Soft Robot Gives Jellyfish A Hug

10:56 minutes

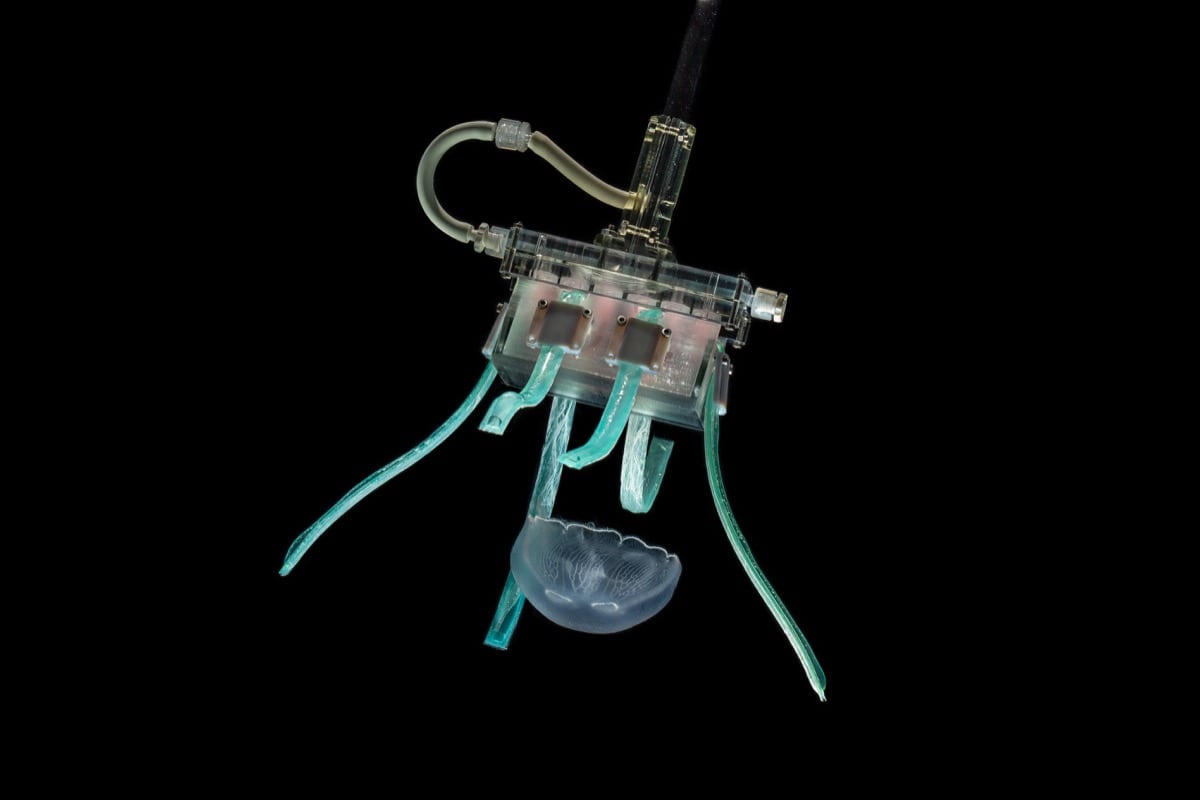

One of the biggest problems in marine biology is a practical one. How do you study ocean life? Some of the ocean’s most delicate creatures—brittle coral, miniature squid, and squishy jellyfish —can’t make the journey to the lab for further study. So, marine scientists are looking to bring the lab to them, with a new suite of soft robotics that can safely perform tests on these organisms while still underwater. And this week in the journal Science Robotics, scientists report making progress towards that goal, with a six-fingered robotic gripper. The soft robotic hand can capture something as delicate as a jellyfish, which is 95% water, without harming it.

David Gruber, the presidential professor of biology at Baruch College at the City University of New York and a National Geographic Explorer, joins Ira to talk about how the new jellyfish gripper and other soft robots are helping marine biologists more carefully study ocean life.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

David Gruber is a professor of biology at Baruch College at City University of New York.

IRA FLATOW: One of the biggest problems in marine biology? It’s a very basic one. How do you study ocean life?

Well, some of the ocean’s most delicate creatures– you have brittle coral, miniature squid, squishy jellyfish. They can’t survive the journey to the lab for further study. So marine scientists are looking to bring the lab to them.

And this week, scientists report making progress towards that goal with a six-fingered robotic gripper. You got to see this thing. The soft robotic hand can gently catch and release something as delicate as a jellyfish, which is 95% water, do this without harming it. Here to tell us how these jellyfish gripper and other soft robotics are making it possible to build a future underwater lab is David Gruber, a professor of biology at Baruch College at the City University of New York. Dr. Gruber, welcome to Science Friday.

DAVID GRUBER: Thanks so much, Ira. Pleasure to be here.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. So you’re a marine biologist. Why is it so difficult to study things like jellyfish?

DAVID GRUBER: I think you know, we do our work sometimes a kilometer under the ocean. So when we’re working down there it’s really hard to just stick our hand out of the submarine and set up a lab bench. So we’ve been working over the last several years of designing something with the dexterity of a human hand that we could use underwater.

IRA FLATOW: And I watched the video of how this was working, and it’s sort of like long fingers. You describe it to us how it works.

DAVID GRUBER: Well, these specific soft robotics, they’re ultra-gentle, and they’re known– we call them lovingly in the lab as fettuccine fingers because they look almost like a piece of fettuccine. But when you could touch something with it, they are 1/10 of the pressure of the human eyelid resting on the eyeball. So they’re just incredibly gentle.

IRA FLATOW: Right, So This allows you to, then, sort of gently hold the jellyfish underwater so you don’t have to take it out. And then you can study them that way?

DAVID GRUBER: Yeah, that’s exactly correct, and this is part of a longstanding collaboration with the Harvard micro robotics lab. And I [? have been ?] showing a video at National Geographic using this hard metal claw, and I was having a hard time working with a sample.

And Rob Wood, who heads that lab, kind of came up to me afterwards and started peppering me with questions about what I’d use to interact with animals. And he ended it with, have you heard of soft robotics? And the answer was no.

IRA FLATOW: Why can’t you just put a jar in there? Like–

DAVID GRUBER: Yeah, I mean, you could.

IRA FLATOW: Why could you– well, OK, so what’s the drawback to that?

DAVID GRUBER: Well, I mean, you could put a jar in there. There’s something known as a desampler. Essentially, the jellyfish would just fall into the jar, and then a lid would come over and close up on the jellyfish.

But in that scenario, we would still have to bring the animal to the surface to do any further work. And I think as a marine biologist, I got into marine biology due to a really deep love for marine animals and empathy in working with them. And something about bringing these animals from the deep sea where they’re incredibly beautiful and have this form and then seeing them as this blob on the surface dead is really not satisfying.

So this is a way to be able to interact and work with animals in their own setting. And essentially, we like to not kill them. It’s a little bit like giving them a doctor’s checkup where we would come in, and we could swab them and take their DNA and take physiological measurements. We could even 3D scan them and print out an exact replica of the surface and essentially then open it up and let this jellyfish swim away.

IRA FLATOW: It’s really amazing. Have you gotten to test this new jellyfish gripper out there in real life yet?

DAVID GRUBER: Well, we’ve– I feel a little bit like Q in James Bond working with the Harvard micro robotics lab where I tell them a scenario. And I particularly chose jellyfish just because they’re so difficult. And when working with this lab, I like to give them just incredible challenges.

So this animal that almost falls apart in the hand, asking them, can you develop me a soft robot, an ultra gentle robot, that can help me study this animal and not hurt it? And we started out at the New England Aquarium. And we did our first test there. But there’s a whole suite of delicate, soft robotic devices that are coming out of the micro robotics lab that are allowing us to better understand deep sea life.

IRA FLATOW: And let’s talk about– this isn’t the first robot you’ve worked on, right? There’s another underwater gripper that also catches delicate sea creatures. How does that one work?

DAVID GRUBER: Yeah, well, one of them– we try to come up with nice names for them. So the first one was just called squishy robot fingers. And then the next one that you’re mentioning was something called a rotary actuated dodecahedron, which is kind of a mouthful.

And what that is, it’s essentially something like– its origami-inspired. So it starts out as a flat sheet. And with one rotation, it turns into a sphere. And in this scenario, we would approach a jellyfish, and we would enclose the jellyfish inside this RAD device as a way to keep it in place. And then once we have it in place now, the goal is to use these fettuccine ultra-gentle fingers to go around it and to swap the jellyfish and to do any other physiological measurements [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: Would you be using these tools during the same dive?

DAVID GRUBER: Yeah, the idea is essentially to– one of the real goals is just to not stress out the animal and to not hurt it. And we try to use tandem as many things as we can on the same dive. So it’s like– it’s been a real stepwise process.

Even on the first dive when I was working with this laboratory, we didn’t know if the squishy robot fingers would just implode at depth. So the first one, we actually just brought one of these down with us and just took a camera just to visualize what happened. And it was fine.

IRA FLATOW: And you have enough funding for this? People can support it, make it practical?

DAVID GRUBER: Yeah, this started out in as a National Geographic innovation challenge grant. So it started out as a really small grant. We now have an NSF grant where next year, we’ll be going to sea and testing this out with the Schmidt Oceanographic Institute.

So it’s doing OK. And what we really love is that how it’s catching on, that marine biologists really– we were using tools from the oil and gas and the military to do heavy construction under water. And there’s not been a real big effort to design incredibly delicate tools for us. So we’re slowly seeing this being adopted by other members of the marine biological community.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday in WNYC Studios. I’m talking with David Gruber, professor of biology at Baruch College at City University of New York about his way of gently catching jellyfish.

I’m glad you’re getting funding because I don’t want to see you on “Shark Tank” trying to get those sharks to protect your jellyfish. So– see what I did there? Sorry. What are you most interested, Dr. Gruber, in learning from jellyfish?

DAVID GRUBER: I mean, jellyfish are interesting to me just because they’re this animal that everybody’s experienced. Everybody’s seen a jellyfish. But we all have different impressions.

Some people, it reminds them of being stung at the beach, and it’s ruined their vacation. Other people have it as their screen savers. So they’re these really kind of mysterious alien life forms.

But they do have superpowers. There’s a molecule called green fluorescent protein that was discovered from a jellyfish in the ’60s, which led to a Nobel Prize in 2008. And that’s really revolutionized experimental biology, how we see the inside of cells, how we see gene expression.

There’s another thing about jellyfish now is that I’m thinking about the oldest animals on our planet. And jellyfish have a trait. And you may have heard of the immortal jellyfish where once they’re an adult, they can actually have the capability of reverting back into youth. So these animals that are kind of right under our nose just have some of these just credibly remarkable features that we can learn more about.

IRA FLATOW: Is it just the features, or could it be some of the biochemicals they have in their bodies that might be of interest to us?

DAVID GRUBER: Everything, and it’s really about– I think one of the real premise of this work is about how we approach life. And even something as backwater as a jellyfish is something that we should, when we approach and we encounter this animal, that we should value it and try not to kill it as we study it.

IRA FLATOW: It has been around a long time. So–

DAVID GRUBER: Yep, 500 million years. So that’s the other thing. I think of the state of where humans are and how we’re kind of bringing on our own extinction event. And here is this mysterious, drifting animal out there that has so much to teach us.

IRA FLATOW: So you think they’re going to outlast the human race is what you’re saying.

DAVID GRUBER: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: You must be working on the next product, you know? You must be working on an improvement, I’ll bet.

DAVID GRUBER: There’s always– you know, I think that’s with working. So I did this fellowship at Harvard, Radcliffe Fellow, where I got to spend a year as a biologist to be a fly on the wall in this robotic lab. And it’s just completely impressive in how they work and the dedication. And it’s build and rebuild and build. And even with this ultra-gentle fettuccine finger, we went through several iterations of fail until we were able to grasp the jellyfish correctly.

IRA FLATOW: Well, as most people in science know, failure is an option. Thank you, David Gruber–

DAVID GRUBER: My pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: –taking time to be with us today. Good luck on your next project and on this one.

DAVID GRUBER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: David Gruber, professor of biology at Baruch college at the City University of New York.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.