The Business Of Predicting Climate Change

22:28 minutes

No one is sure what that future will look like under climate change and increased temperatures. Scientists have predicted severe storms, higher sea levels and more flooding, and they build all sorts of models to predict the likelihood of these type of events. But it’s not just scientists who are interested in these models.

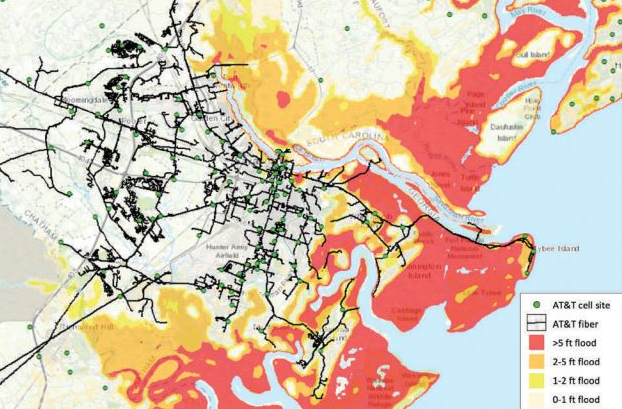

Telecomm giant AT&T teamed up with scientists at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois to build a climate map of the Southeastern part of the country, overlaid with a map of AT&T’s infrastructure. Climate scientist Rao Kothamarthi from Argonne Labs discusses the process of creating hyperlocal climate change models, and Shannon Carroll, director of environmental sustainability at At&T, talks about how the company can use that information for making decisions on how to protect their infrastructure.

Rao Kotamarthi is Chief Scientist in the Environmental Science Division at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois.

Shannon Carroll is Director of Environmental Sustainability for AT&T, based in Dallas, Texas.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When the talk turns to climate change, as it is increasingly doing, you can bet that people will discuss sea level rise or increased wildfires, more powerful hurricanes, and how cities and governments are getting ready or not. What you don’t hear a lot about is how companies are preparing to cope with the challenges ahead.

But now, the telecom giant AT&T is teaming up with scientists at Argonne National Labs to build a climate map– a detailed climate map– of the country. So why is AT&T interested in the climate? And will other companies follow suit?

Let me introduce my next guests. Shannon Carroll is the director of Environmental Sustainability at AT&T, and he is based in Dallas, Texas. Welcome to Science Friday.

SHANNON CARROLL: Hi, Ira. Great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: And Rao Kotamarthi is chief scientist of the Environmental Science Division at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois. Welcome to Science Friday.

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Ira, thanks.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Nice to have you. Shannon, AT&T isn’t known to deal in climate science. Why is the company so interested in developing this detailed climate map?

SHANNON CARROLL: Well, why is definitely the most important question but probably the easiest to answer, in this case. No surprise, extreme weather and climate change, it impacts everyone, and that includes AT&T. So from our perspective, our customers, our employees, the communities in which we serve, they depend on us to not only maintain a great network today but into the future. And that means being climate resilient.

IRA FLATOW: And so what do you mean? You’re worried about the winds, the waters, or all those things?

SHANNON CARROLL: Well, for this first go-around– we’re piloting this, essentially, right– so we have four states that we’re doing, and we’re looking at flooding, both coastal and inland, and we’re also looking at severe winds. So that’s where we started.

We want to, and we have plans to, expand the tool. But as we figured, we’re going to launch this journey, how do we do that? we said, let’s start with a particular region that’s particularly susceptible to these severe weather events. And let’s look at the categories that are the most impactful to our network.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Because you do have a big network, and a lot of people depend on you. Rao, when we talk about climate models, they’re usually on this really big, global level. But over there at Argonne, you make very local-level models, down to the state, down to a couple of miles. How do you– yeah, how do you do that? How do you turn it into a hyperlocal map– a big map into a hyperlocal one?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yeah. That’s the biggest question, right? You have global climate models operating at 100, 200 kilometers. And most of the questions, like AT&T and other people, are actually asking at hundreds of meters to a few kilometers. And this has been a big gap in the way we interact with these adaptation, or mitigation, communities who are working on small scales with the global climate model.

So what we do is a process called dynamic downscaling. It’s a technical name, in a sense. Essentially, a model– you can imagine a weather forecast model that is used by NOAA– actually, it’s the same model– operating on really long timescales, not just operating on one-day or five-day forecasts, but modified so that it can operate for– what we did is we modified so it operates over all of North America for tens of years at a time. So that produces a higher resolution output.

We actually are at a resolution of about 12 kilometers per grid cell, which is approximately 10 times better than where the climate models are right now. And the idea is that, from there, you can then produce enough output from these models on precipitation variability at local scales. Then, you can run a hydrology model and coastal flooding models and do other things.

IRA FLATOW: Let me bring my audience in. Our number, 844-724-8255 if you’d like could talk about cell towers, communications infrastructure, all stuff that AT&T and other folks are thinking about and planning for. 844-724-8255, or you can tweet us @SciFri.

Shannon, this map you worked on, you say it’s a pilot. You looked at states in the Southeast. Why did you pick this region, the Southeast, to focus on first?

SHANNON CARROLL: Well, again, we knew we wanted to start small, essentially, then build after that. And so as we had the conversations about which region do you start with, it’s hard to argue that the Southeast region is particularly susceptible to these kind of weather events. So that was, really, our perspective.

We’re fortunate in the way that we have a significant footprint in terms of we cover the entire United States. But again, it just made sense to start small. And so we started with the Southeast region. 2017 was a great example in terms of what happens with climate-related events. So there was multiple severe weather events, including multiple hurricanes. And the Southeast region got hit by those, as well.

IRA FLATOW: Can you give us an idea of exactly where you’re looking at first– where in the Southeast?

SHANNON CARROLL: Well, so from our perspective, it’s the entire four states. So we’re doing Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina. And so let me describe the tool a little bit and what it can do.

So now, if I’m a network planner, if I have a responsibility for, whether it’s our buildings or our particular pieces of equipment in the network, I can sit down at my desk, I can pull up this tool, and I have a map in front of me. I can now see all the cell sites, all of the fiber layout. All of the different buildings that are associated with maintaining the network, I can see them on the map.

Now, also what I can do is click on those individual things and see what the severe weather-related events could be– so for example, coastal flooding, inland flooding. So if I have responsibility for– I’m going to make this up– five wire centers in the Southeast, or let’s say Savannah, for example, I can then click on each and every one of those and see if they’re impacted at all or will they be impacted with up to six to eight feet of flooding. And now, I have the data to make better decisions.

IRA FLATOW: And so you can theoretically, then, get your forces ready in certain areas if a storm should hit?

SHANNON CARROLL: Absolutely. And we’ve done that historically. We have a long and proud tradition in terms of disaster recovery, business continuity planning. These are things we do today. This climate model, or this climate tool, really allows us to take it to the next level and go beyond the near-term and look at the long-term impacts of climate change.

IRA FLATOW: How do the state officials you’re dealing with react to this?

SHANNON CARROLL: So the reception has been overwhelmingly positive. We have definitely received calls from folks wanting to know how they can access the data. And we, very early on in our initial press release, we talked about the fact that we’re going to make this data publicly available.

So obviously, as we engage Argonne, it’s really important that we use the data to do good old-fashioned risk management, risk assessment. But we also want to empower others to do that, as well. So we have announcements coming soon about we’re definitely going to make the underlying data that Argonne has produced for us available for everybody. It’s important that everybody is climate resilient.

IRA FLATOW: Let me go to the phones, to Charles in one of those areas– in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Hi, Charles.

AUDIENCE: Good afternoon. Thank you so much for taking my call. We’re obviously already aware and concerned about climate change here in Fort Lauderdale and especially in Miami. But my question is are there areas in the country, or particularly in the Southeast of the country, that are likely to feel less of an impact, that are safer to be?

Is it better in the Carolinas, for instance? You might hear that I’m thinking about maybe relocating, depending on how this goes. But Fort Lauderdale may not be here forever. So I’d be curious to hear the answer about where it’s safer.

IRA FLATOW: You know, we joke about it, but it is a serious question, is it not, if you want to know where to live? Let me ask Rao about that.

RAO KOTAMARTHI: So we have actually done this analysis at a good resolution of 200 meters. So once AT&T makes the maps available– there is uncertainty in this thing, so we also provide uncertainty on those things– you should be able to see which part of the region is actually less susceptible to these kinds of issues. So they way I look at what we did for this is a kind of a risk assessment for future.

So they are looking at a lot of their infrastructure, how the risk for those infrastructure may change into the future. So that’s what this does. And I think there could be a number of creative ways of using this once it is available to everybody. So I’m looking forward to it.

IRA FLATOW: When will that be? When can we look at this data? You’re saying you’ve got this down– did I hear you right– down to 200 meters?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: The flood data is around 200 meters. So the thing for me, somebody like me, that is very interesting about this is that we always talk about adaptation. Everybody says, OK, let me see if I can adapt to this change. But the cost for mitigation and policy are discussed a lot for climate change mitigation– how much does climate change policy, how much does this cost? But there is very little discussion on what adaptation costs are.

One of the cool things that AT&T’s trying to do is, what if I did this, and how would it affect my bottom line? So I think once those kinds of business case for doing this climate changes develops in the industry, that will be a bigger impact with this than a lot of other things. In my mind, that would be a huge benefit of this.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Shannon, you’re operating in some places of the country where you’re not allowed to use the words “climate change.”

SHANNON CARROLL: Yeah. So for us, our position is very clear, and we have public policies on this that I’d point folks to. But climate change impacts everybody. We recognize that. It’s going to impact AT&T. So we have an obligation, we feel, to better serve our customers, our employees, and, again, the communities in which we work to make sure that we have the most climate-resilient network possible. So it’s that simple for us.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let me go to a couple of interesting tweets coming in. [INAUDIBLE] says, does 5G– which we have talked about recently– does it offer any advantages for climate change preparedness or resilience? Shannon.

SHANNON CARROLL: So I’m not a 5G expert, so I’ll definitely stay in my lane. What I can say to that is that this tool is going to allow us at AT&T to not only assess the risk to the infrastructure that we have in the ground today but also the infrastructure we’re going to put in for 5G, the infrastructure we’re going to put in for FirstNet. And then, whatever the next new network of the future is, which we know is coming, we’ll be able to use this tool in all those cases.

IRA FLATOW: Another tweet from [INAUDIBLE] says, will the tool be easy enough for users with limited knowledge about climate science? Rao, what do you think?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yes. Yes, it should be. I think they developed a pretty nice tool.

IRA FLATOW: And I’m going to say it one more time. When are we going to get to see it?

SHANNON CARROLL: So I’ll go ahead and take that one. We’re efforting that as we speak, right? So we want to make sure that, to the point that was just made, that when we put it out there, it’s usable. And I think that’s one of the biggest challenges. There’s lots of climate data that you can find out there, but how usable is it? So we’re trying to crack that nut right now.

Obviously, with what we’re doing with it, there’s some proprietary issues in terms of our network layout. So we want to make sure that we’re able to provide the clean underlying climate data in a way that’s useful, in particular, for researchers, academics, universities, utilities– all those folks who are interested in being more climate-resilient.

IRA FLATOW: Rao, let’s talk about the many flood models that are out there. You look specifically at how coastal flooding will change in 20 years in Florida. That’s a good spot because it is so low-lying. Did you find any interesting results?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yeah. One of the difficulties of doing coastal flood or coastal surges is that climate model by itself doesn’t actually simulate a hurricane or something like a hurricane. But with our downscale model, we were able to run a coastal flood model, which is called ADCIRC. It is developed in Notre Dame.

So what we did is we had simulated a whole bunch of entire summers for the future, about mid-century, with various uncertainties, and ran this model to simulate a coastal flood-like situation. So every year, we see a few of them. So we built the statistics on that. And with the statistics for the current climate, we were able to do some uncertainty on that and also calculate what happens.

One of the interesting things we saw from these calculations is that the low end of the coastal surge actually will increase. Where you see low-impact events, they seem to be increasing. The median decreases somewhat. And the extremes on the highest events also increase a lot. So the distribution seems to be changing. All these things happen.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re saying that there’s a greater possibility of high flooding and low-level flooding.

RAO KOTAMARTHI: That’s right, yeah, from coastal events.

IRA FLATOW: And as part of– so let’s stay with Florida. Well, the whole state can’t be equally affected, but the coastal cities on the state, are they all equally affected?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yeah. Florida is interesting because they get about, I think, historically, about 40% of all hurricanes came over Florida. I think it’s even, probably, more than that. So obviously, it’s a place that these things can happen quite often. And the coastal regions get affected.

And another interesting thing is that when we did the wind analysis of, again, the risk of wind changing, Florida sees, actually, a decrease in wind speeds as you go in the future. Because the temperatures increase. And so there’s more mixing in the atmosphere, and it seems like the peak winds, actually, will decrease, on average.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios talking about coping with climate change. Shannon, do you think other companies in your business and other businesses now are having to take this more seriously and prepare as you are?

SHANNON CARROLL: Absolutely. I think if you go out there and do a little bit of research, there’s definitely companies doing things in this realm. I think what we’re doing is very unique. It’s definitely unique to our particular industry.

And we want to promote that uniqueness. We want to promote that leadership position. So again, that’s why we’re going to make this data available to everybody. We encourage everybody, whether it’s our peers or those outside the industry, to use this data.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. So Robert, a little more inland in Evanston, Illinois, though not far from a lake. So Robert, go ahead.

AUDIENCE: Yeah. Well, my question is more about how AT&T is– does it affect their different services differently? For example, traditional phone, PSTN access, and maybe rural areas where they’re still relying on some of that older technology or other similarly, like ISDN services, does AT&T deal with that differently?

Are they able to safeguard one type of service more than the other? Or are they leaving some things behind as they have to change their way of looking at the future?

IRA FLATOW: Good question.

SHANNON CARROLL: So the short answer is yes, in terms of do we have to treat things differently. And that doesn’t change from today to tomorrow. So copper wires that we have in the ground versus fiber cables, they react very definitely to water. But we rely on our network engineers, the experts that they are, to put in the right adaptation steps to address either scenario.

Again, what this allows us to do is take the great work that we’ve done traditionally in the near-term and short-term risk management planning and then expand that out to mid-century and expand that out to the probability of inland and coastal flooding. So again, all different parts of the business can use this, as well.

So if you’re in corporate real estate, and you need to put up a new wire center, or if you’re in, again, networking, and you need to put in a new cell site, you can look at those two things differently. And you have the expertise in your job to know how these different climate impacts affects that equipment. And again, we’re just giving people knowledge and information so they can make smarter climate decisions.

IRA FLATOW: If there is an area that you see might have more flooding in the future, will you not build there?

SHANNON CARROLL: We will absolutely serve our customers where they are today and wherever they will be tomorrow. That’s full-stop, right? So what this tool allows us to do, though, is, again, better serve those customers. So if our customers are in the area that is susceptible for flooding, well, now, we have a tool that’ll allow us to help maintain the networks so they can keep receiving our services.

IRA FLATOW: Last question for you, Rao. Where do you go next with this idea? How do you refine it even better?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: I’m actually looking forward to running this whole– as I said, the model we run is at a 12-kilometer simulation for the atmosphere. We now just started doing the whole thing at four kilometers. That’s a fairly large problem. [INAUDIBLE] for the entire North American continent.

So we have about 140 million grid cells and a lot of computing power needed. But we are going to get the next scale machine pretty soon, I guess. So yeah, we are looking at going a little bit lower.

At four kilometers, what happens is, in terms of physics, a important parameter for clouds called convective Ko is now no longer required. It is considered result by the model. So it does seem to make a lot of difference on how well the model does. So we are looking forward to running those simulations pretty soon.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Can you stay with us a little while longer? I’m going to take you through the break because there’s a lot of people interested who want to talk about this. Shannon Carroll of AT&T and Rao Kotamarthi, who works at Argonne National Laboratory.

Our number 844-724-8255. Do you have a question about climate change and how it affects your phone service or your infrastructure? We’ll talk about it after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking about adapting to climate change and changing climate and what companies are doing, and specifically talking today with Shannon Carroll, director of Environmental Sustainability at AT&T. And he is based in Dallas, Texas.

And Rao Kotamarthi is chief scientist of the Environmental Science Division at the famous Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois. And our number 844-724-8255. Also, you can tweet us @theSciFri. Shannon, I understand that you’ve also developed a water management application tool. Tell us about that.

SHANNON CARROLL: Sure. And thank you for asking about that. Because the tool that we’re talking about today is great and specific for climate change adaptation. But there’s also lots of other components to climate change, and one of them is water. This actually goes back several years and was done by a peer of mine– really good work– with Tim Fleming and the Environmental Defense Fund.

And what they did, essentially, is they developed a water tool that would allow facility managers to go around and essentially give themselves a scorecard in terms of how they’re using the water, how efficient the water uses was. And then, the tool then made recommendations on what they could do differently.

And much like how we’re talking about we’re going to share the climate data in the future, what we did with that tool was we then made it available to the public, as well. It’s actually maintained by a third party now, but it’s accessible to anybody and everybody to use who has facilities.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, a lot of people very interested in that. It’s an interesting topic. Let me go to John in New Hampshire. Hi, John.

AUDIENCE: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

AUDIENCE: Hey, So this is a policy question. It’s great that AT&T and other companies are planning on dealing with climate change. I’m a volunteer at Citizens’ Climate Lobby, and we’ve got a bipartisan bill in Congress called the Energy Innovation Act to greatly reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. And I was wondering if AT&T is doing anything to help Congress address the cause of climate change?

SHANNON CARROLL: So what I can say to that– again, I’m not a policy person, so I do apologize– but I will talk about largely what we’re doing in that area. So sounds like what you’re talking about is mitigation, right, so how to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases that are going into the air. And we take that very seriously at AT&T.

And to that point, last year, in 2018, we were the second-largest corporate buyers of renewable energy in the United States. We announced 820 megawatts’ worth of deals. So we are committed, definitely, to reducing our own carbon footprint. And we, obviously, encourage others to do the same.

IRA FLATOW: Rao, let me ask you something I’ve asked for, I’m going to say, 45 years. Going back to the energy crisis of the ’70s, Three Mile Island, all kinds of, I guess, infrastructure are insured. And insurance companies have a lot to say about the future of an industry about whether they’re going to insure. Are they going to insure your nuclear power plant or not, right? Are they very interested in your climate modeling?

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yes, they are interested in our product and similar products, similar kind of research that is going on. The challenge for a company like insurance company– it depends on the scale they’re operating. Somebody who is just selling a car insurance, their outlook is about five years, so they really are not worried about climate change.

But the ones that actually insure infrastructure and bigger houses and things like that, they are actually started thinking about it. And the great thing with AT&T that happened, the conversation we need to have with the insurance company, is that with AT&T, the first three, four weeks, we just kind of figured out what they think climate change is and what we think they need. And it actually took a lot of discussion to come to a common ground, that OK, what you guys are talking about is how will the water depth change in some grid?

So I think that kind of conversation has not happened, at least for me, with the insurance companies. I talk to a lot of them. And they are still at this place they are trying to find out how they manage this risk.

And because the risk tables they use are based on historical climate data, so how do I act to that? And what is the competitive advantage in that for me if I increase my rates because climate is changing, and nobody else is doing?

IRA FLATOW: So you’re giving them a new tool that they can use that they didn’t have before.

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Yeah. So they think of this as a product innovation, somewhat.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Well, we’ve run out of time. A great topic of discussion. Thank you both. Rao Kotamarthi is chief scientist at the Environmental Science Division at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois. Shannon Carroll, director of Environmental Sustainability– I’ll get that word right– at AT&T, based in Dallas. Thank you both for this great discussion.

SHANNON CARROLL: Thank you.

RAO KOTAMARTHI: Great. Thank you.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.