Who Owns The Night Sky?

17:10 minutes

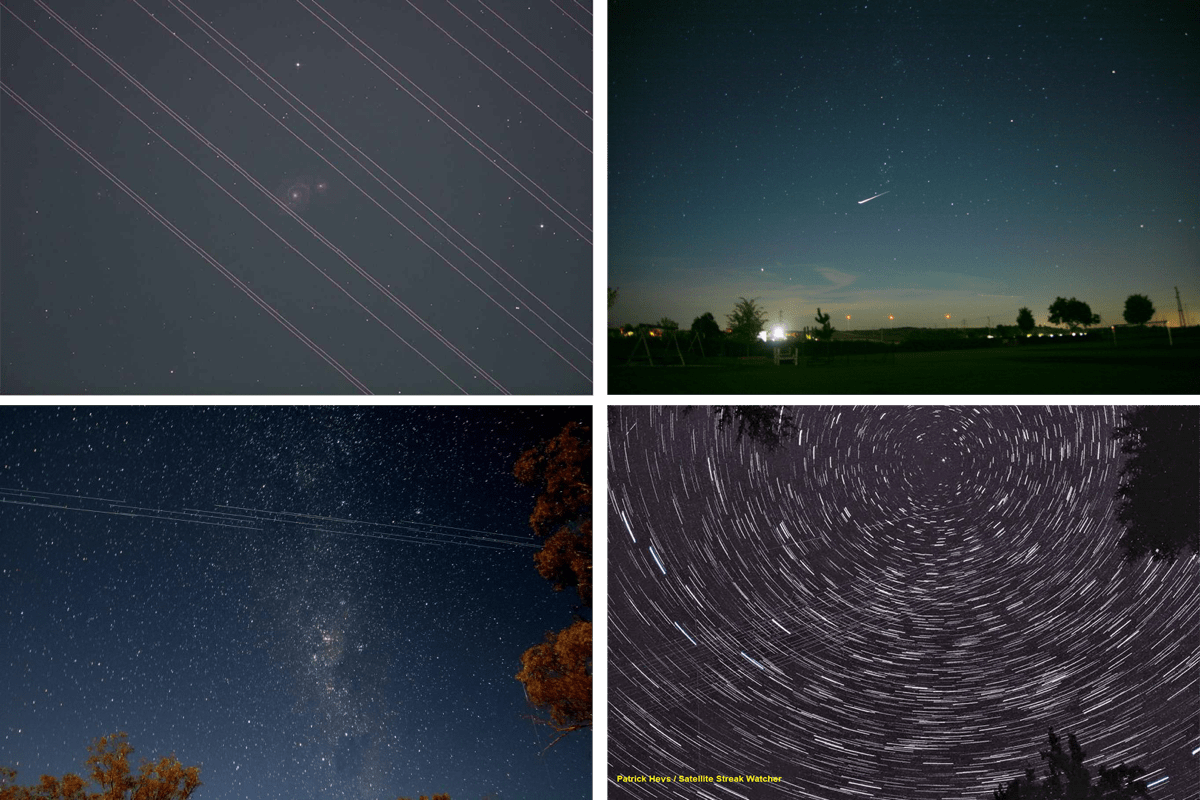

Grab your camera and look up! Anecdata’s Satellite Streak Watcher project needs your help tracking satellite populations in the night sky. Learn how you can participate.

In the last year, Elon Musk’s SpaceX company has launched more than 500 small satellites, the beginning of a project that Musk says will create a worldwide network of internet access for those who currently lack it. But there’s a problem: The reflective objects in their low-earth orbit shine brighter than actual stars in the 90 minutes after sunset. In astronomical images taken during these times, the ‘constellations’ of closely grouped satellites show up as bright streaks of light that distort images of far-away galaxies.

With SpaceX planning to launch up to 12,000 satellites, and other companies contemplating thousands more, the entire night sky might change—and not just at twilight. Astronomers have voiced concerns that these satellites will disrupt sensitive data collection needed to study exoplanets, near-earth asteroids, dark matter, and more. And there’s another question on the minds of scientists, photographers, Indigenous communities, and everyone else who places high value on the darkness of the night sky: Who gets to decide to put all these objects in space in the first place?

Astronomers Aparna Venkatesan and James Lowenthal discuss the risks of too many satellites, both to science and culture, and why it may be time to update the laws that govern space to include more voices. Plus, astronomer Annette Lee of the Lakota tribe sends a message about her cultural relationship with the night sky.

Plus, NASA is asking amateur astronomers and photography enthusiasts to take as many pictures as they can of the Starlink “streaks.” You can help NASA document the night sky—and the changes happening there—by uploading your sky photos to the Satellite Streak Watcher research project. All you need to get started is a digital camera or smartphone, a tripod, and a long exposure on a clear evening.

Research time! Share your experience with citizen science, and you’ll get a chance to earn a little pocket change, while helping us make citizen science more inclusive, fun, and meaningful for everyone. Learn more about the study and participate here.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Aparna Venkatesan is a professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of San Francisco in San Francisco, California.

James Lowenthal is a professor and the chair of Astronomy at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Summer nights are a good time to look up. Maybe you can see and name every constellation– I can’t do that yet– or maybe you’re still hoping to get a glimpse of the full majesty of a dark sky far away from human light sources. On the darkest nights, we can see 8,000 stars with our naked eye. But what if one day you looked up and you saw something unusual, maybe thousands of bright satellites speeding across the night? Well, that’s one possible outcome as companies like SpaceX begin to launch new communication satellites into low Earth orbit.

The Starlink Project, which aims to offer affordable internet to people who don’t have access, is just the first of a coming wave of projects that might fill the sky above us with thousands of new satellites. And if that happens, astronomers and others are worrying something important about the sky could be lost, something we as a species have loved for thousands of years.

Here to discuss are my guests Dr. Aparna Venkatesan, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of San Francisco, Dr. James Lowenthal, professor and chair of astronomy, Smith College, North Hampton, Massachusetts. Thank you both for joining us.

JAMES LOWENTHAL: Thank you. Nice to be here.

APARNA VENKATESAN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: James, what makes the Starlink satellite different from all the other satellites we have up there in the sky already?

JAMES LOWENTHAL: They’re big, and they’re bright. There were, before Starlink, maybe 20,000 objects orbiting the Earth that were tracked by the US government. About 2,000 of those were operating satellites. Only about 200 of those were visible to the naked eye. But all of the Starlinks that have been launched, which is now 480 and counting, are visible to the naked eye. And it’s because they’re in low orbit and they’re big and they reflect a lot of sunlight.

Many people have seen the Starlink satellites just after launch when they’ve sent one rocket up with 60 satellites, and they look like a string of pearls across the sky. All of them bright enough to see easily with the naked eye before they spread out in their orbit and then their orbit gets raised to the higher operating orbit. And by then, they look a little fainter but still visible to the naked eye.

IRA FLATOW: And there are going to be a lot more than we have now.

JAMES LOWENTHAL: There are going to be a lot more– 480 and counting. Every time they launch, they release another 60. This first phase will include 1,600 satellites.

IRA FLATOW: From what I understand, these particular satellites are only visible right after twilight when they’re still in range of the sun. Does this make it any less of a problem for astronomers and people who are looking to see a clear, bright evening sky?

JAMES LOWENTHAL: Yes and no. The twilight hours are not the hours when all astronomy is done, but even astronomy projects that need a dark midnight sky often use the twilight hours to do calibrations. And there are many astronomy projects that actually need the twilight hours, such as ones that look for killer asteroids. And furthermore, many of the satellites that are [AUDIO OUT] posed now tops 100,000 new satellites coming in the next 10 years. And those satellites will be visible all night long, even in midnight from many parts of the world at many parts of– during many parts of the year.

I fear almost every branch of astronomy is vulnerable to this new threat. When telescopes point towards the Large Magellanic Cloud and take deep image after image to try to unlock the mystery of how stars form, how planets are made, how the Large Magellanic Cloud interacts gravitationally with the Milky Way in ways that will let us understand more about galaxy formation, they are sensitive to a streak passing across the field of view from a passing satellite.

The current planned constellations of satellites could include so many bright satellites that every single image will have a satellite streak in it, making some of that science absolutely impossible. We are at risk of losing the projects that are protecting the Earth from potential killer asteroids, space rocks that are big enough that if they collided with Earth they would cause a catastrophic explosion. The very nature of the universe, dark energy, dark matter, our understanding of those things depends on results from ground-based observations that are now threatened by the satellite constellations.

IRA FLATOW: Unbelievable. Aparna, what’s your take on this?

APARNA VENKATESAN: It’s very complicated. The goal of these satellite constellations is laudable– to bring internet and connectivity to the globe. I think it’s especially important when you consider minoritized populations around the world. And particularly in this country, the digital divide is very real and needs solving. However, I think that process matters as much, if not more than where we end up. And who are the stakeholders here? And very importantly, who was not at the decision-making table? Because there’s a wealth of issues in addition to science– the sky traditions of people around the world, cultural practices, and just a whole host of issues.

IRA FLATOW: We talked to Lakota astronomer Annette Lee about the importance of the night sky to her Indigenous communities and what they stand to lose if we change the sky.

ANNETTE LEE: So in Indigenous astronomy, the stars are our oldest living relatives. The stars are the place where we come from, where you can understand we’re made of the four parts– the mind, the body, the heart, and the spirit. Our spirit is really star and comes from the stars and goes back to the stars.

So I like to think of it like we are just here temporarily on our human journey and we go back to that spirit form. We go back to the stars. This is temporary. So having that connection with the night sky is having that connection with where we come from, where we’re going, and the reason why we’re here on our journey on Earth. So in that sense, it’s a lifeline.

IRA FLATOW: That’s exactly what you were talking about, Aparna, how important the sky is to Indigenous peoples.

APARNA VENKATESAN: I think that there’s so much rich dialogue that’s possible here. I’m a cosmologist, and I would say there’s a wonderful common ground amongst all perspectives when we think of space as an ancestral global commons. As a cosmologist, I know that we are all star stuff. We have all been deep within stars multiple times at this point, and that’s the cosmologist’s perspective. But I’m very grateful to hear the view of the sky and the cosmos as our ancestors as well through the Indigenous perspective.

Going a little bit beyond that, I think the time is now and arguably was a decade ago about who space belongs to. Is it a shared resource that we hold in community trust? Is it a basic human right like food, air, water? And I would say dark skies are a basic human right. The sky is something that has connected us around the world and across the millennia, as you noted, Ira. And it’s essential for science and for cultural practices. It’s what makes us human, all of these different traditions– scientific, cultural, and personal.

IRA FLATOW: James, how do astronomers look at this? Do they consider what social impacts they may have? And I remember just a few months ago, we were talking about trying to cite a telescope on a Hawaiian mountain top, and there was push-back from the Indigenous people there?

JAMES LOWENTHAL: Thanks, Ira. That history of astronomers building telescopes on mountaintops, many of them sacred to Indigenous people, is certainly complicated and a fraught one. And I think it is worth considering it now in the current situation. In many ways, you might say the shoe is on the other foot. Astronomers used to think our work is the most important thing, science must go on, and we were not very good about listening to the valid and serious concerns of Indigenous people. And you might say we were part of a colonial enterprise that science was wrapped up in. And now we’re suffering from that same colonization, only this time it’s the colonization of space.

Space is now essentially unregulated. The constellations of low Earth orbit satellites that have been launched and are proposed for launch– over 100,000 in the next 10 years– are legal. Most of them got the permission they need already from the relevant governing bodies like the Federal Communications Commission, and they’re even consistent with the United Nations Treaty on outer space.

It seems now possible SpaceX has devoted significant resources in the last year to making the satellites darker. It looks as if they’ve been able to do that. If other satellite companies could follow suit and follow a few recommendations, then perhaps we could save the sky for naked-eye star gazers. But that is not going to solve the problem for research astronomy. It is literally an existential threat for astronomy.

IRA FLATOW: Aparna, if they do darken the satellites with some kinds of shading, is research astronomy still threatened by the satellites just being there?

APARNA VENKATESAN: Yes, there’s multiple considerations. One is the contribution, as James well put it, both at a research astronomy level– is this spoiling my galaxy exposure, is this affecting my science– to space debris is a big one and collisions between satellites, also interference at other band passes.

As I’ve educated myself on this issue, I’ve been really surprised at the lack of consistent international regulation and transparent protocols on how we are literally occupying space. I know we have the Outer Space Treaty from 1967, but at the time there was a race to literally occupy space, to be the first there, and that strategy is still driving even our policy with the moon like a rush to claim– kind of a first come, first claim approach.

But I would advocate there is a huge opportunity right now, 60 years later. We’re entering this with very different pre-existing conditions than the 1960s because our planet and our species and really all species are at an existential crossroads. We’re very vulnerable, and I think we should move away from a scarcity mindset and a defensive reactive strategy to a more proactive strategy, one that begins in intentionality and respect. And we need to develop ethical and transparent protocols ahead of the science. And I know it’ll be slow and messy, but we’re really at a crossroads. And now is the time to revisit the process.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring back Dr. Annette Lee again with her hopes for what comes next.

ANNETTE LEE: I think that we’re too far along this path to hold the flood back. What we absolutely and urgently need to do is find a way to do both for the benefit of all. The question is, how do we do that now? Where are the policies? Where are the leaders? Where are the voices? Who is going to make that happen?

IRA FLATOW: Just a reminder, I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. A good question. That is the missing piece– who are the leaders? Aparna, you can answer first.

APARNA VENKATESAN: I think what we need is more representation at the decision-making table, both of international communities and all the groups advocating for dark skies. There’s so much sliding by that we are not able to pay attention to, and the first step is to have an advocacy group in our federal agencies.

I personally think NASA should have a cultural ethics or a cultural protocol office that can partner with all the other aspects of what we as astronomers do. The White House issued an executive order on April 6 asserting a right to recover and use space resources. And there’s a quote here that I’ll read out. “Americans should have their right to engage in commercial exploration, recovery, and use of resources in outer space consistent with applicable law. Outer space is a legally and physically unique domain of human activity.” And I’ll draw your attention to this end of the quote. “The United States does not view it as a global commons.”

So that’s very alarming to me, and the keyword for me is “applicable law.” The laws need to change. Right now, it’s just a couple of regulatory bodies. Then bring more historically minoritized voices to the decision-making table.

IRA FLATOW: And one final question for you, James. How do we get this as part of the discussion to begin with?

JAMES LOWENTHAL: I want to point attention to the United Nations Treaty on the use of outer space, which includes the phrases that “the exploration and use of outer space should be carried on for the benefit of all peoples irrespective of the degree of their economic or scientific development,” and also that “such cooperation will contribute to the development of mutual understanding and to the strengthening of friendly relations between states and peoples.”

These are lofty goals enshrined in the United Nations. And I’m happy to say that there is currently an international conference being planned for October that will result in a white paper to the United Nations about light pollution including from satellites, with the hope that we will be able to provide some more teeth to those treaties.

It also needs to happen, as Aparna said, updating of federal United States laws and other countries’ laws. Right now, the National Environmental Protection Act does not include protection of the sky. The sky is not considered the environment that needs protecting. Now we can see it desperately does need that protection.

IRA FLATOW: I think we’re out of time. So much to talk about. We have begun the discussion. I’d like to thank my guests, Dr. Aparna Venkatesan, professor of physics and astronomy, University of San Francisco, Dr. James Lowenthal, professor and chair of astronomy, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts. As I say, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

APARNA VENKATESAN: Thank you for this opportunity.

JAMES LOWENTHAL: Thank you. It was a pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: One last thing before we go. We’ve been talking about who makes the decisions about the night sky, and one thing that’s sure is that SpaceX is continuing to put their Starlink satellites up and NASA wants you to photograph them. So if you have a smartphone or digital camera, a tripod and can take some long exposures, you can help astronomers document these changes to our night sky. Here’s how to do it. Go to our website at ScienceFriday.com/satellites to learn more about the Satellite Streak Watcher Project and get started. NASA’s Sten Odenwald, director of Citizen Science for NASA’s Space Science Education Consortium, is here to motivate you.

STEN ODENWALD: I need lots of people from a variety of vantage points around the world to take a photograph of the sky during the transit times. Over the next 5 to 10 years, we can document just how bad things are getting. [LAUGHS] It would be a unique archive that will probably stimulate a lot of research once we build up enough of these images.

IRA FLATOW: NASA wants to track the growing footprint of these satellites over the next few years, so grab your camera, get outside, and check out our website for more details, ScienceFriday.com/satellites.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.