The Reef Is Quiet. Too Quiet.

6:43 minutes

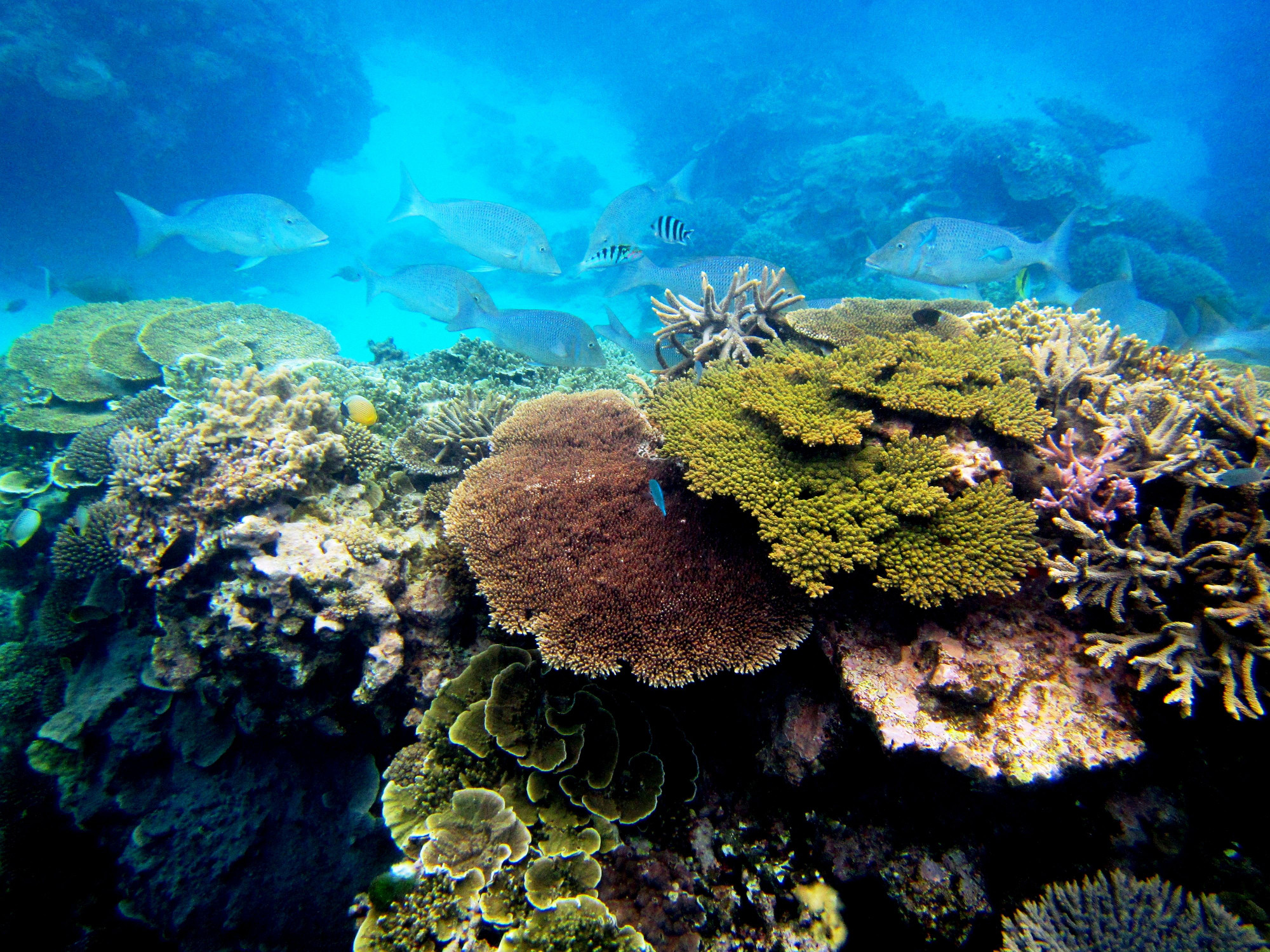

A vacation by the seaside might seem relaxing. But beneath the waves, there’s a lot going on—with marine organisms fighting, feeding, mating, and more. On a healthy coral reef, all that activity adds up to a surprising chorus of clicks and pops.

But in a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers monitoring one part of the Great Barrier Reef document a dramatic dropoff in undersea sound levels. The scientists compared recordings from 2012 and 2016, and found that the 2016 reef was about 15 decibels quieter than it had been just four years before. The quiet is an indication that not all is well with the reef ecosystem, they say—and the quieter reef lacks some of the auditory cues that species need to survive.

[SciFri Trivia is back in Brooklyn on 5/9! Let the brainiest of the brains win.]

Rachel Feltman, science editor at Popular Science, joins Ira to talk about the quiet reef and other stories from science this week, including Hawaiian sunscreen regulations, an upcoming Mars launch, and more.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A seaside vacation might seem calm and relaxing, right? But under the waves, there’s a lot going on under there. A healthy coral reef is a surprisingly noisy place. A new study finds that when a reef is in trouble, it gets too quiet. Joining me to talk about that and other selected short subjects in science is Rachel Feltman, science editor at Popular Science. Welcome back–

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: –as I stumble through the introduction. Nice to have you here to bring some cohesion to this. We have some recordings that the researchers have captured about a reef, OK? And you’ve helped out with this. So let’s listen to our first recording.

[CRACKLING]

Sounds like my eggs in the morning. What is that?

RACHEL FELTMAN: So those are the sounds of all the little clicks, and whistles, and pops that fish make to each other. We think of fish as being quiet, but just because we don’t speak fish. And shrimp are clacking their little legs. So a healthy reef is like an urban center in the ocean. And a healthy reef is full of all of these noises.

And so researchers were curious about how that’s changing, now that coral reef are suffering. And they compared noises a few years apart, basically looking at before a few major bleaching events, which is where the algae that are symbiotic with coral die, leaving the coral pretty much helpless and dead. So that recording with all the pops and clicks was a healthy reef.

IRA FLATOW: That was a few years ago that was recorded. And so if we were to listen to one now, we would not hear at the same volume going on.

RACHEL FELTMAN: They found it’s about 15 decibels quieter.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a lot, actually.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. And what’s more disturbing is that then made– did experiments with fish larvae to see if they were more or less attracted to– which recording they found more attractive. And they found that fish are actually less likely to want to go to a quiet reef, which kind of makes sense.

It seems like a pretty dead neighborhood. So unfortunately, it indicates there’s kind of a negative feedback loop that we have these bleaching events, because of warmer water, pollution, industrialization. And then that actually makes animals less likely to try to habitate the reef, which further contributes to its destruction.

And it’s just a really important reminder that it’s not too late to save our coral reefs and to save these ocean ecosystems. But we really do have to start fighting carbon emissions, other influences of climate change. We have to stop polluting the ocean. We have to actually put in the work to protect the coral, or it is going to be too late pretty soon.

IRA FLATOW: You’re preaching to the choir here. But there’s other coral news that Hawaii is banning some popular sunscreen.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. So oxybenzone and octinoxate, which are two chemicals that are in basically every chemical sunscreen. So a sunscreen is either chemical, which means you absorb chemicals that help protect you from the sun’s rays, or it’s mineral, which means that it creates a physical barrier like zinc to protect you from the sun.

And so most sunscreens are chemical, because they tend to work better. And most of them have these chemicals. There is some research that these chemicals are very dangerous to coral, that they keep them from photosynthesizing properly, that they’re toxic to their DNA.

And there’s also research that they get into the waterways, basically anywhere where you’re wearing sunscreen and you shower. The stuff is going to end up in the ocean. So it’s not even a question of whether you’re putting it on before you go to a coral reef. So Hawaii has been trying to ban them for a while, and they just– now, it’s official.

The governor signed it on Tuesday, I believe, that by 2021, they will not be selling sunscreens that contain these chemicals, which isn’t a bad thing. It is true that the research we have– even though there should be more studies on it, the research we have indicates these chemicals are not good for reefs. So we want to avoid them.

Unfortunately, there are only a couple mineral sunscreens that have good Consumer Reports scores. Mineral sunscreens tend to not provide the SPF protection they say they do. So consumers do it to be careful to make sure they are continuing to protect themselves from sun damage.

And the other thing is that some people feel this is kind of a feel-good measure. It’s true that it’s better to not expose reefs to this. But it’s kind of a drop in the bucket, compared to the warming water we have because of climate change.

IRA FLATOW: The acidification in the water.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Construction near coast and also, just the fact that people are visiting reefs. There isn’t really a healthy way to go visit a coral reef. So if you really care about them, you shouldn’t go snorkeling there.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. They step on them. I know. I’ve been a scuba diver. And people just step right on the reefs. They don’t care. It’s awful.

RACHEL FELTMAN: So as tough as it is, we probably should protect these reefs every way we can at all levels of policy, including lowering our carbon emissions. And we also probably shouldn’t visit them. Laypeople should not be going snorkeling at reefs.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Finally, you have a story about an endangered albatross.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Tell us about it.

RACHEL FELTMAN: So I think this is a great story. So there are these short-tailed albatross. They’re the most endangered albatross species in the Pacific. And they are mostly– there are about 4,200 of them, mostly around islands near Japan.

But they occasionally show up at this reserve called Midway, which is technically part of Hawaii. And there was this one named George. He was 15 before he found a mate, Geraldine. And they seemed to have an egg. And so that made– everybody would be really excited.

They thought– I think it would have been the fourth short-tailed bird to hatch in the US in known history. But when the egg hatched, it was not a short-tailed albatross. It was a black-footed albatross, which is another species.

IRA FLATOW: Disappointment all around?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, not quite. I mean, it’s true that they would have loved to see short-tailed birds reproducing on this island. But apparently, albatross are pretty bad at having eggs successfully and raising chicks successfully. So the fact that George and Geraldine are practicing on this adopted egg could still help conservation efforts, by making them more likely to successfully raise a chick next year.

IRA FLATOW: Parenting– it’s tough. Thank you, Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman is science editor at Popular Science.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.