Your Smart TV Is Watching You

17:24 minutes

Today, it’s much easier to find smart TVs on the market. Companies like Vizio and Samsung create devices capable of internet connection and with built-in apps that let you quickly access your favorite streaming services. But that convenience comes with a hidden cost—one you pay for with your data.

Smart TVs have joined the list of internet connected devices looking to harvest your data. They can track what shows you watch, then use that data to deliver targeted ads, just like Facebook. Not worried about what media companies know about your binge watching habits? New research suggests that’s not everything smart TVs are doing. If you are the owner of just one of many “internet of things” devices in your home, those devices could be talking to each other, influencing what gets advertised to you on your phone, tablet, and TV screen.

Dave Choffnes, associate professor of computer science at Northeastern University, and Nick Feamster, director of the Center for Data and Computing at the University of Chicago, join Ira to share what they each found when they looked into the spying habits of your smart devices. Plus, want to know where the data your smart TV collects is going? Princeton University researchers created a tool to track that information (Ira gave the “IoT” inspector a spin at his own home). And here’s a detailed model-by-mobel guide to turning off the snooping features on your smart TV (without breaking anything).

These comments from the interview have been edited lightly for length and clarity. You can find the full segment transcript below.

Which smart devices are collecting information on you?

Dave Choffnes: For the most part, anything that’s connected to the internet can be collecting data. We see even by just turning on devices, not even interacting with them at all, they’re communicating with other destinations. They’re collecting data.

What data is your smart TV collecting?

Dave Choffnes: It really depends on the smart TV, and of course it goes beyond smart TVs. But ultimately, what we know is that as we increasingly have internet connected devices in our homes, they’re communicating with other companies over the internet. Often they’re communicating with servers run by Amazon, Google, a number of other companies, and communicating with known advertisers and analytics companies who, at least on mobile apps and websites, are collecting data about individuals for tracking and profiling.

Nick Feamster: It’s a variety of things. I think one of the things that we found surprising was that some of the channels that we looked at, we found them sending quite detailed information, including the video title. So exactly the title of the show or the video that you were watching. Of the 2,000 channels that we looked at on Roku and Amazon, many of them sent back unique identifiers, something called an ad ID. And many of them also sent back other more detailed information, including the serial number of the device, as well as, your city, state, and zip code in some cases.

What are third parties doing with the data?

Nick Feamster: We don’t know everything that they’re doing with it, and I think that’s probably something that certainly we should be more concerned about. But one thing that we definitely know that they’re doing with it is advertising to us. Basically, sending us targeted ads. Many of the most prevalent trackers—generally, the organizations that collect data about us—those are advertising companies. Many of the most prominent trackers are actually Google and Facebook.

What does this mean for the “internet of things” in your home?

Dave Choffnes: It’s not just the TVs watching what we’re watching. We have devices that have cameras on them, devices with microphones, motion sensors. So essentially, the space that we traditionally considered private, the space between the walls of our home, are now increasingly occupied by devices that are watching us from the inside.

We saw examples of cases where the smart speakers are listening when they shouldn’t be—when the wake words are not triggered. We see cases where video cameras are taking footage or images and sending them over the internet, sometimes not even securely. And all of this is happening usually without users being aware.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dave Choffnes is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at Northeastern University.

Nick Feamster is a professor of Computer Science and the director for the Center for Data and Computing at the University of Chicago.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. How many of you have a smart TV at home?

Raise your hand. No, no– you can put it down now. You know, the brands like Visio and Samsung that come with an internet connection. They have those built-in apps at the bottom of the screen that let you quickly load your favorite streaming services.

Well they are the future. They are affordable and convenient. But they also come with a hidden cost, when you pay with your data. By that, I mean, that the smart TV and streaming devices have joined ranks with websites and cell phone apps in harvesting and sharing your information.

They track what shows you watch. And then they share that data with third parties to deliver targeted ads, just like notorious privacy rights bogeymen, Facebook. Yes, so this week we asked our listeners, how concerned are you about your internet connected devices snooping on you? And a lot of you sent in your answers via the Science Friday VoxPop app. And here’s a sample of what you had to say.

JEFF: I have smart speakers from both Google and Amazon all over the house. And I’m not the least bit worried.

LAURA: So I do have a smart speaker. And lately, I’ve been kind of suspicious of it. I usually thought that was kind of funny when people thought they were being listened to. But lately, without me speaking, I can’t see the light turning on without me saying her name first. And then just will automatically turn off. But it seems like it’s listening and somehow.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Thanks to Jeff from Kingston, Laura from Maryland for sharing their thoughts with us. And if you’d like to share your thoughts with us right now, give us a call. Our number 844-724-8255– 844-724-8255. Or you can tweet us @SciFri.

What do you think about– how concerned are you about your internet connected device snooping on you. But maybe you’re not worried about what media companies know about your binge watching habits. New research suggests that not all smart TV are tracking.

Here with me to talk about two new studies looking at TV tracking are my guests. Let me introduce them to you, Dave Choffnes, Associate Professor of Computer Science at Northeastern University. And Nick Feamster, Professor of Computer Science and Director for the Center for Data and Computing at the University of Chicago. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAVE CHOFFNES: Thanks for having me.

NICK FEAMSTER: Thanks great to talk to you.

Nice, thank you, you’re welcome. David, most people are aware that websites and cell phone apps are collecting your data. What data is your smart TV collecting?

DAVE CHOFFNES: Well it really depends on the smart TV. And of course, it goes beyond smart TV’s. But ultimately, what we know is as we increasingly have internet connected devices in our homes, they’re communicating with other companies over the internet.

Often communicating with servers run by Amazon, Google– a number of other companies, and communicating with known advertisers and analytics companies who at least, on mobile apps and on websites are collecting data about individuals for tracking and profiling.

IRA FLATOW: Now, let’s say you don’t have a smart TV. But I have an Apple TV or Roku or a stick, you know, an Amazon stick connected. Are they also collecting data?

DAVE CHOFFNES: For the most part, anything that’s connected to the internet can be collecting data. And we see even by just turning on devices, not even interacting with them at all, they’re communicating with other destinations. They’re collecting data.

IRA FLATOW: Nick, in a recent study you looked at how the apps on your smart TV’s are sending information to third parties. Give me an idea, what kind of data they’re collecting? Is it what channel you’re watching, what commercials you’re watching, what kind of stuff do they want to know?

NICK FEAMSTER: It’s a variety of things, Ira. And I think one of the things that we found surprising was that some of the channels that we looked at, we found them sending quite detailed information, including the video title. So exactly the title of the show or the video that you were watching.

Of the 2000 channels that we looked at on Roku and Amazon, many of them sent back unique identifiers, something called an ad ID. And many of them also sent back other more detailed information, including the serial number of the device. As well as, your city, state, and zip code in some cases.

IRA FLATOW: And so, what are the third parties doing with this when they get that information?

NICK FEAMSTER: We don’t know everything that they’re doing with it. And I think that’s probably something that you know, certainly we should be more concerned about. But one thing that we definitely know that they’re doing with it is advertising to us. Basically, sending us targeted ads.

Many of the most prevalent trackers, generally, the organizations that collect data about us, we refer to them as trackers. And generally, those are advertising companies. Many the most prominent trackers are actually Google and Facebook.

IRA FLATOW: David, your paper looked at what the TV itself was tracking when you turned it on. Tell us what you found.

DAVE CHOFFNES: Well, one of the big challenges we have in this field is for a lot of these devices in your home, we can’t actually see what is the data that they’re collecting. For instance, we can’t even see that there’s an ad ID like Nick just mentioned. But we can see who they’re communicating with.

So for example, what we found is on TVs, like the LG TV or Samsung TV, if you open an app, like Netflix, for example, it’ll communicate with Netflix as you’d expect. But even if you don’t sign in and you don’t have an account. Now if you turn off your TV and turn it back on, that app automatically starts again and will communicate with Netflix, again.

And so, you know, what we see is that the apps are essentially sending information about individuals. Those other destinations can learn your IP address. From that they can figure out where you’re located. And they know what kind of TV you have. And combine that with a bunch of other information that they track from other sources like your mobile device, they can start building a profile of where you are, when you’re home, and eventually, even what you’re watching.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the other devices because you also discovered that our smart TV’s might be talking with other smart devices in our home, right?

DAVE CHOFFNES: Yes, so the thing that we’re concerned about is increasingly, it’s not just the TVs and that they’re watching what we’re watching but we have devices that have cameras on them. Devices with microphones, motion sensors– so essentially, the space that we traditionally considered private, the space between the walls of our home, are now increasingly occupied by devices that are watching us from the inside. So we saw examples of cases as one of your listeners pointed out, where the smart speakers are listening when they shouldn’t be. When the wake words are not triggered. We see cases where video cameras are taking footage or images and sending them over the internet, sometimes not even securely. And all of this is happening usually without users being aware.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re on all the time. And even when we don’t say the magic name that we evoke them.

DAVE CHOFFNES: Right, so exactly. We actually did a small study and we’re expanding it, but we started by just trying to play a lot of dialogue. Things that people say to each other at these devices. So we started with a Gilmore Girls episode because they say a lot of words per minute. So we’d have a lot of data to throw at it. And we saw some activations that were, kind of, they made sense some things sounded like Alexa. But we also saw things that, you know, weren’t terribly expected. Like, I need medical assistance woke up the device that was listening for Alexa and we think it’s somewhere between medical and assistance that kind of sounds like Alexa. But it does kind of get you thinking, what other kinds of things might they be listening for or accidentally wake up to.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones, because lots of people want to talk about this. Let’s go to Houston with David. Hi, welcome to Science Friday. Go ahead David.

DAVID: Hi, are you there?

IRA FLATOW: Yes, go ahead.

DAVID: Hi. Well, so I’ve been listening. And I like you guys. I listen all the time.

I work at NASA. And for the smart TV thing, personally, I just don’t even enable them to the network. I just leave them off the network and make them dumb TV’s. And part of that is what we did about three years ago, when these things started coming out.

We were concerned about the traffic that was coming out of these devices. And who they were talking to, so we set up a lab and instrumented and all these devices. And started kind of tracking what they were doing.

And what we found was a lot of the traffic is encrypted. And so you don’t really know what they’re saying. And we also found that they need to communicate back to their mothership in order to do the updates and take care of themselves. And so you had to have the connection open but kind of the solution that we’ll just put them on a network that’s not on the same network that your data is. That’s kind of where we got too.

IRA FLATOW: You walled them off. Is that one answer, David and Nick?

NICK FEAMSTER: Yes, I think a couple of things, you know, he’s right on the money that. In many cases, a lot of the traffic– and David mentioned this as well. A lot of the traffic that we’d like to know more about that’s leaving our houses is encrypted. So it can be tough to learn about it. In our study, we managed to actually break the encryption for two of these devices, the Roku and the Amazon Fire TV.

So we were able to get a little bit more information about the types of things that the devices were sending back. But in general, that’s a tricky problem.

DAVE CHOFFNES: And it’s true that one way you can approach this problem is saying you know, I’m just going to make everything dumb by not giving it an internet connection. That may be fine for some devices but for other devices, it just may not work. If you don’t give it any internet connectivity. And so now, you’re left with this question, know what connections do I allow? Which ones are actually necessary for the device to work versus which ones could you block and maybe avoid some of the risk of information exposure?

NICK FEAMSTER: There’s an additional consideration there to Ira, which is that many households and many spaces are multi-user. Right? So you might make one decision but your wife or your kids might have different ideas about what’s OK. What kind of data is all right and what should or shouldn’t be connected to the network. So these starts of situations get particularly complicated when we have situations with multiple users or people who don’t have the autonomy to make choices.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Laura in Huntington, Long Island. Hi Laura.

LAURA: Hi, how are you?

IRA FLATOW: Hi there, go ahead.

LAURA: OK, so what happened is– there’s a game and I’m forgetting the name of it– the kids play on Alexa. Where it’s basically, Alexa saying, I can guess anyone in the world that you’re thinking about. And it’s usually like, is this person a Disney Princess? Or whatever– they narrow it down. And then Alexa will say, are you thinking about Elsa? And my daughter laughs and says yes.

But they also do it with like, real people, right? So the kids always pick out babysitters or family members. And one day my daughter was playing and she thought of her dad. So through the questions, we got down to where Alexis said, does this male live in your house? And my daughter said yes. And then Alexis said, was this male in love with your mother? And she laughed and said yes. And then it says, does this male inoculate all the children in his house?

And I look at her, my daughter knows vaccinate, doesn’t know inoculate. And I put my finger up like, don’t answer that. We were do inoculate but I don’t want– I don’t– you know, that’s ridiculous. So Alexa repeated the question, and again said, does this man inoculate the children in his house, all the children in his house? And I just said, Alexa mind your own business. And Alexa said, you know, OK. I think you’re thinking of your father, is that right? My daughter laughs and says yes.

But it was pretty horrifying like, OK one thing for marketing to collect information, like does your dad need a new car? But you know, obviously, inoculation is such a hot topic right now, particularly in New York where there’s a lot of students who didn’t get return to school this fall–

IRA FLATOW: OK, Laura, we’re running out of time. [INAUDIBLE] it’s a great, great anecdote– what do you think of that?

NICK FEAMSTER: Related to Laura’s observation and related to our study of third parties collecting data, we actually just completed a study of Alexa apps, they’re called skills. And one of the shocking things Laura, is that not only was the Alexa trying to collect that information about you. But you may not even know who or what organization was doing that. Because when you ask a question of Alexa, sometimes it’ll install software from third parties to help get answers to those questions.

Often without asking you. So not only is somebody asking you about inoculation practices in your house. But you probably don’t even have any idea who that is. It’s probably not Amazon.

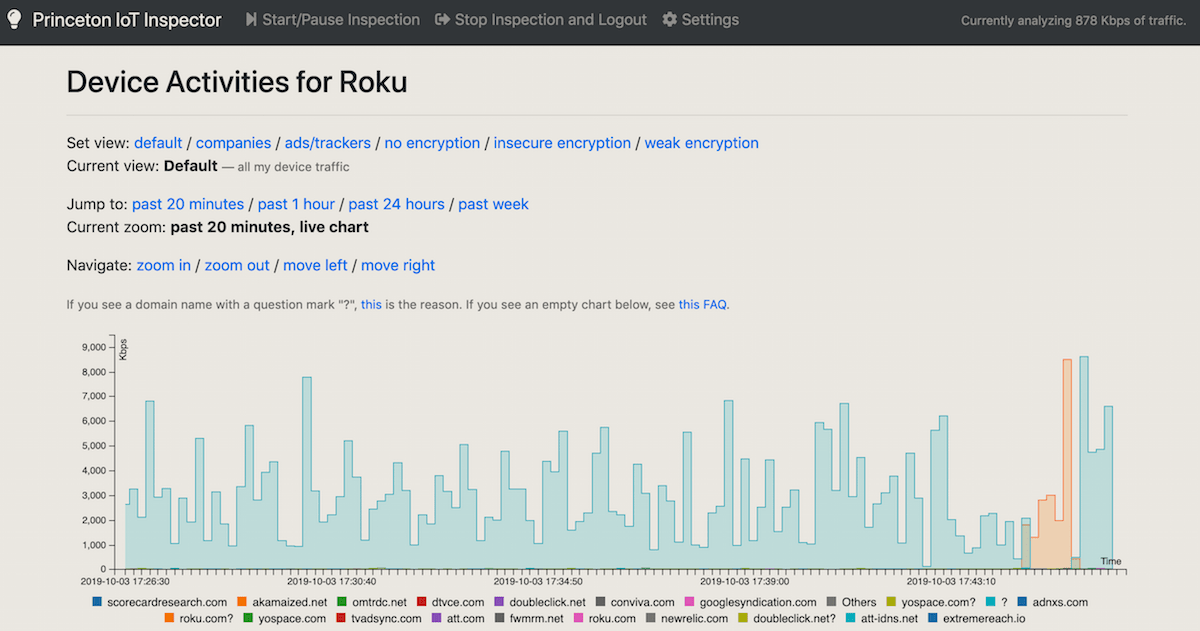

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Talking about your internet of things– in the few minutes we have, I wanted to talk to you Nick, about a project out of Princeton called the internet of things inspector. It’s a piece of software that I actually installed last night to watch it. It pings to all your devices in your home. It keeps track of what they’re sending. And I used it on my Roku and I– on the website at Science Friday, [INAUDIBLE] you can see a 20 minute little piece of video I put up there that shows 20 minutes of usage. And how many things my Roku was talking to in just those 20 minutes was amazing.

NICK FEAMSTER: Yes, you can see, Ira, this is not just a academic paperware. Right? It’s real problems in your homes, as well. And the credit for this tool, I should mention, goes to a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton, Danny Huang. And we got together and we basically realized that people are buying all kinds of things.

And they just have no idea when they plug it into the internet what’s going on. What is this device talking to? And you know, it’s one thing to write a paper but you know, we really want to provide users consumers with better information. So that when they buy something off the internet or off of the shelves at the store, they know what they’re getting into and what they’re letting into their home.

And the idea was like, can we make this as close as possible to a one click, give the user the best information they can, and the easiest way possible. And I’m excited that you were able to get the information. And I hope many of your listeners will try it out to.

IRA FLATOW: Well, it’s great. It’s called the internet of things inspector and you can just Google it and find it. Google it. Really is shocking how many– there’s a graph of my Roku up there about how many different places it was going to. David, is there any way to keep your smart home disconnected and still have your devices working?

DAVE CHOFFNES: So this is actually a project that we’re actively working on. So what we do is we interact in an automated way with devices. And then, just block one, then the next connection, and so on. Keep blocking connections and see if the device still works. So at the end of this study we’ll be able to produce something where you could say install a device in your home that just blocks everything that’s unnecessary for a device. And only keep the connections you actually need.

IRA FLATOW: I started looking at a hub called Hubitat. Which supposedly, will keep things in your home connected to each other but does not go out to the internet. And I’m looking into that. It’s pretty interesting. Are you familiar with that?

DAVE CHOFFNES: Not precisely, but it really depends on what kind of device you’re using. For instance, some devices you cannot interact with them, unless it has an internet connection, so– And this is actually one of the counterintuitive things for a lot of people is you’re in your home with your smartphone trying to turn on your lights or whatever operation you’re doing and you think, you’d make that operation and all that network traffic, all the commands stay in your home.

When in many cases, it actually leaves your home, goes off to some server in the cloud, and then comes back from the cloud to talk to your device. So that’s another example this counterintuitive behavior that you could see, for example, from IoT inspector, that you know, invisibly– there’s a lot going on in your home that you may not expect.

NICK FEAMSTER: Yes, Ira, another one that I would add is that this study on smart TV’s had an interesting result where you could turn on tracking protection on the Roku. And it basically, barely did anything as far as blocking the trackers that the device communicated with. There’s some other interesting technology in this area.

One of them is called Winston Privacy, if you’ve read, 1984, you’ll get the reference. These guys are basically trying to build a firewall you could drop into your home, put it basically in between your home router and the access point and do exactly what David is talking about.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Nick we’ll check back with you and David. And Nick Feamster and David Choffnes, working on keeping you isolated from bad things on the internet. Thank you for both for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.