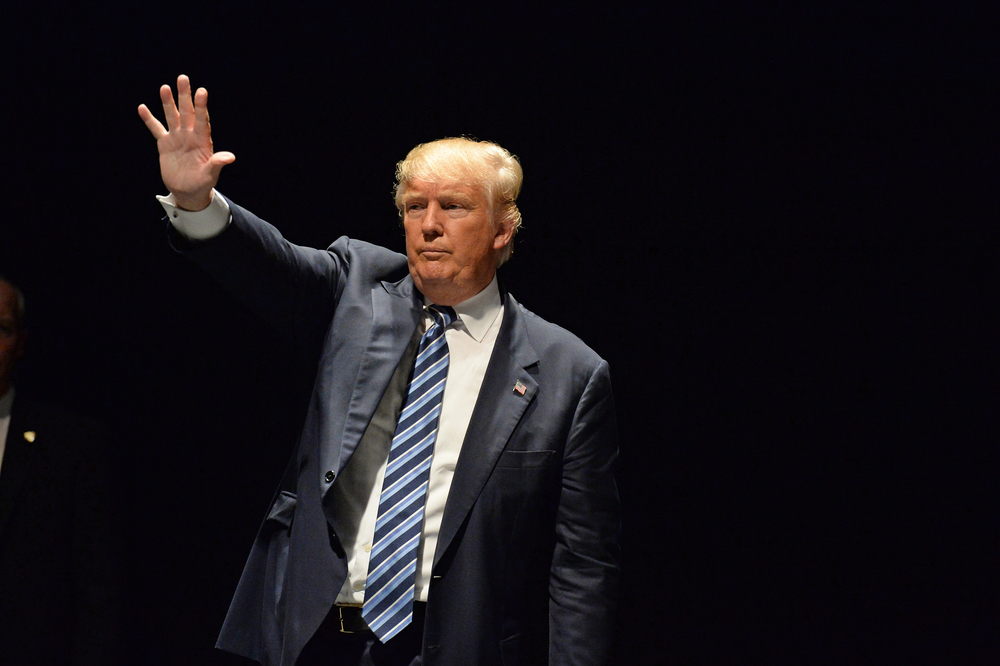

Special Coverage: How Will Scientific Research Fare Under President Donald Trump?

46:58 minutes

President-elect Donald Trump hasn’t said much about the future of science policy or funding in his administration, and much remains unknown. But there are some clues, both in the people he’s nominated for cabinet positions so far—such as his controversial EPA nominee, Scott Pruitt—and in the priorities of Republicans in Congress.

On the heels of Friday’s inauguration, Science Friday presents an hour of special coverage on science under the Trump administration. Ira Flatow talks to a panel of policy experts about what we know so far and what we can realistically expect. Plus, what might Congress do about politically controversial work on climate change or fetal tissue, and to what extent will scientific research guide policy decisions? And how might funding for basic research be allocated?

Rush Holt, the CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a former physicist and member of Congress, helps break down the potential actions ahead.

Also joining the conversation are:

Rush Holt, a former congressman, is CEO of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the executive publisher of the Science family of journals. He’s based in Princeton, New Jersey.

Jeff Mervis is a senior correspondent for Science magazine and longtime reporter on science policy. He’s based in Washington, D.C.

David Goldston is director of government affairs at the Natural Resources Defense Council in Washington, D.C..

Susan Tierney is a senior advisor at The Analysis Group and is Former Assistant Secretary for Policy at the U.S. Department of Energy. She’s based in Denver, Colorado.

Sara Reardon is a biomedical research and policy reporter for Nature News in Washington, D.C..

Shaughnessy Naughton is the founder of 314 Action. She’s based in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. With the ushering in of the Trump administration, we’re now left to wonder in what direction America’s science and technology will head. Can we expect weakening of clean air and water standards, a pullback from the Paris Climate Agreement? Will we see steady investment for the NIH and medical research? Will embryonic stem cell research be limited, as it was under Bush? Will NASA be prohibited from global warming research, but perhaps see more investment in space exploration? So many more issues.

So we’re setting aside this entire hour of the program to look at what we can and cannot yet say about science under the Trump administration. If you’d like to join our conversation, what are you wondering about how scientific research and policy could change under the Trump administration, give us a call. Our number, 844-724-8255. 844-SCI-TALK. You can also tweet us, @SciFri. Let me start off with my first two guests this hour.

Rush Holt is the chief executive officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the AAAS, former Democratic Congressman from New Jersey. He’s also a physicist, and he’s here in our New York studios. Welcome. Good to see you in person.

RUSH HOLT: Great to be with you again, Ira.

JEFF MERVIS: Jeff Mervis is a senior correspondent for Science magazine. He’s been covering science policy for more than 30 years. He joins us from Washington. Welcome back to Science Friday, Jeff.

JEFF MERVIS: Thank you, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Rush, let me begin with something we were chatting about before we went on the air. And that is about this idea of fact based science in Washington. What do facts mean in Washington? You say there’s a tradition going way back, decades, that you’ve been part of or had heard about years before.

RUSH HOLT: Well, you were talking about where we find ourselves now. And I must say, in recent months, the level of uncertainty and even anxiety among scientists is higher than I’ve ever seen.

Now of course, there’s uncertainty because, at any transition, there’s uncertainty. And because the incoming president has been cryptic in his statements about science. And there are some sort of representative issues, like climate change and so forth, that are– the don’t sit well with scientists. But I think what really bothers scientists, many of us, and the reason they’ve been calling me daily from other science societies, from our membership at AAAS, and so forth is that they don’t like what they see is happening to evidence.

The attitude toward evidence is, and I prefer to use “evidence” rather than “facts.” Evidence, you know what you’re dealing with. Facts, you hope the evidence builds up to be accepted as a fact. So I think it is this uneasiness that we see today. And it’s not new.

It didn’t begin with the fake news of the past months and year. It didn’t begin with the election of Donald Trump. It didn’t begin with cabinet officers who deny climate change, or at least are skeptical about the evidence. It goes way back. And I think what you’re asking about is an experience that I had 3 and 1/2 decades ago.

I was a AAAS American Physical Society fellow. This is a program AAAS has run for many decades now to place PhD level scientists in all three branches of the government. There are about 250 such Fellows every year.

And way back then, in the early ’80s, a group of us scientists were in the orientation session for the year-long fellowship. And one of the speakers said, now, you have to understand that here in Washington, facts are negotiable.

And then the next day, a completely separate speaker said you have to understand that here in Washington, we treat facts differently. And the third day, a different speaker at our orientation said, you have to understand that here in Washington, perceptions are facts.

IRA FLATOW: But now you’re saying it has reached a culmination over all those years?

RUSH HOLT: And I really think what we see now, you know, the really willfully fake news, not mistakenly factually wrong news, but willfully mistaken, policy makers who are willfully excluding the research based evidence from their policy making, it’s gotten worse. And so when we talk about the erosion of the appreciation of science, that’s what I mean, anyway. And it’s not new, but it’s come to a head now, almost a culmination.

IRA FLATOW: Jeff, how do you react to what you’ve seen so far in actions by the Trump administration now, and the different committees that are being set up?

JEFF MERVIS: I think it’s helpful to think of what a president means when he uses the word “science.” And I use “he” because so far, we’ve just had male presidents. So Obama, in his inaugural nine years ago, said he would restore science to its rightful place. So when a president or a politician uses the word “science,” he’s really talking about three things.

One is money. How much funding research will get. There’s about $150 billion that gets divided. We can talk more about that.

There’s people. Those are the people who head the agencies that pass out that money. And then, there’s policy. And that includes regulations, everything from deciding how to regulate the new gene cutting tool called CRISPR to whether to go to the moon and Mars.

And it’s important, I think, whenever you talk about the issues that Rush had mentioned to sort of remember which of those categories may go. Sometimes they intersect. If I can use just a very short example, the Census Bureau, which is the government’s leading statistical agency, conducts something called the American Community Survey. It’s part of the census. It used to be part of the every 10 year census. Now, it’s done every month.

It collects lots of information. Some politicians object to the questions they feel are intrusive, like asking when you’re going to leave for work in the morning. They say, why should the government know that? Well it turns out the reason you need to know that is for urban planners and transportation experts and developers to develop a transportation system that can accommodate those commuters.

So that’s a question of policy. Then, you also have the fact that the director of the Census Bureau is an appointee. And that position is now open, although the current director is staying on until a person is named. And then, you have the money.

Every 10 years, the census budget jumps up by some $10 billion because the census is very expensive. And a lot of budget hawks say, why are we spending all that money? Let’s just cut it.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

JEFF MERVIS: So that’s a case where you have all three of those factors in play. And if you want to see a litmus test for what’s going to happen, that’s a good one to watch in the months ahead.

IRA FLATOW: We will watch for it. Rush, President Trump made a few references, a few references, to science directly in his inaugural address, including to the technologies and industries of tomorrow, infrastructure, American-first hiring approach. What’s your impression of those science references and where they might take us?

RUSH HOLT: Well, I would say that the inaugural address was really devoid of science, as has been the transition, the transition team. He said, we’ll unlock the mysteries of space and we’ll cure disease. It was almost a token reference. Maybe less than a token reference. And then he went on to say something about national pride. As if that was the point of the science, was national pride, rather than understanding our place in the world.

And actually, I guess he was asserting our place in the world. He wasn’t asking what is it. But from the day after the election when a number of the AAAS and a number of other societies sent a letter to the President-elect, urging him to appoint quickly a well-respected person as his science adviser, it was not so that science funding would be protected particularly. It was not so that we would unlock the mysteries of space.

It was so that he would have the benefit of science in his work. And in his speech today, when he talked about the mysteries of science, there was no sense that science is an empowering agent. It gives you what you need to make good decisions and to protect yourself against deception.

IRA FLATOW: Jeff, one of the places where we still don’t have a name is NASA. Trump has not yet named a director. But he wants to unlock the mysteries of space, as we’ve talked about. Do you think–

JEFF MERVIS: That’s right. No, that’s a question mark. But historically, the NASA administrator has not been one of the early appointments. So it’s not surprising. It could be months. Even more important to the research community is who that administrator would name to run their $5 billion space mission. I mean, science directorate.

So those are positions that scientists rightly are concerned about. But you know, the short answer is stay tuned. If those are people who are respected by the community, have a track record, are familiar with the issues that Rush has been talking about, then that bodes well.

If it’s somebody who doesn’t have that background, whether they’re from industry or academia, then that’s something to be concerned about. The announcement yesterday that Francis Collins was being asked to stay on at the National Institutes of Health is not as rosy an announcement as scientists I think might have liked.

IRA FLATOW: Why is that?

JEFF MERVIS: What it actually means is that he’s being asked to stay during the transition. There’s some 50 people that the Trump transition team has deemed essential. It’s not clear what will happen. They could decide that they want to renew his term. But they don’t know.

The National Science Foundation, however, France Cordova has a six year term, which he’s only in the middle of. So you’re not hearing much angst about the National Science Foundation, which in many ways is sort of a bellwether for the government’s support for basic research. Because it funds so many different disciplines.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. We have to move on. Jeff Mervis, thank you for taking time to be with us today.

JEFF MERVIS: You’re welcome.

IRA FLATOW: Jeff Mervis, senior correspondent covering science policy at Science magazine. Rush Holt is going to stay with us. And after the break, we’re going to look at climate and environmental policy, specifically can President Trump back out of the Paris Agreement? What can we expect for the Clean Power Plan? Coming up next in our special coverage, science in the next administration. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

We’re taking a special look at how scientific research and policy could fare now that Donald Trump is officially president and under a GOP dominated Congress. Next up, what about climate change and the environment?

Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt was nominated to head the EPA. He’s been behind several lawsuits attacking the EPA’s climate regulations. Will Trump’s nominees for the Interior, for Energy, even Secretary of State help or hurt climate scientists?

My guests are Rush Holt, chief executive officer of the AAAS, a physicist, former member of Congress. Now bringing on David Gulston, government affairs director at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Welcome, David.

DAVID GULSTON: Thanks, Ira. Glad to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Within minutes of President Trump’s inaugural address, the whitehoues.gov had energy briefings up for America First policy, prioritizing harvesting our fossil fuel resources and refocusing the EPA on air and water protection, for example. Your reaction?

DAVID GULSTON: Well, it’s not a surprise. It’s in keeping with what Trump said during the campaign and the kinds of nominees he’s been appointing and some of the actions that Congress has taken in its first days of the new Congress. But it’s bad news for the environment and for health and for the American public.

It signals with even greater certainty that this administration will try to reverse Obama-era climate policy. And the one sort of positive at the end of it that they’ll supposedly refocus EPA on clean air and water, first of all, that doesn’t need to be a refocus. That’s already what the EPA does. But Scott Pruitt, the nominee for administrator of EPA, has actually made a career of attacking those EPA actions against conventional pollutants. He has not just opposed climate policy. He’s really opposed everything that’s been part of EPA’s mission.

IRA FLATOW: Rush, what are your expectations about the Paris Agreement? Do you think the President will pull out?

RUSH HOLT: Well, what I think about the Paris Agreement is you’ve got a couple hundred other countries who are already signed into it, committed to it. Of course, we should be playing a lead. We did have a leading position in the Paris negotiations.

But it’s not just about us. I do think that, judging by the President’s appointments, his statements during the campaign and since, we should expect that he’s going to at least ignore the US obligations under the Paris Agreement. And maybe seek to undo it in some sense, maybe some formal action with respect to the agreement. I would guess most likely, he’ll just ignore it.

IRA FLATOW: And I’ll ask both of you, David. There were rumors about intimidation of scientists, seeking in different levels of different research to subpoena their data.

RUSH HOLT: It certainly sent a chill through the Department of Energy, and NOAA, and other agencies when the transition team asked for information about which employees, federal employees, had taken part in climate change conferences.

There’d be no good reason to ask that question, I think, other than to give them a hard time in one way or another. Now, the administration, the incoming administration backed off on that. But it certainly sent a chill through there.

DAVID GULSTON: Yeah, and I do think we– building on what Rush said– I do think that we need to watch that. We’ll see how scientists are treated. But I think the DOE questionnaire that Rush referred to, which was withdrawn, was partly a sign of the antagonism and antipathy toward climate action by the administration, but also a sign of how thinly staffed they are. I mean, that questionnaire had pages and pages of questions, not all of them attack, that a fully staffed transition team would have had interns and low level staff working on. But they’re just not staffed that way.

IRA FLATOW: Anyway, we have a tweet from Kelly who asks, who will pick up the pieces when Trump defunds climate research?

DAVID GULSTON: So I think that it’s not clear as much what will happen with climate research. I think this is one of the things that people really need to watch. There have been rumors of everything from general cuts in research to eliminating NASA’s Earth Science program.

The thing that we know that they’ll go after is climate policy. And that’s unquestioned. And there are many tools to fight back against that, those efforts. But that’s the one thing that’s certain.

I think on climate science, it used to be that folks against climate policy used to say, oh, well let’s fund the research instead. Over the last five or ten years, that’s changed to attacking the science and the science budget, as well. But that’s sort of more up for grabs right now than the policy arena is.

IRA FLATOW: And what else do you have your eye on? Are there any bellwether issues coming up where natural resources are concerned?

DAVID GULSTON: Well, I do think the items that were outlined in the White House statement today, the Clean Power Plan, which limits carbon pollution emissions from power plants, the similar rules to limit carbon pollution from cars, which also improves auto mileage, a whole range of activities that Rush was talking about, the Paris Agreement, where there’s been the most ambivalent and ambiguous statements of sort of anything that they’ve been doing on climate.

And one area of research, which probably will be talking about later, which is research, applied research, on renewable energy and energy efficiency, that might come under direct attack from the administration. It has under some past Republican administrations.

RUSH HOLT: And of course, the irony here is that it’s been demonstrated by economists that investment in research pays off. They’ll argue about whether it pays off at 40% or 60% on investment. Whatever it is, it’s huge. And so an incoming president who’s talking about building the economy, there is an irony that there would be any discussion at all about cutting research.

But because some of this research has been viewed as political rather than scientific, it’s a political statement they’re making when they say they want to cut it. And when the head of EPA comes in, he tries to sound reasonable in his opposition to the climate policy by saying, well, there are still questions about it. Well, if there are questions about it, he should be first in line to encourage good research.

IRA FLATOW: We had a question on our Facebook page from someone from Alaska who’s worried about Arctic research. David, do you think that might be cut back?

DAVID GULSTON: Again, for all these areas of research, I think part of the threat will be efforts to shrink the federal government and federal spending overall, which tends to– research doesn’t tend to escape that. And then, the closer something is tied to climate research, I think the more of a fight there’s going to be. I think again, the policy arena is where it’s much more clear that there’s going to be a showdown.

In the case of the Arctic, one of the things that President Obama did toward the end of the administration was use authority to permanently ban drilling in most of the Arctic Ocean. We expect that to be under attack by both the Trump administration and the Congress.

IRA FLATOW: One last question before we have to go. Scott Pruitt has said he thinks states should have the freedom to set their own environmental agendas. But he did not say he would uphold California’s higher vehicle emission standards. Are we going to have a battle between states and the federal government here?

DAVID GULSTON: We may. And what you see in Scott Pruitt’s record is actually he supports states, unless they’re actually tightening environmental protections, in which case he usually is on the other side. There are a number of examples of that.

But this idea that we should leave these things to the states, we don’t have to guess what would happen. We had a long history prior to 1970 of doing that. And the results were very clear. We had pollution that could not be controlled. That’s why things moved to the federal government. That’s why we have bedrock environmental statutes.

States do not have the same kind of incentive to do this. They don’t have an incentive to prevent pollution that ends up causing problems in other states. They don’t have the wherewithal to stand up to companies that threaten to leave the state, to stop regulation.

This is an experiment we don’t need to do again. We know the results.

IRA FLATOW: I’ll move on now to another topic, and that is former Texas Governor Rick Perry is President Trump’s nominee for the Department of Energy. And when he ran for president in 2012, Perry is known for famously saying he’d abolish the Department of Energy, which he’ll be probably head of.

In his confirmation hearing yesterday, he reversed direction saying he regretted having pledged to abolish the agency and vowed to protect, quote, all the science in the department. What can we expect?

Joining us to discuss energy policy is Susan Tierney, former Assistant Secretary of Energy Policy at the Department of Energy under President Clinton. She’s a senior adviser at the Analysis Group, working on energy policy. Welcome to Science Friday.

SUSAN TIERNEY: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: So you know, it’s sort of an interesting thing with Governor Perry. He comes from a state that has one of the greenest laws about, greenest records for wind energy in the country. And yet, he’s being looked at as someone who is an oil person also. What do you think about his appointment, Susan?

SUSAN TIERNEY: Well, the first thing I thought about his appointment is that I bet he doesn’t know what the Department of Energy does. The Department of Energy is, as everyone on this conversation knows, is really a science and technology agency first and foremost. It’s an agency that’s involved in making sure that the nation’s nuclear warheads are stable, that we could use them if we ever, heaven forbid, had to.

It’s an agency that’s involved with environmental cleanup. And it’s an agency that has been pushing a variety of technologies and basic research to make sure that America really is leading on a number of different dimensions. Energy just covers the whole gamut of the economy. And I just don’t think that Governor Perry probably appreciated that.

In fact, he said that yesterday during his confirmation hearing, that he learned a lot in the last few weeks. And that he’s going to champion all of the science and all of the technology research. That’s good news.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

SUSAN TIERNEY: Ira, sorry, one of the interesting things I thought about the confirmation hearing was that across the two sides of the aisle, the senators were on the point of focusing on the science mission of the agency, and getting commitments from Governor Perry to make sure that he was going to protect scientists, protect science, protect the national laboratories and their mission. He kept saying that’s what his job will be. They can count on him. And it was clear to me that people are worried about the profile of this administration with regard to science.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. The Department of Energy houses 17 scientific labs. Are those labs likely to be eyed for budget cuts?

RUSH HOLT: Well, you know– this is rush– some of the conservative think tanks for some years have talked about privatizing the labs. It would never work. For one thing, a lot of the work with those labs is classified. You know, nuclear weapons work.

But even in the other single-purpose labs that are looking at plasma science and other such things, it’s unlikely that those could be privatized. And they certainly– the work certainly won’t go away because it needs to be done. And Governor Perry seemed to be, well, amused even at his recent discoveries. And it was good.

But on climate change, he did say he really thinks that climate change is real, and we should be doing something about it. But it shouldn’t hurt the economy. We shouldn’t let what we do hurt the economy. Well, it’s been demonstrated that bringing down carbon dioxide emissions need not hurt the economy.

IRA FLATOW: Well, there’s nothing that costs more than moving everybody away from the ocean if you don’t do anything. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, talking about the new, incoming administration and what it might mean for science.

So solar and renewables are increasingly affordable. I mean, just the other day, the price of solar power dropped so low, they didn’t want to make solar panels anymore. How much influence could energy utilities or pure economics have on the priorities of the Department of Energy?

SUSAN TIERNEY: Well, if you look at what’s happening in the markets and in states whose legislatures really love renewable energy, I think it’s going to be really hard to stem the tide of interest in pushing for a much cleaner portfolio of energy resources. You go through the different kinds of fuels that we have. And one of the promises of this administration, for example, is that they would bring back coal.

And that’s almost unimaginable how that could happen, given that this administration will also be supporting natural gas. And the low prices of natural gas are really squeezing coal out of the marketplace. So that is almost unimaginable if you look at the evidence about how you could bring back coal.

And renewable energy is the fuel of choice in so many parts of the country. And customers are stepping up and signing long term contracts. A lot of the big, high tech companies that want to control their prices as well as their carbon footprints are signing up for renewables. You look at solar panels all over the place.

So the only thing I could imagine that would be just awful would be if the Trump administration imposed import tariffs on solar panels. That would be a really bad sign. So that was one of the bellwethers that I thought of when you asked that question, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Because even the Department of Defense, you know, considers the climate as a national security issue. The Department of the Navy is incredibly green about all of the stuff that it does. And as you say, there’s a huge grassroots movement in this country to go solar and wind.

SUSAN TIERNEY: In the cities, you look around the country, cities do it to manage their own bills. They think it’s the right thing to do for their customers, their citizens, their communities. So that is where we are going. Frankly, we’re not going fast enough. And it would be very troublesome if we saw things that were stakes in the ground to really stop those trends.

IRA FLATOW: David Gulston, last comment on that?

DAVID GULSTON: Well, the other thing about it is that it’s got incredible bipartisan support, clean energy. When you do polling on environmental and energy issues, that’s the one that’s off the charts in terms of public support, even if you frame it as versus natural gas or coal. As you mentioned earlier, Texas has a big reliance on wind. Iowa has a big reliance on wind. This is an issue that’s only partisan and polarizing in Washington. And at some point when that’s the case, Washington eventually has to follow the public and the states.

IRA FLATOW: Now, the President today said he was President of the people. And if the vast majority of the people say they want to have renewable green energies, maybe he’ll listen. I want to thank all my guests who are joining us this hour. Sue Tierney, and Rush Holt’s going to stay with us. I also want to thank David Gulston, Government Affairs Director for the National Resources Defense Council, and Sue Tierney, energy economy consultant, and former Department of Energy Assistant Secretary for energy policy. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

We’re going to take a break and come back and talk lots more about the new administration and science right after this break. So stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We have been reading the tea leaves as best we can on how scientific research funding regulation could fare as the Trump administration gets up to speed and agency nominees are confirmed. We have a panel of guests, including Rush Holt, head of the AAAS. I want to ask you, Rush, before we continue with a guest, the science advisor to the president, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, has not been named yet. How important is that?

RUSH HOLT: I think it’s very important. As I said a little while ago, immediately after the election, a number of us at AAAS and other science societies urged the President to appoint a good science advisor. And I’ve tried to make the point that it’s for his sake, not for our sake, that he should have this person there.

I said, there will be crises. Probably next month. And who knows where, whether it’s an oil well blowout or an emerging disease. You don’t want to get up to speed then. You want somebody at the table with the National Security Adviser, with the domestic policy adviser, who can tell you what is known about this subject or that subject, who can bring in the expertise, who is comfortable working with other scientists. That’s really necessary.

But what is equally necessary is that we have people who are comfortable with science distributed through all of the departments. I sent a letter to every cabinet officer nominee saying, do you know that you head up a science agency?

Yes, the Attorney General. Yes, the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Yes, the Department of State. They need to have science people around them because crises and ongoing issues have science matters embedded in them.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of science matters, one area that is still somewhat murky is biomedicine. President Trump hasn’t said much about it while Health and Human Services nominee Tom Price spent more of his hearing talking about insurance. One question on researchers’ minds, though, is the fate of fetal tissue research.

Congress has had it in their sights since that Planned Parenthood video last year. And what about human embryonic stem cell research, which flourished under President Obama? Biomedical research reporter Sara Reardon has some notes on these questions. She’s been covering this beat for Nature News. She joins us from Washington. Welcome, Sara.

SARA REARDON: Hi, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: So it seems that we have very little insight into what President Trump’s administration might prioritize in biomedical research. What do you have your eye on?

SARA REARDON: Yeah, you’re right. Yeah, he really hasn’t said anything much about it at all. And we should hopefully get a little bit of clarity on that once he appoints an NIH director. He, last night, decided to keep Francis Collins on. He’s the current NIH director, but that might just be temporary. So maybe we’ll get a little better sense going ahead what the priorities of the various names that have been floated will be.

I think you mentioned embryonic stem cell research. That’s one that people have been wondering about. Right now, there are a lot of restrictions under Bush. And Obama lifted some of those restrictions with an executive order. And Trump can overturn that, essentially, with a wave of his hand. He hasn’t said anything about that.

But we know that the Vice President Mike Pence has been against embryonic stem cell research. So I think that people are a little nervous about that.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hm. The US is still daring staring down the problem of the Zika virus, which relies on our understanding of fetal development. Do you see a friendly climate for funding necessary research for combating Zika? Maybe you approach it from that direction, Sara.

SARA REARDON: Yeah, I think the thing with Zika that’s turned to political is that, to understand how it affects fetuses’ brains, you have to actually test it in fetuses and in fetal tissue, which is very widely used fetal cell lines. This is tissue that is just being discarded anyway. But Congress has launched an investigation after the Planned Parenthood videos came out last year into whether the tissue is being improperly used by scientists.

They put out a report a few weeks ago, the Special Working Group, saying that there needed to be a lot more investigation into how researchers were acquiring fetal tissue. And if that were to start being highly regulated or even banned, that would definitely make it more difficult for us to study Zika, among other things.

IRA FLATOW: Health and Human Services nominee Tom Price spent much of his hearing, as I mentioned before, discussing the Affordable Care Act. Did he say anything that might determine what research he may support?

SARA REARDON: He really said very little at all about research. He was asked about NIH. He said that he would support increasing its budget. And that seems to be the generall– the thing that’s given people a lot of hope right now is that in Congress, the general sense has been– the general feeling has been that the NIH should have an increased budget.

There may or may not be strings attached to that. But everyone, in general, loves the NIH. Yeah, he didn’t really say a whole lot about research. One of the things that– there are some ways that the Affordable Care Act is involved in research. People can use electronic health records, genomic records. Some of the programs that have been enabled under the ACA are widely used in research.

We don’t know what the future of those will be. Because we don’t know how much of it would be repealed.

IRA FLATOW: Got a tweet in from Katie who says, how screwed are all the already unemployed postdocs who don’t work in sexy fields like biomedical research like me?

SARA REARDON: I think we just don’t know again. Until we start seeing actual budgets, I think that some areas, of course, are going to be much more controversial. Climate change, if you work in renewable energy research, there might be a little more reason to be worried right now because of some of the campaign promises that he’s made.

But nobody says anything about biomedical research. Nobody has said anything about chemistry or any other field of science. So we’re kind of going to have to wait and see.

IRA FLATOW: Any ideas about, I think the President was very shocking to a lot of pharmaceutical industries when he talked about controlling prices. What about the research? Would we see any re-balancing of where the money for basic research might come from?

SARA REARDON: Some of the people who have been proposed as NIH director I’ve spoken with would like to see more partnership between NIH and private industry. And I think that that’s kind of been an area that NIH has been going anyway under Francis Collins’ leadership. They set up a Translational Medicine Institute that is specifically trying to get drugs to market. And that would also need to include industry partnerships.

A start up company by definition is able to take the kinds of big chances that NIH doesn’t tend to take. So that could be sort of a boon for them. And there’s a lot more money if you work with different industry partners. But also, the downside is it comes with a sort of conflict of interest and profit issues that we do see with some pharmaceutical research.

IRA FLATOW: One last question about research. And Rush, let me ask you this also. Given the President’s buy American and think American ideas today, what does that mean for foreign students who are here doing research as postdocs and their talents? And we going to see less of that?

RUSH HOLT: I had a call from Sweden about that just yesterday saying, everyone in our institute here has studied in the United States. What is the future of that?

And of course, no one knows. As you’ve gathered from all of today’s discussion, there’s more uncertainty than knowledge about what’s going to happen with the new administration. But one thing I would say is that for people who are concerned about education, like this anxious postdoc that just tweeted talking about the plight of postdocs and questions about funding solutions, scientists should get much more involved in policy making, in education, in public engagement, not because of Donald Trump.

But that certainly is a reminder in all of these areas. If we don’t tend to them, bad things could happen.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a great segue for you to give me. First, I want to say goodbye to Sara. Sara Reardon, thank you for taking time to be with us today.

SARA REARDON: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Sara Reardon is a biomedical policy reporter for Nature News. Speaking of getting scientists involved, we’ve been talking about science and policy and what direction it could all go. But when it comes down to it, there aren’t many scientists holding political office who are making these decisions. I think, Rush, you were the last physicist who was in office when you retired? There’s one more?

RUSH HOLT: Yes, there is. Bill Foster is a sitting member of Congress, doing a good job.

IRA FLATOW: There is a new group and PAC called 314 Action, yes, 314 as in pi, the number, who wants to change that by helping scientists with fundraising and campaigning. My next guest is the founder of that group, Shaughnessy Naughton is the founder of 314 Action, based out of Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Welcome to Science Friday.

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Hi, Ira, Rush. Thanks for having me.

RUSH HOLT: Hi, Shaughnessy.

IRA FLATOW: Shaughnessy, you have some experience working in science. But then, you ran twice for Congress. What obstacles did you run up against? And why did you want to form the 314 Action organization?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Sure. Well, one of the things that really struck me when I ran for Congress was the lack of people with scientific or technical backgrounds. And I think we see the results of that in a lot of the anti-science rhetoric we hear out of a lot of– far too many politicians.

So I founded 314 Action to try to focus the scientific community and engage the scientific community and encourage them to go beyond just the traditional advocacy and actually get involved in politics. And whether that’s running for office themselves or supporting candidates with technical backgrounds that are running for office.

IRA FLATOW: Why do you find that so few scientists are reluctant to run for office? What do they tell you?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Well, I think traditionally the mentality has been that science is above politics, as it should be. But increasingly, we see politicians meddling in science. And the structure of scientific careers aren’t as friendly as perhaps, say, a law career, or someone who owns their own business, to be able to take a step out of the lab and run for office.

But I also think it comes down to funding. And there isn’t necessarily a culture of running for office in the scientific community. And so there’s not a mentality of thinking about contributing to candidates.

IRA FLATOW: Do you sort of teach them the ABCs of how to run, to be a candidate? I’m looking at Rush Holt here, who was a candidate himself successfully. Yeah, so you teach them how to raise money and whatever?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: So, we have a candidate training coming up on Pi Day, March 14, that we’ve had already– we’ve already had 250 candidates sign up, committing to run for office. And that’s not just at the federal level. That’s all the way down to the local level.

But we’ll show them everything from how to set up a campaign, how to put together a communication strategy, what’s involved with running for office. And of course, the fundraising aspect. Because it doesn’t matter how great your message is if you don’t have the resources to communicate. It’s hard to be successful.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with Shaughnessy Naughton, founder of 314 Action.

So you’re having a teach out? Rush, is there any other advice you can give to scientists to get them to want to run, or to motivate them?

RUSH HOLT: Well, very frequently, I talk with scientists where this is at least a passing thought for them. And I tell them, yes, you can do it. It’s hard work. But there’s no real magic. Mostly, you have to get over the psychological hurdle that scientists can’t do politics, that politics is dirty, and science is pure.

You have to work on your communication skills. But mostly, you have to work on your people skills. And you can do it. Shaughnessy, you know, is someone who has run twice. It takes a lot of gumption to run again after you’ve lost once. And I really appreciate her initiative to try to encourage others now. And the training is worth doing. But it’s not mysterious.

IRA FLATOW: You had to learn how to do it. You had trouble raising money, if I remember, at the very beginning? Right?

RUSH HOLT: Well trouble, yes. But I called up everybody I knew and a lot of people I didn’t know and explained why I thought it was important and asked if they didn’t agree. And if they said yes, I said, well, can you put a check behind it?

IRA FLATOW: Shaughnessy, are you still open to getting more volunteers involved there?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Yes, yes. Like I said, we’ve had 250 candidates sign up. The process is ongoing at our website, 314action.org. And we’ve also, in the last couple of weeks, had over 1,000 people sign up to volunteer across the country. So we are always looking for more volunteers and candidates.

IRA FLATOW: And as you pointed out in your literature, there are 300,000 elected officials– we’re not just talking about senators, state– there are local school boards, all kinds of ways to get involved, working your way up, right?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Correct, correct. And frankly, we are going to have much more success at the federal level if we get more people elected to school boards, and county commissions, as well as the state legislatures.

RUSH HOLT: Ira, just as I was making the point that every cabinet office has science in it, it is a science agency, so every decision making position in this country and others has science there. And there should be people who are at least comfortable with science, if not actual trained scientists, available on the city council, in the school boards throughout. And it’s not only a matter of giving back. It can be really exciting to be part of progress.

IRA FLATOW: And Shaughnessy, from your own experience, I guess you have to learn how to grow another layer of skin?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Yes, you do. But I think the only way we’re going to see a more pro-science agenda is to get more people with scientific training and technical backgrounds to run and be successful. And that’s what we are working to do.

IRA FLATOW: All right. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. Rush Holt, chief executive officer of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, better known as the AAAS.

RUSH HOLT: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Former Democratic Congressman from New Jersey. And Shaughnessy Naughton, founder of 314 Action, based out of Bucks County. The website, 314action.org. Shaughnessy?

SHAUGHNESSY NAUGHTON: Yes, thank you, Ira. Thanks, Rush.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you both for taking the time to be with us today.

Charles Bergquist is our director. Our senior producer, Christopher Intagliata. Our producers are Alexa Lim, Annie Minoff, Christie Taylor, and Katie Hiler. Luke Groskin is our video producer. Rich Kim, our technical director. Sarah Fishman, Jacques Horowitz are our engineers. At the controls here at the studios of our production partners, the City University of New York.

If you were having trouble hearing us today, we’re on our website at sciencefriday.com. You can listen to the stream a little bit later and the podcast. So you can catch up in case you missed it today. Have a great weekend. I’m Ira Flatow in New York.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.