Massive Iceberg Breaks Off Antarctica, Revealing Wonders Below

16:51 minutes

In January, an iceberg the size of Chicago splintered off from the Antarctic Peninsula and drifted away in the Bellingshausen Sea.

As luck would have it, a team of scientists was nearby on a research vessel, and they seized the chance to see what was lurking on the seafloor beneath that iceberg—a place that had long been covered, and nearly impossible to get to.

They found a stunning array of life, like octopuses, sea spiders, and crustaceans, as well as possible clues to the dynamics of ice sheets.

Host Ira Flatow talks with the expedition’s two chief scientists: Dr. Patricia Esquete, marine biologist at the University of Aveiro in Portugal, and Dr. Sasha Montelli, glaciologist and geophysicist at University College London.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Patricia Esquete is a marine biologist at the University of Aveiro in Aveiro, Portugal.

Dr. Sasha Montelli is a glaciologist and geophysicist at University College London in London, England.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. There’s an old saying. It’s better to be lucky than good. But what if you’re lucky and good? Well, here’s how that happened.

In January, an iceberg the size of Chicago splintered off from the Antarctic Peninsula and drifted away in the Bellingshausen Sea. As luck would have it, a team of scientists was nearby on a research vessel, and the scientists seized the chance to see what was lurking on the sea floor beneath that iceberg, a place that had long been covered and nearly impossible to reach. They found a stunning array of life. Octopuses, sea spiders, crustaceans, and possible clues into the dynamics of ice sheets.

Joining me are the expedition’s two chief scientists. Dr. Patricia Esquete is a marine biologist at the University of Aveiro in Portugal. Dr. Sasha Montelli, glaciologist and geophysicist at University College London. Welcome both of you to Science Friday.

SASHA MONTELLI: Thank you for having us.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Sasha, you happened to be in the right place at the right time. Tell us about what your original mission was.

SASHA MONTELLI: Our science agenda was merged from two different proposals. One was Patricia’s. Another was mine. Patricia’s agenda was mostly biological investigations of this very poorly investigated areas of Antarctic Peninsula. And my team was aiming to discern the ice ocean interactions, the melting of ice on a range of timescales from tens of thousands of years to industrial era to the present.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us how you happened to be at the right place at the right time.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: Yeah, we had this plan of researching the sea floor of the whole Bellinghausen Sea, pretty much. And because of the ice condition, the ice coverage this year, there was way more ice than we expected at the beginning. We found ourselves restricted to the wrong entrance, which is an area that is limited by three ice shelves and some islands. To put it really well, we were lucky and we were prepared. We were exploring very inaccessible areas, and we were exploring unexplored areas. So we were very much prepared to explore a newly exposed area at the moment.

IRA FLATOW: Now, let me just quote Louis Pasteur, who said luck prefers the prepared mind. So you were really prepared. What went through your mind when you saw that the iceberg had capped off?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: Well, there was a really amazing moment. And the first thing that crosses your mind is we have to go there. Yeah, there was no doubt. We just look at each other and said, let’s go there right now.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So now you were fortunate enough to study the sea floor under an ice sheet. Why is it so hard to do that?

SASHA MONTELLI: You can imagine, well, ice shelves are continuations of ice sheet that is grounded. So interior of Antarctic ice sheet, you can find ice that is 12,000 meter thick, extremely thick. And then you can imagine ice sheet flowing towards its edges and thinning like a pile of honey, viscous honey. And then as it flows towards the margins, towards the sea, it’s thins and flows into the water, ocean water. And it thins to the extent that it becomes buoyant and reaches flotation point.

So then these floating ice shelves, which are essentially fringes of Antarctic ice sheet that is grounded, they can extend over the area size of France. And they are hundreds of meters thick. So it’s extremely difficult to get underneath there. It’s perhaps one of the most remote areas in the world in terms of subsurface, the sea floor. Yeah.

So the only way to do a comprehensive study like we did, interdisciplinary, comprehensive study, is to, if you’re lucky enough that the ice shelf rapidly disintegrates or carves off huge iceberg. Because otherwise, it’s just impossible. Simply because of this remotely operated vehicle are attached by cable to a vessel.

And so cables just even if they were willing to deploy those under an ice shelf, just cables wouldn’t be long enough to go as far as 20 kilometers, say, beyond the carving front. So yeah, so ice shelves are just among the most remote and hostile areas. And as simple as that.

IRA FLATOW: Oh. OK, so you’re motoring on over to this wonderful piece of real estate underwater of this part of the sea floor that has not been exposed before. What do you expect to see, Sasha, and what did you actually see?

SASHA MONTELLI: So it was embracing the unknown, really. Because again, nobody really has done much work under an ice shelf. There were some studies that were fairly limited in scope and in geographical coverage, just because they usually would drill a borehole through an ice shelf, and then they would put a fairly small drone through the borehole. And then they would be able to see something. We knew that there is life under the ice shelf. So that was not perhaps a surprise that we saw life itself. But it was extremely surprising the degree to which life was thriving, diverse, colorful. So that was the major surprise for us.

IRA FLATOW: Patricia, tell me a bit about that. So you drop this camera. It goes down to the sea floor. Paint me a word picture of what you’re seeing as the camera is lowering.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: So actually, we had a remotely operated vehicle, an ROV, which is not just a camera. It’s just, factually, it’s a robot that can go thousands of meters under the surface. And it not only has cameras. It also has arms and has capacity of samples.

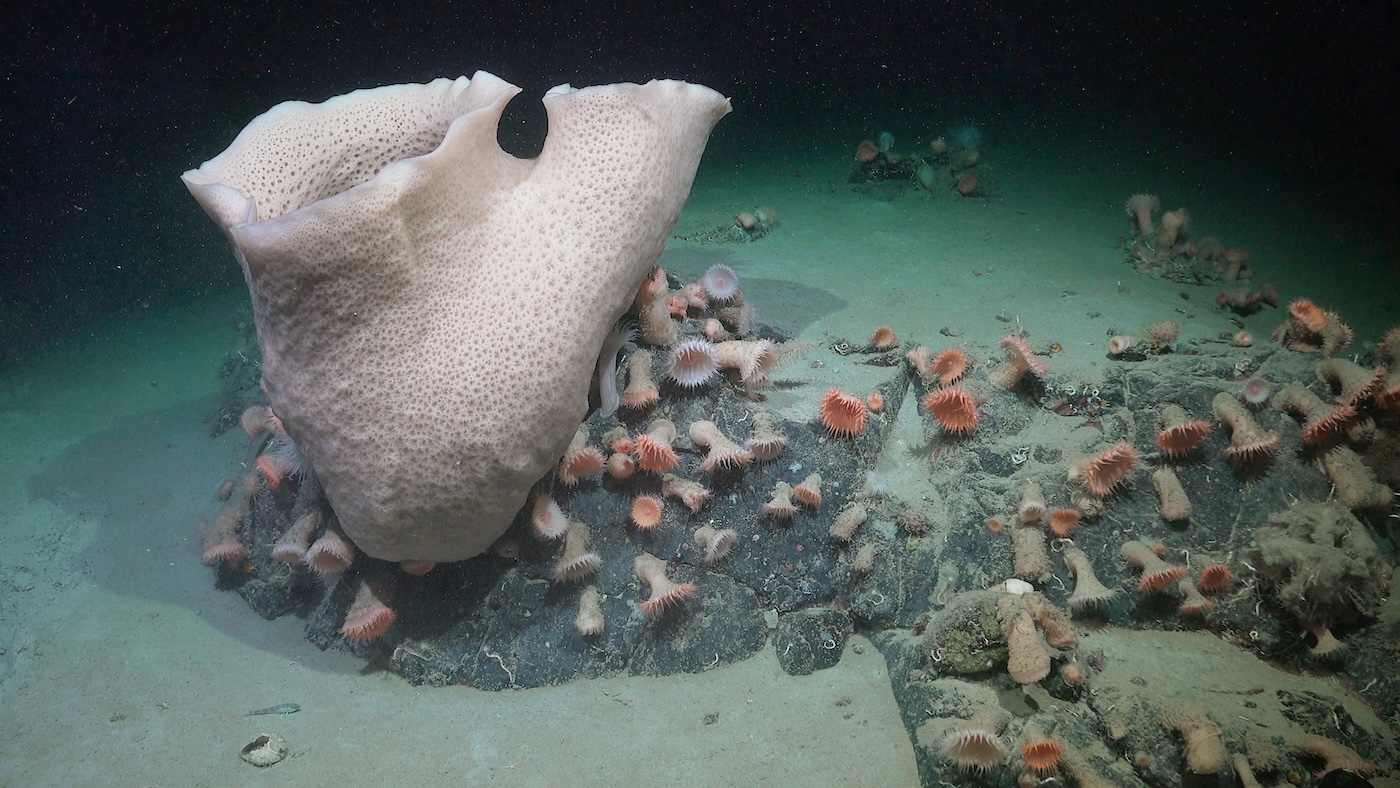

So the first thing we saw, I remember it very well because it was quite amazing for us. The first thing we saw was a huge, massive barrel sponge with a crab on it and other critters around and hanging on the sponge. And then another sponge and another one. And all of them were not only huge, but also had other species living on top of them.

That’s all really quite amazing, because that tells you that the ecosystem is very mature and well established, because you have long lived species like the sponges and also several species living on top of it. So you have high biodiversity. You have species interactions. You have biomass. And that tells you this is a very well established and mature ecosystem. And that was pretty amazing.

As Sasha was saying, we knew that there would be some life under the ice shelf. But because of the amount of ice on top of it, it cannot be fed by photosynthesis happening in the surface. That will be the normal setting. The food needs to come from somewhere else.

IRA FLATOW: So where did the food come from? How did it get its food if it wasn’t raining down on it for all those years?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: That’s one of the big questions, and that’s something that we still need to study with more detail. We need to– and this next step will be to understand how that ecosystem functions, where the food comes from. It’s certainly through the currents or bilateral transport instead of vertical transport. But where exactly is it coming from and how does something that we need to keep studying and figure out?

IRA FLATOW: So is that ecosystem, that diversity of life you saw down there, is it similar or different to other parts of the Antarctic sea floor?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: It was pretty similar. And that’s one of the things that actually makes it surprising and amazing is that it’s really very similar, at least to other ecosystem that we had been studying nearby in the days before and the weeks before. So that means that the conditions can be very similar than in other more exposed areas.

IRA FLATOW: So what other critters did you see down there? Did you have a favorite?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: I have several favorites. I have two favorites.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about them. Yeah.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: One of my favorites is an isopod. It’s more like a shrimp, but you need to imagine it as a flat stream that kind of crawls on the sand. I like that particular one, because I’m a taxonomist and I study these kind of animals. And one of them was probably very likely a new species.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: So I not only liked it, but also will get to name that species.

IRA FLATOW: Who are you going to name it after.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: I don’t know yet.

IRA FLATOW: Yourself?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: No. That’s something that we never do. [LAUGHS]

SASHA MONTELLI: I’m a glaciologist, so I’m obviously not that competent in species. But I can say that to me, the major highlight was when we descended to see this outcrop of black rock, the wall, almost vertical wall, layers of strata. But on top of it, there was almost like hanging gardens of corals of different colors. If you imagine very gentle, pastel colored sunset. So from purple to orange to white. And that was the first thing we saw when one of the dives. And to see it as a first thing, it was just absolutely stunning and exhilarating.

IRA FLATOW: Well, as a geologist, I think most of the public doesn’t realize there’s a whole continent under that ice. There’s a lot of rocks there.

SASHA MONTELLI: Yes, yes. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Describe what– is the floor flat, or has it got mountains and ridges and things there? Because you’re, what, 1,300 meters down.

SASHA MONTELLI: It is extremely rugged. Yeah. So the amplitude, you can even think of it as a mountain range under an ice shelf. So the shallowest bit we encountered was as shallow as 100 meters, if not shallower, actually. At some point, the captain actually had to urgently turn the ship around, because every second, basically, is being reduced by 10 meters. So they clearly go into some extremely shallow areas.

But then at the same time, right adjacent to it, so next door, in 10 kilometers or a few miles away, the depth was as high as 1,300 meters. So the huge range of depth. You can imagine– Yosemite probably could be a good example of that. So if you look at the Yosemite, very, very, very sharp cliff. Very high amplitude. So now put it under water and put ice shelf on top of that. And so that’s kind of the landscape that you see there.

IRA FLATOW: So did you actually discover something that was not charted before?

SASHA MONTELLI: Yes, this was the first map ever in that area. So that’s obviously quite exciting. And this map, it’s not just for the sake of mapping. It’s not mapping for the sake of mapping. These maps, really, these shapes that are preserved on the sea floor, they really tell us something about the history of ice.

Not only in sediment, because sediment obviously like an ice core, sediment cores preserve the history of climate and history of environmental change in the area, but also the shapes of the sea floor. We see some features, like elongated stripes that tell us something about the history and configuration of flow of ice, which is extremely important in terms of providing longer term context into behavior of ice, and into the changes that we see from the satellite era and observable record.

IRA FLATOW: Patricia, how do you think the ecosystem and all the corals and the jellies and all those animals you saw down there, how are they going to fare with no ice above them after they’ve had it for lord knows how many, maybe thousands of years, right?

PATRICIA ESQUETE: That’s actually another very, very good question and also very important to investigate. Why? Because first of all, whatever is feeding the ecosystem is doing it very effectively. Because as we say, there’s a lot of biodiversity, a lot of biomass, a lot of life, beautiful life. Because of the climate change, we know that Antarctica is losing ice year by year, and ice shelves are collapsing. And it will be happening more frequently.

IRA FLATOW: So yeah, there’s some urgency then to what you’re doing.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: There is. It’s going to be very important to actually understand how ecosystems, not only directly under the ice, but also in the neighborhood, will react and will be able to cope with or will change or not with all this ice melting.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, yeah. Do you plan on going back, both of you? Sasha?

SASHA MONTELLI: That would be lovely. I think it also provides the opportunity for us too, because we have, as we just discussed recently, we have this really nice time 0 event. And we know exactly where we acquired the data to very high precision. So we can go back there at exactly the same locations to exactly the same sponge, individual sponge, and see how they’ve changed over time.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: And also to the same corals, which is also very interesting and very important, because the corals, for instance, they depend a lot on the current, on the current regime. So being able to go back exactly to that point in which all those corals, all those range of colors and species and interactions were happening and seeing whether it changed or not or how is going to be very important. We definitely need to go back.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I’ve been to Antarctica. I know how exciting it is to be there. They say we know more about the surface of the moon than we know about what’s under the bottom of the ocean. You must feel like explorers. Something brand new that you’ve discovered.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: We are explorers, as I was saying. Really our aim was to study and map and sample areas that have never been sampled or mapped before. So yeah, we were exploring, and we just got to explore something a bit more special than we expected.

IRA FLATOW: Here in the United States, we’re fearful of research being cut back by the new administration. You folks are not part of the American science community, so you can continue to do your work. Who’s funding the work that you’re doing?

SASHA MONTELLI: The philanthropic organization called Schmidt Ocean Institute, which is based in the United States, ironically. So I guess it’s quite sad the funding costs, because ultimately I think there are no borders in understanding the world around us. I think that this limitation of a major, major science power is just limitation to the whole world, really, in terms of science. So I think the world around us needs to be studied more.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to thank you both for taking time to describe this terrific work that you’re involved in. And good luck to you, and I wish you pleasant sailing next time you go back.

SASHA MONTELLI: Thank you so much.

PATRICIA ESQUETE: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Dr. Sasha Montelli is a glaciologist and geophysicist at University College in London. Dr. Patricia Esquete is a marine biologist at the University of Aveiro in Portugal.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.