The Real Science In The New Ghostbusters

16:24 minutes

In a film about the paranormal, what possible role could science play behind the scenes? As it turns out, several scientists were involved in the creation of the new Ghostbusters film.

Physicists James Maxwell, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s Jefferson Lab, and Lindley Winslow, an assistant professor of physics at MIT, both got the call to bring their expertise to the big screen.

Maxwell had coil magnets from the polarizer in his lab used as set props and both scientists were consulted on set design.

“They needed to understand what the lab looked like,” Winslow says. “There’s junk all over the place. [When they saw] my lab, [it] was really filled with junk … and so actually they took two boxes of junk from my lab, and instead of getting recycled, it went to the Ghostbusters set. So I thought that was pretty cool — my junk made it on camera.

[The future is coming… ‘Soonish.’]

Winslow and Maxwell say they also spent time thinking about the scientific properties of ghosts.

“Obviously they’re neutrinos,” Winslow says. “They go through anything, but if you get them really mad, they’d blow up stars. And so I think there’s a good comparison to the ghost in Ghostbusters.”

Maxwell put his theories about ghosts into building prop weapons to fight them.

“We think that the laws of physics apply everywhere all the time, but these ghosts clearly change these rules,” Maxwell says. “They’re not everywhere all the time, so what in Ghostbusters you call these manifestations of ghosts on our planet, existence, or something I saw as like an isolated visible phenomenon in which there’s this significant coupling between standard model particles and this spectral other stuff. And so with this idea, I set out to try to spec out all the props that they showed me and build a cohesive framework of what is the science of ghost busting and how would you actually attack these things.”

Maxwell is also responsible for coming up with the Ghostbusters’ spectral-fighting synchotron, which is based on a fan’s recreation of the original proton pack.

“I took the cyclotron idea and I tried to expand on it and tried to make it a little more legitimate,” Maxwell says. “We’re going to use a synchrotron. Where do you get the protons? You have to have some kind of proton source — maybe an electron, cyclotron residents like plasma source. You feed that into a miniature super-conducting proton synchrotron and you have to tune the beams to hear the beam and put in a wand that you can then point at the ghosts.”

[Six bestselling authors share their favorite ‘other worlds.’]

Both Maxwell and Winslow say that, amongst all the science fiction comedy, there was a lot of real-life science in the film. The equations on Kristen Wiig’s character’s whiteboard, for instance? Winslow made sure they were accurate. And the science labs in Ghostbusters were more similar to real-life labs than many movie portrayals.

“In some movies there are these like pristine [labs] — lots of stainless steel and acrylic and everything is put away in their drawers,” Winslow says. “Other movies there’s junk all over the place. Unfortunately the latter is more like what our labs were.”

Maxwell agrees.

“We got to step into these sets that were just so amazingly realistic and…gritty,” Maxwell says. “And it’s real because scientists are not necessarily clean people all the time…it felt like, you know, like totally legitimate science that leaked into this paranormal comedy somehow.”

—Elizabeth Shockman (originally published on PRI.org)

James Maxwell is a researcher at Jefferson Lab in Newport News, Virginia.

Lindley Winslow is an assistant professor of physics at MIT in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

[MUSIC – “GHOSTBUSTERS THEME SONG”]

That of course, is the new theme for a new reboot of an old favorite movie. Of course it’s Ghostbusters, which hit theaters last night. And in it a new lineup of joke cracking women, including a physicist and an engineer, fight the same kinds of spirits the original crew battled 30 years ago. I can’t believe it. I’ll leave you to decide whether to see it. I think I’m going to go see it.

Meanwhile, in a movie where ghosts walk among us real enough to battle with the help of a proton pack, where does the science come in?

JILLIAN HOLTZMANN: I got some pretty cool stuff cooking up over here, if you want to just turn your head. I improves beam accuracy by adding a plasma shield to the RF discharge chamber. I have cryocooler to reduce helium boil-off. And to top it all off, we got a fricken faraday cage.

IRA FLATOW: Who doesn’t have a faraday cage these days? That was actress Kate McKinnon, who plays engineer Jillian Holtzman, and she got help from one of our guests with that dialogue, right down to the faraday cage. And both my guests helped make sure the proton packs and the Ghostbusters lab were realistic visions of particle physics, right down to the equations on the bulletin boards. Let me bring them on. Dr. James Maxwell, a staff scientist at the Department of Energy’s Jefferson Lab. He helped design the proton packs used in the movie, and the movie has a replica of his own lab instrumentation. It was all part of the set. Welcome to Science Friday.

JAMES MAXWELL: Hi Ira, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome, Doctor. Dr. Lindley Winslow, an assistant professor of physics at MIT. She made sure that all the equations you see were accurate and relevant to particle physics. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Winslow.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Thank you, it’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I got to ask how you both got involved. Dr. Winslow, you first. How did you both get involved in this project?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: So particle physics is a pretty small world. So I spent two years that UCLA, where I overlapped with David Saltzberg, who’s the science advisor for the Big Bang Theory. And so they went to him to say, who should we talk to in Boston? And they sent props and set dressing to me, and I tried to teach them what a particle physics lab should be like.

IRA FLATOW: And James?

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah, so when they came to Lindley, she gave them a tour of all the labs at the Lab for Nuclear Science. And one of the labs she showed them was my helium polarization lab. So they took a bunch of pictures and showed them to the director, Paul Feig. And he saw my lab and apparently pointed at it and said, give me that thing. And I guess I was in the background of these pictures. And I imagine he’s pointing at me and saying, give me that nerd. So they essentially just asked me to replicate my lab for the set, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: And did they do that with you, Lindley, also? Get some of your lab in there?

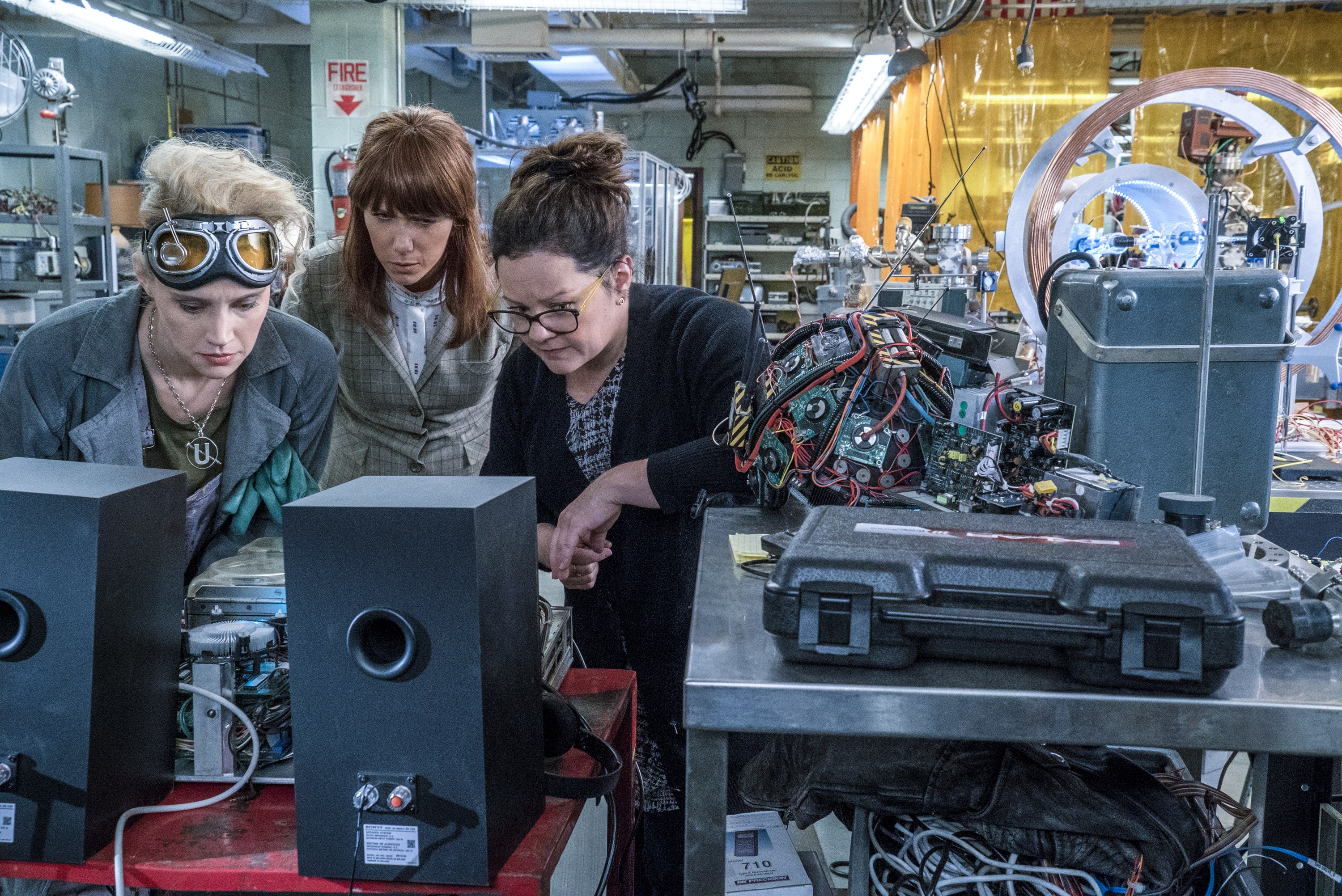

LINDLEY WINSLOW: No, they needed to understand what the lab looked like. And what apparently they heard from the director about my labs, he thought, well. Those labs are gritty and dirty. That’s exactly what I wanted. They were used to more like the acrylic and stainless steel that you often see in science fiction. Like no, no. Our labs are much more like Ghostbusters than like Star Trek.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I mean more like the original Ghostbusters, too. Now your apparatus led you both down a rabbit hole to giving even more assistance. James, tell us how much did you end up doing? What was your help? Besides having your lab there.

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah well, so I guess having my lab there meant I had to like produce machine drawings for them, and borrow some derelict equipment from the MIT Bates accelerator, and stuff like that. But then, if you watch the movie, you can actually see the big copper hoops of the Helmholtz coil magnets for my polarizer. But then when I was on the set, I actually got to chat with the actors. With Melissa McCarthy, and Kristen Wiig, and Kate McKinnon, and explain what my experiment was and how it worked. And then after that, Paul Feig actually asked me to diagram all these props with realistic terminology. And since this hardware is really pretty central to the movie, it led to a lot of other little bits of consulting on the script and such.

IRA FLATOW: Do you actually have your own proton pack?

JAMES MAXWELL: [LAUGHS] Yeah, I mean it’s like a prototype, I guess.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Lindley, the scientists of the original Ghostbusters were psychologists. I remember, you know, that little trick test that was being done there and with the cards. But in this movie, we have a physicist, we have an engineer in the mix. Is it cool to see someone like yourself on the big screen?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Yes. So Kristen Wiig’s character is actually an assistant professor, she’s supposed to be at Columbia. But I was very excited to see that in one trailer she was wearing an MIT sweatshirt. So as you can imagine, I really relate to a woman assistant professor at this point. And so one of the scenes that you actually see in the trailers, is her in front of this huge white board giving what I think is going to be her 10 year talk. And that was my big contribution to it, is exactly what went up on that board and how exactly nervous she should of giving it.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, 844-724-8255, if you’d like to join our discussion. Talking with James Maxwell and Lindley Winslow, scientists who are consulting on the new Ghostbusters. I also think it’s kind of cool that Lindley, you are a neutrino scientist. And aren’t neutrinos kind of the ghost particles of physics?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Actually, James and I were joking about this earlier. We were debating exactly what ghosts would be if they were real. And like obviously, they’re neutrinos. They go through anything, but if you get them really mad, they blow up stars. And so, I think there’s a good comparison to the ghosts in Ghostbusters.

IRA FLATOW: Did they know about that before they got you involved? That those were ghost particles?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: No, I think that’s a good happenstance. But nature likes happenstances often.

IRA FLATOW: So this movie isn’t The Martian, it isn’t Gravity, and yet you were a science consultant, James. How do you figure out where the real science fit into a story about fighting ghosts?

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah, I guess it’s a challenge. The first thing I had to think about, was to think critically. What could ghosts actually be? I mean, so Lindley says, maybe they’re neutrinos. To me, it’s weird. We think that the laws of physics apply everywhere all the time, but these ghosts clearly change these rules. They’re not everywhere all the time. So in Ghostbusters, you call these manifestations of ghosts on our plane of existence, or something. I saw it as like an isolated physical phenomenon, in which there’s this significant coupling between standard model particles and this spectral other stuff.

And so with this idea, I set out to try to spec out all the props that they showed me, and build kind of a cohesive framework of what is the science of ghost busting, and how would you actually attack these things.

IRA FLATOW: So did you make it believable? I mean, for science to actually explain how a ghost could appear?

JAMES MAXWELL: I mean, to a certain degree. I mean they’re ghosts, so maybe they’re not real. But what I wanted to put in the packs were realistic components. That if you sat down with schematics and you looked at them, you could go and look at every component I put on there, look it up on Wikipedia, and learn about some realistic tools that physicists use to study the universe.

IRA FLATOW: No dark energy or dark matter required here, for this.

JAMES MAXWELL: Well, might be. Might be

IRA FLATOW: Was there any point where you said– I know you can’t say cut, you’re not the director– say, wait a minute, you can’t say that. That’s just too far out, scientifically.

JAMES MAXWELL: No, no, I don’t think so. I mean it’s a comedy, right? So it’s just a lot of fun. So it’s let them have their fun, and then work in a little bit of legitimate science when you can.

IRA FLATOW: Now let’s talk about your proton pack a little bit. Yeah, how do you redesign a proton pack from what was different from Danny Aykroyd’s cyclotron, right? Isn’t that what he had on his back, something like that in the old movie?

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah, that’s exactly right. So Paul Feig, he sent me this schematic that a fan, I think, had made of the original proton pack, and said, hey, can you remake one of these for us? So I took the cyclotron idea and I tried to expand on it and tried to make it a little more legitimate, right?

So maybe we’re not going to use a cyclotron anymore. Now we’re going to use a synchrotron. Where do you get the protons? So you have to have some kind of proton source, maybe an electron cyclotron resonance-like plasma source. You feed that into a miniature superconducting proton synchrotron, and you have to tune the beam, steer the beam, and put it in a wand that you can then point at the ghosts.

IRA FLATOW: You still never cross the streams in this movie?

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah, don’t cross the streams. That critical.

IRA FLATOW: Lindley, you were responsible for the info in the equations we see in the film on a white board in the physics professor’s university, and then all over the Ghostbusters lab. How did you decide what needed to be there?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: So they were pretty tight with the script. I wasn’t allowed to read the whole thing, obviously, but they gave me one line, that she was trying to unify quantum mechanics and gravity, which is this great problem in physics now. So I thought about that and what she would say up in front of her colleagues.

And so what I came up with this is this theory SU5 that you see up there, which is a theory that was disproved by an experiment called Super-Kamiokande based on the life of the proton. And the background to this measurement was actually neutrinos. So I love this measurement. And so I’m like, that’s what she would put there. That would be the introduction to her work as an assistant professor. And so that’s what’s behind her.

IRA FLATOW: No string theory or anything like that.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: There’s a little string theory off in the corner, but the running joke of everything on the boards is me. And when I went on maternity leave, my colleague Janet Conrad took over, as a little, sort of, poking fun at string theorists who haven’t quite come up with something we can test yet. And so as an experimentalist, we like to keep poking at that.

IRA FLATOW: OK, so I’m a physicist. I’m going to see the movie. What am I going to see on those equations?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: So there’s a good Feynman diagram. There’s some actual experimental limits from Super-Kamiokande, and then the actual derivation of the life of the proton within this theory. So this is where James is one up on me. He’s actually seen the movie. I don’t know how many of the lab boards actually got up there, because there you see homages to my favorite experiments including my current experiment quarry, which is searching for a rare process called double beta decay. I’m hoping that made it up there, but I don’t know.

IRA FLATOW: You mentioned the science advisor to the Big Bang Theory, did you ever go back to him and say help, what should I put up on the board?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Well, David actually had taken me to a filming of the Big Bang Theory once, so I got to see how that worked. And I was like OK, I’ve gotten a little tutorial on what should go up there, and how to make your friends happy by putting their experiments up there.

IRA FLATOW: And so the set design was inspired, Lindley, by a tour through your lab and other physics labs. What is a physics lab? What is a Hollywood version? Central casting– what a physics lab supposed to look like?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: So I think it depends on which movie you’re in. In some movies, there are these like pristine, lots of stainless steel, and acrylic, and everything is put away in their drawers, and in other movies there’s junk all over the place. Unfortunately, the latter is more like what our labs were.

In fact, I was just moving in– I had only been there six months. And so my lab was really filled with junk, except for this beautiful corner that had James’ stuff in it. And so actually, they took two boxes of junk from my lab for me. And instead of getting recycled, it went to the Ghostbusters set. So I thought that was pretty cool. My junk made it on camera.

IRA FLATOW: Of course, because it’s a biology lab, you know, if it were a biology lab, it would have to be pristine. But if it’s like one of those superheroes labs– what’s his name. I can’t think of his name. Now I’m going to have a senior moment about– he had three movies where he was an inventor. And he he could fly around in his lab.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Iron Man?

IRA FLATOW: Iron Man. Now Iron Man had a pretty junky lab, right? All kinds of stuff around there?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Exactly. But I think that’s a little closer to what they decided they needed here. But even more so if you’re working on a budget like they were at the University that was being portrayed in Ghostbusters. So they needed even more junk to build their experiments from.

IRA FLATOW: James, were you a big fan of the original Ghostbusters?

JAMES MAXWELL: Oh absolutely. Well, so I was two when Ghostbusters 1 came out, so I was a little young. But when Ghostbusters 2 came out, I was seven. I can remember my parents talking to other parents in the neighborhood and wondering, with seven-year-olds, can we show them this PG-13 movie. But once we saw the movie, my friends and I were totally in love. My friends had all the little action figures and play-sets and stuff. And so we played Ghostbusters on the playground for sure.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with Dr. James Maxwell and Dr. Lindley Winslow, who were advisers to the new Ghostbusters movie. Were you a fan, Lindley, of the original?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: I was. I don’t remember how many times I’ve watched this. My sister had a stuffed Slimer that I was very jealous of.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s your take on– well, let’s talk about the gender swap on this. What’s your take? Some people think it’s kind of controversial in some corners of the internet that the new cast is all women.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: So as a woman in physics, I was just in love as soon as they announced the reboot. And so when I got the e-mail, I was like, of course, I will take some time and show you around MIT. And I just don’t think you can stress enough the importance of role models to show young girls what is possible, and then give them permission for them to try things. You can solder, you can play with an oscilloscope, and look up on the screen at these people doing that. I thought it was great, especially that they portrayed experimental physicists, as an experimental physicist.

IRA FLATOW: Science is hot all over film now. In television, from the Big Bang Theory to other movies, to scientists being portrayed. This is a good time to be a scientist in film, is it not?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: I think so. And I’m very glad to see a diverse representation of scientists in film, and of all the different amazing things that you can study in nature.

IRA FLATOW: All right, James, I know– without letting secrets out– I know that you’ve seen the film at this point. Did it look like a movie that had consulted real scientists?

JAMES MAXWELL: Absolutely. I mean, even before Lindley and I came in to consult, we got to step into these sets there were just so amazingly realistic, and like she said, it’s gritty and it’s real, because scientists are not necessarily clean people all the time. But yeah, it felt like totally legitimate. A little science had leaked into this paranormal comedy somehow.

IRA FLATOW: Did you both see the set when it was finished before they were filming it or before?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Yes, I think that was my favorite part of this, was going and seeing the lab that they had built. And you know, wanting to go play with all the toys that they had put on the set.

IRA FLATOW: That’s my next question. Did it feel like you were home? You felt comfortable. This is not a movie set, this is my lab.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Yes, in fact, I think James and I got a little too comfortable. We were waiting around for the actresses to come, so we could meet them. And we’re just sitting there talking about physics, and they’re like, they’re going to start rehearsing now. You need to move. We’re like, oh right. This isn’t our lab.

IRA FLATOW: When I was on the set of the Big Bang Theory and they recreated the Science Friday set exactly like our studio, exactly how I felt. Wait a minute. I’m like, this is my spot. You’re not going to kick me out of this.

Where do you go from here? Have you been bitten by the movie bug?

LINDLEY WINSLOW: I think we were both hoping for Ghostbusters 4. Would that be? Did I get the number right?

IRA FLATOW: Sure.

JAMES MAXWELL: Yeah, four through seven. I’m rooting for it.

LINDLEY WINSLOW: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Thank you and we hope you get there. Well, we’re going to look forward to the movie. Dr. Lindley Winslow, an assistant professor of physics at MIT. James Maxwell, staff scientist, Department of Energy, Jefferson Lab. Thank you all for joining us today.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.