The Explorations Of An Early Climate Change Detective

21:13 minutes

In 1799, the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt embarked on the most ambitious scientific voyage of his life. On the Spanish ship Pizarro, he set sail for South America with 42 carefully chosen scientific instruments. There, he would climb volcanoes, collect countless plant and animal specimens, and eventually come to the conclusion that the natural world was a unified entity—biology, geology and meteorology all conjoining to determine what life took hold where. In the process, he also described human-induced climate change—and was perhaps the first person to do so.

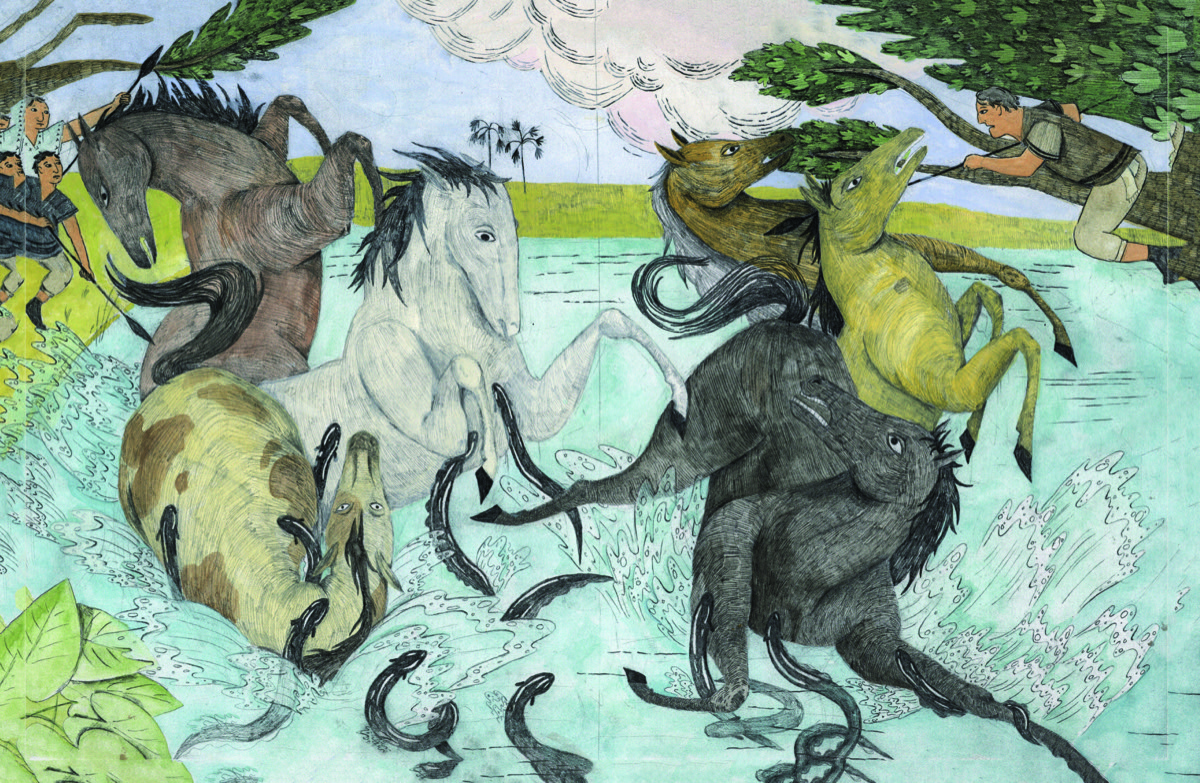

Author Andrea Wulf and illustrator Lillian Melcher retell the voyages of Alexander von Humboldt in a new, illustrated book that draws upon Humboldt’s own journal pages. Wulf and Melcher will discuss why they think his legacy should be better known in the modern fight against a changing climate. Read an excerpt of the new book The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Andrea Wulf is the author of The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt, The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World, and The Founding Gardeners. She’s based in London, England.

Lillian Melcher is an illustrator living and working in Boston, MA. Her first book is The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt (Pantheon, 2019) written by Andrea Wulf.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, what can artificial intelligence learn from a real brain? Scientists hooked up the two together, and they found some really interesting stuff that we’ll talk about a bit later.

But first, here’s a story that may sound familiar. An inquisitive European naturalist boards a ship, sets sail for South America. Along the way, he collects countless specimens, scales mountains, describes everything he encounters. Making countless observations, he develops a new theory about the interrelationship of the natural world. You’re thinking Charles Darwin, right? Sounds like him. But not this time. It’s Alexander von Humboldt, Prussian polymath, who voyaged on the Pizarro decades before Darwin on the Beagle.

And my next guests are here to tell you, in a beautifully illustrated new book, that we should be thanking Humboldt both for inspiring Darwin, as well as being the first person that we know of to observe human-made climate change.

Here to tell the story are my guests, Andrea Wulf, the author of The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt. She lives in London. Welcome.

ANDREA WULF: Hi there.

IRA FLATOW: And Lillian Melcher, who illustrated the book, she joins us from Boston. Welcome to Science Friday.

LILLIAN MELCHER: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Andrea, this is not your first visit to our airwaves to talk about von Humboldt. Your last book, The Invention of Nature, was our first look at this rather amazing adventurer. Why did you need another book?

ANDREA WULF: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that’s a question I get asked a lot. So basically, when I finished The Invention of Nature, when I finished the manuscript of The Invention of Nature, the legendary Humboldt diaries, which had been in private ownership until then, were bought by an archive in Berlin. That wasn’t a problem really in terms of content. So I have transcriptions of these diaries for The Invention of Nature.

But when I saw the 4,000 pages which were filled with Humboldt’s rather indecipherable handwriting but also with hundreds of sketches, I knew that I wanted to do another book, a book that showed his artistic side. Because these pages had just sketches of monkeys and flowers and birds and fish and profiles of mountains and maps of rivers. So it was really a way to bring Humboldt to life in a different way, I suppose.

IRA FLATOW: So his diaries, these were the first time anybody got to see his drawings is what you’re saying.

ANDREA WULF: Yes, so we had descriptions. So we had– the words we had. But they had been in private ownership. So the archive in Berlin made them available online. So everybody can have a look at them, all 4,000 pages. And they’re absolutely beautiful and incredible.

IRA FLATOW: They are in the book. And if our listeners would like to talk about it, our number, 844-724-8255, You can also tweet us at @SciFri.

Lillian, when you look at Humboldt’s journals, his drawings, what do they say about how his mind worked, from one artist to another?

LILLIAN MELCHER: Well, I think it really shows how much he wanted to make science accessible. He wasn’t– it was as if he was writing the manuscripts not only for his own recollection, but also thinking of people in the future reading them. I think he was thinking that we need to know what this leaf looked like and how this tent was constructed. And in illustrating this book, his meticulousness came in handy quite a lot.

IRA FLATOW: And you bring to life an amazing array of adventures in this book. Humboldt climbed volcanoes. He witnesses meteor showers and at one point capsizes his boat in the Orinoco River? What– what were some of the most satisfying stories? What was the most satisfying for you to illustrate? What did you find?

LILLIAN MELCHER: I think my most satisfying moment– and it was really a moment where I felt like I was conversating with Humboldt himself. There’s this one moment where his servant falls through a snowbank, a snow bridge, into a massive crevasse on top of a volcano. And he describes this moment in so much detail. And he even draws a little diagram with each point labeled with a letter, and then that letter further describing what happens at each point. So I was really able to take this moment in history and bring it to life from all these different perspectives that it wasn’t seen from before.

I think that was my favorite moment to draw because it was obvious that moment was important to Humboldt. And so bringing it to life was a real pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, so it sort of illustrated a bit about his personality, did it not?

LILLIAN MELCHER: It really did. You learn so much about Humboldt as a person from what he puts in his manuscripts and what he leaves out and what he chooses to really expand on. So creating a character from this writing was not only sort of easy because he wrote with a lot of emotion, but also, I think it’s really important to see the whole story from a different perspective.

IRA FLATOW: Andrea, what are some of your favorite stories from this voyage?

ANDREA WULF: Well, my favorite stories were slightly different before I started this book. Because the way Lillian brought them alive maybe made some of the stories some more accessible for me. So one of my favorite pages in this book now is when Humboldt and Bonpland, his traveling companion, when they almost drown in the Orinoco.

And the way Lillian created this is she created the Orinoco made out of the pages from the diary. And then Humboldt rescues his diary when he’s in the water through a watermark that actually is on the page of the diary, which I found when I was reading through the diary. So there are all these different levels. So I absolutely enjoyed that.

And then I really like the moments when he’s climbing the Andes, when he sees the world in a completely different way. Because when he climbs the Andes, which he climbs Chimborazo, which he believes to be the highest mountain in the world, and he has almost like an epiphany up on this mountain. And it’s a moment when his vision of nature clarifies and when everything that he had seen before becomes clear and falls into place. And he understands nature for the first time, truly as a global force.

And I think, for me, those are the moments, which are very important. And maybe also because I went up the Andes. I went up to Chimborazo. So I feel– when Lillian says she feels very near to him when she sees his drawings, I feel often very near to him when I’m in the same places as he went to.

IRA FLATOW: You know, the idea that nature is all-encompassing, that there are ecosystems, there are ecologists who study it, they’re all ideas familiar to us today, but not back then.

ANDREA WULF: No, Humboldt is really the first who comes up with this idea. So at that time– so he goes to– he travels to South America in 1799. At that time, scientists are very much looking through a very narrow lens of classification of nature. So they are imposing an almost rigid system on nature.

There is Humboldt, who sees this journey from Quito up to Chimborazo like a botanical journey. So he sees how the plants, from the tropical species in the valley up to the last bit of snow lichen up the– the bit of snow lichen up near the snow line– he sees how they change with altitude. So he really understands vegetation zones, global vegetation zones, global climate zones. And he gives us a concept of nature that’s still very much shapes our thinking today. He describes nature as a web of life. And he describes Earth as a living organism, which is something completely new at that time.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting, because it was Charles Darwin, as I said at the beginning, whose name comes to us when we think about this. But Humboldt preceded Darwin. And did Darwin say that he was an influence on his career?

ANDREA WULF: Yes, very much so. So Darwin said that it was Humboldt’s writing, Humboldt’s books, that actually made him want to go on the Beagle. And amazingly, on the Beagle, he had his Humboldt books on a shelf next to his hammock. And these books still exist today. And when we look at them, we can see that Darwin underlined them. So they are heavily annotated.

So reading those books gives us an idea how Humboldt influenced Darwin. And it’s almost like listening to the two of them having a conversation. So ideas such as the transmutation of species, for example, is something that Darwin underlines in Humboldt’s books already.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Interesting. Let’s go to the phones to David in Reno. Hi, David. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAVID: Well, thank you. And my thanks to Andrea Wulf for bringing attention to this great scientist through her books. Our state of Nevada has the Humboldt River. It has a county named Humboldt. And it also was almost named Humboldt as a state. And recently, we had a proclamation in the Nevada legislature honoring Humboldt’s 250th birthday. So my question to the guests is, how do we get more recognition for Humboldt in the United States?

IRA FLATOW: Read the book, I guess, to begin.

ANDREA WULF: [LAUGHS] Yeah. That was exactly what I was about to say.

IRA FLATOW: I knew you were. That’s why– I knew there was a silence there waiting for me to say it.

[LAUGHTER]

LILLIAN MELCHER: That would be a nice start.

IRA FLATOW: But it’s true, you know. We– Americans, we have places named after people and certainly Humboldt. You know? We see it up on a sign, but we don’t know who he was.

ANDREA WULF: Well, they– I mean, I gave a talk at the Humboldt State University. And a lot of students that don’t know why Humboldt State University is called Humboldt State University. So they think it’s called Humboldt State University because of Humboldt County. So–

IRA FLATOW: Did he spend time in the States here?

ANDREA WULF: He came to– he went to Washington, so he met Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. But he never went West. He wanted to, but he never managed to. Because he’s so restless and curious that he just kind of gets distracted by other things. But a lot of his followers went then West and named a lot of things after him. So that’s the reason why there are many places and counties and bays and rivers named after Humboldt in the Western US.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And how did you decide, Lillian, what to illustrate? I mean, there’s so much that he did. Was it an over-arcing feeling?

LILLIAN MELCHER: Well, yeah, I mean, there were definitely points that we needed to hit, certain experiments that we definitely wanted to bring to life. But at the same time, I mean, a lot of it was dictated by Andrea’s writing, which, of course, came directly from his manuscripts. Some of these events in his manuscripts are just so over-the-top and just exciting in themselves that you can’t not illustrate them.

IRA FLATOW: It’s quite interesting. I want to– let me go to the break because there’s so much more to talk about. I don’t want to interrupt you. Let me just remind our listeners that we’re talking about this great new book that’s out there. And it is profusely illustrated. It’s just wonderful, The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt. Lillian Melcher is with us. She’s the Illustrator. Andrea Wulf is the author of The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt also and has written about him before.

And if you’d like to talk about this guy we don’t talk about a lot, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us at @SciFri, 844-SCI-TALK.

We’ll talk about some of the really interesting illustrations and how you decided to depict them, for example, an really interesting drawing about Humboldt in Havana. We’ll talk about it after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. In case you’re just joining us, we’re talking this hour about the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, his theory about the unity of nature, and what we can learn from him as we face climate change today with my guest Andrea Wulf. She is author of The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, and also the Illustrator, Lillian Melcher. Our number, 844-724-8255.

Let’s turn to some of your illustrations. Lillian, I’m looking at a page that depicts Cuba– Havana, Cuba. And it’s beautifully illustrated and I’m looking at it as you drew it. And it seems like you tried to recreate the feeling that he had when he was in the city there. The paper is full of dark splotches. It’s confusing.

LILLIAN MELCHER: [LAUGHS] Yes, well, this page in particular was an example of one my favorite things that comics can bring to the story. You’re depicting these instances with image and with text. So you’re able to sort of elicit an emotional response. So part of that for me with Humboldt was recreating as much of his tactile experience as possible.

And on this page in particular, he’s completely devastated because all of his manuscripts are covered in mold, and they’re being eaten by bugs. And so I really wanted a contrast to show between the manuscripts on this page and the manuscripts on previous pages. So these pages are covered with these moldy splotches and these bugs and these moldy leaves.

And for this page, I actually put printouts of these high resolution scans of Humboldt’s manuscripts into my mother’s shed. And I covered them with what I would call gross things from my fridge, including orange juice and milk. And I let the mold grow. And it was very successful. And I’m quite proud of my disgusting page.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] It’s so beautifully done. And also what I like about it, as you say, it is a sort of a comic book. There are little bubbles of people talk, like they do in comic books. How did you choose what they’re saying to one another on the page?

LILLIAN MELCHER: Well, what they’re saying was written by Andrea and pulled from stories that were in the manuscripts. So you know, we would go in, and we would decide how is this story going to be best represented. And she would give me a script. And that script would have body text and dialogue. And we would– often, I would just stick with what she decided. But sometimes we would decide, you know, this body text would be better said by someone. Or you know, we could have Bonpland talk in this moment. So you know, really, having these historical figures say what they mean, you know, it’s really great.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, you were very creative in your technique. You can see that. And I know you had some interesting problems to solve in making this book, like when you needed an overhead image of the Amazon rainforest.

LILLIAN MELCHER: Yes, well, a lot of the issues were solved by looking back to Humboldt’s life and times, you know, making design decisions based on that. But for the Orinoco pages, I really wanted there to be these aerial trees so it was like you were looking at the Amazon flow through the pages. And we could also use those to collage over the manuscript pages. But I couldn’t find a good picture of trees overhead.

But I actually had a friend in New York who I met on Tinder. And he was able to give me some aerial footage that he took in Guatemala of some trees. So not quite Amazon, but I took it because it was free. And he was a very good friend for doing that. [LAUGHS]

IRA FLATOW: That’s a great story. You always need– you gotta have friends, as the song–

LILLIAN MELCHER: You gotta have friends.

IRA FLATOW: So let’s go to our friends in San Francisco. Let’s go to Charlie. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

CHARLIE: Hi, I’m delighted to make acquaintance with the authors. And I was wondering if Humboldt found love in his life or if he was basically married to his work and his sense of mission and to nature?

IRA FLATOW: Andrea?

ANDREA WULF: Well, so he always said his first love was the science and nature. But most historians, including me, are pretty sure that he was gay. So he never married. There was never an important woman in his life. There were a lot of very intense friendships with male scientists.

So we don’t really know if he ever physically experienced this love. But what we do know is that he had these very intense relationships with men.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. You say that he’s the first person who described human-induced climate change. Give us the story on that. How did he figure it out?

ANDREA WULF: He basically traveled through South America. And he saw– as he traveled, he saw again and again how humans destroyed nature. And he became very aware of things like the destruction of the forest, the consequences of irrigation, of mining. And as he traveled, he kind of put these things together.

And there are some really extraordinary moments in his diary. For example, in 1801, he writes that there might be a future when we will travel to distant planets. And then he said, what we will do is we will bring our lethal mixture of vice, ignorance, and violence with us. And we will turn these planets– and this is what he says– as ravaged and as barren as we’ve already done with Earth. So pretty prophetic, I would say. He also warned of the gas masses from industrial centers. So he’s very much aware of what’s happening. He explains the fundamental function of the forest for– you know, that forests can store water and protect against soil erosion. So he has this global view of nature.

But he also does something, which I think is very important for today’s climate change debate, where he is a scientist who allows us to inject emotions and imagination into discovery. So he says again and again that we have to use our imagination to understand nature. He’s driven by this sense of wonder, which I think is an emotional dimension that very much, you know, we are missing in our climate change debates today, where we get– we are bombarded with dry statistics and numbers. But Humboldt is someone who has always said that we need to also feel nature in order to understand it.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you get that feeling. I imagine that it is one of the reasons why you write a comic like this is written in a comic style is that it does evoke a feeling than just black and white writing on the page, Lillian and Andrea.

ANDREA WULF: Yes, it was–

LILLIAN MELCHER: Yes.

ANDREA WULF: I think we both agree on that, that, for me, the reason was that I wanted to show that Humboldt is an artist and a scientist and kind of bring this emotional dimension to. It and then Lillian kind of took it and turned it into this, I think, lush and almost visceral experience with Humboldt.

IRA FLATOW: Lillian? I mean, even the cover is a lush experience, looking at it, beautifully drawn, multicolored flowers.

LILLIAN MELCHER: Yes, but I think the comics are having more and more of a place within the sciences. I think it’s a conversation that has to be had because, you know, we need to be taking action. And action starts with the people. And we’re a very visual culture. And so by combining the words of scientists with images that really evoke emotion, we can create something that can be more popular and accessible.

And I think that was always the goal of Humboldt. I think he was very successful at it. And I think we need more of that today.

IRA FLATOW: And you can see some of those gorgeous images and have those feelings being evoked in yourself. We have some images from the book, an excerpt from the book, on our website at ScienceFriday.com/adventure. And you could just get the book yourself, The Adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, Andrea Wulf, author, and beautifully illustrated by Lillian Melcher. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

ANDREA WULF: Thank you for having us.

LILLIAN MELCHER: Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.