The Recipe for California’s Wildfires? A Wet Winter And A Sweltering Summer

11:51 minutes

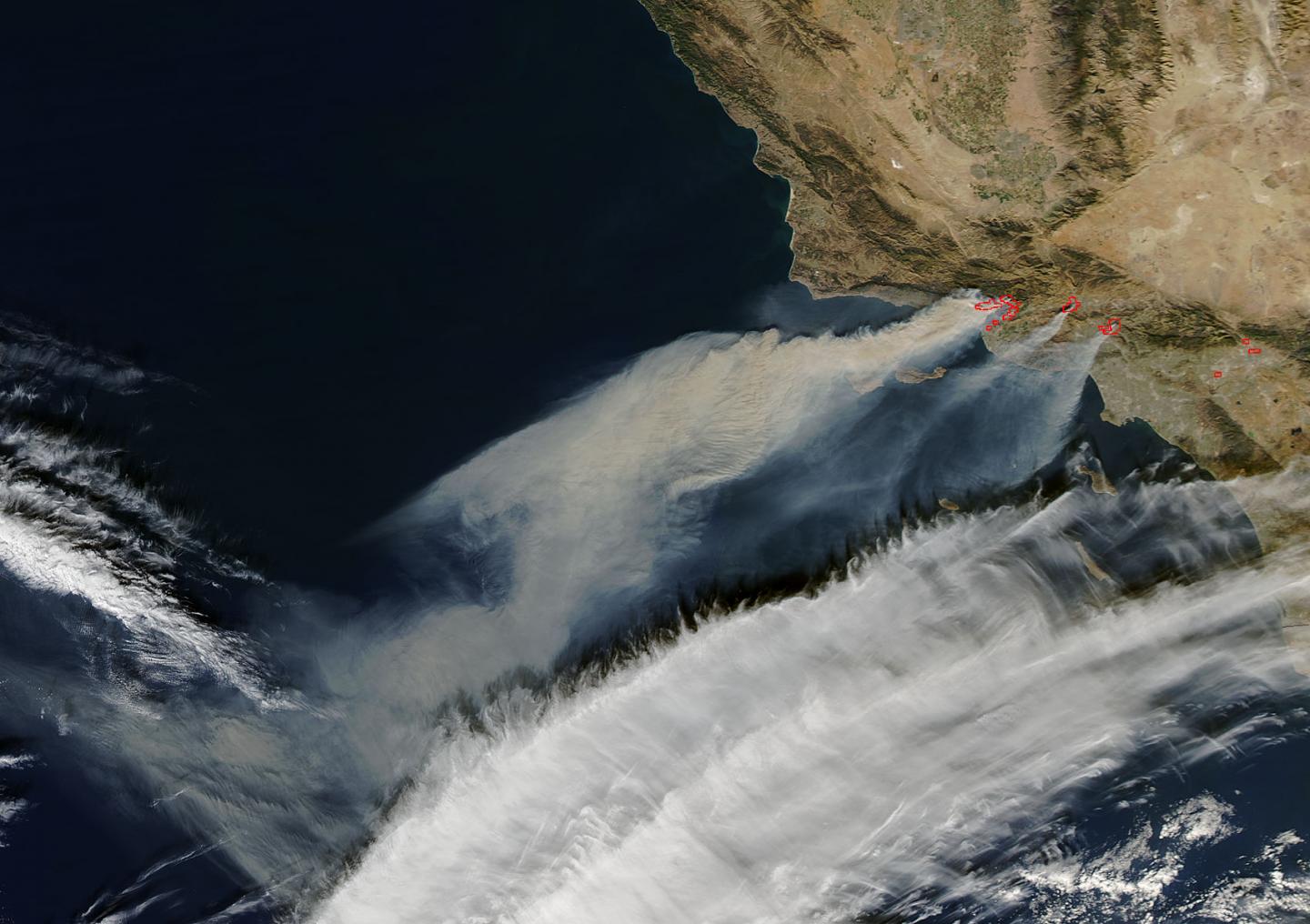

Southern California’s cities are under siege by out-of-control wildfires ripping through hillsides and housing developments. The blazes in Los Angeles and Ventura counties have forced more than 200,000 people from their homes, destroyed hundreds of buildings, and threatened thousands more. The current fires, along with the catastrophic wildfires earlier this year in Sonoma, add up to make 2017 California’s worst year on record for wildfire.

Hugh Safford, a regional ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region, talks about the ingredients that triggered this year’s devastating wildfire season up and down the state—and discusses why restoring native chaparral will be important after the burns.

And Joe Cahill, a botanist and executive director of the Ventura Botanical Gardens, says the chaparral scrublands in the garden have “burned totally to the ground.” He talks about the garden’s destruction in the Thomas fire, and whether some fire-adapted species may be able to survive.

View photos of before and after the wildfires ripped through the Gardens below.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. This week, Southern California finally, or rather and suddenly finds itself under siege by multiple wildfires spread by searing Santa Ana winds. And videos of this Skirball fire in Los Angeles showed an apocalyptic fiery commute along the 405 freeway as smoke filled the other parts of the city with gray skies and an acrid smell.

A bit further north, in Ventura, the biggest blaze, the Thomas fire, has now consumed more than 130,000 acres. It forced the closure of the 101 freeway. It has destroyed over 400 buildings, and it threatens thousands more. New evacuations are now in place, and President Trump has declared a state of emergency. And that will bring a lot of federal aid to the state and allow coordination with the Governor Jerry Brown of California.

We’re going to talk about why California has suffered so many devastating fires this year, up and down the state, in just a little bit. But first, I want to talk about one of the natural jewels ravaged by the Ventura area fire, and that is the Ventura Botanical Gardens. It was once rich in shrub-covered hillsides, exotic plants from South Africa and Chile, along with some Californian natives, and by now much of that garden has been charred to the ground.

And if your friends or your family have been affected by the fires, we want to hear from you. Call in and tell us your story. Our number is 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK. You can tweet us @scifri, but let me first talk to Joe Cahill, a botanist and the executive director of the garden, and he joins me now. Welcome to Science Friday, Joe.

JOE CAHILL: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: People always talk about devastations of homes and buildings, but we never talk about what it has done to a botanical garden. Give us an idea of what’s left of your garden.

JOE CAHILL: Well, there’s very little vegetation left. It kind of looks like a picture of the surface of the moon, except the Ventura Botanic Gardens is a coastal hillside that’s about 110 acres. And in recent years, we’ve developed garden and trails on about 20 of those acres. The area immediately surrounding that hillside is dense urban area, the downtown and other neighborhoods.

So in recent history, when other fires have started, they’ve been suppressed immediately because of the proximity to all these buildings. The last moderate fire was in 1970. So we’ve had about 50 years of plant growth on the hillsides, and a lot of dead plant material. So that’s part, that kind of fuel in the plant material is really what made this so intense and devastating.

IRA FLATOW: Now, you specialized in Mediterranean climate plants. Are some of those plants adapted to fire? Could they grow back? What’s the future look like?

JOE CAHILL: Yes. The areas that we planted, we had cleared brush, and our plants were still kind of moderate and small in size. So those areas actually fared better than the areas that had the dense brush. And we’re very hopeful that many of those plants will regrow, because the Mediterranean climate regions of the world, the plants are adapted to periodic fire.

The exception might be Chile. The plants from central Chile, although they have the same climate as Ventura, natural fire is much rarer there. Because lightning is rare, and there’s more fog. So It’ll be interesting to see how our Chilean garden responds to this fire.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting.

JOE CAHILL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Joe, I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today, and good luck with regrowing your garden. Joe Cahill is a botanist and executive director of the Ventura Botanical Gardens. And Joe snapped some amazing photos of the destruction for us, and you can see those at sciencefriday.com/wildfires.

So what were the ingredients that added up to make this such a catastrophic fire year in California? Just months after northern California burned in the Tubbs fire, now the south land is ablaze. Hugh Stafford has seen some of these fires firsthand. He’s a regional ecologist for the Forest Services, Pacific Southwest Region in Vallejo, California. Welcome back, Hugh.

HUGH STAFFORD: Thanks. Nice to be back, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about what is the cause of these things? You stopped by a few of the fires yesterday. What did you see?

HUGH STAFFORD: Yeah. We didn’t get a chance really to get on it, to any of the landscapes. There’s active fire management going on. So we stayed well away, but we actually had to put our trip off, down here with some Spanish colleagues, Because the area we were going to be meeting in and the area where we had a workshop were both under evacuation orders.

So we stopped and had the chance to observe the rye and the creek fires, and at that point they both left the freeways. The freeways were open. And I think this morning, the rye fire’s largely contained and most of the evacuations have been lifted there, luckily.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I said earlier that this has been an exceptionally bad year for a fire in California. As I mentioned earlier this year, with the Tubbs fire up north and now with half a dozen fires burning in Southern California. Is there a connection? What’s going on here?

HUGH STAFFORD: Yeah, no, certainly there is, and with the way that fires work is they’re driven– particularly the ignition part of the fire– is driven largely by the presence of fuels. Fine fuels in particular, when those encounter an ignition, and we had a bumper crop for fine fuels this year, which are called by many people grass and some new growth on shrubs. We had a very, very wet winter in 2016 and 2017. For a lot of the state it was a record, although here in the southlands, it wasn’t quite so wet. And then that was followed by the hottest summer that any of us can remember.

And we’re now in a situation where the arrival of the winter rains has been delayed. It hasn’t happened, and it’s important to note that October and November are really serious fire months, particularly south of the Bay Area and the South of the Tehachapi Mountains. And we have big fires this time of year, all the time, but this particular year, we’re in December now, rain hasn’t come, and this Santa Ana event is notable. There have been very strong winds, and they just– even though the winds are calmer today– they just extended the event out until Sunday, at least, it sounds like.

IRA FLATOW: And there was a study out this week in the journal Nature Communications that predicts California will only get drier as sea ice disappears in the Arctic. So are we looking at a future filled with even more fires in California?

HUGH STAFFORD: No, that’s alarming. Yeah, I think that any of us who study this, and even people who don’t, understand that with warming temperatures– you’re seeing the same effects that, for example, warming ocean temperatures have on the probability of damaging hurricanes. They don’t drive any single hurricane, but they increase the probability that that might occur, and that’s what we’re seeing. It’s just the dry fuels that we’re seeing at the end of the year, with the humans expanding more and more into wildlands, and more and more of these kinds of aseasonal ignitions. I don’t think there’s any question that we’re going to be looking at more of this in the future.

IRA FLATOW: I know you’re talking to me right now from a workshop on restoring chaparral landscapes after fires. Give us an idea why that is important.

HUGH STAFFORD: Yeah, so chaparral ecosystems have been relatively understudied, with respect to the effects of multiple fires on them. And they cover large landscapes in California, a lot of the Central Coast, and a whole lot of Southern California, and indeed the four national forests down here– maybe misnamed– they’re really largely scrublands. And the ecosystems are somewhat under-valued.

People like trees. They like shade. They like cool temperatures, but but chaparral supports a surprising amount of carbon. It’s very important to water infiltration, to water recharge in the ground water, to supporting water runoff. And to keeping sediment on the hills here, which ends up in people’s homes and on highways, if there isn’t vegetation on the landscape, and there is a lot of biodiversity. San Diego County is the most biodiverse county in the US.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Let’s go to the phones. Stephanie in Ventura, she’s calling from California. Hi. Welcome.

STEPHANIE: Hi. Thank you for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

STEPHANIE: Well, I was just calling, living in the city of Ventura, it’s just been a little anxious and just scary. The smoke is just sitting here in the city, and I work outside. It’s hard to breathe, and so I just wanted to share my thoughts and prayers for the people of the city of Ventura.

IRA FLATOW: So tell you are you feeling anxious about the smoke inhalation and might be harming you?

STEPHANIE: Certainly. I work outside. I have a mask on, but it doesn’t seem to be doing much. I have a dull headache that’s been around for a couple of days, and it’s scary. You can see it in the air.

IRA FLATOW: All right, thanks for taking time, good luck to you.

STEPHANIE: Thank you so much. You have a good one.

IRA FLATOW: Hugh? Lot of folks afraid.

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, go ahead.

HUGH STAFFORD: Smoke is not good stuff, and I just wanted to say that we are actually meeting, as an alternate meeting spot, today at the Rancho Santa Ana Botanical Garden. And so we really feel the pain of the Ventura Garden, and we wanted to send our condolences and our best wishes to them but to everyone around them as well. And I know, people in our meeting here have seen the– UC Santa Barbara cancel classes today, and I know a lot of schools along the coast have canceled classes, because the air quality is so bad.

IRA FLATOW: Is it possible we’re looking at a future where we might start to see big urban fires, fires that start out there in the wildlands, in the hills, but start cutting through the urban core?

HUGH STAFFORD: Well, it depends on how you define urban. I think that if you’re referring to suburban development, that’s not new. This has been going on for a while. I think if you look back, I think some classic examples are 2003 and 2007, when Southern California burned 800,000 acres almost in 03′ and almost a million acres on its own, in 2007. So much bigger fire years than this year, and thousands and thousands of homes burned down. And the answer is absolutely yes, that with winds in close proximity of homes, very often homes that haven’t been designed to be really in this kind of fire prone habitat. Yeah, I think you’re looking at this kind of thing in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Is there enough water to put out? Are these fires just going to burn themselves out?

HUGH STAFFORD: What is likely going to happen, Ira, is the weather will finally change at some point, and indeed today, I believe I can see the winds have calmed, and I think there’s going to be a little bit of a Maritime flow. What that will do is that will reverse the wind direction, and it will come in as a much moister layer. And that will help in fire behavior, as long as it’s not too strong, and this is typically what happens.

These winds come from the east to the west. They drive things towards or into the ocean. Then, they reverse when the system changes, and the Maritime winds come onshore, and then we get control of them. But in some instances, yeah, they do actually end up in places where there’s not much more to burn.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re going to hope for your famous marine layer to come in?

HUGH STAFFORD: That is exactly what we’re hoping for. That’s exactly right.

IRA FLATOW: Hugh Stafford, Regional Ecologist for the Fire Service Pacific Southwest Region in Vallejo California. Thank you for joining me today.

HUGH STAFFORD: Thank you.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.