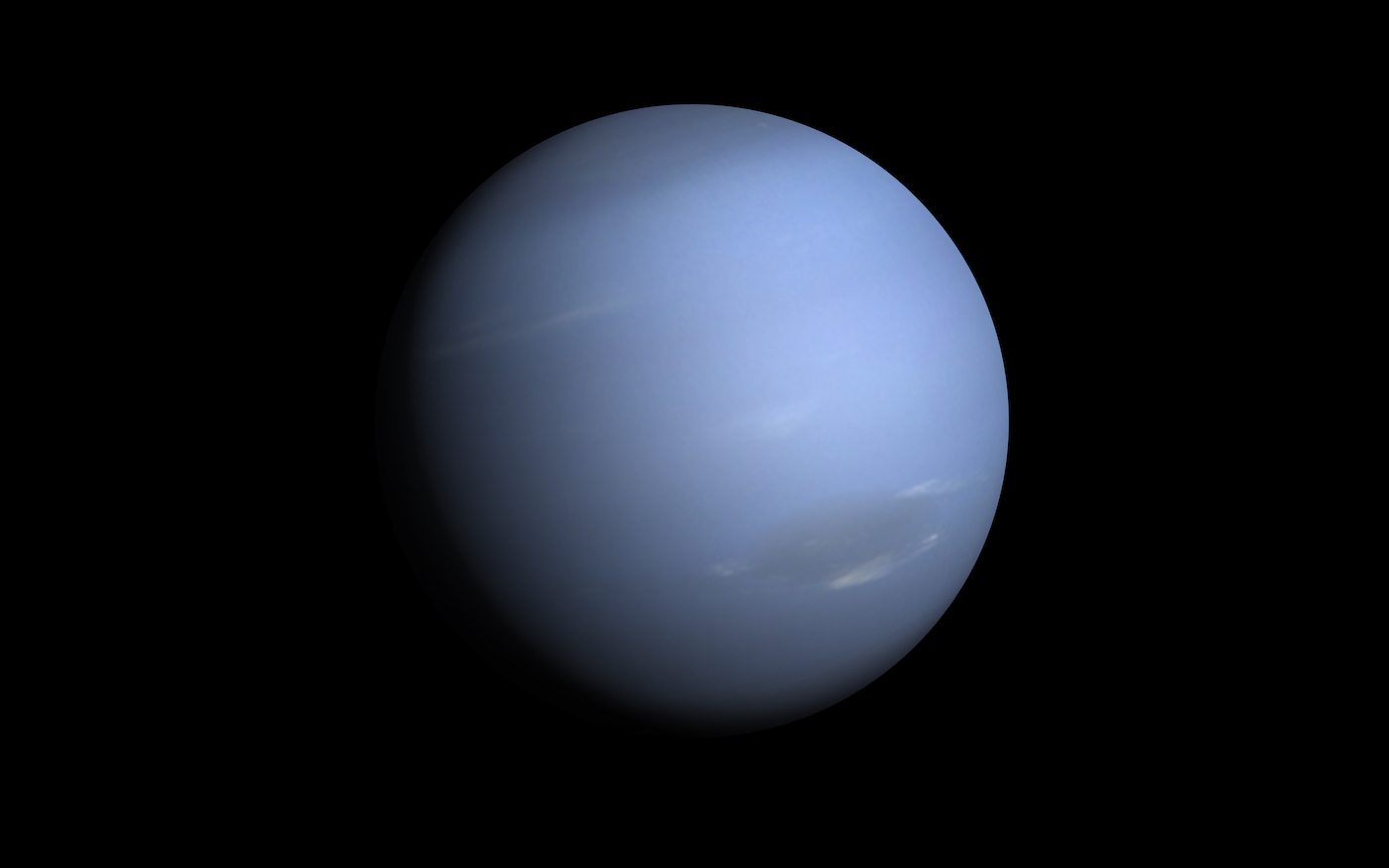

Might Uranus And Neptune Have Deep, Multi-Layer Oceans?

11:05 minutes

We’ve got a pretty good idea about what’s beneath the surface of our nearest planetary neighbors, like Mars. But as you get farther out into the solar system, our knowledge becomes scarce. For instance, what’s inside the so-called ice giants, Neptune and Uranus?

Recent research based on computer simulations of fluids hints that the planets could contain vast multi-layered oceans, as much as thousands of miles deep. A layer of water that is on top of—but doesn’t mix with—a deeper layer of hydrocarbons could help explain strange magnetic fields observed during the Voyager mission.

Dr. Burkhardt Militzer, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Berkeley, wrote about this idea in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He joins Host Ira Flatow to explain his theories.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Burkhard Militzer is a professor of Earth and Planetary Science and of Astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley in Berkeley, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’ve got a pretty good idea about what’s beneath the surface of our nearest planetary neighbors, say, Mars. But as you get further out into the solar system, our knowledge becomes scarce. For instance, what’s inside the so-called ice giants of Neptune and Uranus?

Recent research based on fluid simulation hints that the planets could contain vast, multi-layered oceans as much as thousands of miles deep. Joining me now to talk about that is Burkhard Militzer, Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Berkeley. He wrote about this idea in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Welcome to Science Friday.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Hello. It’s good to be back.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Well, why is it so hard to know what’s out there on these planets?

BURKHARD MILITZER: I think the main reason is they’re far away, and we have not visited them very much. We had just one spacecraft that flew to Uranus or Neptune and measured the magnetic field. And this single measurement told us they have weird magnetic fields. So that was the starting point of the study. But we haven’t been there that often.

IRA FLATOW: So you made computer simulations to figure out why there’s strange magnetic fields?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yes, we’ve done this for quite some time. And we put materials at high pressure, and we don’t do lab experiments. That’s what my colleagues do. I just pretend to do these things and put it on the computer, and then study, what do the atoms do in this case?

And in this particular case, when I put water and methane and ammonia in one box at really high pressure, the water mysteriously separated from the rest of it. That was the starting point of the study, because the water seems to not like, at these conditions, the carbon and the nitrogen system. And that gave us a clue what’s probably going on in these ice giant planets, we call them.

IRA FLATOW: And I have an image in my head of oil and vinegar in my salad dressing separating. Is that the same thing?

BURKHARD MILITZER: That is pretty much true. That’s the way you should think about it. But the problem is, planets are hot in the interior. And if you were to make the water and the vinegar really hot, they would mix. So what we’re proposing, that they don’t mix or phase separate, that is sort of radical. Nobody has done this before. But we think it’s real because it gives us a good explanation for the field.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Now, draw me a picture then. If your theories are correct, what might be on these planets? Describe them for me.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yeah. So the traditional view is you have hydrogen and helium, which is a top layer, and it has a little bit of methane. And it gives both of those planets a bluish color. So then the conventional wisdom was that there is this thick layer of water. So we’re not saying we’re the first one to say there’s water there. That’s the conventional wisdom.

What we are saying, that this thick layer, which we call the mantle, if you like, is split into two different layers. Just the upper layer is water. And then there is the carbon and the nitrogen, they’re actually below it. If you like, the oil is actually deeper in these things. And then there is rocks at the center of the planet.

So what we’re proposing new is that this middle layer, which people thought is just water, in fact has two separate layers. The upper one is water, and the one below is carbon and nitrogen.

IRA FLATOW: And how deep is this upper layer of water?

BURKHARD MILITZER: So the upper layer is actually 8,000 kilometers deep. It’s really, really thick. So you could put the whole Earth in this layer, because these planets are bigger. They’re about four times the size of Earth. And therefore, everything, all the different layers we’re proposing, they’re very, very thick.

IRA FLATOW: So 8,000 kilometers. 8 times 6, it’s like 4,800 miles, something like that.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yeah. That’s right. Yes. Yes.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Now, if this idea is correct, it would check off, as you say, this question of why Voyager didn’t see a magnetic field on these planets. Explain that a little bit more, why there would be the absence of the magnetic field.

BURKHARD MILITZER: So to be precise, we did see a field, but we didn’t see the type of field we were expecting. So if you look at Earth, it has a well-defined magnetic north pole and a magnetic south pole. And you find this on Jupiter and Saturn. And then you fly to Uranus in 1986, and the field is weird.

It looks like many more small north and south poles, and it doesn’t have this well organized structure that we see in the other planets. And that requires an explanation. Why is the field weird? And the proposal was, well, if you make this field just in a thin layer rather than in the thick mantle, a thin layer would actually make such a disorganized field.

But people didn’t know what this thin layer might be. So the proposal, we’re now saying this thin layer is this water layer that is not super thick, because this other layer underneath it doesn’t make the field. So that’s the novel interpretation, which we hope is right, but we don’t really know if it’s right till we have another probe that tests these things.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah. Are there other possibilities for why there’s this weird magnetic field?

BURKHARD MILITZER: I’m sure there are. But at the moment, we are the one explanation that we find very plausible. Other people just said, it’s just water all the way through in this mantle till you hit the rocks. And we find this implausible. I would say, at the moment, we have the most plausible explanation. But there could be others, and we don’t really know until we get more data from a future spacecraft.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hm. Now, this spacecraft were there. We’re talking about Voyager and the data that came back many years ago, right? Why has it taken so long for your simulations to yield some results?

BURKHARD MILITZER: So we struggled with this. We had this idea, and we pursued it in 2015. And we never saw this phase separation directly in the simulation. And the reason we now think was because we couldn’t simulate enough atoms. So we only had 100 atoms.

But then machine learning methods came along, and I could simulate 500. And 500 atoms, ironically, turned out to be enough, that the system will actually phase separate in two separate layers.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Now, I know that some researchers have theorized that these planets might have other weird things, like raining diamonds. I mean–

BURKHARD MILITZER: Oh, yes. Oh, yes. I know Marvin Ross. We overlapped in Livermore. He was a good colleague of mine. That happens. But the question is whether– it sort of happens at high pressure. There are lab experiments that show this. The question is whether this is actually happening in Uranus and Neptune. And the simulation that I’ve done is, diamond would not rain out because it’s too hot.

IRA FLATOW: Ah.

BURKHARD MILITZER: So that leads– that’s where we differ from the older theories, yes.

IRA FLATOW: I get it. Now, of course, the only way to test this would be, what, to send another probe out there?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Well, there are two things. So first of all, I talked to my colleagues at the Center for Matter at Atomic Pressures, and they do lab experiments. They should just take these materials, shock it with a laser to reach these extreme conditions, and see if they see the phase separation. That’s a good test.

And then the other test is actually to fly a spacecraft. And they will probably measure all sorts of things. And NASA is in the process of preparing a Uranus orbiter and probe mission. And I’m just advocating, you should bring the right instrument to detect such a novel two-layer structure in the mantle. That’s what we’re advocating for.

IRA FLATOW: Ah. What instrument would that be?

BURKHARD MILITZER: So it would be something that measures the oscillations of the planet. So it’s been done for the Earth. We call this free oscillations, or normal modes that oscillate. You do this with seismology. And it’s done for the sun. You just look at the sun. You can detect these vibrations.

And now we want to do this for Uranus or Neptune. If the vibrations have the right frequencies, then we can tell. So the frequency is a little bit like you’re listening to a bell that you can tell. And that helps you understand what the bell is made of, for example.

IRA FLATOW: It’s like when we detect earthquakes, we look for traveling through the Earth, right? The waves going through.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yeah. So our seismology colleagues, they do two things. When they want to understand the Earth, they look for earthquake waves that travel through the Earth, and some travel to the mantle, and some go to the core. And if you know how they travel, it tells us what’s in the interior.

But there is a different type of wave, and the Earth is sort of vibrating on its own without a triggering earthquake. And these are these free oscillations. And my seismology colleagues use both of those data sets to understand here.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Militzer, I’m going to give you my Blank Check question. If you had a blank check, you had all the money you needed, would you want to actually not land but send, let’s say, a diver probe, a submarine, something like that, into these planets?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Oh, yes. But you have to look back what you did with other probes. So if you have a solid surface, then you can actually land on these things. But Uranus and Neptune, most likely they don’t have a solid surface. And you end up in this situation, like with the Galileo probe that was dumped into Jupiter, and it had no mechanism to slow down.

So it was flying in there. It was getting hot very quickly. And it sort of got too hot at the modest pressures of 22 bars. So basically, most likely we will have another. There is an entry probe. It will measure something, maybe 200 bars. But if you have any way to slow it down, then you could make cool measurements. But at the moment, just the way it’s going, probably there’s no way to slow it down. And therefore, it will just die if it enters the atmosphere.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Well, how soon do we think this probe might get out there?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Well, that’s a sad story, actually. To be honest–

IRA FLATOW: No.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Because if NASA is really fast and gets everything together and Congress provides all the money we need, we might get there by 2050 and get measurements. And if I think about where I will be at 2050, I will most likely be retired. So I’m helping getting this off the ground, but I will not be the person who does the analysis, for sure.

IRA FLATOW: You and me both, Dr. Militzer.

BURKHARD MILITZER: I guess so, yes.

IRA FLATOW: We’ll meet back here. Thank you for– this sounds fascinating. Thanks for taking time to talk with us today.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Burkhard Militzer is a professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Berkeley.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.