Is Each Fingerprint On Your Hand Unique?

10:00 minutes

We often think about each fingerprint as being completely unique, like a snowflake on the tip of your finger.

But a new study shows that maybe each person’s fingerprints are more similar to each other than we thought. Researchers trained artificial intelligence to identify if a thumbprint and a pinky print came from the same person. They found that each of a person’s ten fingerprints are remarkably similar in the swirly center.

Ira talks with study author Gabe Guo, an undergraduate at Columbia University majoring in computer science, based in New York City.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Gabe Guo is a computer science undergraduate at Columbia University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

We’ve been told for decades in all kinds of ways– TV court dramas, newspaper reports, you name it– about how each of our fingerprints is unique like a snowflake right there on the tip of your finger. But a new study shows that maybe each person’s fingerprints are more similar to each other than we thought. How? Researchers trained AI– what else– to identify if a thumbprint and a pinky print came from the same person.

Joining me now to talk about what they found is Gabe Guo, study author and an undergraduate at Columbia University majoring in computer science based in New York. Gabe, welcome to Science Friday.

GABE GUO: Yes, thank you for having me today, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let’s get into this. What did you find? How similar are one person’s fingers to each other?

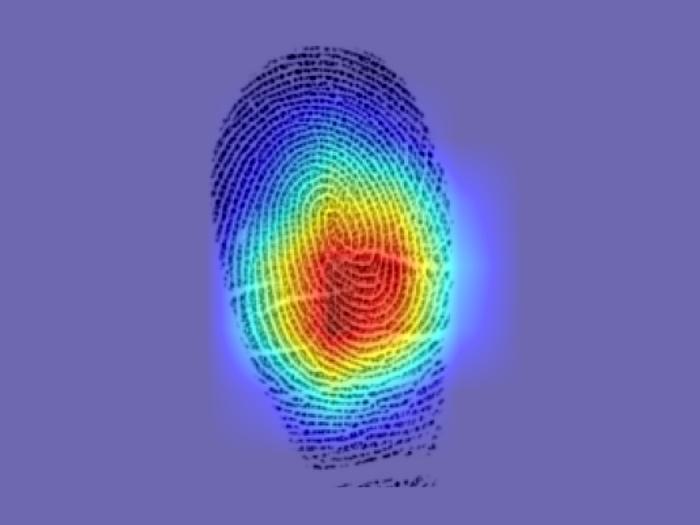

GABE GUO: Yeah, so in summary, we trained an AI to find very statistically significant similarities among fingerprints from different fingers of the same person. So that means, for instance, we now have characteristics that can link your pinky finger to your thumb, and as for what those characteristics are, it’s mostly due to the ridge angles near the center of the fingerprint, a region known as the singularity.

IRA FLATOW: The singularity. We love that word in science, don’t we?

GABE GUO: Yes, we do.

IRA FLATOW: How is artificial intelligence able to determine if the fingerprints from the same person were similar?

GABE GUO: We use a type of artificial intelligence known as a deep contrastive network. And I know that sounds really hard and fancy, but it’s actually pretty simple. I’ll break it down for you.

All it is an AI that tells you if two pictures are of the same thing or of a different thing. So, for instance, if I take a picture of a dog Bob today and then take another picture of Bob tomorrow and then test them both into this AI, it’ll say this is the same dog. But if I take a picture of my dog Bob and the picture of my cat Jim and pass them into the AI, then it’ll say they’re different. And we use that exact same strategy for fingerprints.

Now as for how we get this model to actually learn this, we just fed it a lot of data from a US government database. And this data had fingerprints from all different finger and some of them from the same person, some of them from different people. And over time after looking at this data, the AI just got better and better at finding the similarities and differences.

IRA FLATOW: So let’s go into what prior research suggests about the similarity of fingerprints. Didn’t we already know that one person’s fingerprints are similar to one another? What’s new here?

GABE GUO: Yeah, so there was previously a hunch that this was the case, but up until us, nobody was able to quantify it, identify the features that made them similar, and certainly nobody built an automated matching system. And, yes, there is previous research that influenced us, so I’ll list some of them.

There was some research that came out a few years ago that talked about the genetic determination of fingerprint patterns, and that was actually what led us to investigate this because if all fingerprints come from the same DNA within the same person, then there should be some similarity. And then another work that also inspired us to do this was a work that showed that of you have a fingerprint matching system trying to distinguish twins, it can still distinguish them, but the error is slightly higher when you’re distinguishing twins versus people who aren’t twins.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Speaking of interesting, how did you get interested in studying fingerprints? It’s not something anybody wakes up in the morning and says, hey, I want to study fingerprints. Well, maybe you did.

GABE GUO: Right. Totally.

IRA FLATOW: I don’t know.

GABE GUO: Yeah, so as with many Americans, this project of mine actually came about because I was super bored during the COVID pandemic. I was cooped up at home in Buffalo, New York– wonderful town– so I was having a chat with a professor from the University of Buffalo, Wenyao Xu. He’s a great family friend. And at the end of the chat, he just casually posed to me this question. Gabe, do you think all fingerprints are really unique?

And I said, What do you mean, Professor Xu? And he said, well, specifically those fingerprints on the same person. They come from the same genetic material. Surely, there must be some sort of discernible similarities right? And I said, I don’t know, Professor Xu. I’ll have to investigate that.

And little do they know that offhand 30-second exchange would literally take over the next three years of my life. So I worked on it while I was still in Buffalo that COVID year, and then I loved it so much that I asked Professor Xu if I could take it to Columbia with me when I started at Columbia. And he gave his consent, so then we collaborated with Professor Hod Lipson, who’s also very wonderful, and now we’re here.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. So tell me how the process of getting this published worked. You got rejected a few times, right?

GABE GUO: Yeah. And I think that whole process was very funny because while we were trying to get it published, one of the most common criticisms from reviewers is that, oh, we know that every single fingerprint even from the same person is unique, and that’s the– it speaks to the power of AI. It’s really upending these conventional beliefs we previously had.

So when we were faced with that criticism, we just kept running more experiments, providing better visualizations, and eventually it got to the point where our quantitative and qualitative evidence was so strong that it was incontrovertible.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you came up with the same roadblock that we see with doctors facing AI. Oh, I’m better than AI because I just know my stuff. Well, then you test it out, and you find out, uh oh, maybe I was wrong all these years.

GABE GUO: Right. And I think to your point, I don’t see AI as something that will replace human experts. Rather, I see it as something that can augment the capabilities of human experts because actually after this study came out, we got a lot of interest from police departments, forensic scientists, biometrics companies who are inspired by our work and want to use it to further the state of the art.

IRA FLATOW: We’ve all watched Law and Order or some other of these crime shows, and we’ve seen them taking all these fingerprints. Tell me how your research might be helpful in the field of forensics or even beyond.

GABE GUO: A crime scene’s fingerprints are usually hard to pick up. So typically at a crime scene, you’ll only get maybe one or two discernible fingerprints. Let’s say the right index finger. But the issue is what if law enforcement or your private investigator only has fingerprints from different fingers on file. Let’s say they only have pinkies.

Well, with previous techniques and fingerprint matching, it would be impossible to link them. However, with our technology, we’re the first in the world to find a way to actually match these fingerprints from different fingers of the same person. Thus we can catch this criminal and make sure that the criminal doesn’t cause problems.

But, of course, this is America, and we believe in freedom here, not just putting people away. And we still want our paper that when we use this method, we can actually narrow down the number of false leads that the law enforcement has to investigate by over tenfold. So that means for every one criminal that we choose to prioritize investigation on based on our technology, that’s at least nine other innocent people who don’t have to be unfairly investigated, and I think that’s a win for everyone.

IRA FLATOW: Is it precise enough yet to be used in crime scenes and in court?

GABE GUO: As currently constructed, we can’t use it as deciding evidence in court, but as we show in the paper, it’s very useful for generating leads. And I also want to add that in our research, we saw a trend where as you add more data, the precision and accuracy went up and up. And we only trained on 60,000 fingerprints, so I’m sure that if the FBI decides to train this with their millions of fingerprints, they probably could get it to a level where it might be used as evidence. But I’ll wait for them to make that call.

IRA FLATOW: Well, they haven’t– your phone’s not ringing then from the FBI?

GABE GUO: Oh, I’m not allowed to disclose that information.

[LAUGHING]

IRA FLATOW: Is it ringing from other law enforcement people, or are you now in some sort of patenting situation where you can’t disclose anything?

GABE GUO: Yes, it is being patented, and, yes, law enforcement agencies are contacting us. But I can’t speak more about that.

IRA FLATOW: I know you’re graduating in May. Congratulations.

GABE GUO: Yes. Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: What’s next for your research and your career if you can tell us, that is.

GABE GUO: So I’m going to be pursuing a PhD in computer science in the fall, and as for this research, this isn’t just a new paradigm of fingerprint recognition or even biometrics. It’s really a new era in AI because for most of AI history, all the time, effort, and funding went into teaching AI models to do things that, no offense, any human toddler could do. Is this a cat, or is this a dog?

Cool but now we have AI that isn’t just regurgitating information, not just doing simple things. It’s literally making new scientific discoveries and not just new scientific discoveries, new scientific discoveries about our fingerprints, which were in front of our plain eyes for hundreds and hundreds of years. And yet none of us noticed this until we had our AI look at it. So we now have AI that knows our own bodies better than we do, and to me the implications of that are just massive. So I want to embark on a journey of AI-assisted scientific discovery. That’s what’s next for my research.

IRA FLATOW: That’s terrific, Gabe. And will you keep us in the loop, come back and tell us what you’re finding?

GABE GUO: Oh, most definitely.

IRA FLATOW: Good luck to you and to your graduation.

GABE GUO: Yes, thank you very much, Ira. Pleasure to speaking to you.

IRA FLATOW: You, too. Gabe Guo, study author and undergraduate, soon to be a graduate at Columbia University majoring in computer science right here in New York.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.