Exploring The Body’s Hidden Wonders, From The Inside Out

17:10 minutes

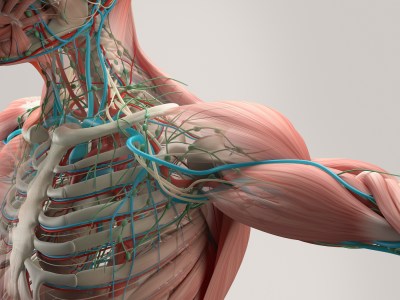

Most of us never get to see the inner workings of our bodies. Sometimes we get tiny glimpses when our bodily fluids make an appearance in the outside world—like a runny nose, a bleeding paper cut. But how well do we really understand what’s happening inside?

Internist and pediatrician Dr. Jonathan Reisman sees human anatomy as a reflection of the natural world. In medical school, he learned about each organ’s function and its role within the body. And it struck him that each organ is like a different species thriving in its own specific habitat, all while working within the body’s larger ecosystem.

In his new book “The Unseen Body: A Doctor’s Journey Through the Hidden Wonders of Human Anatomy,” Reisman explores the components of the human body. Reisman joins guest host John Dankosky to explain how he combines his passion for the outdoors and travel with his understanding of the human body.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jonathan Reisman is an internist, pediatrician, and author.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. Most of us never get to see the inner workings of our bodies. Maybe we understand, generally, that the heart pumps blood through our circulatory system, how the liver filters that blood, and that the air we take in to our lungs fills that blood with oxygen. And sometimes we get tiny glimpses when our bodily fluids make an appearance in the outside world, like a runny nose or a bleeding paper cut. But how well do we really understand what’s happening inside?

Our next guest is here to help us with that. Internist and pediatrician Dr. Jonathan Reisman sees human anatomy as a reflection of the natural world. In medical school, he learned about each organ’s function and its role within the body. And it struck him that each organ is like a different species thriving in its own specific habitat, all while working within the body’s larger ecosystem. Dr. Reisman is the author of a new book called The Unseen Body, a Doctor’s Journey through the Hidden Wonders of Human Anatomy. Jonathan Reisman, Thanks so much for being here. Welcome to Science Friday.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Thank you for having me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What made you decide to write this book in this way, drawing parallels between the human body and the natural world?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Well, before I ever started medical school, before I even wanted to be a doctor, I really fell in love with the natural world, and obsessively learned everything I could about every species of plant, animal fungus. I absolutely loved exploring new patches of wood, traveling to new countries, understanding new natural environments, including how different human cultures related to those unique environments. And when I started medical school and started exploring the human body, I basically, as you said, brought that same perspective of a naturalist and a traveler discovering some new terrain. In this case, that new terrain happened to be the human body.

I started learning all of the different body parts, the internal organs, the bodily fluids. Each did seem like a species in a new environment. Each had its own appearance, its own daily life, its own particular behaviors, both in health and disease. And I really became obsessively interested in learning absolutely everything about the human body, as I had about the natural world. I think it really crystallized for me when I understood that, as in the natural world, when we zoom out from examining an individual species, an individual organism, we can then take in the ecological perspective, the perspective of how individual species relate to each other and how every organism in a natural environment is interconnected in some way and each affects the other.

That same perspective came to me about the human body. And I understood that seeing the different body parts from the ecological perspective helped me understand how the body works, and also helped me understand a better perspective for practicing clinical medicine as well.

JOHN DANKOSKY: As I hear you say this and as I read your book, I guess I’m struck by the simplicity of that and how it might actually help us train physicians in the future. But that’s not the way that medical school is set up, is it?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Right. Well, there has been a trend towards more and more specialization as our knowledge of the body, as our knowledge of disease of various body parts, and as an increase in available treatments and diagnostics have only increased in recent decades. And to some extent, that is necessary. We do need specialists who understand the latest information about each organ, each body part. The amount of information out there is really staggering. And no individual could really know it all, so we do need some specialists.

I, however, am a generalist. And I love coming at the body from that zoomed out perspective to understand each of its parts, as well as how they interrelate.

JOHN DANKOSKY: The stories in this book are often drawn from the first time that you encountered something, like the first time you saw an organ in the cadaver lab or the first time you diagnosed a heart attack. What is it about these firsts that were so important for you to document in this book?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Just like when I was a lover of travel and exploring the natural world, it was always the first time that would be the most eye opening, the first time I went to a new country, the first time I experienced a new culture. That first time when you’re discovering, in many ways, a new world or a whole new perspective is the most eye opening. And that goes for travel for exploring the natural world and also for practicing medicine. I’ve since diagnosed heart attacks, too many to count really. But it was that first time that really was kind of a milestone for me and offered up this unique new perspective on the body.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Your first chapter in the book is about the throat. And you tell the story of a patient who’s elderly. And she’d been in and out of the hospital several times. And she was struggling with aspiration, food and water getting stuck in her airway. How did this experience make you think differently about the throat?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: When I was a medical student studying each body part, the throat was presented as a pretty stupidly designed body part where the air and food go into our bodies through the same entrance, the mouth. But in the throat, they must necessarily diverge. Food, drink, and saliva must go down the esophagus to the stomach and air must go down the airway into the lungs. And it did seem rather stupid because one small slip up, one incorrect swallow, if some food or drink goes down the windpipe into the lungs, to put it bluntly, you could die.

Every single time we thoughtlessly swallow throughout the day, food and drink come very close to going into the windpipe. And it’s this clunky, complicated mechanism of swallowing that keeps them out. Once I became a hospitalist, a physician working with hospitalized patients, I found that a lot of my elderly and infirm patients were suffering from basically the fallout of this seemingly flawed design. They were often developing aspiration, pneumonia. Because to make the throat’s dangers even worse, the icing on the cake, if you will, is that the world’s number one pneumonia causing bacteria actually lives in our throats just above the entrance to the lungs. So when we do aspirate, that food drink or saliva can bring those bacteria down into the lungs.

But when I cared for this particular patient, she had very advanced dementia, could no longer speak, recognize her relatives, or interact in any way. And she kept bouncing back to the hospital, getting one bout of aspiration pneumonia after the other. And it occurred to me that this very precarious design where we must juggle air and food perfectly throughout our lives, when it starts to break down in the elderly and infirm– those with neurodegenerative conditions like dementia, Parkinson’s, and strokes– in a way, it almost offers the body a way out from prolonged suffering.

And I think that is why, as I learned in medical school, aspiration pneumonia used to be called old man’s friend because it often does provide this end, a dignified end to prolonged suffering and illness.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You tell another story about visiting the hospital’s maintenance manager, whose name is Richard. And he shows you how the building’s plumbing worked. I’m wondering if you can talk about how this is similar and different to how blood flows to and from the heart, because we often think about this system as a type of plumbing.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Right. And I think plumbing is a very good metaphor for understanding not only blood flow, but the flow of virtually all bodily fluids that flow through our insides or outward from the inside. The heart, in particular, I think the cardiovascular system is how the heart pumps blood to all of our different body parts. Every little cell in the body must receive oxygen from the pumping heart in order to survive. And now, the simplest view of plumbing is that some fluid is flowing through a tube, and it can either spring a leak or it can become blocked.

And so much of medicine, actually, is getting rid of those blocks, such as blood clots. Anything from gallstones to kidney stones can block up the flow of their respective fluid and cause tremendous pain and suffering. Unclogging those clogs is a big part of medicine. But when you back up, again, taking in the bigger, zoomed out view, it’s not just an individual stream with a flow through it, but rather a branching system where different branches continue to branch further and further into smaller streams to feed every part of our body.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But as you say, when you zoom way out, veins and arteries might look more like rivers and tributaries as you view them from space.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Exactly. When I loved to travel before medical school– and still do– I really enjoy looking down at the Earth from a plane. And I found that the branching waterways that you see on the land was very similar to the branching blood vessels that we see in our bodies. And understanding how water relates to the shape of land how terrain shapes the branching patterns of streams, but also how streams, in turn, erode and shape the land, that give and take is very similar to what happens in our bodies and helps to understand disease and its treatment.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You described the body as a tube in the book. And it’s something that I guess I’ve never really thought about. Can you explain that for me a bit?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: So when we start as a fertilized ovum in the body, we develop first into a cluster of cells, and we flatten out into a little disk, basically. And as I say in the book, a few weeks into life, we roll into a little tube. And that design stays with us for the rest of life. We start as this tiny, little microscopic tube. And as we grow as a fetus and then grow as a human outside the womb, our body continues to enlarge and complicate. The front end of the tube sprouts multiple different entrances– through the nose, through the mouth, the esophagus, and trachea split off from each other.

And as we all know, the exit from that single tube also splits into exits for stool, for urine, and for the discharges of the gynecologic tract. And so as we grow into adults, we become a very complicated and adorned tube, basically. But that very basic blueprint still stays with us and explains a lot of what we find about the body’s design.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky. And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m talking with Dr. Jonathan Reisman. He’s the author of The Unseen Body, a Doctor’s Journey through the Hidden Wonders of Human Anatomy. You call urine, in the book, your favorite bodily fluid. So what’s so special about urine?

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Great question. I’m sure most people have never thought about what their favorite bodily fluid is. They’re all simply repulsive forms of waste that have to be discarded. But as I tell in the urine chapter, when I started studying to become a doctor, I discovered that each bodily fluid is actually a language. And as a physician, each of those bodily fluids is communicating to me what is wrong with my patient’s bodies, what is the cause of their symptom or the sign of their disease. And often, making a diagnosis actually means learning to read those messages, learning to understand the language of each bodily fluid, to interpret its consistency, its color, its amount, which often increases in illness, sometimes even its smell.

I found that urine is really the most fascinating of them all. Part of this is because it really provides a very impressive wealth of clinical information about my patients’ bodies. I use urine every day to diagnose diseases, both those affecting the urinary tract, but really affecting the body as a whole in systemic illness or even diseases that are affecting some body part far away from the kidneys and seemingly unrelated to the flow of urine altogether. So that, for me, is enough to already love urine as a useful bodily fluid for me to help my patients.

But beyond that clinical utility, I found that urine carries this extra message about where humanity comes from. So specifically, our ancestors lived in the ocean before they crawled out onto dry land, where we live now. And I discovered that the way kidneys work, the way they churn throughout our lives to extract urine from the bloodstream, the way they keep salt and water inside the body to prevent dehydration, but also the way they perfectly titrate salt levels in our bloodstream– they keep those salts in roughly the same proportions as the oceans that our ancestors used to live in.

And to me, that highlighted the fact that without the kidneys, we could never have left the ocean. We continue to carry the ocean inside of each of us. And the kidneys and the way they produce urine and the constant flow of urine is how that happens. And without it, we never could have adjusted to life on land.

JOHN DANKOSKY: In the book, something else that I guess might be a little bit unpleasant to some people, you detail your experiences eating different animal organs, like liver and lungs and brain. And it’s somewhat counterintuitive, , but it almost seems as though the more you learned about these body parts in cadaver labs, the more interesting you found them as potential food in animals. I wonder if you can talk more about that. Because it does strike me as, I don’t know, maybe the more I knew about the human liver, the less I’d want to eat a chicken liver.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Right. And I perfectly understand that perspective. And I believe I had that perspective before going to medical school. And specifically, anatomy lab, where we dissect the cadaver, I would say is where most people would go to lose their appetite, not to broaden it. For me, the opposite happened however. There was one professor who really enjoyed pointing out different muscles inside the cadavers, the muscles that we were learning all about. And he would explain which ones corresponded to different cuts of beef.

That really fired my imagination and led me to visit a slaughterhouse and to start learning about butchering. And I ended up learning all about butchering and how to prepare and eat different organs around the same time that I was learning anatomy. And I found, surprisingly, that they complemented each other well. And for instance, learning all about the complexity of the liver and how it oversees such a variety of important conditions, a variety of important balances in our body and how it keeps us healthy every moment, that fascination and that growing knowledge really led me to want to try it once again, even though in childhood, I had never enjoyed it.

And that fascination really helped me to enjoy eating it more. It is an acquired taste. But the medical knowledge, the anatomical and physiologic knowledge I was gaining helped me overcome that initial squeamishness. And the same was true for many body parts as well.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So most of us who aren’t doctors haven’t had this look inside the human body. I’m wondering how the rest of us who aren’t either medical specialists or generalists like yourself, what they could gain from understanding how our bodies work just a little bit better.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Well, I think one of the things that I loved most about learning about the human body was that there’s so many levels at which you can understand the human body. There’s the level of the individual, the whole body. You can zoom in to understand something on the level of an individual organ. You can zoom in further to the cellular level to see how that organ functions to keep us healthy. You can even zoom in further to the molecular level to understand biochemistry.

What I thought most fascinating was that, often, these different levels are intertwined in many ways. And sometimes when you zoom in to the molecular level, such as when you’re understanding how the kidney traits levels of salt in the blood on the molecular level, you’re, at the same time, zooming out to understand the history of humanity and where we came from and how we evolved. So sometimes, zooming all the way in to this very specific microscopic level, in many ways, for me, meant also zooming out to understand whether it’s the history and evolution of humanity, whether it’s the interconnected ecology of the natural world, whether it’s how different cultures relate to their natural world and to their own bodies how perspectives vary with culture.

For me, that’s the most fascinating. And I think understanding any part of the body necessarily leads to understanding it on the whole, as well as the universe outside of our bodies and how everything really is connected.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, it’s a fascinating look at the human body and our inner workings. I’d like to Thank Dr. Jonathan Reisman. He’s an internist and pediatrician. He’s based in Philadelphia. He’s the author of The Unseen Body, a Doctor’s Journey through the Hidden Wonders of Human Anatomy. Thanks so much for being here on Science Friday. I really appreciate it.

JOHNATHAN REISMAN: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.