Who Killed The Passenger Pigeon?

6:22 minutes

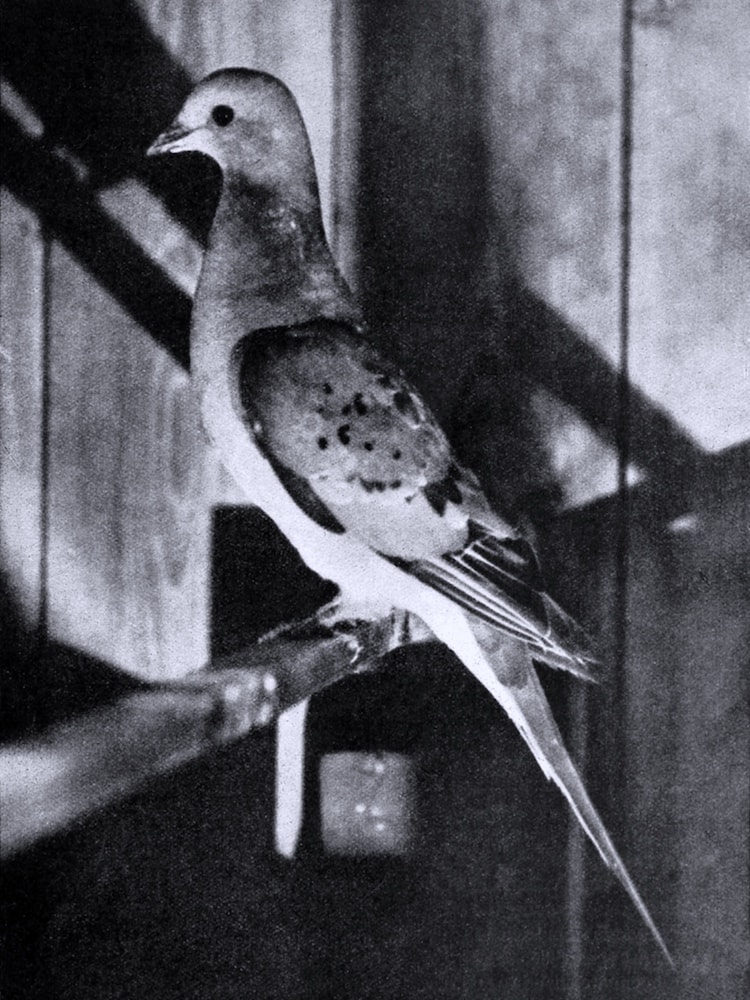

After humans with guns began hunting them for food and sport, the bird quickly went extinct, leaving behind a scientific mystery: Why didn’t small populations persist?

A new DNA analysis, published this week in Science, offers one possible answer: A surprisingly low level of genetic diversity. Beth Shapiro, a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz and co-author on the new research, explains why the passenger pigeon might hold lessons for other contemporary animals with seemingly large, stable populations.

Beth Shapiro is author of How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-extinction (Princeton University Press, 2015) and associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz in Santa Cruz, California.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of birds, the passenger pigeon was another bird that once ruled North America. There were as many as three to five billion– that’s with a B– at their peak, three to five billion. Historical accounts tell stories of flocks so large, they blocked the sun for hours at a time. And then hunters with guns showed up shooting them for food and sport, and by 1914, there was only one left, and she died in the Cincinnati Zoo.

So how did this happen to an animal with such a large, stable population? New research looking at passenger pigeon genes might offer a clue. Turns out that their large numbers, a helpful adaptation, might also have left them vulnerable to human hunting. Here to explain more is Beth Shapiro, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. She’s also a co-author on this new research. Welcome to Science Friday.

BETH SHAPIRO: Hi, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: So what was the original theory behind why the passenger pigeons went extinct so quickly?

BETH SHAPIRO: Oh, I think for a long time, we’ve known that this was pretty much our fault. We were incredibly successful and skilled hunters of passenger pigeons. But a few years ago, a study was published that suggested that their populations actually fluctuated quite considerably over time, and that this might have meant that they were already on a decline when humans turned up and started shooting them. And we found that this is, in fact, not true, that their populations had been extremely large and stable for at least the last several tens of thousands of years, even during the last ice age.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, this is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, talking about the disappearance of the pigeons. And now we know that it was because of– why? What did them in?

BETH SHAPIRO: Yeah, well, it was definitely us. We were doing some crazy, industrial-scale murder of these animals. Their populations were large and stable, and this meant that they were able to adapt really, really efficiently and really quickly to living in these large populations. But we came in there, and over the course of just several decades, we took them from billions of individuals to really rather few.

And I’ve always been curious why smaller populations of these birds hadn’t survived in some refugial forest stand somewhere. But it seems that maybe because they were so big for such a long time, they just became incredibly well adapted to living in these large populations. Had our hunting been less efficient, had we killed them more slowly, perhaps they would have had a chance to adapt to this new surrounding, this new situation of being in tiny populations. But they certainly didn’t.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about– So there’s no reason why they could not have survived in small colonies away from the hunters?

BETH SHAPIRO: Well, what we think is that because they were so, so strikingly well adapted to living in large populations. These would be things like, if you live in a large population, you probably don’t have to work so hard to find a mate. Or you don’t have to worry so much about predation, or about finding food, or thinking about where the next giant forest stand full of nuts might be.

But once you’re in a very small population, this is all of a sudden something you have to be quite good at. And if that ability had been lost over the course of tens of thousands of years of living in large populations, it would have been tough for them to survive as a tiny population.

IRA FLATOW: How could a bird that numerous– you know, it’s just– I’m just keep asking you, because it’s kind of hard to understand. Are there contemporary species that these lessons might also apply to, that we’re going to lose them if we keep hunting them?

BETH SHAPIRO: I certainly think that this is something that we should think about, that comes out of these types of analyzes. And I’m often asked this. I mean, we work on species that are extinct, why not focus on things that are alive? But I think there are things that we can learn from the past, that we can then apply to making more informed decisions today. And I think what the passenger pigeon story tells us is that we often think of things that are in large populations as being not particularly vulnerable to extinction. But perhaps that’s not true. And perhaps when we’re thinking about whether a species is in danger of becoming extinct, we really need to think more holistically, start to consider the entire history of adaptation of that species.

I don’t know if there are any species alive today that are particularly vulnerable because of this, but something that comes to mind, to me, are fisheries, for example. We know that fisheries have been very large. They tend to be large populations that are connected to each other. And when we think about restoring them, we often don’t think about restoring them to these formerly enormous populations, but somehow being able to achieve smaller populations, potentially even isolated populations. But this may not be what these species really need to be able to come back.

IRA FLATOW: One quick last question, because whenever we talk about lost species, we talk about woolly mammoths and things like that. People want to get the DNA, right? And bringing them back, would that be possible with a passenger pigeon?

BETH SHAPIRO: Well, there’s a lot more to talk about if we want to talk about resurrecting passenger pigeons. There are many, many technical hurdles that are still in the way there. We do have the genome sequence now, and we have a genome sequence from the closest living relative, which is the band tailed pigeon. But we still don’t really know how to do genome editing and engineering in birds. And that’s because we can’t clone birds, much like we can clone mammals, like Dolly the sheep. This is not yet somehow we can do with birds.

IRA FLATOW: This is a whole other conversation We’ll have to hold it for another time. This is fascinating. I didn’t know that, didn’t realize that. I’m going to have to say goodbye, because we’ve run out of time.

BETH SHAPIRO: Let’s talk about it another time.

IRA FLATOW: We will. Doctor Shapiro, thank you for taking time to be with us today. Beth Shapiro, Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of California, at Santa Cruz.

One last thing before we go. The Leonid meteor showers peaks this weekend. If you want to see them, get out there tonight. Wishing you– and tomorrow night, I think, too. Wishing you clear skies tonight and tomorrow. B.J. Leiderman composed our theme music. And we had help today from all the folks here at Louisville Public Media, WFPL, and Michael Schooler, and his whole crowd here. Thank you all for your hospitality.

If you missed any part of our program, you want to hear it again, subscribe to our podcast. And we’re everywhere these days, Amazon Echo, Google Home. Every day now is Science Friday, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. Have a great weekend. I’m Ira Flatow in Louisville.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.