in time, because in fact, we can be zooming into the future. We can have spaceships and authoritarian dictatorships. And I think that’s one of the things that’s interesting about the future is that we can sort of imagine not dystopia, not utopia, but just “topia,” you know? It’ll be– there’ll be a bit of the good, a bit of the bad. You know, like, OK, yeah, we’ll have better earthquake control, maybe, but we’ll still have people who are social outcasts.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’d love your thoughts, Nora, on that sort of utopia, dystopia divide.

NK JEMISIN: Well, I mean, to kind of get to your question about Star Trek, one of the biggest sort of fantasies in science fiction is the idea that we can get to this utopian future without any work, that the technology alone is enough to get us there and that we don’t have to actually work on each other or ourselves. And that’s been a kind of long time failing of science fiction and fantasy in that sense.

And you know, I really do believe that– you know, I agree a lot with what Cory was saying as far as people in disasters look out for each other. This is one of the things that I was figuring out when I was researching preppers and how people survive disasters. People come together. You see more community behavior and people actually looking out for each other and so forth. You don’t see anything like Mad Max.

And I don’t believe that we would see something like that. I think there’s a certain weird fantasy of rugged individualism and a fantasy of bigotry, that those people over there are going to come and eat you. But the truth of the matter is that these are irrational things, and bigotry is fundamentally irrational. There’s no way to kind of reason it away.

And there are certain specific things that need to be done to address those futures without racism and sexism, and they’re not technological things. They’re all people-based things. And you know, until we kind of acknowledge the fact that working on the people is part of the way that we get to the future as much as working on the tech, we’re not going to get very far. The technology will just continue to be in service to our same old base desires and base behavior.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m wondering, Cory. We mentioned Star Trek but we also have Blade Runner coming out right now, a future that was thought of some time ago that’s now basically the present. And now we skip forward another 30 years. It’s clearly a dystopia. I’m wondering about the world that we live in right now and in what elements of 2017 you think are especially relevant for people writing a future world?

CORY DOCTOROW: That’s a really interesting question. You know, I think maybe my approach is a little different from the one that’s kind of implied there. I think of writing about the future not as predictive but as– maybe as diagnostic? So like, if you go to the doctor, and she swabs your throat and then puts it on a petri dish for three days and then looks at it under the glass, she’s not trying to figure out an accurate model of your body. She’s trying to make this usefully inaccurate model of your body where one fact about you is the totalizing force in this model of your body in the petri dish.

And I think in science fiction, we often reach into the world and pluck out one technology, you know, algorithmic ascription of guilt, like the 1,000-page no-fly list or, you know, the use of cryptography for good and bad by bad actors and good actors and insurgents of all kinds. And we make that, like, the one fact about our future world, not to predict it but to try and kind of surface the stuff that’s latent in our world today, you know, to try and predict the present, because although the future is unknowable, the present is the moment at which the past is becoming the future, so the better you understand the present, the more prepared you are for that future.

JOHN DANKOSKY: First of all, I want to say this is “Science Friday.” I’m John Dankosky. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

I’m wondering a little bit about the worlds that you create, NK. And we’ve talked about dystopias and the current state of the world. When you think about, is a world worth saving, do you have to create a different world to really test that question? Because it’s so fraught when you think about whether or not our own world, the place that we live, is worth saving.

NK JEMISIN: I think that depends on who you ask. You know, it’s a thing that I say a lot is just that dystopia is relative. Depending on who you’re talking to in our society, we are a dystopia right now. Depending on which part of the world that you choose to focus on, we are a dystopia right now.

And so, you know, the idea that– basically, in the books, what I was exploring was the fact that this is a society which at varying times has been as close to utopian as it can get. And what you see mostly in The Stone Sky, you know, the– I don’t want to spoil things, but you know, one of the points in the past where they achieved really high technology and a what we called solar punk lifestyle, which is buildings with plants and things like that, they had achieved a really fantastic lifestyle, and yet at the same time, there was a holocaust in their immediate past. And they were actually planning to complete that over the course of the whole story.

And so there’s a number of elements in there that kind of show that even though you can have this really advanced society, you’ve still ultimately got to deal with the ugly, brutal, primitive baggage of the days back when bigotry and so forth were talked about and were sort of fought. And unfortunately, this is a world where the attempt to fight bigotry failed. And so they moved on with their technology, and their society was rotten at the core. And I think this is one of the things that potentially awaits us if we’re not careful.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Annalee, what do you hope that readers take away from the worlds that you’re creating? What do you think that it gives them as they read the work?

ANNALEE NEWITZ: I really do hope that they come away with a sense of hope, actually, because the world that I’ve created– kind of as Corey was talking about, this isn’t really about predicting the future. It’s about sort of talking about the present.

And my characters are all survivors. They’ve been through incredibly hellish experiences. They’ve fought for what they believed in and failed. They’ve screwed up. They’ve been enslaved.

They’ve had their minds controlled by corporations. They’ve become addicted to horrible drugs. But they make it, and they make it by forging alliances with each other. The way that they survive isn’t by becoming rugged individuals who go off and, like, into the sunset.

It’s by falling in love with each other. It’s by forming a band of people who can work together to try to make things slightly better than they have been before.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I just have a little bit of time left, only a couple minutes, so I want to quickly ask you– and I’ll start with you, Annalee– who else is creating great worlds? Are there anybody that you should be putting on a reading list right now?

ANNALEE NEWITZ: Sure, I mean, right now, I’m very excited about the work of Ann Leckie. She’s another great writer who’s won a bunch of awards. She has a new book out called Provenance that I really like.

I’m in the middle of reading JY Young’s novella The Red Threads of Fortune, which is fantastic. And it’s a companion piece with another novella, so if you like it, you can get the other one. And she also– or they also combine magic and technology really nicely. So Red Threads of Fortune is a great– I would check out their book.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Cory Doctorow, very quickly, maybe a recommendation for our listeners?

CORY DOCTOROW: Sure. Last couple of weeks have seen some really good books published. Naomi Alderman’s The Power, which is kind of The Handmaid’s Tale with a gender swap. It’s outstanding. It’s been out in the UK for a while and has gotten amazing reviews.

William Gibson’s graphic novel Archangel that he did with– oh, gosh, I’ve forgotten the guy’s name, but William Gibson’s Archangel, his new graphic novel. Outstanding. And then Landscape With Invisible Hand, a wonderful middle grades book by MT Anderson, who wrote Feed. It’s a sarcastic, great novel.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’ve got to get to Nora. One quick recommendation?

NK JEMISIN: I actually can’t give any because I’m a reviewer. Sorry.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s perfect for our time, though. I appreciate it.

NK JEMISIN: All right.

JOHN DANKOSKY: NK Jemisin–

NK JEMISIN: Sure.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Thank you so much for joining us. Thanks so much to Cory Doctorow and Annalee Newitz. Have a good weekend, everyone. Enjoy some good books.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.