The ‘Grandfather’ Of The Voyager Mission Retires

7:11 minutes

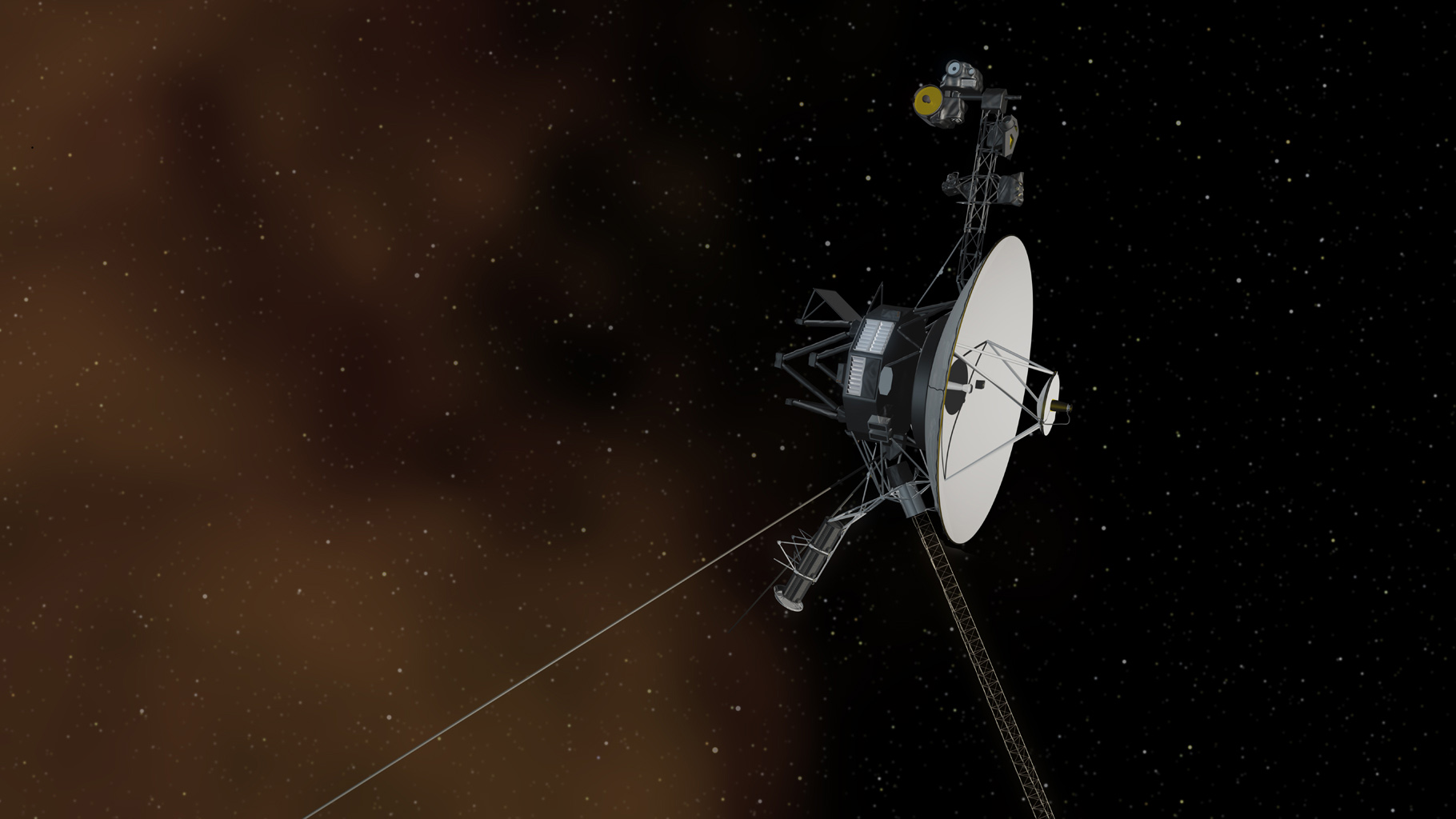

45 years ago, the Voyagers 1 and 2 spacecraft were launched into the cosmos from Cape Canaveral in Florida. Since then, they’ve traveled over 14 billion miles from Earth, on a grand tour of our solar system, and beyond. The mission is still running, making Voyager 1 the farthest human-built artifact from Earth.

Even before launch, scientists and engineers were hard at work planning and designing the mission. Last week, NASA announced the retirement of Dr. Ed Stone, who some called the ‘grandfather’ of the mission. Dr. Stone shepherded the Voyager program as its project scientist for 50 full years.

In this conversation from 2013, just after Voyager 1 had entered interstellar space, Ira spoke with Dr. Stone for a status update on the mission.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Ed Stone is the former Mission Scientist for NASA’s Voyager mission, based at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

IRA FLATOW: 45 years ago, the Voyagers 1 and 2 spacecraft were launched into the cosmos, setting off on their grand tour of our solar system and beyond. And even before they launched, scientists and engineers were hard at work planning and designing the mission– a mission that is still running, making Voyager 1 the farthest spacecraft from Earth.

Last week, NASA announced the retirement of Dr. Ed Stone, who shepherded the Voyager program as its project manager for 50 full years. Yeah, some called him the grandfather of the Voyager mission.

Back in 2013, I spoke with Ed for a status update on the mission just after the intrepid spacecraft had officially entered interstellar space.

Should I ask that question that I’ve asked every time– where is it, Ed?

ED STONE: Well, it’s now in the space between the stars, the interstellar space. It’s really on a new journey.

IRA FLATOW: Has it left the solar system?

ED STONE: Well, not really, you see, because the Oort Cloud of comets is also in the same interstellar space as Voyager is now. So that part of the solar system is actually in interstellar space.

IRA FLATOW: But the textbook definition that we all grew up with– the nine planets, now eight– that was always talked about the solar system. So it’s past the planets, then?

ED STONE: Oh, it’s well past the planets. That’s right. The outermost planet is Neptune, which is 30 times as far from the Sun as the Earth. And Voyager is now, when it entered interstellar space, was 122 times as far from the Sun as the Earth. So you can see, we are well outside of all the planets.

IRA FLATOW: Did you ever think it would get this far?

ED STONE: Well, we hoped. We didn’t know, of course. When Voyager was launched in 1977, the space age was 20 years old. So we had no way of knowing whether spacecraft could last this long or not. But they really have done it. These are the longest lasting spacecraft ever launched. And of course, they are by far the farthest traveling ever launched.

IRA FLATOW: And what was its mission when it was first launched?

ED STONE: The mission we had was very carefully defined to be a four-year mission to Saturn. And everything else after that was a bonus. We launched in 1977 because that was the magic year when a single spacecraft could actually fly by all four giant outer planets. But we did it stepwise, first to Saturn, and then we added Uranus, and then we added Neptune, and then we added the interstellar mission, which has been going now since 1990.

IRA FLATOW: And how have you been able to get it past Saturn, which was your original destination, to get way out there?

ED STONE: Well, we used the slingshot effect to propel the spacecraft. There was no problem in the sense of knowing how to get there. It was whether or not the spacecraft would actually survive and continue to function for that. Nobody knew that these spacecraft– there was no experience to say these spacecraft could work so well for so long and at such great distances from the Sun. The communication, of course, is 10,000 times more difficult out there than it is if you’re near, at 1 AU, only 1 AU away from Earth.

IRA FLATOW: What’s the size of the transmitter power?

ED STONE: It’s a 22-watt transmitter. But it’s focused generally toward the planets. And the signal strength itself when it gets to Earth– of the Deep Space Network– is something like a 10th of a billionth of a billionth of a watt.

IRA FLATOW: And it has one of these old tape systems on it.

ED STONE: It has an eight-track digital tape recorder. So it recorded the images during our planetary encounters. And now we record the wideband data from the plasma wave system, which is the system which in fact gave us the final information we needed that we were in the dense plasma of interstellar space rather than in the more rarefied plasma, solar plasma, that’s inside this bubble.

IRA FLATOW: Ed, tick off for us some of the major accomplishments from the Voyager.

ED STONE: Well, in the biggest sense, the most important planetary result was it really completely changed our view of the solar system. It revealed how diverse the bodies are in the solar system. Each one is unique. And that’s because geologic history affected each of them separately.

But it’s even more than that. That is, there are so many things that we thought we knew that we didn’t. Before Voyager, the only known active volcanoes in the solar system were on Earth. And then we flew by Io, a moon of Jupiter, a small moon, and it had eight active volcanoes, and it turns out 10 times the volcanic activity of the Earth. And so that was just the first step of greatly expanding our view of bodies and their evolution and their properties which, prior to that, was really based just on our more limited experience with Earth.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And you discovered all kinds of new properties about Jupiter and the other planets.

ED STONE: That’s right. Saturn, of course, we found its moon Titan had another nitrogen atmosphere, just like Earth, but even denser than the Earth’s atmosphere. But no oxygen. Instead of that, it has methane– natural gas– which rains on the surface. So that again, really sort of broadened, in a great way, broadened our view of bodies in the solar system.

And I always like to talk about the last body we visited, which is Neptune’s moon Triton. It’s the coldest body we visited. Only 40 degrees above absolute zero. So cold the nitrogen is in ice form in its polar region. Yet, we found geysers erupting at 40 degrees above absolute zero.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ED STONE: And before Voyager, the only known geysers were here on Earth. So time after time, our view had to be so greatly expanded. I think that’s the biggest, broadest impact of that part of the Voyager mission.

Now we’re on a totally different mission, which is the first to leave the solar bubble and begin to sail on the cosmic sea that’s between the stars. Because that’s what most of the Milky Way is, is the sea between the stars. It’s not the stars, but the sea between.

IRA FLATOW: In your experience– and I called you the grandfather of this project– are there any other spacecraft like the Voyager ever been built?

ED STONE: No. No, no. These are unique spacecraft. And I think they will remain so. Because, really, you do this sort of thing where you survey so much, so many new things, just once. The future spacecraft, as you know, have gone into orbit. Because the next phase of exploration is the detailed look you can get only when you’re in orbit.

IRA FLATOW: So what are your thoughts, Ed, today, now that this is all happening?

ED STONE: Well, I think it’s just remarkable, really. It’s remarkable. But I think, to put it in the larger context of exploration, this mission really has commonality with the first circumnavigation of the Earth and with the first footprints on the Moon. Now we have the first spacecraft actually measuring and observing in this realm which is filled with matter from other stars than our own Sun.

IRA FLATOW: That conversation with Voyager project scientist Dr. Ed Stone was recorded back in 2013. Best wishes, Ed, on a well-earned retirement.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.