A High School Student Invented An Affordable Brain-Reading Prosthetic

06:57 minutes

Artificial limb technology has come a long way since the first prosthetic—a big toe made of wood and leather developed in ancient Egypt.

Today’s cutting-edge robotic limbs use mind-control and even give users a sense of touch, helping them feel sensations like a warm cup of coffee or a mushy banana. Still, these state-of-the-art prosthetics often involve invasive brain surgeries and can be exorbitantly expensive.

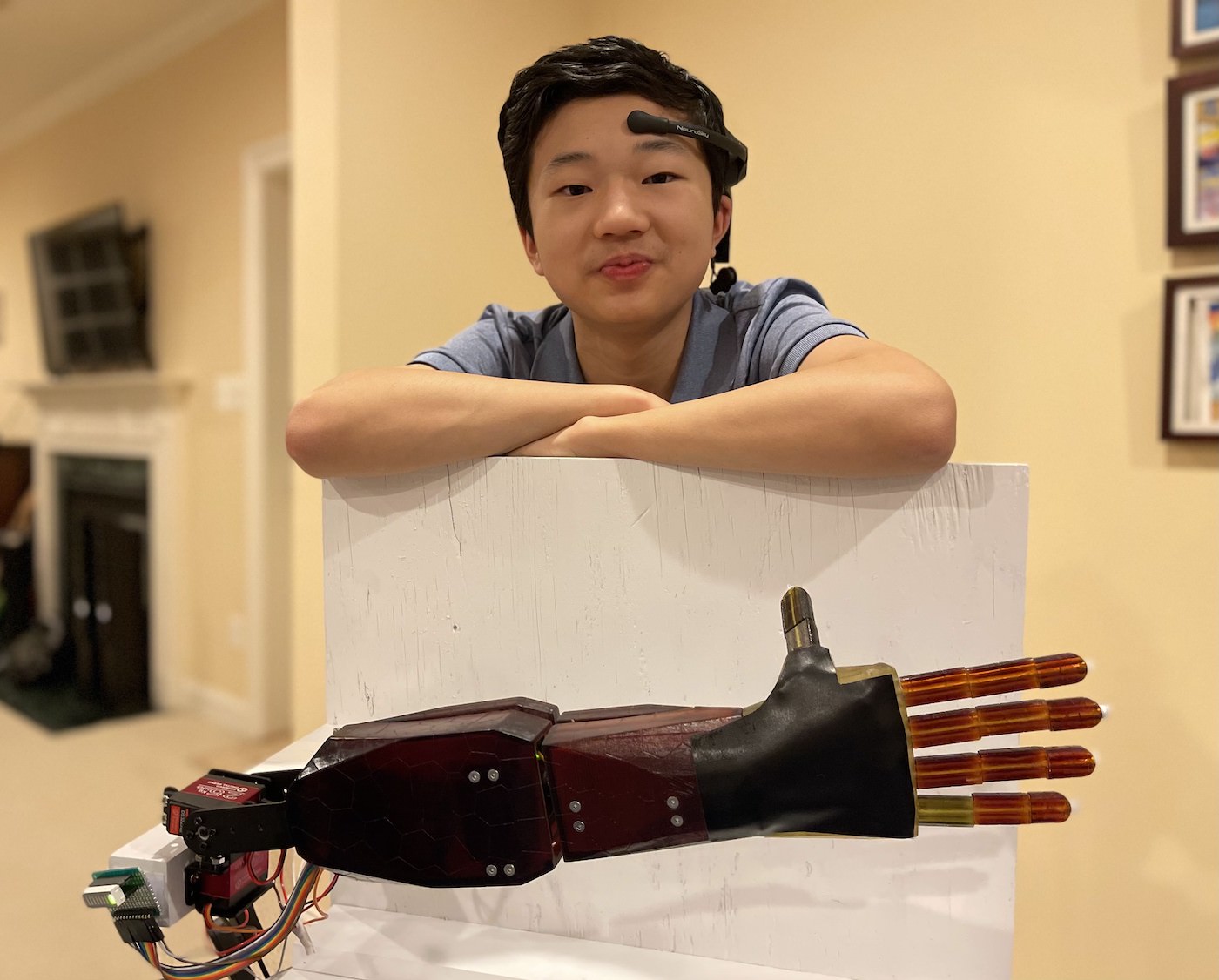

Hearing of these issues, one teenager set out to create a solution. Seventeen-year-old Benjamin Choi has developed a non-invasive, affordable prosthetic arm. His Star Wars-inspired technology reads a user’s mind with only two sensors—one on the forehead and the other clipped to the earlobe. And he doesn’t plan on stopping there. He sees his work in artificial intelligence expanding to help ALS patients, wheelchair users, and beyond.

Ira speaks with Benjamin Choi from McLean, Virginia about how he developed this arm and what it means to be a young innovator.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Benjamin Choi is a student innovator based in McLean, Virginia.

IRA FLATOW: Prosthetic limbs have come a long way since the very first one from ancient Egypt. By the way, it was a big toe made of wood and leather. Now, the most high-tech devices are mind controlled, translating brainwaves into movement. But these state-of-the-art prosthetics often involve invasive brain surgeries. And they come with a hefty price tag that can exceed hundreds of thousands of dollars, making them wildly inaccessible for most people.

But now, 17-year-old inventor Benjamin Choi is doing something about it. He set out to create an affordable mind-controlled prosthetic. Ben’s story is part of our series of impressive young inventors who are taking on big problems.

Ben hails from McLean, Virginia. Ben, welcome to Science Friday.

BENJAMIN CHOI: Hey, thank you so much for having me. I’m so excited to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Tell me what inspired you to create a cheap prosthetic arm.

BENJAMIN CHOI: I was initially inspired when I watched a 60 Minutes documentary on brain-controlled prosthetics. I was super amazed by the amazing potential impact of this technology to improve lives, but alarmed that the form of mind control used in this documentary required this really risky open brain surgery, and costed over $450,000.

So after conducting a lot of extensive research into the many shortcomings of current upper limb prosthetics, I was inspired to come up with a non-invasive solution.

IRA FLATOW: Can you walk me through the basics of how it works?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Sure. So my solution employs this electrode that’s placed on the center of your forehead. And essentially, all the time when you’re awake, you have these electrical signals. And essentially, the underlying theory behind my project– which is that these electrical signals are correlated to your underlying brainwave activity– and so if we can decipher these electrical signals, we can ultimately figure out what you’re thinking and then use that to control a prosthetic arm.

The problem with this is that these electrical signals on your forehead– because they’re noninvasive, because they’re one step removed from the actual brain itself– they’re very complex and hard to decipher. And so what I use to decipher these very complex electrical signals was this new AI algorithm that I created. I collected brainwave recordings from this wide slate of human participants, and then I used those recordings to train this new artificial intelligence model that essentially learned to decipher those electrical signals and figures out what you’re thinking,

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So were you successful in controlling a prosthetic using that kind of technology?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Yes. The algorithm is very effective. The structure of the model actually is that it’s designed to tailor itself to each individual user over time. And so the more brainwaves it gets from a user, the better the AI gets at reading those specific brainwaves.

IRA FLATOW: So your AI is basically teaching itself– it’s getting better the more it gets used?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Yeah, exactly. Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: And what kinds of prosthetics can it control now?

BENJAMIN CHOI: So right now it’s just optimized for this upper limb prosthetic arm. But definitely one of the things I’m super interested in exploring in the future is this AI algorithm for brainwave interpretation could have so many more applications beyond just upper limb prosthetics. I think it could be used for so many different brain-computer interface applications, like for example, helping patients with ALS communicate.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Now, we have heard of other people working on such projects. What is your competitive advantage in the way that you do this?

BENJAMIN CHOI: One of the advantages of my system is, because I’m using AI to interpret brainwaves and fill in some of the gaps, the system can work with very little data. So I actually only need one sensor on the forehead and then one baseline sensor, versus conventional EEG setups require hundreds and hundreds of electrodes, making them really impractical for everyday use.

In fact, my system has achieved the highest-ever accuracy on interpreting EEG data from just one sensor. It’s at over 95%. The previous best was around 73.8%, I believe.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. So why do you get such better results?

BENJAMIN CHOI: I think the main thing driving the success is not only the fact that I’m using this AI algorithm, but this AI algorithm I’ve developed has a very special structure as well. Essentially, what I’m doing is I’m taking different AI models that have completely different structures, and I’m giving them each the same packet of data. And each of these new AI models essentially outputs their own prediction independently of the other models, and then they conduct like a bit of a vote.

And so what I’m trying to do here is I was trying to fill in the potential gaps that one AI model might have at predicting brain waves through these other models that approach the problem completely differently and think in a completely different way.

IRA FLATOW: So you haven’t invented a different kind of sensor– you’ve actually created much better AI to interpret the brainwaves. And what’s your next step with this?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Sure. So I definitely want to make this something that amputees can actually use and see this all the way through. One of the things that’s been really inspiring for me is I’ve been able to work with an upper limb amputee who has provided a lot of feedback on my work. Which has been super cool and definitely really motivating in this process.

Next, I’m definitely hoping to test this device on actual upper limb amputees and continue to get more feedback, and so I can keep improving it until it can be something that people can actually use.

IRA FLATOW: How has the response been to what you wanted to do? Has it been supportive, or have people sort of said, oh, yeah, go ahead, try to do that?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Yeah, I think the response has been very positive. Especially I’ve had so many members of the amputee community actually reach out and talk to me and give feedback and advice that’s been just so helpful for me throughout this process. And so, yeah, I think I received a lot of support from them.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I understand you’re going to Harvard next semester. Congratulations. Are you going to be continuing your work there?

BENJAMIN CHOI: Yeah, definitely. There are tons of ways I really want to continue to improve this project. One is specifically with the actual physical model of the prosthesis itself. Designing it was a very lengthy process, but there are still so many ways I’d like to continue to upgrade the design. And some of these will require investments in new materials or a new socket fitting that I really want to do.

I was fortunate enough to receive a lot of funding from this company in California, polySpectra, who really helped me on the material side. But still, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done in creating a socket. And also, another thing is the clinical trial process is a very lengthy process. It can be very expensive. And so that’s another thing I would really like to get more funding on. And then, just, of course, continuing to improve my algorithm– advance that even further.

IRA FLATOW: Benjamin Choi, inventor and student, in McLean, Virginia, heading to Harvard this coming semester.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Mackenzie White was Science Friday’s 2022 AAAS Mass Media Fellow. Her favorite things to talk about are space rocks and her dog, Rocky.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.