Student Scientists Tackle Real World Questions

17:24 minutes

This week, science students gathered in Pittsburgh for the finals of the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, a competition founded by the Society for Science and the Public. Nearly 2,000 students from 75 countries came to present their projects—and they are far from the exploding volcanoes or paper-mache models of the Earth that might come to mind.

[On being a scientist (and a patent holder) at any age.]

Ira chats with two of these finalists, including Everett Kroll, a junior from Stillwater Area High School from Woodbury, Minnesota, who created and tested an affordable 3D-printed prosthetic foot, and Alyssa Rawinski, a junior from Monte Vista High School who studied the feasibility of using mealworms to recycle plastics.

SciFri continued the discussion with Kroll and Rawinski to learn more about them and their projects. Read below!

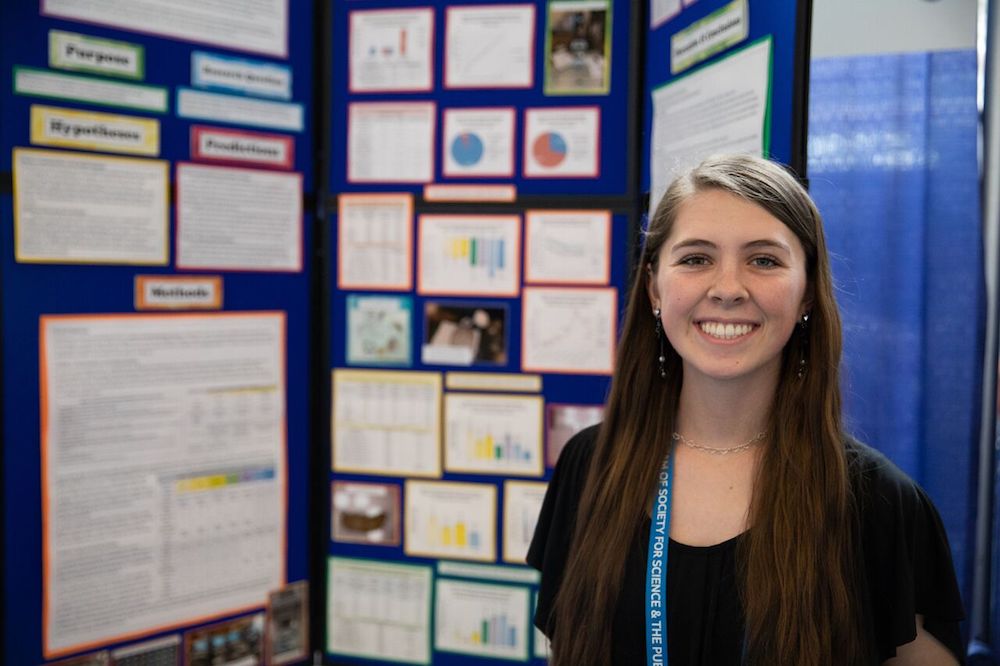

11th grader at Monte Vista High School in Colorado

Briefly, what is your project?

The goal of my project was to try to find a more eco-friendly way to decrease the plastic accumulation by using mealworms to biodegrade plastics. My study analyzed polystyrene and two plastics that haven’t been tested, polypropylene and low-density polyethylene.

Why did you decide to look into this question?

I was hearing a lot about the damage that was being caused by plastics in the ocean. It’s harming ecosystems and almost 300 species in the ocean and I wanted to see if I can do anything to prevent that, even though I live far away from the ocean. Since plastics that end up in the ocean come from land, that means that the solution must also start on land, and that’s how I thought I could help find a solution and make a difference.

[The next all-natural recycling solution? An enzyme.]

What was one surprising thing you learned during the experiment?

The biggest surprise was that mealworms actually do consume multiple types of plastic. In general, I was surprised that these mealworms eat a lot of different things—and they’re kind of stubborn sometimes and somewhat unpredictable.

In my initial setup, I was using plastic drawers to contain them and it had tin foil dividers within the drawers to separate the worm groups, but they started chewing on the tin foil. I didn’t want that so I had to move them into solo cups. Another thing I wanted to provide was moisture to the worms by putting wet pieces of pumice into each of the cups. But after they chewed on the tin foil I decided to test it out, and they chewed on the pumice as well. So they weren’t working with me really well, but I eventually figured it out [with the solo cup setup].

Another big surprise was that having a mixture of plastic and potato was the most effective. Potato provided nutrients to the mealworms so they were healthier, but they still choose to consume the plastic.

[How Jane Goodall got her start.]

If you could have dinner with any scientist (living or dead) who would it be and why?

I’m going to say Jane Goodall right now because she is really passionate about her work and she’s been doing it her whole life. She works with animals, which I really care a lot about. She also knows a lot about her field and I think she can really inspire me to find what I’m passionate about because I’m still looking for that.

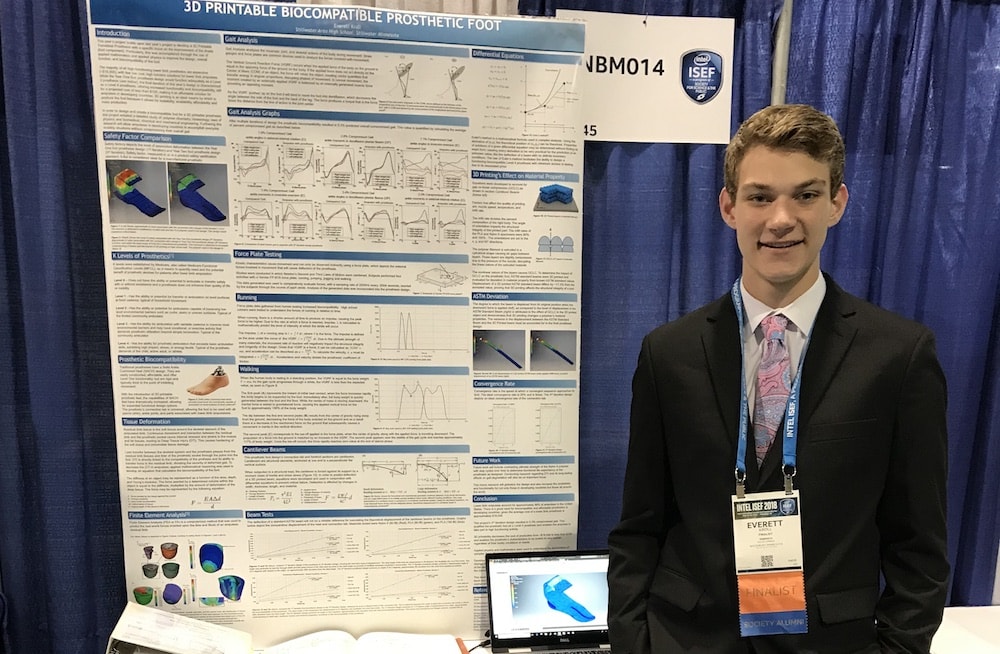

11th grader at Stillwater Area High School in Minnesota

Briefly, what is your project?

I created a level four prosthetic that is 3D printable for around $10, a fraction of the exorbitantly high price [for prosthetics], so as to reach a wider range of people. This was done through applied physics and mathematics to create and achieve a higher level of biocompatibility so as to be more beneficial for the amputee wearing it.

A level four prosthetic is the highest of the levels of lower limb prosthetics. Level four is capable of Olympic activity, so anything that is running, jumping, any high strain activity with high force. It also has the most biocompatibility and the least effect on gait degradation.

Why did you decide to look into this question?

I got really interested in 3D printing at my school’s makerspace, which is a place with 3D printers and CNC machines—just a place where kids can express their curiosity and start their engineering prowess… One day I was just looking up 3D-printed projects and I came across a 3D-printed hand. And I started thinking about hands and how much of the world this can affect. I looked into different statistics on prosthetics and I found that prosthetic feet—more specifically transtibial prosthetics, which is right below the knee—are the most common amputations in the world. That was my project last year project. This year, I just focused on the foot so that I could reach a larger range of people, because if you have an amputation below the belt you’re going to need a foot, and since lower leg amputations account for a vast majority of prosthetics in the world, it was a great place to further my research. I’m just pretty curious about engineering and I love 3D printing so it was just this kind of great crossroads of different fields I’m interested in.

[For these bio-bots, squishy is superior.]

What was one surprising thing you learned during the experiment?

How much failure can come from something that you are extremely confident in. The first design I ever made I was like, “This is going to be the premier design. This one is going to work. I’m so excited.” I did so much research, and then I stood on it and it shattered and it cut my leg. That was very surprising to me. I thought it was going to be a lot easier than it was.

It’s just surprising how much engineering goes into something that looks so simple, but really is extremely complicated. Like with my [prosthetic] foot, there’s no moving parts, there’s no electricity, there’s no motor or nothing like that. It seems very simple, it’s just a shape that kind of looks like a foot, but you have to do more by multivariable calculus, and linear algebra, and just run calculations, and all these different crossroads of very complex principles and engineering goals and situations—and a simple problem becomes a lot more difficult. It’s just one shape, a solid shape, and it took me over 20 months to make.

If you could have dinner with any scientist (living or dead) who would it be and why?

Immediately when you said that I started thinking about how I could work around it, like maybe I could have dinner with like five different scientists, like speed dating. So like only three minutes with one scientist… Either, a young Stephen Hawking when he was still at Oxford, just because when he was in his earlier work he was very philosophical and I think getting into a conversation about the meaning of certain life through science would be kind of cool. Or, a middle-aged Albert Einstein after the total eclipse when his theory [of general relativity] was proved. I think he’d be very excited about it.

But I think my final answer would be Neil deGrasse Tyson because he is just very philosophical and he is just a brilliant man and capable of explaining almost anything I can be curious about. I think he’s very famous for being just this very open and happy personality that’s very jokey and I think we’d get along very well.

These interviews have been edited for space and clarity.

*Correction 5/21/2018: A previous version of this article misstated part of Rawinski’s experimental setup. She used “pumice,” not “humus.”

Alyssa Rawinski is an 11th grade student at Monte Vista High School in Monte Vista, Colorado.

Everett Kroll is a 11th grade student at Stillwater Area High School in Woodbury, Minnesota.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. If you think back to your high school science fair, there were probably a few baking soda volcanoes. Remember that one? Or maybe a diorama of the Earth. Well this week, students from 75 countries came to Pittsburgh to present their projects as part of the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair.

And these were the finals. And the students have– they’ve stepped up their game. They’re not doing those little pipe cleaner or paper machine models. Not one in sight. These students were using carbon nanotubes, AI neural networks, 3D printers to investigate some pretty complicated questions. And these kids are all right. And we have two students here joining me in the studio here in Pittsburgh to talk about their projects.

Let me introduce them to you. Alyssa Rawinski is a junior at Monte Vista High School in Monte Vista, Colorado. Welcome to Science Friday.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Thank you so much. It’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Everett Kroll is a junior at Stillwater Area High School in Woodbury, Minnesota.

EVERETT KROLL: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you both, both of you. Are you excited to be in Pittsburgh for the finals?

EVERETT KROLL: Yes, very.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: It’s exciting. Now, let me talk to you first, Alyssa. You tested a really interesting way of recycling plastic. You fed three different types of plastic to mealworms.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: That’s exactly right, yes.

IRA FLATOW: Who ever thought of that?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I was reading a lot of information about how plastic was affecting species in the ocean, damaging ecosystems. I really wanted to do something about that. So through research, I found information about the mealworm and its ability to biodegrade polystyrene, which is Styrofoam. And I wanted to look deeper into that, and explore other plastic types.

IRA FLATOW: So whoever thought worms would ever eat plastic? It’s amazing. You probably didn’t either.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: No, I didn’t.

IRA FLATOW: It doesn’t hurt the worm, does it?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: No, I found that feeding them strictly plastic didn’t kill more worms than just feeding them potato. However, it did slow down their life cycle a bit. However, you can prevent that by providing a healthy food source, such as potato to the mealworms, as well, and they will still consume plastic.

IRA FLATOW: Now, how come they can consume plastic and I can’t do that? What do they have going for them?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: There’s a special type of bacteria that they have in their digestive system that breaks down the molecules in plastic.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, we talk about the microbiome a lot on Science Friday. So they must have a really interesting microbiome in their own little bodies.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yes, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Are you interested in pursuing that, for learning what that’s like?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yeah, definitely. I’m really excited by this.

IRA FLATOW: Could you imagine then scaling this up for all the– we have all this plastic pollution, right?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Right. So to give you an idea, a dump truck of mealworms could consume an SUV’s weight in polystyrene plastic in one year.

IRA FLATOW: So that– oh, wow.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: A dump truck of mealworms–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Can eat an SUV of polystyrene.

IRA FLATOW: Last year, you had a project where you studied western snowy owls.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Snowy plovers.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, excuse me.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: What were you trying to find out in that project?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I was looking at their nesting characteristics. They’re a threatened species, so it’s really important to save their preferred nesting area. And I was trying to figure out exactly what they liked.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, so you’re drawn to environmental–

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Definitely.

IRA FLATOW: –topics. Because?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I think we really need to be compatible with everything on this planet. And as far as– working together to help the environment is really important.

IRA FLATOW: All right, we turn to you, Everett. You printed– 3D printed a prosthetic foot.

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Your interest came from?

EVERETT KROLL: Just discovering a need for it, I guess. Last year, I developed a transtibial prosthetic, which is from the knee down. And this year, I just tried to remedy both the two largest problems associated with prosthetics in the world– their level of compatibility and the price. So it was really just carrying over my work from last year into this year.

IRA FLATOW: So how do you how do you try to improve prosthetics? What were the key questions you were trying to tackle on this?

EVERETT KROLL: Well, what areas affect gait, which is how we walk. Just different factors that go into the specimens associated with humans and how they walk. And then bringing the materials that are used for prosthetics into a more viable prosthetic line.

IRA FLATOW: So you looked at the prosthetics we have around and said, I can make a better one. In what way? In what way is it better– your idea?

EVERETT KROLL: A lot of different material property is accounted for in the prosthetic. So since it’s passive, which means there’s no really moving parts, I have to use my knowledge of material science and physics to really bring out the hidden talents of material property. And it stores potential energy better. It lasts longer. It is a lot cheaper to produce. And it can do just about anything any other prosthetic on the market can, so it’s better bang for your buck, I guess.

IRA FLATOW: So you had to sit down and actually do the math.

EVERETT KROLL: Oh, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: What kind of math are we–

EVERETT KROLL: Differential calculus, multivariable calculus, linear algebra, all different types of high level math that–

IRA FLATOW: You’re a junior in high school, right?

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: How did you get the knowledge to do this math?

EVERETT KROLL: Self-taught. Just kind of sat down at my desk and read a lot of different textbooks, and just read online.

IRA FLATOW: Well, have you been able to interest any prosthetics makers?

EVERETT KROLL: I’ve done a lot of work with different hospitals, and I’ve worked at the hospital back home, Fairview Medical Hospital, and gone into different prostheticist’s offices, and stuff like that. But I don’t think it’s, at this moment, the best way to distribute it right now.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Now you’re a runner on the track team?

EVERETT KROLL: Cross country team.

IRA FLATOW: Cross country, excuse me. So you must have studied how people move and run on the track team.

EVERETT KROLL: I actually used my cross-country brethren, I guess– our teammates for a running study.

IRA FLATOW: Does that mean guinea pigs?

EVERETT KROLL: Oh, yes. They actually ran on a force plate and it was kind of funny. They had to sign an IRB form, which is kind of consent form.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, investigational research.

EVERETT KROLL: I had to assure them that they would not be cut open with anything. And that was kind of funny just to see how much they can get scared over just running, which is something they do every day. But it’s just a great way to involve other people in science.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask both of you. Let me ask Alyssa first. What did you learn about yourself when you did this?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I learned that I really like discovering new things. And it’s really fun to do new things, and learn from your mistakes, especially. There were–

IRA FLATOW: Mistakes? Yeah, we don’t reward mistakes, do we? But you have to learn– when you do science, mistakes are what it’s all about.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yeah. This project really did help me figure out that I do want to go into behavioral studies in the future. And, yeah, this was a really exciting project for me.

IRA FLATOW: And Everett, what surprised you the most when you were doing this?

EVERETT KROLL: You learn nothing from doing something right the first time.

IRA FLATOW: Say that again.

EVERETT KROLL: You learn nothing from doing something right the first time. Everything in science is done either through failure or learning from failure. And I failed a lot in my project. My final iterational design is my 54th iterational design.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

EVERETT KROLL: And–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

EVERETT KROLL: It’s hard to keep going after you put 20 hours into one design, and it just shatters.

IRA FLATOW: But you did. You kept going.

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah. If you have a goal that you’re trying to get to, and you really just keep focused on that next horizon or that next hill, the things you can accomplish are just amazing. So just pushing yourself or identifying that when you fail, it’s not necessarily the end, just another way to improve.

IRA FLATOW: You know, that is the definition of research.

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: You know, there’s the search– that’s the first part. And then there is the research.

EVERETT KROLL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And you keep researching it all the time to get it right.

EVERETT KROLL: Very, very true.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Being a geek is one of our highest honors around here, I want you to know. I have pocket protectors, if you know what they are. You don’t look geeky like I am. I mean, how do you– do your fellow students look at you as geeky kids? Yeah? You’re shaking yes? You’re nodding?

EVERETT KROLL: Yes, definitely.

IRA FLATOW: Alyssa, what do you mean? How do they treat you differently?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I don’t know if they treat me differently in a bad way. It’s just they know that I’m a big science fan, and I’ll do all I can to work hard and do the best I can.

IRA FLATOW: Does any of that rub off on them?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I would hope so. I would like that.

IRA FLATOW: And Everett?

EVERETT KROLL: I would say, definitely my friends view me as a nerd. I am captain of my robotics team. And I’m in Science Bowl, Science Olympia, all sorts of different, geeky things, I guess. And I love being a person that can have an in-depth conversation about the string theory on the bus. So just anything that is science related, I’m there. So I like it a lot.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think adults are interested enough in science? Do you think they appreciate– especially in the environment. You’re very much in doing environmental things. Do you worry that there’s not going to be an environment when you like they have when you grow up?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Definitely. That is my biggest worry. And at this point, I’m doing all I can to not only educate the adults through science fair, but most importantly, the students that are my age and younger than me. I think we are the generations that are going to make a difference.

IRA FLATOW: We old people like me, we’re looking to you, teenagers. There’s an old saying that we borrow the future from our grandchildren because that’s their future and we’re using it up. And I see that you’re shaking your head also.

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Do you do you feel motivated? Do you feel like that it’s part of your mission is to try to save your future?

EVERETT KROLL: 100%. You need to protect what is going to be there for you later. So especially an environmental scientist, I think that one thing that’s being greater– or the focus on is being increased over the past two years or so, which is really important. And it’s definitely a necessity, or it’s necessary for it to be increased, or have a higher importance.

IRA FLATOW: And how can you as teenagers do something about it?

EVERETT KROLL: Open your mind.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Science fair.

IRA FLATOW: How about opening your mouth and talking about it?

EVERETT KROLL: Talk about it.

IRA FLATOW: Talk about science.

EVERETT KROLL: Learn about it. Don’t be afraid that it doesn’t– if you don’t understand it, try to understand it. And if you don’t, ask somebody.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking with two of the very lucky people to be involved in the Science and Engineering Fair, the Intel Science and Engineering Fair here in Pittsburgh, Alyssa Rawinski and Everett Kroll. Do you have heroes? Do you have any scientists whom you look up to? I mean, when you go through this, you talked about failure. And failure is very big in science.

EVERETT KROLL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: You have a hero you would name?

EVERETT KROLL: It’s hard to pick one.

IRA FLATOW: Well name a few.

EVERETT KROLL: There’s the easy answers, the big ones, like Hawking, Einstein, just anybody really that’s been named. All sorts of scientists that, if you think about it, the ones that everyone knows, they’re not the ones that did it right the first time.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

EVERETT KROLL: Einstein submitted his special relativity paper, I think, several times.

IRA FLATOW: Yes he did.

EVERETT KROLL: You can’t get it right in the first time. And that’s not the best thing. So you got Thomas Edison who figured out 1,000 ways not to make a light bulb.

IRA FLATOW: That’s right– eliminated everything that didn’t work.

EVERETT KROLL: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Got down to something. That was the brute force method. Alyssa, do you have someone who?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Well, I agree with Everett, definitely. For me, it’s more inspiring the support that I have at home from my teachers and my family. They’re big supporters, and they really do inspire me.

IRA FLATOW: What is it like this week to be part of the science fair? And finally, you’re geeky working by yourself in your high school, and suddenly you’re here with hundreds of other kids who are like you. What is that like?

EVERETT KROLL: It’s amazing. You’re joined by your fellow nerds. You’re no longer a nerd. You’re an average kid, which is a little bit scary. At first, you’re not the kid that can recite pi. You’re that kid that can’t recite it as much as the next kid next to you. So it’s a really great experience just to see and be with people that are just as excited and passionate about your passion as you are. So it’s a great thing.

IRA FLATOW: Alyssa, yeah?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I agree, completely. It’s so much of a learning experience, and meeting new people, and, yeah, being with people just like you is really amazing.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you’re both juniors. You have to think about going to college next year. What are you thinking about? What do you want to study? Where do you want to go? Alyssa, I’ll also ask you first.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I’m still open to ideas. I’m leaning towards biology or zoology. And possibly in state where I’m from, Colorado, but I’m keeping my options open as long as I can.

EVERETT KROLL: I would like to go into mechanical engineering, physics, or applied mathematics. I like rigorous courses, so I definitely get that with engineering.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have a school that you’re looking at?

EVERETT KROLL: I’m looking at a lot of different schools like she is, just keeping my options open. But I do like Northwestern so far.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, yeah. Are you able to talk to your parents about what you do? Do they understand the level of what you’re working at?

EVERETT KROLL: Yes, my mom can recite Young’s modulus, and everything that is associated with material science because she’s read my paper so many times.

IRA FLATOW: She’s a scientist?

EVERETT KROLL: No. She’s an accountant. But she is brilliant, and I appreciate her very much.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, you can see where you get it from. And then Alyssa?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: My parents are big helpers with my science fair project. My dad is a retired soil scientist.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, is that right?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: And so my mom is a wildlife biologist, so they really– they’re excited by my work, as well.

IRA FLATOW: So that’s where your interest in the environment comes from?

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. If you could do anything, any career, let’s say forget about college, I could award you a career. What would you want to do? Where would you like to study? Just what you’re doing.

ALYSSA RAWINSKI: I would like to study all over the world.

IRA FLATOW: And you?

EVERETT KROLL: Probably at 3M back in Minnesota.

IRA FLATOW: All right. I hope they’re listening. I hope everybody’s listening. It’s all the time we have. I want to thank both of you. And good luck to you both, Alyssa and Everett. Alyssa Rawinski, junior at Monte Vista High School in Monte Vista, Colorado. Everett Kroll, junior at Stillwater Area High School in Woodbury, Minnesota. Both finalists in the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair.

That’s all about time we have for today. Our thanks to 90.5 WESA in Pittsburgh for hosting us today. And to WESA’s John Sutton, Ross Lloyd, Tom Hurley, Helen Wigger, Terry O’Reilly, Nick Wright for the help in putting on our program. And join us tomorrow night at Carnegie. We don’t know how to say– it’s Carnegie or Carnegie– we’ll say it both ways– Library Music Hall for a special live taping of the show. Still a few tickets left sciencefriday.com/Pittsburgh.

And if you missed any part of the problem, you always hear our podcasts. Also, where everyday is Science Friday, we’re on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and you can ask your speaker to play it at any time. Have a great weekend. I’m Ira Flatow in Pittsburgh.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.