The Minds Behind The Myers-Briggs Personality Test

16:29 minutes

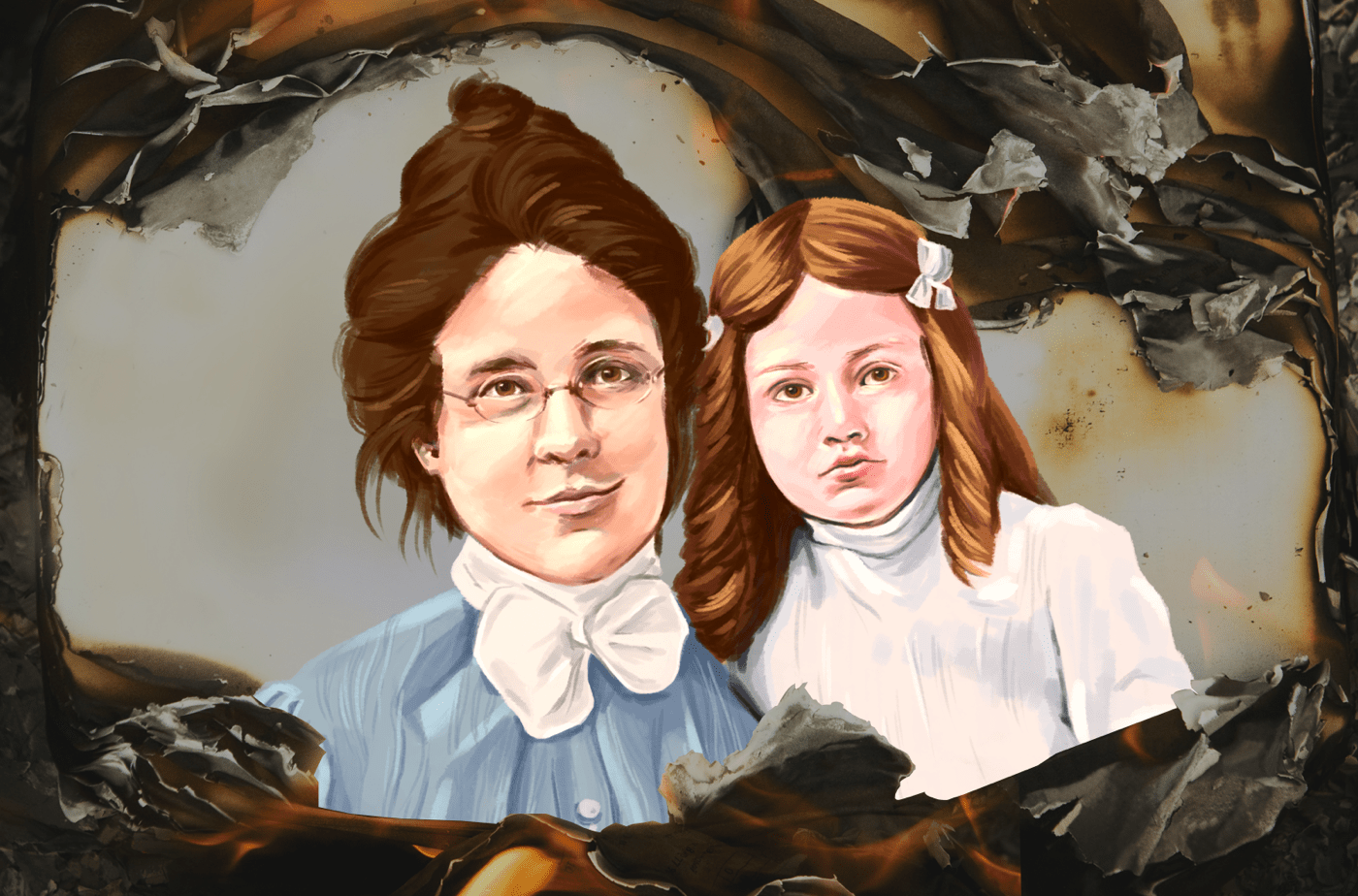

If you’re one of the 2 million people who take the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator every year, perhaps you thought Myers and Briggs are the two psychologists who designed the test. In reality, they were a mother-daughter team who were outsiders to the research world: Katharine Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers.

They may have been outsiders, but Katharine and Isabel did their homework, and approached the test the way a trained psychologist likely would have. And the product they created—the Myers Briggs Type Indicator—would eventually become the world’s most popular personality test. But how did it all begin?

Science Diction is releasing a special three-part series on the rise of the Myers-Briggs. In the first episode: A look at the unlikely origins of the test, going all the way back to the late 1800s when Katharine Briggs turned her living room into a “cosmic laboratory of baby training” and set out to raise the perfect child.

Science Diction host Johanna Mayer and reporter Chris Egusa join John Dankosky to tell that story.

Johanna Mayer is a podcast producer and hosted Science Diction from Science Friday. When she’s not working, she’s probably baking a fruit pie. Cherry’s her specialty, but she whips up a mean rhubarb streusel as well.

Christopher Egusa is a reporter and an Audio Engineering Fellow at KALW Public Radio.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankowsky. You ever take the Myers Briggs Type Indicator? You know, the famous personality test? You answer test questions and then get sorted into one of 16 personality types. Now I just took the test and I got the four letter result ENFP, which supposedly means that I’m an outgoing, open hearted, free spirit. Now you might assume that Myers and Briggs were psychologists but they were actually a mother daughter team who were complete outsiders to the world of psychology.

Our podcast, Science Diction, is releasing a three part series on the invention of the Myers Briggs personality test. Here to tell us more is Johanna Mayer, host of Science Diction, and Chris Agusa, a reporter who co-produced this episode.

Hello there, Johanna and Chris.

JOHANNA MAYER: Hi John.

CHRIS AGUSA: Hey.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: So before we go any further, I need to ask, what are your Myers Briggs types?

JOHANNA MAYER: Well I tend to get a different type every single time that I take the test, but I think most recently I got INFJ, which supposedly means I’m a little private, a little idealistic.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: Nice, very good. How about you, Chris?

CHRIS AGUSA: Yeah, so I’m an INFP, which apparently means I’m a little bit more spontaneous than Johanna and more open to new experiences.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: It takes all types I suppose. So the Myers Briggs is the most popular personality test in the world. But maybe you could remind me of exactly how it works?

CHRIS AGUSA: Yeah, sure. So you start by answering dozens of questions, questions like, when you go somewhere for the day would you rather A, plan on what you will do and when, or B, just go? And when you’re finished you get sorted into one of 16 personality types. And those types are made up of four different dimensions, introvert versus extrovert, sensing versus intuitive, thinking versus feeling, and judging versus perceiving.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: All right so I get how this is really fun and it’s irresistible to talk about, but you’ve already said that it wasn’t actually developed by psychologists. So I mean, who exactly were Myers and Briggs anyway?

JOHANNA MAYER: Yeah, so it was Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers. And they were two wildly ambitious and totally committed people but that is right, they were not trained psychologists. They were really outsiders to the research world. But I do want to say they did do their homework and they approached this a lot like a psychology researcher really might have. And Isabel, the daughter, eventually teamed up with a publishing firm that just marketed the heck out of this test and the personality tests that they developed, it is everywhere. I mean the Myers Briggs is used at Fortune 500 companies. People put it in their dating profiles, it’s just in all sorts of places.

CHRIS AGUSA: And people have opinions about it. Like we talked with a psychologist who could just not believe how much faith people have in this test. This is Dan McAdams, psychologist at Northwestern.

DAN MCADAMS: I know a number of people who swear by the Myers Briggs. These are smart people. I almost got into a fistfight with a guy one night when he just insisted that the Myers Briggs is all truth and goodness. And I said, well, there’s no scientific validity.

JOHANNA MAYER: And then on the other hand, we talked to people who say the Myers Briggs completely transformed their lives for the better, like Peter Geyer, who is a Myers Briggs practitioner. That was the first time anybody had ever told me it was good to be me. I was 36 by the way. So it’s a long time to wait before somebody tells you it’s good to be you.

CHRIS AGUSA: So over the next three weeks in this special series on Science Diction we’re exploring the stories of Myers and Briggs, who for better or worse have hugely impacted our modern ideas about personality.

Chapter one of our series starts in the late 1800s with the woman who laid the foundation for all of this.

JOHANNA MAYER: Katharine Cook went to college when she was just 14, graduated first in her class, and married the guy that graduated second, a certain Lyman Briggs. Lyman went on to a PhD program in physics but this is the late 1800s and Katharine was stuck.

MERVE EMRE: There is never any expectation that she will do anything other than be his wife and become the mother of his children.

JOHANNA MAYER: Merve Emre again, whose book The Personality Brokers, is all about the Myers Briggs Type Indicator.

MERVE EMRE: And she has three children, two of whom die in very early infancy and Isabelle is the only one who survives. And she has what she describes at that moment as a crisis of faith. And she thinks if I only have this one child, and if my entire life has to be determined by what I do with her as a mother, then I need to do something extraordinary. And I need to do something that is helpful to other people.

JOHANNA MAYER: So Katharine made a decision. She was going to professionalize motherhood. She would tackle it with the same ambition that her husband applied in his physics lab and by God, she was going to raise the most well-behaved, curious, exceptional, child imaginable. All she needed was a laboratory and a test subject. So Katharine took over a section of her house and established what she called the cosmic laboratory of baby training a.k.a., the living room. And our test subject, the baby to be trained, was Isabelle.

CHRIS AGUSA: It’s a whimsical name, the cosmic laboratory of baby training. But it was serious business. Isabel was still just a toddler but Katharine ran daily obedience drills with her and diligently recorded the results in her research diary. There were no no drills–

JOHANNA MAYER: Where she puts Isabel’s hand close to something that she’s not supposed to touch like a candle and she says no no every time her daughter tries to touch it

CHRIS AGUSA: And just stay drills–

JOHANNA MAYER: Which is Isabella supposed to walk just close enough to something to be able to observe it but not any closer than that. So when Isabel does well on these drills she’s rewarded with stories.

CHRIS AGUSA: Yeah, Isabel had a pretty intense childhood, and whether or not it was her mother’s training, Isabel did turn out to be an exceptional child. She was one of those kids who was good at everything from piano to metalworking. She was reading novels at age five. A neighbor once warned Katharine that Isabel would die of brain fever if she didn’t cool it. Soon other mothers noticed how well-behaved Isabella was so Katharine opened up the cosmic laboratory of baby training to other neighborhood kids, from eight-year-old Jane to six-month-old Louis. And Katharine didn’t just train these kids she studied them. She wanted to know exactly who they were. So each month Katharine sent parents a questionnaire about their children, their behavior, and their personality. Her goal wasn’t to know each child’s soul like in a modern, we’re all beautiful flowers with unique needs and dreams, kind of way. Katharine believed that each person had a duty to fulfill, a service to society, whether it was entertaining people on the stage, building homes, healing the sick, everyone had a role to play. And if we knew what type of person they were we’d raise them right, slot them into the right box

JOHANNA MAYER: Katharine started writing a popular column on parenting, kind of like a precursor to celebrity mommy bloggers except her methods would not go over so well today. She once told another mother that spanking is medicine. And her articles had some very questionable titles, like she knew a woman whose daughter, Mary, had failed the first grade. And eventually Mary made it into one of Katharine’s articles titled Ordinary Theodore and Stupid Mary. Things were going well for Katharine. She’d professionalized motherhood, cranked out a star child, and dispensed parenting advice to mothers across the nation. And then Isabel left, off to college, and Katharine, bereft, like her life’s work had just up and vanished, Which it kind of had. She fell into a deep depression.

CHRIS AGUSA: And then she had a dream. She told Isabelle about it later. It was about Carl Jung, the Swiss analytical psychologist. He’d recently published what would become one of his most influential books, Psychological Types. And in Katharine’s dream, Jung showed up at her house. He cut out paper dolls with her children and rode away on a giant horse. It was a weird dream but Katharine took it as a calling.

When she woke up, she took all of her own notes and burned them in the living room. She didn’t need them anymore. From then on she would turn her full attention to life as Jung’s disciple. Katharine was totally taken with Jung’s theory of personality, and his words, introvert and extrovert, which he defined as whether you turned your psychic energy inward or outward. And sensation versus intuition, when making decisions do you pay more attention to what’s happening in the physical world around you or do you trust your gut? And this just clicked for Katharine.

She took Young’s language and in 1926 cobbled together a little grid with different possible personality combinations. It was the first real blueprint of what would become the Myers Briggs.

JOHANNA MAYER: You know how people can get fixated on one idea and it just becomes their lens for everything? Like it could be evolution, or dialectical materialism, or the illuminati, varying degrees of validity of course, but this one idea just explains everything for them. For me it’s always capitalism, capitalism, capitalism. Why did my sink clog? Capitalism. Why is my cat ignoring me? Capitalism. Well Katharine’s universal theory of everything was that personality came in types. And she used type to explain almost everyone’s behavior.

This urge to put people in personality boxes, it isn’t unique to Katharine. The ancient Greeks had a theory with just four boxes. A person could be phlegmatic, choleric, melancholic, or a sanguine type, depending on the balance of fluids in your body. And we’ve come up with plenty of other personality sorting schemes, zodiac signs, Harry Potter houses, Sex and the City characters, every single BuzzFeed quiz. But back in the 20s, Katharine had caught on to a few things that made her system especially appealing. First, it was simple enough that anyone could understand it but the Junian language gave it a sheen of authority and rigor. But more than that, Katharine’s types let people feel unique and seen. The ancient Greeks might tell you you’re an angry choleric or a depressive melancholic. A psychologist might say you’re neurotic or antisocial but for the most part Katharine’s system was reassuringly positive. If you’re an extroverted, intuitive type it means you’re an explorer, an inventor, keen minded. If you’re an introverted feeling type you might be a little quiet and reserved. But that’s because you’re not hung up on impressing other people. Instead of diagnosing our differences, Katharine’s system seemed to affirm them. In her world, everyone had a role to play and her type system was the gateway to discovering it.

I’m Johanna Mayer and you’re listening to an episode of our podcast, Science Diction . This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

CHRIS AGUSA: As utopian as that sounds this line of thinking also had a dark side.

MERVE EMRE: When I was reading her parenting advice columns one thing that struck me was how closely they mirrored some of the language of eugenic thought. She basically believed that one thing that personality assessment could be used for was to identify intellectually strong members of society versus intellectually weaker members of society.

CHRIS AGUSA: For Katharine, it was all about optimizing society, ushering people into their ideal roles, and thereby advancing society as a whole. She called for the unique treatment of different types of people.

MERVE EMRE: Essentially life plans that would allow the strong to rise to the top, and that would allow the weak either to be sort of brought up to levels of mediocrity. Or in some cases, simply called off. And she’s not specific about what that means. But there certainly is this sense in her writing that if you identify children who are weaker than others, It doesn’t make as much sense to give resources to them as it does to give resources to stronger members of society.

CHRIS AGUSA: It is worth noting that this was pre World War two and eugenic thought was somewhat mainstream at the time. But years later Isabel would inherit some of these ideas. And some still see echoes of them in the indicator today. In 1935 Katharine finally closed her cosmic laboratory of baby training for good. And the next year, at last, she got a chance to meet the man she called her personal God, Carl Jung.

She’d actually been writing him letters for years and sometimes he’d write back. And now he’d be in the United States for a conference and agreed to squeeze Katharine in for a meeting. She dragged Isabel to her meeting, maybe out of nerves, maybe to share this monumental moment with her daughter, who is now nearly 40 years old. But Isabel was unimpressed. She later claimed she didn’t even listen to the conversation between her mother and Jung. But for Katharine the day was transformative. It was just a quick appointment in Young’s hotel room.

Katharine told him how she’d burned her own writing after reading his. And he was kind to her. Their relationship as occasional pen pals had become strained in recent years. He’d been terse with her over what he saw as meddling in other people’s affairs. And once expressed irritation that she wasn’t using enough postage on her letters, leaving him to pay the difference. But at this meeting Jung encouraged her. He told her that it was a mistake to burn her notes and that she could have made a real contribution. And then before they parted Katharine offered him what she could to support his great work, money. She handed him a check for $25, what would be about $500 today. She said she wished it could be more.

JOHN DANKOWSKY: That was the first episode in a new three part series from Science Diction on the Myers Briggs Type Indicator. So Johanna, what’s coming up in chapters two and three?

JOHANNA MAYER: So it turns out that Kathryn had way more to offer the world than $25. So next week we’re going to pick up the story with Isabel who picked up her mother’s work and really started to shape the Myers Briggs into not just a personality test, but THE personality test.

CHRIS AGUSA: And then in chapter three we’re going to get into the big question. Does it actually work? Or is it all just junk?

JOHN DANKOWSKY: I’m looking forward to this can hear all of these episodes on Science Diction wherever you get your podcasts Johanna Mayer and Chris Agusa, thanks so much.

JOHANNA MAYER: Thank you

CHRIS AGUSA: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.