What Will It Take To Have Seamless Transportation?

17:17 minutes

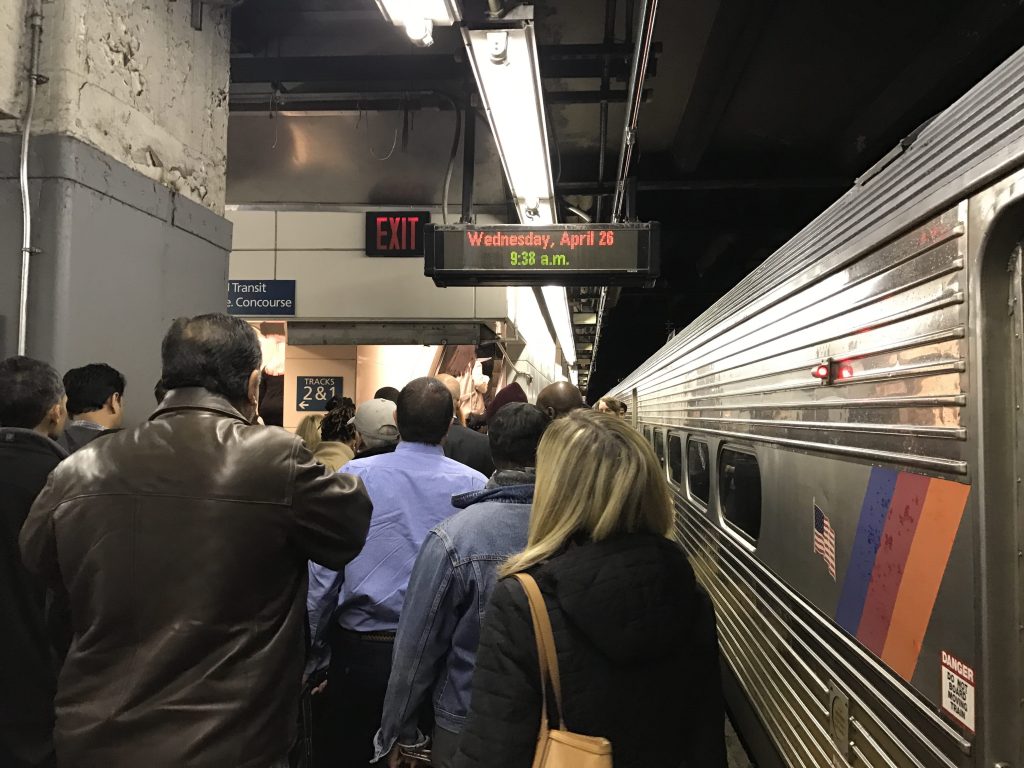

It’s been a rough week for anyone who relies on New York City’s Penn Station, which has seen a rash of track closures, maintenance delays, and technical problems over the last month, with more slowed commutes likely ahead. Add to all of that the perennial problems of Washington, D.C.’s Metro and a highway overpass collapse on Atlanta’s Interstate 85 last month, and you have a large number of frustrated commuters in three major cities alone. Just in March, the American Society of Civil Engineers gave the whole of American infrastructure a D+ rating, with transit rating only a D-, and bridges coming in at a C+.

[Can science untangle our transit maps?]

With the president pledging an investment of up to $1 trillion in infrastructure, including roads and bridges, we ask where that money might have a positive impact on the daily struggle to get to work. Martin Wachs, professor emeritus of city and regional planning at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs, discusses the matter with Andrew Herrmann, past president of the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Also, WABE reporter Lisa George gives an on-the-ground look at how a single stretch of closed highway can affect the daily lives of Atlanta residents.

Lisa George is a reporter at WABE in Atlanta, Georgia.

Andrew Herrmann is Past President of the American Society of Civil Engineers and a partner emeritus at Hardesty & Hanover in Boston, Massachusetts.

Martin Wachs is a Distinguished Professor Emeritus of City & Regional Planning and Civil & Environmental Engineering at the University of California-Los Angeles in Los Angeles, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

How has your commute been lately? Is it smooth driving, an easy, busy ride, a seamless train journey? Well in New York and other places it’s been a little rough from ongoing signal problems and maintenance delays, to a power outage that snarled a half a dozen subway lines last month, to the growing nightmare that is called Penn Station.

The New Jersey Transit Authority will even write you a note for your boss if a delay makes you late. I was stuck on a train the other day. Delayed because of an electrical issue. Got to Grand Central where not one, but two escalators were on the fritz. And they were the up escalators, of course.

But it’s not just we New Yorkers. One line of the Metro in Washington DC shut down yesterday morning after smoke was spotted in a tunnel. Not an unusual occurrence, I’m told. Excuse me. Atlanta residents know what I’m talking about. At the beginning of the month an overpass on Interstate 85, one of the main routes into downtown, it caught fire and collapsed. The repairs are due in another six weeks.

Lisa George, a reporter at WABE in Atlanta, walked to the scene of the disaster when it first happened. Lisa, welcome to Science Friday.

LISA GEORGE: Thanks so much. Happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: You walked to it. It was that close?

LISA GEORGE: It was. As the crow flies about a quarter mile between our station and where 350 feet of highway went down.

IRA FLATOW: So how does a fire take down a whole highway overpass?

LISA GEORGE: Well, you know, that’s still a matter of debate. What was stored under the highway were two to three dozen giant, wooden spools that had, what’s known as, high density plastic conduit under it. Now, how that fire started is a legal matter at this point. The allegation is that someone set fire to a chair or a sofa that was on top of a shopping cart under this underpass and that it smoldered till it caught the conduit and the spools on fire. So it was really the heat that brought the highway down. Not the fire itself.

IRA FLATOW: So Atlanta wasn’t exactly an easy place to get around before this.

LISA GEORGE: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: And now you have the fire, and the bridge is out.

LISA GEORGE: Yeah. And by the way, I-85– this is just north of downtown Atlanta where this happened. Just before I-85 merges with I-75. So we’re talking a major route in and out of downtown Atlanta with more than 200,000 cars going across this overpass everyday.

IRA FLATOW: So how people are adapting? Are they just spending more time commuting? Are they staying home? Are they telecommuting?

LISA GEORGE: All of those things. Public transit ridership is up an average of more than 10%. In the first couple of days after this happened it was up 25%. And many businesses, including our own here at WABE in Atlanta, have shifted their working hours. Or, in the case of the newsroom, it’s now if you don’t have to be in the newsroom then work from home, if you can.

And in the first few weeks school systems and even municipal governments switched their working hours for a while.

IRA FLATOW: So how is this dealing out in the politics of the city? Are people saying, you know the city should have been better prepared for this kind of incident.

LISA GEORGE: Well, actually everybody’s got a pretty good sense of humor about it. I mean, we have traffic problems here all the time anyway. So everybody’s pretty prepared to spend an extra half hour in the car or to find a new route. One of the few problems has been that the surface streets in the Midtown and Morningside areas of Atlanta, the residential streets, they’re getting a little clogged up with people using their various traffic apps and finding new ways through. And those people who are posting signs asking for no thru traffic to come through.

IRA FLATOW: So you’ll just have to grin and bear it, as they say, until the bridge gets fixed.

LISA GEORGE: Exactly. And they’re saying June 15 or before. And there’s more than $3 million on the table for the contractor if it finishes early.

IRA FLATOW: Well. We’ll just have to wait and see what happens. Thank you, Lisa. Lisa George, reporter for WABE in Atlanta. Walked to the scene of the disaster when it was first happening. Thanks again for taking time to be with us today.

LISA GEORGE: My pleasure. You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: President Trump has pledged a trillion dollars, he says, to repair crumbling infrastructure. No details on that. Congress has yet to weigh in. But engineers have been studying the decaying landscape for decades. And that’s what we’re going to talk about with some engineers. Martin Wachs is professor emeritus of city and regional planning and civil and environmental engineering at UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs in Los Angeles.

Andrew Hermann is a partner emeritus at engineering firm Hardesty & Hanover, past president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. They both join us from Boston. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARTIN WACHS: Thank you very much. It’s a pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: I imagine you were listening in on that, Andrew. Where do the troubles in Atlanta fit into the general state of our transportation infrastructure?

ANDREW HERRMANN: Yeah. When that fire broke out in Georgia it was quite the heat that brought down the concrete girders and also took out some of the piers. But you’re asking about the infrastructure conditions across the country?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

ANDREW HERRMANN: Well, ASC, as you know, puts out a report card every four years. And our latest report card covered 16 categories. We had 12 Ds three Cs one B for an average great point of D+. And our roads and our public transit received two of the lowest grades. Roads got a D, and public transit got a D-.

IRA FLATOW: Is there a common theme to why all of this, Ds and D minuses? Let me ask you, Andrew. And then ask you, Martin.

ANDREW HERRMANN: Well, basically it’s the lack of investment in our infrastructure. And the lack of maintenance and repair funding to keep it– the infrastructure we have in good shape. So when you don’t take care of the infrastructure that you have it tends to wear out faster than if you’re doing the normal maintenance and rehabilitations you should be doing.

IRA FLATOW: Martin?

MARTIN WACHS: I would agree with what was just said. But I would also say that a national report card for something as complex as a highway system can only be a broad signal as to what we have to do. In each particular facility and each particular metropolitan area the condition can vary very greatly from a national average like that. So we really have to pay attention to this at the state level, at the regional level, at local level, as well as at the national level.

IRA FLATOW: Let me bring in some listeners who can add some flavor to this and we can talk about what they’re seeing. Let’s go to Leigh in Springfield, Virginia. Hi, Leigh.

LEIGH: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there.

LEIGH: How are you?

IRA FLATOW: Fine. Go ahead.

LEIGH: So I’m in Springfield, Virginia, which is part of the Metro blue line. And rather than working on the infrastructure involving, oh, like the trains– I mean, we’re working on SafeTrack and things like that. But most recently they have decided to paint all of our stations white.

IRA FLATOW: That–

LEIGH: Which we have a very brutalist, concrete station design which never looks dirty. And rather than changing out our lighting and making sure the electrical is up to standards, and making sure that the light bulbs work, they decided that the way to make a brighter, well-lit station was to paint them all white.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s, let me– Martin, Andrew is this a common complaint you hear?

ANDREW HERRMANN: Martin, I don’t know. This is the first time I’ve heard of a complaint like this. I guess white will make it a lot brighter, maybe save some electricity. But I’m not sure how that goes in with the appearance of dirt in a subway station.

MARTIN WACHS: I certainly think that we should be concerned with the aesthetics of our stations as well as their condition. But I’m not sure that painting is a major, infrastructure decline issue.

IRA FLATOW: You’re saying that every region has a different problem of its own, if I heard what you were saying before.

MARTIN WACHS: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: How do you decide who is bleeding the most? And what is the politics of why these things are happening?

MARTIN WACHS: Well the politics is enormously different from region to region. So, for example, in New York when the Penn Station issue arose– there’s also the PATH, the Port Authority Trans-Hudson system, there are buses that go into the Port Authority bus terminal, and there are highways. And people can choose among all of those. And the use of information, information via the radio or information via your smartphone, can help you optimize your travel.

But in New York, the interesting thing is that, all of those systems are ancient and crowded. So the Port Authority bus terminal is in need of replacement. The PATH system is at capacity. The highway system is congested. So New York has an aging system. And it’s hard to add capacity to it in a very, highly dense, built up environment.

Los Angeles, by comparison, is building billions of dollars worth of new rail to add on to the system that it has, which is relatively incomplete because it relies primarily on highways. So that’s what I mean when I say it’s different in different regions. Los Angeles building a new rail system and New York having to renew a very old and very expensive system.

IRA FLATOW: Andrew, did you want to chime in on that, too?

ANDREW HERRMANN: Sure, sure. Especially in the New York City area you’ve had decades of under-investment at Penn Station terminal. It basically– it’s very congested. It’s crowded. You have a number of lines going in there. And it’s very difficult to do the maintenance that they have to do.

I mean, even when they were trying to get another tunnel under the Hudson. That’s been slowed down and hopefully will be coming in the future. But if they have more access they can do some of the maintenance they have to do. Right now they’ll have to shut down some of track to do that.

IRA FLATOW: I have a tweet from Lydia in Florida. She says, you’re looking for commuter complaints? I-95 in South Florida is the best place to begin. It’s a 24/7 rush hour traffic with nonstop construction.

ANDREW HERRMANN: I think some people in Washington DC area would dispute that it’s the worst. But it’s all around the country. It just depends on the times of day and the transit that’s available.

MARTIN WACHS: To me, one of the biggest challenges here is the question of governance. The federal government isn’t going to solve all of these problems in every region without active participation from the states and local governments. And so, in the New York area, for example, when the two governors are in a dispute over whose money should be building the tunnel under the river it takes longer and longer to make a decision. And the federal government isn’t really motivated to contribute greatly to it unless the states are on the same page. So one of the biggest issues that holds us back is our inability, in a democratic system, to come to consensus relatively easily on these complicated issues.

IRA FLATOW: But the president, President Trump, said he’s going to unveil a plan to invest more than a trillion dollars in infrastructure, and that would include the roads and bridges, this summer.

ANDREW HERRMANN: That’s interesting. When we did our report card put together we also put a cost of what we need to invest to bring our grades from that D up to a B. And over a 10 year period we’re looking at over $2 trillion. So the $1 trillion would start but it wouldn’t completely help us.

MARTIN WACHS: And it would have to be matched, in the New York area or the Atlanta area, with contributions from the state and the local government. It would have to go through environmental clearances. It would have to go through citizen participation processes. So, just making the commitment is a wonderful start. But the process that we have set into law in our society remains very complicated. And it it’ll be quite a while before the billion dollars can be seen in improved performance.

IRA FLATOW: A trillion.

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

IRA FLATOW: A trillion dollars.

MARTIN WACHS: Trillion, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: That’s just a matter of 1,000 times more.

MARTIN WACHS: Yeah.

ANDREW HERRMANN: The interesting thing about investing in infrastructure is that it has an economic advantage. When we came out with the report card we took a look at what would happen if we didn’t invest that $2 trillion over the 10 year period, and what it would actually cost. And we found out that the gross domestic product would decrease by almost $4 trillion and business sales would be lost in the town of about $7 trillion. So it’s amazing what that $2 trillion investment would pay back. Yet, we’re still having political squabbles over it.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with Martin Wachs and Andrew Herrmann about the infrastructure. And I have a tweet here coming out. Let me– let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Randy in San Antone. Hi, Randy.

RANDY: Hello. Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm.

RANDY: Yeah. Here in San Antonio there’s talk of expensive programs to beef up infrastructure, like light rail and such. But here we have developers that have had their way for many decades. They get concessions for cheap land. And then they put in hundreds of homes in any one setting. They sell the homes, take the money and run. And then we never hear from them again.

The cul-de-sac spaghetti networks that they put in a few ingress and egress points. And they’re overburdened and jamming up the adjacent thoroughfares, usually with unintelligent traffic lights that become a dependency. So I think that if they would continue to build the cul-de-sacs that they should be held accountable for the infrastructure, such as perhaps [INAUDIBLE] intersections in ways so that the thoroughfares are not interrupted.

IRA FLATOW: Right. There you go. So it’s not just things that are crumbling but it’s city planning that could be a problem.

MARTIN WACHS: Yes. In many cities there is an emphasis on smart growth, as they call it, which is transit oriented, which is older fashioned grids rather than cul-de-sacs. But it’s absolutely true that while we’re doing smarter development in the centers of cities the suburbs are still growing at the edge in the fashion that we became used to in the 50s and 60s.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. Well, getting back to fixing the crumbling infrastructure. Is it basically, we just– you know, there are taxes for gasoline taxes. And different states have different ways of paying for transportation. Is there a simpler– you talk about how complex the rules are and the system is– is there a way to simplify it so something gets done?

ANDREW HERRMANN: It’s interesting to talk about gas taxes. If we just raised our gas taxes a quarter a gallon we could raise a number of funds and help a highway trust fund. And that quarter a gallon would only result in maybe $100.00 per year for a driver who drives 12,000 miles. Yet, the cost of him right now driving due to poor roads can be anywhere from $350.00 to, in California I think is over $850.00, per year. So another $100.00 would start saving some money because we’d have easier and better roads to drive on.

MARTIN WACHS: Yes. California is actually raising the gasoline taxes by as much as $0.17 a gallon. We’re right in the process of it now. The first increase goes July 1st and then there’s another one November 1st. And I think the statement is absolutely correct that it’s a very productive investment in that it produces economic returns that exceed the costs. Yet, nobody wants their gas tax raised. And it was very hard for the governor to get this through the legislature. So it’s always the same story. People want the benefits that come from the spending but they don’t want to pony it up.

And I believe, and I think many of us in the transportation field believe, that it’s more equitable actually to charge the user through gas taxes and tolls than it is to charge the general public through income taxes and sales taxes. Because the people who benefit should be paying the costs.

IRA FLATOW: There you have it. It sounds like it’s going to get worse before it gets better. I want to thank my guests Andrew Herrmann, past president of the American Society for Civil Engineering and partner emeritus at engineering firm Hardesty & Hanover. Martin Wachs, professor emeritus of city and regional planning and civil and environmental engineering at UCLA. Thank you both, gentlemen, for taking time to be with us today.

MARTIN WACHS: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: After the break we’re going to talk about Richard Garwin, a scientist who has had a hand, basically, in creating everything from touch screens to the hydrogen bomb. Joel Shurkin, Genius is the name of his book. We’ll talk about it after this break. Stay with us.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.