The Little Plankton Recorder That Could

9:56 minutes

For half a century, merchant ships have hitched humble metal boxes to their sterns, and towed these robotic passengers across some 6.5 million nautical miles of the world’s oceans. The metal boxes are the “Continuous Plankton Recorder” or CPR, a project conceived, in a more innocent time, to catalogue the diversity of plankton populating the seas.

Then, in 1957, a messenger from a more polluted future became tangled in the device. “Recorder fouled by trawl twine,” read the recorder’s log. Modern-day researchers haven’t been able to confirm that the twine was plastic, but they believe it might have been, due to the growing use of plastic fishing lines in the 1950s.

In 1965, a less ambiguous specimen appeared in the logs: a plastic bag.

In the decades since, the recorders have been fouled by more and more plastic pollution, so much so that plastic debris now far outnumbers materials of natural origin. One might even mistake the “P” in CPR to refer to plastic.

But, true to the device’s original mission, the recorders have also made biological discoveries, such as a pirate plankton invading the North Atlantic via the melted Arctic, a species that hasn’t been seen in the North Atlantic for 800,000 years.

Clare Ostle, a marine biogeochemist and lead author on a study about the CPR’s plastic finds in the journal Nature Communications, joins Ira to talk about the treasures and trash the CPR has collected over the years.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Clare Ostle is a marine biogeochemist with The Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, United Kingdom.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I am Ira Flatow. In 1965, marine scientists fished a very odd specimen out of the Atlantic waters. It was a plastic bag. That bag, as we know now, was only the beginning of an onslaught of plastic trash that would soon foul the world’s waters, choking and entangling sea creatures, massing into giant floating garbage patches.

Scientists have now compiled a record, a who-done-it of plastic pollution that describes the when, the where, and the how of ocean garbage. And they did it all via a collection of humble metal boxes towed through the world’s oceans for half a century. Towed behind ferries and container ships, an ambitious but unsung project called the Continuous Plankton Recorder.

Joining us now to talk about the CPR, as it’s called, is Dr. Clare Ostle, a marine biogeochemist at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth in the UK and author of a new study on plastic trash in the journal Nature Communications. Welcome, Dr. Ostle.

CLARE OSTLE: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: This is really an old experiment, right? It’s been running in some form back to 1931. What was the origin of this idea?

CLARE OSTLE: Exactly, yeah. Well, it was actually started between 1925 and 1927 by a man called Sir Alister Hardy, and he was a zoologist on one of the research vessels that was in the southern Atlantic. And they were tasked with tracking the movements of whale populations for a fishery, and so he had the brilliant idea that, if you want to know where the whales are, you need to know where the plankton are. So he designed this contraption to go off the back of the ship and continuously collect plankton in a silk roller.

IRA FLATOW: Describe what the thing looks like and how it works. You say it has a silk roller. And as it’s towed through the water, what happens?

CLARE OSTLE: Sure. So it’s like a big metal torpedo, about one meter long. And what happens is, now, we use container ships, ferries, any kind of commercial vessels, and they use a metal wire to throw it off the back and they attach it to the back of the boat, and what happens is the water enters through the front. And you’ve got kind of like a cassette rolling on the inside with two pieces of silk.

And as the water passes through the silk, anything that’s in the water column, so the plankton, even tiny bits of microplastic, all sorts gets trapped on that silk and it kind of forms a plankton sandwich, and that’s stored in the plankton recorder. And then, at the end of the tow, it’s pulled back onto the ship and the samples are sent back to our lab here in Plymouth and they’re analyzed.

IRA FLATOW: And so how many of these boxes exist now?

CLARE OSTLE: Well, we’ve got about 53 Continuous Plankton Recorders in our current UK fleet, but we have plankton recorders all over the world now. We’ve got them towing in the North Pacific, around Australia in the southern ocean, so it’s growing continuously.

IRA FLATOW: And you actually rode on a banana ship towing one of these things?

CLARE OSTLE: Yeah, that was during my PhD. I was on a big container ship that’s called a banana reefer, so they pick up bananas from the Caribbean and it brings it back to the UK, and these huge containers are basically like big refrigerators. And yes, that had a Continuous Plankton Recorder off the back.

IRA FLATOW: So how does a banana ship get one of these? Do they ask for it? Are they getting paid to do it? Is it all voluntary?

CLARE OSTLE: It’s all voluntary. So we’re very, very fortunate that we have a great network of shipping companies that we work with. And basically, we ask them to tow these things. And they very, very generously do it for free.

IRA FLATOW: And so how many miles do you think you have covered in the 70, 80 years this has been going on?

CLARE OSTLE: We’ve covered over 6.5 million nautical miles now, which is equivalent to about 12 times to the moon and back.

IRA FLATOW: And do you have to haul it out of the water every couple of hours to check if it’s gotten all tangled up, stuff in there?

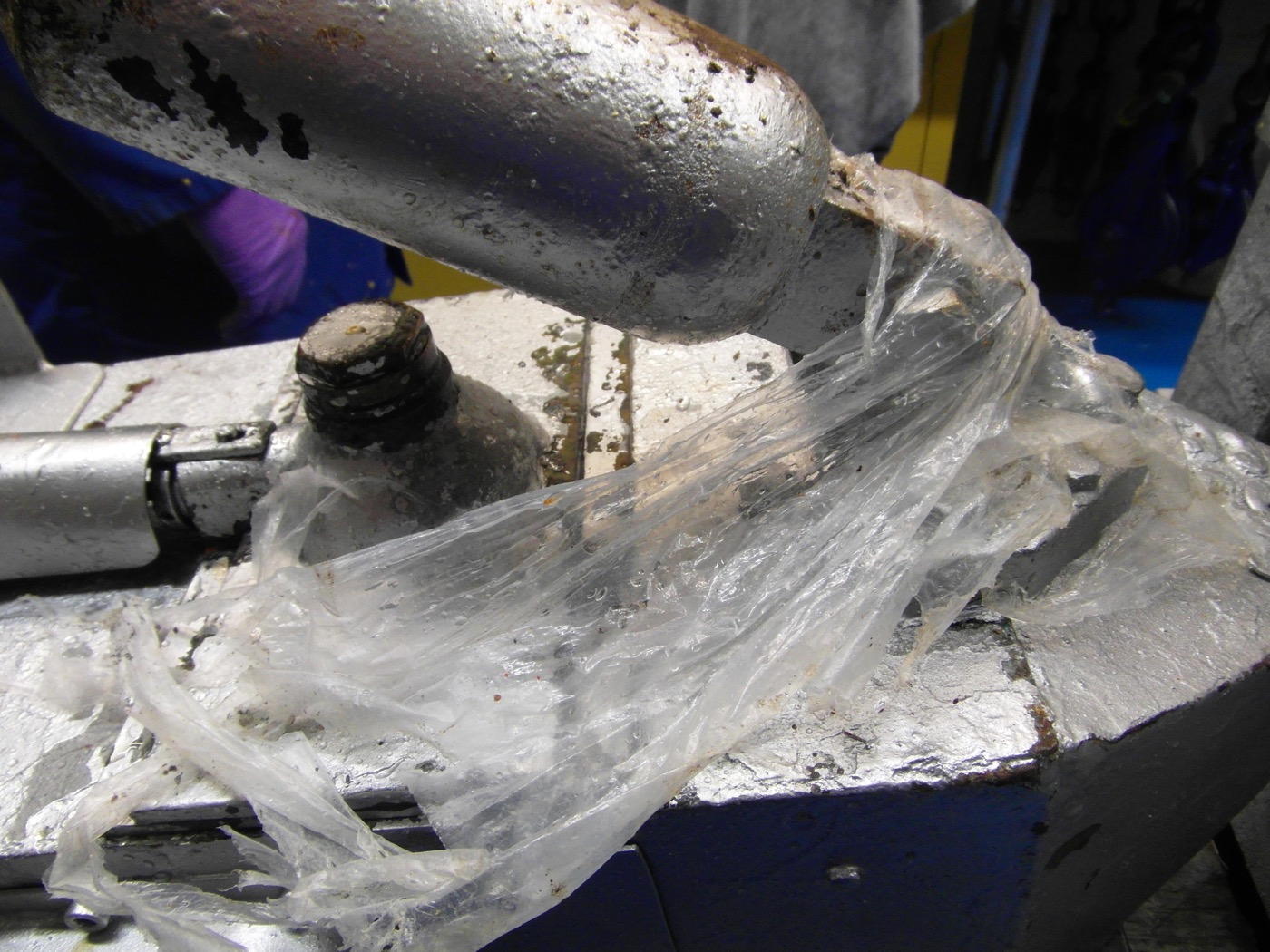

CLARE OSTLE: Well, what happens is the cassette has changed over. So after about 500 miles, the crew will pull in the Continuous Plankton Recorder, and that’s where they’ll note down any kind of entanglements or issues with the recorder, and that’s where we built this plastic database of the larger plastic items. But yeah, that’s when they take out the cassette and they put a new one in to start a new tow.

IRA FLATOW: Your study out this week tracks the appearance of plastic in the ocean. I was reading the comment about 1965, that they were surprised to find a plastic bag in the ocean, how foreign that sounds now.

CLARE OSTLE: Yeah. No, it was quite crazy. We were getting more and more plastic entanglements on the Continuous Plankton Recorder, and I was chatting to the guys in the workshop that fix these things up every day. And so we started to say, well, you know what? We’ve got these amazing logbooks where the crew record exactly when they put the plankton recorder in the water and what time it’s coming out, and they also note what the weather’s doing, all sorts of different things. So I said, well, let’s look through that logbook. And yeah, there the plastic bag was in 1965.

IRA FLATOW: Can you also detect the tiny microplastics that are there?

CLARE OSTLE: Yeah. So actually, one of the first studies that was done to coin the term microplastics was written in 2004, and that was by Professor Richard Thompson who’s based at Plymouth University. And he used the plankton recorder, the silk samples, to go back through time because we store all of our samples in a massive biological library. So he went back through time and went into each decade on a particular route, and he picked out the samples and then counted the microplastics to demonstrate that these were a thing and that there [? wasn’t ?] an increase up until about the ’80s, in this particular study.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I understand that the Continuous Plankton Recorder also discovered a sort of marauding plankton species back on the scene in the Atlantic many years after it disappeared. You found it.

CLARE OSTLE: Yeah, that was a Neodenticula seminae, so it’s a type of diatom, and generally, it’s found in the Pacific Ocean. And kind of around the Millennium, we started to see it in our Continuous Plankton Recorder samples. And that was in the Atlantic, so we hadn’t seen that species in the Atlantic according to sediment cores for over 800,000 years. So it’s likely that that was due to changes in temperature and the currents that are occurring around the Labrador Sea, so that it was able to pass through the Northwest Passage.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So you’ve got something like 50 or so of these recorders dating back to almost 100 years of recording. What do you do with all the stuff it picks up? Do you store it someplace?

CLARE OSTLE: Exactly. We keep all of those samples, so we have a huge kind of warehouse. It’s all temperature controlled and very well ventilated because we use a preservative in our samples. And there, we’ve got just stacks and stacks of very organized samples.

IRA FLATOW: So is there value in all those samples? I mean, it basically is a museum with historical value.

CLARE OSTLE: It’s hugely valuable. We’re finding more and more now as the data set’s growing, and we’ve got up to 80 years of data now. People are coming in with new ideas and new things they want to look at, new technologies. For example, eDNA, so genetic analysis has become a really big thing right now, and there’s a lot of new techniques. And so we’re looking at applying that to some of these historic samples as well to see how ecosystem and other things has changed.

IRA FLATOW: Can you also see how plastic might biodegrade being out in the ocean that long?

CLARE OSTLE: Potentially. I think there is work to do that. We’re kind of starting to look at the elements, the composition of the plastics that we’re getting. And using certain, basically, identities of the plastics, you can work out and date where that plastic might have originated from.

IRA FLATOW: Now, say I want to get my own recorder. How do I go about applying to drag one behind my boat?

CLARE OSTLE: Well, we’d be very happy to get one built for you, I’m sure.

IRA FLATOW: What size boat do you need? I mean, can a 20-foot sailboat be good enough, or what do you need to [INAUDIBLE]?

CLARE OSTLE: No. Generally, we go for the big boats. We do have a small kind of version of the plankton recorder called an ocean indicator, and we have used that occasionally, actually, off sailboats. And there was a trip that went out around the Pacific through the Garbage Patch actually using one of these smaller recorders, and that was a sailboat. But no, the plankton recorders are really heavy, and so you’d want a big boat with a big engine on there.

IRA FLATOW: So your design hasn’t really changed in 100 years of making these?

CLARE OSTLE: No, that’s why it’s so unique. So the design of the Continuous Plankton Recorder, even everything down to the weave of the silk mesh has remained consistent throughout, and that’s why we’ve got such a consistent time series of data.

IRA FLATOW: I’m surprised there are no fancy lasers in it or measuring devices. It’s just– what you see is what you get from back then.

CLARE OSTLE: Exactly. We are starting though to add– I mean, so I don’t know if you’ve seen some of these seal tags. You get these amazing sensors that they’re sticking onto seals to get all sorts of information about salinity and temperature. And we are starting to add some of those small sensors, so we’re kind of combining the old with the new. And as long as it doesn’t change the flight of the plankton recorder and the way the mesh is working, then we’ve got all sorts of things to play with there.

IRA FLATOW: Well, congratulations to you, and we wish you great success for the next 100 years.

CLARE OSTLE: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Clare Ostle is a marine biogeochemist at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth. That’s in the UK, Plymouth, and we have a picture. If you’ve whetted your appetite about this, we have a picture of the Continuous Plankton Recorder up on our website at ScienceFriday.com/CPR.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.