To Milk A Tick

17:26 minutes

Ticks are masters of breaking down the defenses of their host organism to get a blood meal. They use anesthetics to numb the skin, anticoagulants to keep the blood flowing, and keep the host’s immune system from recognizing them as invaders and kicking them out. And the key to understanding this is in the tick’s saliva. Biochemist and microbiologist Seemay Chou discusses how she milks the saliva from ticks to study what compounds play key parts in these chemical tricks. She also talks about how ticks are able to control the microbes in their saliva.

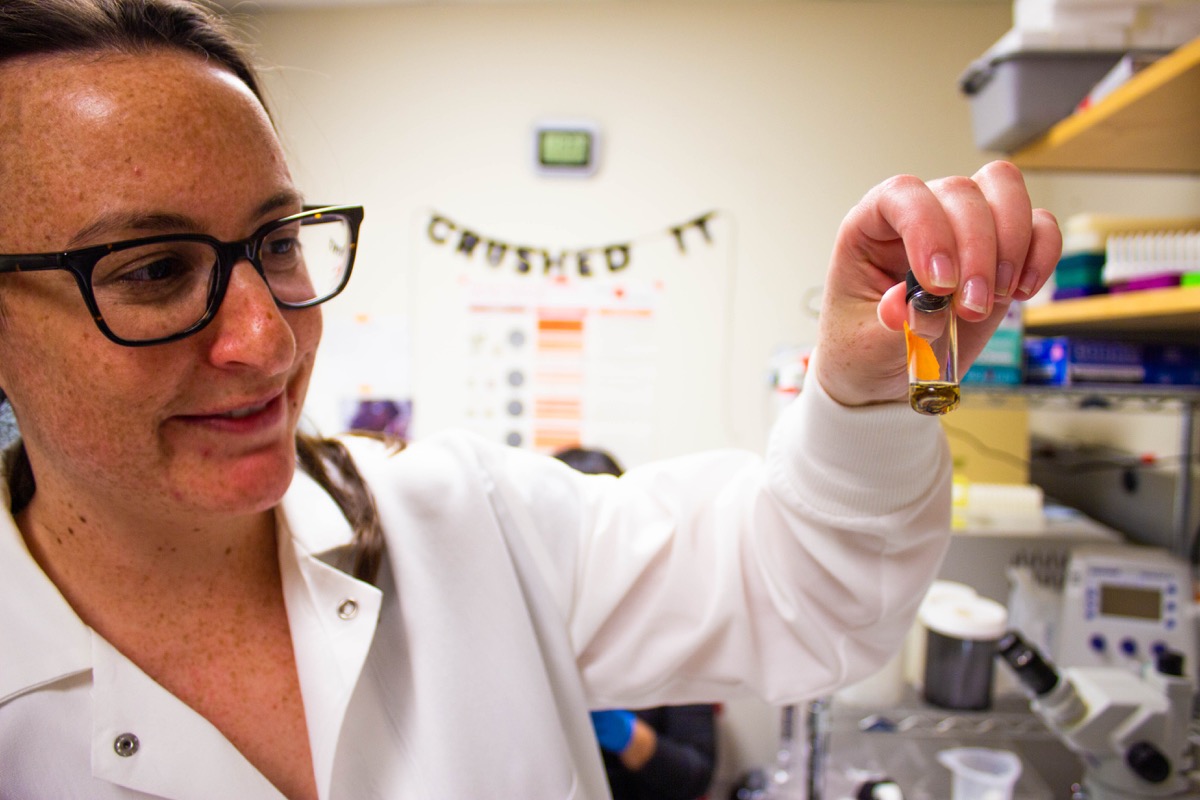

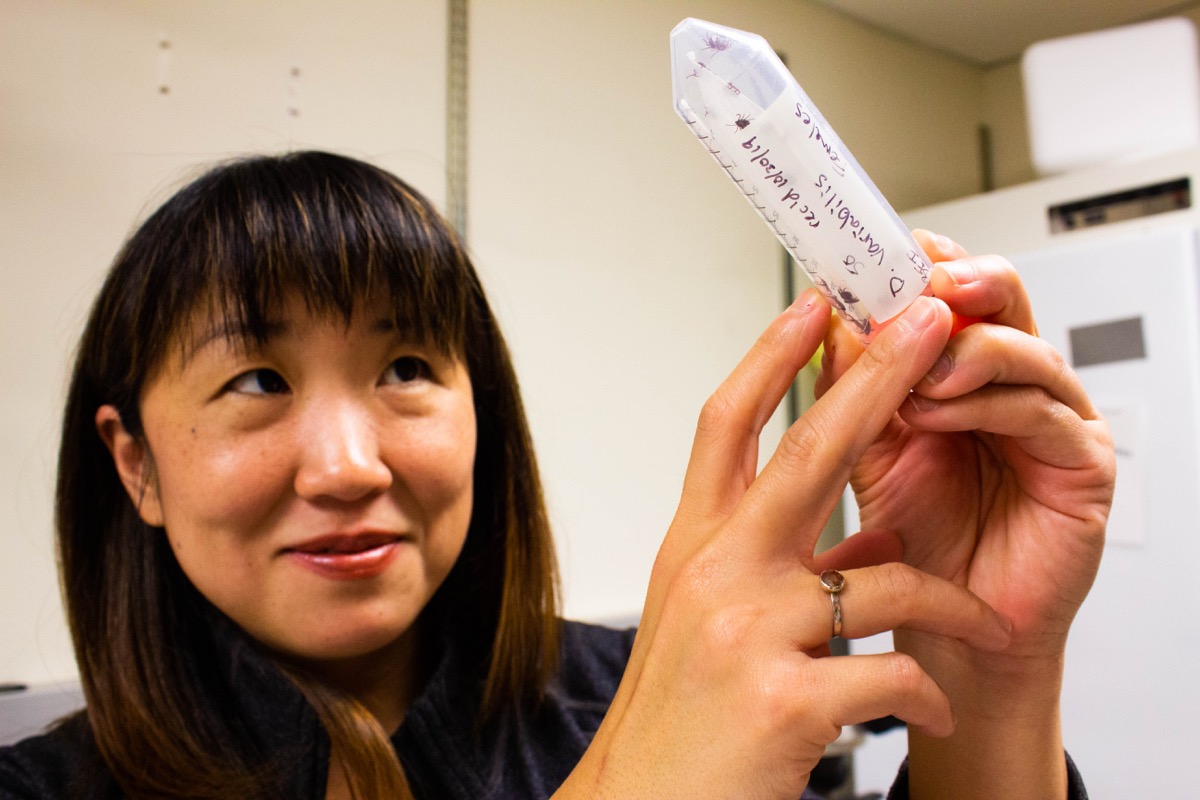

SciFri took a visit of Chou’s tick lab at UCSF. See photos of the team’s work below!

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Seemay Chou is an assistant professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of California, San Francisco.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Ticks are full of tricks, chemical tricks. They use anesthetics to numb your skin, inject anticoagulants to keep the blood flowing. They’ve also figured out a way to get around not only your immune system, but different types of host organisms. And did you know that they harbor microbes and somehow control these bacteria so that they don’t get infected by the microbes?

That’s all kind of interesting stuff. And the key to understanding how these tiny creatures accomplish this is in their saliva. And this could be used for treatments for tick-related illnesses. My next guest is what you might call a tick wrangler. And she studies ticks by milking them.

And you can see photos of her tick-filled lab at sciencefriday.com/ticks. Welcome to Science Friday. Seemay Chou, Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of California in San Francisco, she’s here at the studios of KQED.

SEEMAY CHOU: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: I’m trying to figure out what a tick lab looks like.

[LAUGHTER]

Describe your laboratory.

SEEMAY CHOU: It actually looks a lot like any other lab. The only difference is that we have a room that’s closed off, that has what looks basically like a refrigerator of ticks inside. And we wear white coats in there to make sure we can see them if they’re on us.

IRA FLATOW: You know, I’d be afraid of them getting out. Do they get out and you know feel something biting you?

SEEMAY CHOU: No, we’ve never had any get out. And I think UCSF Safety Administration would also share that concern with you. But I have had a tick on me from elsewhere. Have you ever had one on you?

IRA FLATOW: Yes, I have. I live in Connecticut. So we’re the capital of Lyme disease. So we’re always careful about these. And the Lyme tick is really tiny.

SEEMAY CHOU: Uh-huh, uh-huh.

IRA FLATOW: They’re not like the bigger tick.

SEEMAY CHOU: Well, there’s a couple of different life stages. So you probably saw one of the more juvenile stages on you.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And how did you get interested in studying ticks?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. I came about it through kind of a roundabout path. We were actually studying how bacteria compete with each other, completely independent of ticks. And we found that some of the toxins that they use to kill each other were basically stolen over the course of evolution by ticks and are now found in the genome of ticks. So we started probing how the ticks were using these antibacterials to try and kill off some of their own microbes. And then I got hooked.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So you’re milking them now.

SEEMAY CHOU: Yes, we’re milking them as well. One of the things we found is that the antibacterial we are studying is really enriched in the saliva of ticks.

IRA FLATOW: Ah.

SEEMAY CHOU: And so we think that they’re using this agent basically to kill off bacteria that they might encounter naturally when they’re feeding. And so we just got deeper and deeper into the world of spit.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: I love it. So if you figure out how they can fight the bacteria off, then the logical extension is how we might be able to use our knowledge about that.

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. And I really think that’s just the tip of the iceberg in terms of what we can learn from saliva. As you alluded to at the beginning, they do a lot of different things with their saliva because they’re feeding on us for days to sometimes over a week. So they really have to figure how to make a home and go undetected.

IRA FLATOW: Uh-huh. I once interviewed a biologist who studied spiders.

SEEMAY CHOU: Uh-huh.

IRA FLATOW: And her job was to milk spiders for the venom. And she had a little video. Do you know what I’m talking about?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yes, I do.

IRA FLATOW: I think Binford was her name. I can’t remember. It’s so long ago. And she played a small voltage to the spider and got it to eject its–

SEEMAY CHOU: That’s pretty awesome.

IRA FLATOW: How do you do it? How do you milk them?

SEEMAY CHOU: So it actually wasn’t figured out by us. It was figured out by some researchers long ago. But we found this old paper.

And you basically take the ticks. And you feed them partially on an animal, a mouse in our case. And then you can pull them off the mouse. And then we use very glamorous Scotch tape to tape them down. And then put a chemical called pilocarpine, which is used to enable both us and ticks to salivate.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm.

SEEMAY CHOU: And then you put what looks like a little glass straw on the feeding organ of the tick. And eventually you pull out quite a bit of saliva through capillary action.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. OK, let’s talk about ticks in general. Is there a mythology that people have? They think ticks do this, but they don’t actually?

SEEMAY CHOU: Oh, I mean I think the number one thing I run into is that people think ticks jump and fly. And they don’t.

IRA FLATOW: They don’t.

SEEMAY CHOU: Nope. No, they don’t. They don’t have the muscles in their legs to do that.

IRA FLATOW: So how did they get on you?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. So they do something called questing. When they’re in feeding season, they basically climb to the tops of shrubs or grass, places where they may run into animals walking by. And then they are really adept at sensing our carbon dioxide, our body heat, other things that would indicate that an animal’s nearby. And they raise their little legs up and latch on when you walk by. And it kind of looks in the lab like they’re reaching out, looking for a hug.

IRA FLATOW: Do they live in your grass if you have a lawn? Are they living in the grass or are they living in the shrubbery next to it?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. I think it’s context dependent. In some parts of the USA, they really like the grass. And in some parts of the US they are more in the shrubs. I think it really is an indicator of whatever ecology they’re surrounded by.

IRA FLATOW: Uh-huh. Let’s talk about– you’re interested in the saliva.

SEEMAY CHOU: Uh-huh.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me what is so fascinating about the saliva?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. I think studying the saliva actually gets at one of the kind of creepiest things about ticks because the fact that you can have a tick on you and not even know it– I mean I think that’s why a lot of people are kind of both fascinated and creeped out by ticks. But that is an indication that they’ve used their saliva to completely block your ability to sense it. Block a lot of the alarm systems that are normally in place to help you detect them.

So as you mentioned, your immune system, normally if you have some sort of mechanical wound, you would expect that there would be a raised bump or something, or itch and pain. These are all really annoying, but useful things we have to help us know that something’s there.

And so we’re really interested in mining what’s in the saliva to try and understand these processes because ticks have basically hacked our system. And if we can kind of use them as a muse, can follow what they figured out, we can have these clues to understand our own bodies more, too.

And then the second reason is that the microbes have really exploited this as well. We’re sort of late to the game. The microbes use the ticks as vectors. Meaning that they reside in the ticks and are able to be transmitted to their next host through the tick bite.

And, in fact, there’s a phenomenon known as saliva-activated transmission, which means that the microbe is enabled by the saliva. And without it, it would not actually be able to survive or spread in our body as effectively. So they’ve done these old experiments where they injected the Lyme pathogen, Borrelia burgdorferi. And without tick saliva coinjected with it, your body is quite effective at clearing it.

IRA FLATOW: So somewhere along the line in evolutionary history of the tick, it picked up this method of disguise, so to speak?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah, presumably, long ago. I think these are mechanisms that ticks didn’t evolve on their own. But they’ve been, yeah, acquired and expanded upon.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So mosquito bites are not the same thing.

SEEMAY CHOU: Oh, ticks are way superior to mosquitoes, for sure.

IRA FLATOW: Do they know that?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. Mosquitoes, they don’t make a home in us the way ticks do. As you know, they just need to be there long enough to bite and then fly off. Whereas ticks have to make this blood meal happen, without it they can’t transition to the next life stage.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. OK, so when I was a Boy Scout many, many years ago, there was always a chapter on hiking and whatever.

SEEMAY CHOU: Uh-huh.

IRA FLATOW: And what to do to prevent a tick– getting bitten by a tick. And once you get bitten, how to remove the tick.

SEEMAY CHOU: Uh-huh.

IRA FLATOW: We were taught either, take a match, blow it out. The heat, if you put it on the head of the tick, it will back itself out. There was somebody who said use Vaseline or oil to coat the tick. It will come back out. Any of that stuff legitimate?

SEEMAY CHOU: I mean, honestly the easiest way to do it is just take a pair of forceps and pull vertically. You got to pull perpendicular to your skin.

IRA FLATOW: Straight up.

SEEMAY CHOU: Pull hard enough that you kind of feel this pop of it really releasing from your skin. Because its feeding organ kind of has these spikes on it that dig into your skin. So you really gotta break past that.

IRA FLATOW: So if you do it the wrong way, you can make things worse. You could squeeze it and you get more saliva injected in there?

SEEMAY CHOU: You know, I think mostly you just don’t want the leftover residue of the tick debris in your skin.

IRA FLATOW: You want make sure that whole– we were told you got to get the head out.

SEEMAY CHOU: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: You got to get the whole head out there. Or else you just really–

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: And as far as the small ticks, like the ticks that are tiny to see, that we were trying to get out, how do you look for them because they look like tiny little freckles on you.

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. Those are really, really hard.

IRA FLATOW: The Lyme disease ticks.

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. Well– so there’s actually three life stages. The ones that look like freckles are the youngest ones. They’re the larvae. And those cannot transmit the Lyme pathogen to you because they have to acquire it from their first blood meal. And if they are feeding on you, you are their first blood meal.

IRA FLATOW: Uh-huh.

SEEMAY CHOU: And so the ones you need to worry about are the next level up, which are more the size of a large cracked pepper or the adults, which you can clearly see. But those– you know, really just paying attention after you go hiking. Or even for a few days after, because sometimes pets can track them in. A hot shower after you go hiking can help. Having some lab mates look you up and down, fiddle through your hair.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, right. Our number, 1-800-844-724-8255, if you’re listening, 844-724-8255. You can also reach us at Science Friday– at scifri.

How did you decide? I asked you before. But did you just wake up one day and say, oh, I’m going to study ticks. Or did you come from a different insect?

SEEMAY CHOU: No. I had never worked with– and by the way, they’re not insects.

IRA FLATOW: OK. You got me on that one.

SEEMAY CHOU: They’re arachnids. But no, I had never worked with an arthropod in my life. I had never even seen a tick when we first found these genes in bacteria. So it was meant to be a very short foray into this area, that I was just going to figure out what they were doing in ticks and move on. In my mind, it was like a six-month foray.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SEEMAY CHOU: It turned into a couple of years of really learning about the biology of ticks. And just the deeper you go, the more you want to learn. So that’s basically how I started.

IRA FLATOW: And what thing mostly would you like to learn? What don’t you know that you would like to know about ticks, how they spread disease, maybe there’s saliva?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. I mean, I think– one of the things that my lab is really interested in, that extends beyond just the people that are working on ticks, is we’re interested in understanding why bacteria have such specific associations with different hosts? And so ticks are a great system to study that because the pathogens that they carry are restricted to only a few species per pathogen.

And so there is this phenomenon called vector competence, where we have these really unique and limited relationships between one pathogen and one or two or a few different tick species, even though there’s a lot of other tick species that we can encounter. And this is true beyond ticks. It’s also true for mosquitoes and fly vectors. But I mean even beyond that, just animals–

IRA FLATOW: Animals.

SEEMAY CHOU: –how they associate with microbes. So this is one way that we can study this problem by looking at why it is this bacterium is really preferring this tick host and is able to thrive in this environment?

IRA FLATOW: Uh-huh. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Talking ticks with Seemay Chou, Assistant Professor, Biochemistry and Biophysics, at UC San Francisco.

For the ticks that have the bacteria that cause let’s say Lyme disease, why doesn’t the tick itself get infected with Lyme disease?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. So this is hitting on an important aspect of the biology, which is that these microbes are pathogens to us as humans. But they’re not pathogens necessarily to the ticks. In fact, the reason they can co-exist so well is because they’re living in harmony. So they’re more of what we would refer to as a symbiont or a commensal, which has a more neutral or potentially beneficial relationship with the host. And conversely, could be true. Some microbes that are commensal to your skin could end up being pathogenic to the ticks.

IRA FLATOW: So is it that the Lyme doesn’t recognize the tick as something to attack or is there something about the tick that defends against? Or is there sort of a symbiotic thing going on here?

SEEMAY CHOU: That’s the million dollar question. I mean, we think it’s probably a combination of the two. That’s certainly what studies in other systems would suggest. So we’re really just at the beginning of figuring all of this out. I think it’s probably a combination.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And there is a bit of a West Coast, East Coast split that happens with ticks, right?

SEEMAY CHOU: Oh, yes. West Coast, best coast.

[LAUGH]

IRA FLATOW: I’ll ignore that. No, I’m in California. I have to be very nice.

Ticks in California prefer to bite lizards, is that right? And Eastern ticks like rats.

SEEMAY CHOU: Correct. So on the West Coast there’s a tick called the Ixodes pacificus tick, which can intrinsically carry and transmit the pathogen for Lyme. But the reason we’re kept safer on the West Coast from this is that these ticks prefer to feed on lizards, which do not carry Borrelia burgdorferi. So because their blood meal host partner doesn’t have it, most of the time they don’t have it. There are situations– if a lizard is no available, that they can feed on other animals, like squirrels, that may be carriers of it. And then that’s where we run into some problems.

IRA FLATOW: So I was going to follow up on that. So if a East Coast tick makes it to the West Coast– and we all travel on airplanes, whatever–

SEEMAY CHOU: Sure, yeah. Sure, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: –does that mean it’s not going to survive out here?

SEEMAY CHOU: Ah, like whether it could proliferate–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

SEEMAY CHOU: –in the population? Yeah. Unless it came along, a female and a male, and they magically found an animal to feed and mate on together, it’s pretty unlikely that it would proliferate.

IRA FLATOW: I know there are ticks that may have a meat allergy.

SEEMAY CHOU: Um.

IRA FLATOW: How does that happen?

SEEMAY CHOU: Yeah. I’m from Texas. So I get a lot of questions about this from my friends from Texas. We don’t know what’s causing this in terms of whether there is a microbe responsible.

This actually ends up being an allergy against the sugar modification that somehow is now associated with red meat. And so there are a lot of different groups trying to look into this. Whether there could be something, we just don’t know.

The microbe may be in there that’s causing this allergic reaction or if it could be something related to the tick. But it’s restricted to a different type of tick from the genus Amblyomma. So it’s the Lone Star tick.

IRA FLATOW: Are you going to make a career out of studying ticks? I mean, you go on to a different arachnoid?

SEEMAY CHOU: You know, who knows? I mean, that’s the beauty of science research is that you never know where you’re headed.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much for taking time to this today.

SEEMAY CHOU: Thank you so much.

Seemay Chou is Assistant Professor of Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of California in San Francisco. And you can see a photo of Dr. Chou’s lab and all the ticks up there on our website at sciencefriday.com/ticks.

Charles Berqquist is our director; senior producer, Christopher Intagliata. And our producers are Alexa Lim, Christie Taylor, and Katie Feather. And we had technical engineering help today from Kevin Wolfe, Lisa Gosselin, and Rich Kim. B.J. Leiderman composed our theme music. And our thanks to audio engineer Jim Bennett, Tiffany Mitchell, and all the great folks here at KQED for welcoming us into their studios today.

And also on Science Friday VoxPop app, we’re asking you to talk about astronaut Catherine Sullivan. We’re going to be talking with her next week. What have you always wanted to know about living and working in space? Tell us on the box VoxPop app. And then we’ll play it. And Catherine Sullivan might answer your question.

You know, we play them every week. And next week we’re asking you, what have you always wanted to know about living and working in space? Science Friday VoxPop app, wherever you get your apps. I’m Ira Flatow in San Francisco.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.