Algae, The Mighty Slime Of The Planet

16:27 minutes

When you think of algae, one of the first images that might come to mind is the green, fluffy stuff that takes over your fish tank when it needs cleaning, or maybe the ropy seaweed that washes up on the beach. But the diversity of the group of photosynthetic organisms is vast—ranging from small cyanobacteria to lichens to multicellular mats of seaweed. Author Ruth Kassinger calls algae “the most powerful organisms on the planet.” She talks about how this ancient group of organisms produces at least 50% of the oxygen on Earth, and how people are trying to harness algae as a food source, alternative fuel, and even a way to make cows burp less methane.

Try out a seaweed-inspired recipe from Kassinger’s book below, and read a excerpt from the book about how nori is produced on seaweed farms in South Korea.

Dulse (Palmaria) is a beautiful dark rose- to burgundy-colored seaweed that grows abundantly on the northern coasts of the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Its fronds are about 18 inches long and a just few inches wide.

In the year 600, the monks of St. Columba, in Scotland, noted that people ate dulse, and no doubt it had been on the menu for a long time. In an article titled “Purple Shore” in Household Words, a magazine edited by Charles Dickens, an anonymous author wrote in 1856 that the fishermen in the region pressed dulse “between two red-hot irons, which makes it taste like roasted oysters.” Recalling childhood holidays in Aberdeen, the author remembers how, often, more than a dozen “dulse-wives” would be selling the seaweed:

Of all the figures on the Castlegate, none were more picturesque than the dulse-wives. They sat in a row on little wooden stools, with their wicker creels placed before them on the granite paving stones. Dressed in clean white mutches, or caps, with silk-handkerchiefs spread over their breasts, and blue stuff wrappers and petticoats, the ruddy and sonsie [healthy] dulse women looked the types of health and strength… Many a time, where my whole weekly income was a halfpenny, a Friday’s bawbee [silver coin], I have expended it on dulse, in preference to apples, pears, blackberries, cranberries, strawberries, wild peas and sugarsticks.

Dulse was generally eaten raw, the author reports, or used to season oat or wheat bread.

I ordered dried dulse from Maine Coast Sea Vegetables, both regular and applewood-smoked. I rehydrated it and nibbled it uncooked to see if I would have spent my halfpenny on dulse or blackberries. While I’d have bought the blackberries, I found the smoked dulse intriguing. It has a strong Scotch whisky flavor, and would be a treat on a tray of hors d’oeuvres along with cured Greek olives, sharp cheese, and other savory nibbles. And, dulse is a wonderful addition to cheese scones.

Chef’s tip: Dulse flakes are dried and quite stiff. If they are added as an ingredient in baked goods, it is a good idea to first rinse the flakes quickly in a sieve under tepid water to give them a bit of moisture.

The following recipe is from Slime: How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us by Ruth Kassinger. Copyright © 2019 by Ruth Kassinger. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Ruth Kassinger is a science writer and author of Slime: How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019). She’s based in Bethesda, Maryland.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. As a kid, the first time I saw a polar bear at the zoo, I was shocked to see that its fur was green. Where did that green come from, I wondered. Well, years later, I would learn that polar bear fur was actually hollow. And in the hollows would grow algae, finding its way in from the water polar bears like to swim in. Those bears started me on a lifelong citizen science quest about algae.

Do you ever think about algae? If you have a fish tank, you do, seeing it growing on the glass in bright green floppy mats. Boy, I encountered that in my fish tank. Fact is that algae is all around us, for good and bad. Algae provide 50% of the oxygen that we breathe, but they can also bloom into poisonous and deadly pools. These ancient organisms are a big part of photosynthesis on our planet. But they usually go unnoticed until something bad happens.

My next guest says you won’t find algae dressed in flowers, wafting scents or sporting seeds and berries. Plants are the fancy-pants photosynthesizers of our world. Algae are the plain janes. And in fact, she says, algae are not plants. We’ll talk about that. And in her new book, she gives these plain janes their time in the sun, sharing with us her hunt to see how algae are used around the world for food, alternative fuels, and importantly, for a healthy planet.

Ruth Kassinger is a science writer based out of Bethesda. And her new book is called Slime, How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us. Welcome to Science Friday.

RUTH KASSINGER: Thank you for inviting me. I’m delighted to be here.

IRA FLATOW: I love how that name rolls off your tongue when you– took some while for you to do that, I’m sure. We have an excerpt of your book on our website. It’s sciencefriday.com/slime. Ruth, you might get this a lot. But how did you get interested in algae? I mean, I got interested, and I told you about the zoo. It became a lifelong passion for me. How did it happen for you?

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, I was working on another book, a book about the history of conservatories, glass conservatories, and looking for the most modern representation of one of those. And that took me to El Paso, Texas in about 2008, where an entrepreneur was growing algae underneath a glass conservatory and growing it in clear plastic panels that were about 8 feet tall and 4 feet wide and a few inches thick, and filled with water that had algae growing in it.

And he was determined to grow the algae, spin the water out of the algae, and then get the oil out of the algae. And he was doing it. His business didn’t survive. But I was so fascinated by this because wow, here we are making oil, instead of taking it out of the ground. And we’re doing it without using any arable land or any fresh water. It just seemed great to me. And the more I looked into algae, the more I realized that even this wonderful application was just a small part of what algae is all about.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about that, what algae actually is. Because I think people are shocked to learn that algae is not a plant, is it? What exactly is it?

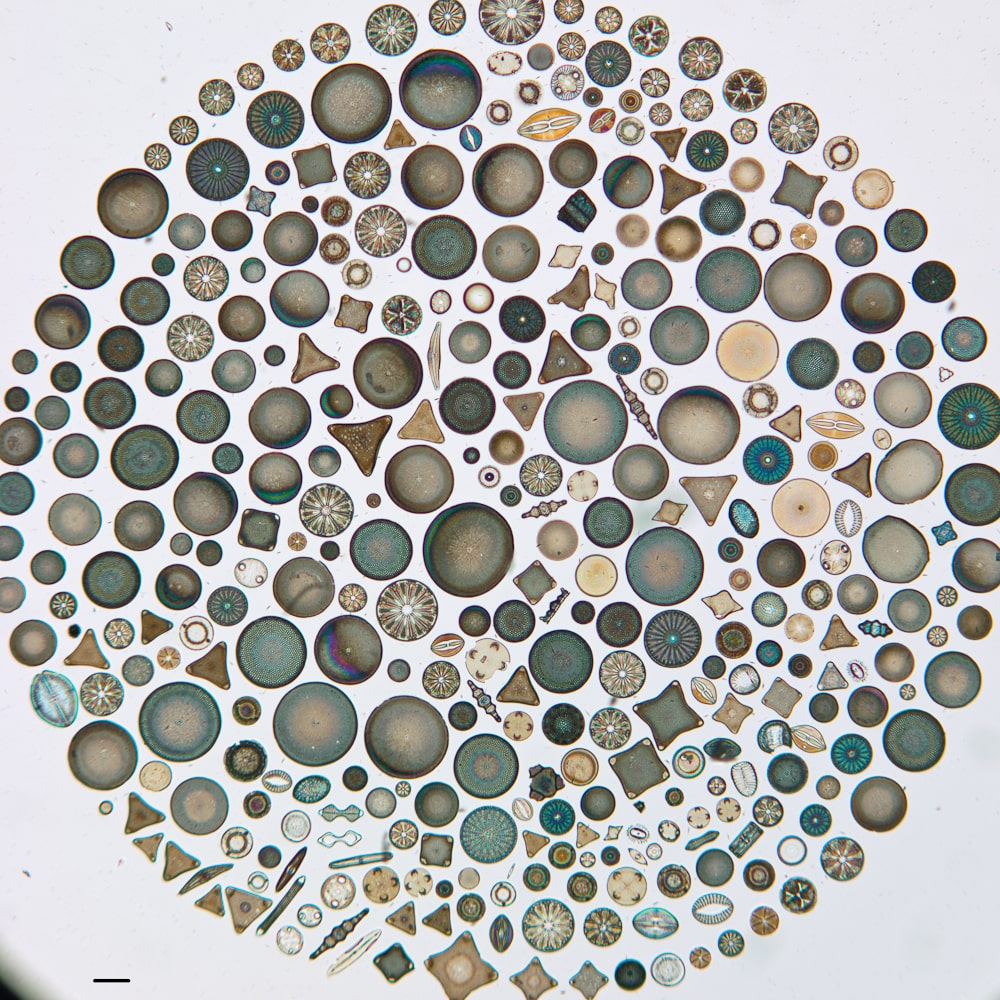

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, you know, it’s really hard to say exactly what algae is. Because it’s not a taxonomic category, like Animalia or Homo sapiens. It’s actually a catch-all term that refers to three different kinds of organisms. The smallest one is cyanobacteria, and that is a very simple organism related to bacteria, only it photosynthesizes.

Then there are microalgae, which are a little bit larger, but still invisible. And they’re more complicated inside and can produce a lot more kinds of proteins, and vitamins, and things that we really appreciate. And then there are macroalgae, which are the seaweeds. Those are the conglomerations of algae that actually have parts like a plant.

But as you said in your opening, algae are definitely not part of the plant community. They don’t have bark. They don’t have stems. They don’t have flowers. So they actually are more efficient at taking sunlight and turning it into things that we like, rather than turning it into plant material.

IRA FLATOW: In my quest to study algae over the years, I’ve learned some interesting facts that I’d like to check with you. For example, 90% of all the green stuff growing in the ocean are not plants. It’s algae is 90%, including the giant kelp beds, kelp or algae.

RUTH KASSINGER: Kelp or algae, yep. They’re 150 feet tall, and they are algae, macroalgae.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. And how do they reproduce them?

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, the smallest ones, the cyanobacteria, simply divide. Microalgae, most of them divide, but some of them reproduce sexually. But don’t get any X-rated visions in your head because all they do is release spores that meet in the ocean and form new individuals. And that’s the same thing with seaweeds.

IRA FLATOW: Now, we’re in the summer. We’ve heard about these deadly algae blooms. What is that? What’s going on there?

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, most of these blooms are really manmade. It’s because algae are very happy in warm water, and they love nitrogen and phosphorus. And that nitrogen and phosphorus gets to them in large amounts because we’re putting too much fertilizer onto our farmland.

And so for example, in the Midwest, where there are lots of farms, the fertilizer washes off in the spring, finds its way into the Mississippi, then finds its way into the Mississippi, the mouth of the Mississippi, and into the Gulf of Mexico. And algae, with all that food for them– because that’s what they eat, nitrogen and phosphorus– they just go crazy and divide, and divide, and divide.

IRA FLATOW: Can algae live without water at all for any period of time, like bacteria might?

RUTH KASSINGER: Yes. Algae are pretty remarkable in that they can survive in almost any environment. There are algae that go dormant in the desert and might only reappear, get green, and reproduce with spring rains. There are algae that live only in the Arctic, and they’re actually pretty important algae. Hikers often see those. They’re a kind of algae– the variety is called nivalis. And they have red pigments that they use to capture sunlight, and they turn the snow red or pink when they bloom in the spring when there’s just a little bit of free water.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Our number, 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK, if you’d like to join us. You can also tweet us at @scifri. If algae are that hardy and can survive– I remember seeing algae growing in lakes in Antarctica when I was there many years ago– might we when we send probes to other planets or the moons of other planets and their oceans there, should we be looking possibly for algae?

RUTH KASSINGER: I think it’s a possibility. Why not? The algae can survive in very salty waters, and the scientists’ best guess are that the waters on Mars beneath the surface are extremely salty. That’s what helps keep them liquid. So they could be there. And certainly, scientists who are interested in colonizing Mars do think about taking algae with them to, one, create oxygen. And also, they can be full of protein, and other vitamins, and other good things for human beings. So we might be wanting to take algae with us to Mars.

IRA FLATOW: The title of your book, talking with Ruth Kassinger, is Slime, How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us. Where does the term slime come from when you talk about algae?

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, the slime that we are not very appreciative of on seaweeds, for example, is really a saving grace for the organism. When algae first evolved– and that was about 3.8 billion years ago– there was no oxygen in the air. And so there was no ozone layer.

And their DNA would have been fried if they hadn’t developed a kind of sunscreen. And that’s exactly what they did. It’s a polysaccharide sunscreen that protected cyanobacteria and all other microalgae and seaweeds. And I should add it is under investigation as a sunscreen for us.

IRA FLATOW: Very well. We talked about that earlier in the program. So that’s fascinating. So algae, by creating this sunscreen, allowed life to develop on the planet.

RUTH KASSINGER: Yes. Algae were absolutely critical to making our planet a livable place to be. Of course, they produced oxygen. And we all obviously benefit from that, and all oxygen breathing creatures. But they also created all the iron oxide on the planet. The seas used to be filled with iron. And it actually took more than a billion years for the oxygen escaping from algae to oxidize all the iron. So 83 billion tons of iron oxide on the planet is all due to algae.

And they were also critical in capturing nitrogen. If algae weren’t able to fix nitrogen, then there would be no life on the planet that was more complicated than a single cell.

IRA FLATOW: Quite fascinating. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Priscilla in Baton Rouge. Hi, Priscilla.

PRISCILLA: Hi, Ira. How are you?

IRA FLATOW: Fine, how are you?

PRISCILLA: I’m good. First time ever calling any kind of show. I like your show a lot. I appreciate all that you do. Here’s my question. OK? Like, in the definition of a plant, right? Don’t we usually think of a plant as something that makes its own food through the process of photosynthesis? Yet, your guest was saying that, like, well, they’re not really plants. So I’d like an answer to why it’s not a plant if in fact it does produce its own food–

IRA FLATOW: OK, Priscilla–

PRISCILLA: –through the process of photosynthesis.

IRA FLATOW: Because you asked for it, we’re going to answer that. Ruth Kassinger– thanks for calling. Thanks for being a listener. Ruth?

RUTH KASSINGER: Well, plants have roots, and they have what are known as vascular systems, which are tubes inside that carry water up and food down to the roots and to the leaves. Algae don’t have those things. Algae, because they float in the water, although they do photosynthesize, they don’t need those kinds of systems because the nutrients that they are getting come not from the earth, but they just pass right through the algae cell walls. So that’s the critical difference between algae and plants.

IRA FLATOW: We’re talking about algae with Ruth Kassinger, author of Slime, How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us on Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And like we talk about bacteria in the plural, algae is also the plural term, right?

RUTH KASSINGER: It is. Alga is the singular.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I know. We confuse those. We use them interchangeably. Now algae forms something called mucilage. It doesn’t sound very appetizing.

RUTH KASSINGER: No, that’s that stuff that is the slime that keeps them from getting their DNA fried. It’s not very pleasant to touch, although I have to say, after years of touching seaweed, yeah, actually, it’s perfectly fine.

IRA FLATOW: Now let’s talk about where algae– it’s all over the place. For example, the famous White Cliffs of Dover are not made out of little quartz sand particles, it’s all dead algae, right?

RUTH KASSINGER: That’s right. It’s algae and some other microscopic creatures. But yes, algae, after they photosynthesize, and divide, and eventually die, they sink to the bottom of the ocean, taking their carbon with them, which is a very good thing for our atmosphere. They constantly are cleaning the atmosphere of carbon dioxide.

But after millions– in some cases, billions of years– with tectonic plate movements, and volcanoes, and other shifts in the ocean crust, those layers become visible again. And that’s exactly what happened with the White Cliffs of Dover. That’s many, many feet of dead algae and other creatures.

IRA FLATOW: Now I know I used to have a small coral reef in my fish tank in my house. And I used to notice how the colors in there. And I learned that algae are crucial for the livelihood of coral, correct? And that they if lose their algae, they die off.

RUTH KASSINGER: Yes, it’s impossible to imagine. You cannot have a coral reef without algae. Corals are actually animals. And what we see and think of the coral part is really the calcium carbonate shell that they build up over time. But inside the calcium carbonate is a little animal. It looks a bit like an anemone, and it’s called a polyp. And that polyp comes out of the coral at night chiefly and snags little microscopic creatures, zooplankton.

But that’s not enough to feed a polyp. That’s only about 10% of the polyp’s diet. The rest of the food, the polyp gets from the algae that are living inside it. And those algae photosynthesize, produce sugars, and share them with the polyp.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, fascinating. Thank you. Fascinating. Well, we’ve run out of time. So much in Ruth Kassinger’s book. Ruth is a science writer based in Bethesda. Her new book is Slime, How Algae Created Us, Plague Us, and Just Might Save Us. A lot of great reading– great research on this, Ruth. Thank you for doing this from one algae lover to another.

RUTH KASSINGER: Thank you very much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. And you can read an excerpt up on our website at ScienceFriday.com/slime.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.