Blood In The Water: Shark Smell Put To The Test

17:00 minutes

Sharks are somewhat notorious for their sense of smell and ability to sniff out prey deep in the ocean. There’s that persistent myth that sharks can smell a drop of human blood from a mile away. But that’s not exactly true. While sharks can smell human blood, they are more interested in sniffing out what’s for dinner: other fish, crustaceans, and molluscs. Ocean currents also play a role in how far a scent can travel. However, shark noses are just as powerful as any other fish in the sea.

SciFri producer Kathleen Davis talks with Dr. Lauren Simonitis, a National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in biology at University of Washington and Florida Atlantic University, about her shark nose research, and what questions remain about shark snoots.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Lauren Simonitis is a Research and Biological Imaging Specialist at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This is Science Friday. I’m Sophie Bushwick.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: And I’m Kathleen Davis. Sharks are somewhat notorious for their sense of smell, sniffing out prey deep in the ocean. And their powerful noses sometimes get a bad rap too. There’s that persistent myth that sharks can smell the blood of humans from a mile away. Don’t worry, that’s not exactly true.

So what are shark noses actually capable of? Joining me now to talk all things shark smell is my guest, Dr. Lauren Simonitis, National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in biology at the University of Washington and Florida Atlantic University based in Boca Raton, Florida. Her research is featured in a recent episode of the PBS digital series Sharks Unknown. Dr. Simonitis, welcome to Science Friday.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Thank you guys so much for having me. I’m so excited to talk about shark snoots with you guys today.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So am I. So let’s start with some basics here. How good is the sense of smell of a shark compared to other fish?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So sharks and all fish smell really, really well. So they can smell 10 to the negative nine moles per liter. So basically, what that means is for one molecule of a scent in a billion molecules of water, that is how low of a concentration they can smell. But this kind of bursts a lot of people’s bubbles. But sharks actually have the same smelling ability as any other fish because sharks are fish, and they smell just like a fish.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow. OK, so does, like, the size of the fish matter here? Or we’re just talking about any fish.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Any fish. So all of our recorded sensitivities– so we can do these really awesome physiological tests where we put electrodes into a nose of a fish. We put different chemicals on their nose, and we see how low of a concentration we still get that brain activity that says, hey, I’m smelling something. And no matter what fish we test on, whether it’s a tiny little freshwater fish or a saltwater fish or a giant shark, we have the same olfactory sensitivity readings.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Wow. This is suddenly making me feel really bad for all the betta fish I’ve had who have been subject to some cooking experiments.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So I want to bust a big shark myth right here, right now. Can sharks actually smell human blood from a mile away?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So that is a very complicated question. Because when we think about smells in the water, the smell has to travel to the nose. So that depends on so many things in the water. It depends on currents. It depends on how turbid the water is, so how much movement is there, and where the shark is facing. So is it facing into the stream of the smell or the blood, which we call an odor plume? There’s a lot of factors that go into this.

The other important thing to think about when we think about how sharks are smelling human blood is that our blood is really different in our chemical composition than that of a fish blood or a squid blood or something like that, which sharks are actually keyed in on. So even though they may be smelling our blood, they’re not necessarily attracted to it the same way they would be to the chemicals in fish blood.

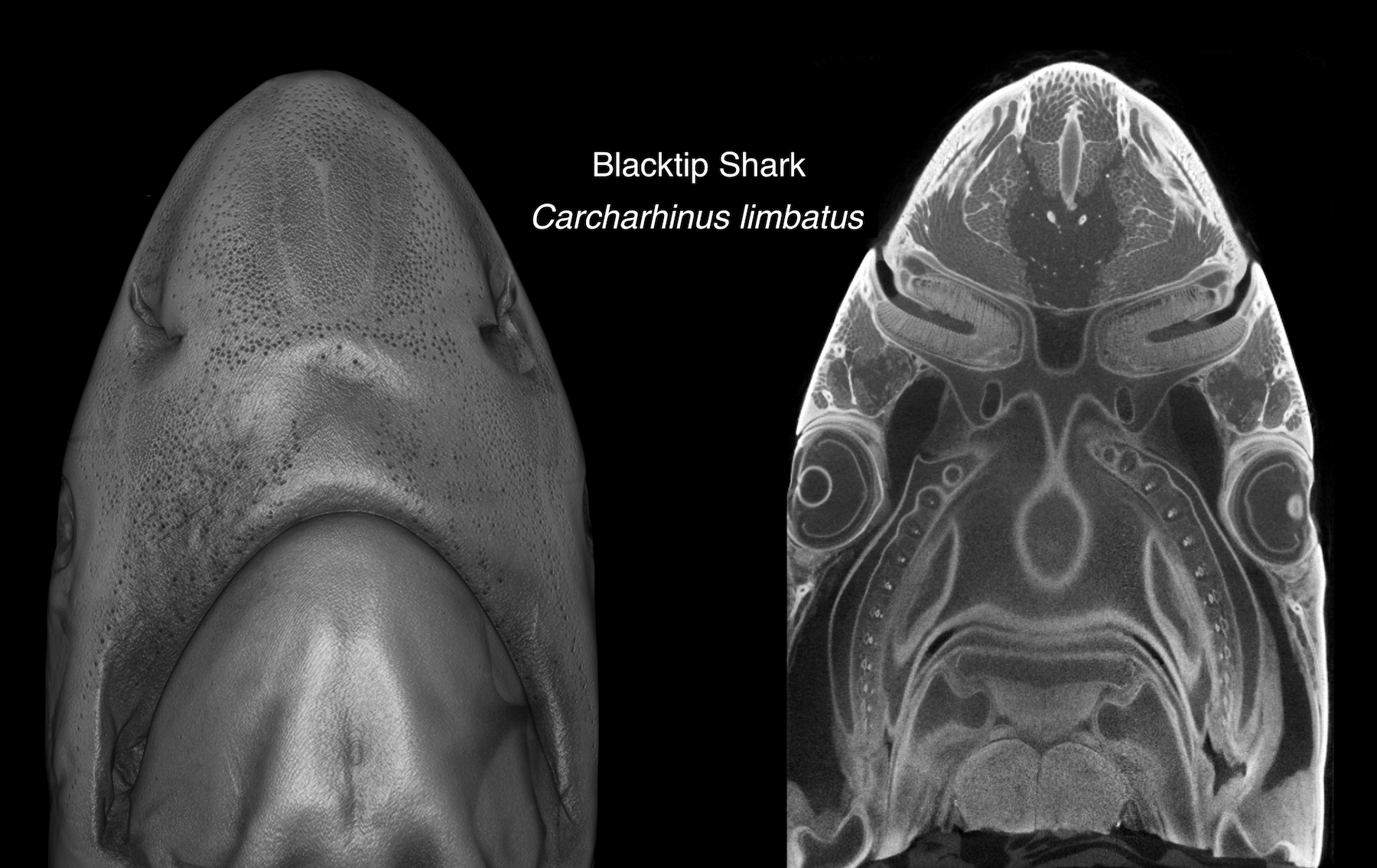

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So how exactly do sharks smell things? What do their noses or their snoots, as you said, look like?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yeah. So one important thing is that sharks are passive smellers. And what I mean by that is they can’t sniff. They don’t have musculature to [SNIFFS] sniff in we do. Instead, they swim through the water, and water passively moves into their nose. Their nose is also not connected to their respiratory system, so the way that they breathe. Like, we have ours super well connected. We don’t see that till a lot later in evolutionary history.

So as sharks are swimming through the water, water passively moves into one of their nostrils. And the reason I say that is because on either side of the shark head, they have two nostrils, one that allows water in– we call that the incurrent nostril– and then one that allows water out, and that is the excurrent nostril. So it’s kind of like this tunnel where water goes in one side, goes into their nose, their olfactory organs, and comes back out the other side.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK, so very different from our noses and the way that we smell.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yes.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: OK. So shark noses all look pretty different from the outside. Like, the hammerhead face looks different than the face of a great white shark. Is the nose anatomy similar?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So there is kind of a generalized nose plan. And how that works is we have two paired structures. They’re called lamella. And these lamellae, they are sitting on either side, and they’re connected by this center tube. So there’s a bunch of them stacked along this tube. You can kind of think of it as dishes stacked in a dishwasher. So there are all these plates back to back to back.

And as water flows through these tubes and between these lamella, these dishes in the dishwasher, there are olfactory receptor neurons that sit there. And when a chemical in the water binds to these neurons, the neuron sends a chemical signal to the brain that says, hey, I’m smelling something. I have this chemical in my little neuron grasp. So here is an electrical signal that tells you that I’m smelling this.

So that general plan is pretty conserved throughout all shark species. However, how that looks is different. So hammerheads, like you mentioned, are really long elongated tubes that have this really nice corridors to allow for water to pass by pretty easily. But then if we think of more of their pointy-headed cousins, they have more of a spherical shape, so less of a tube, more of a bowl.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So does that difference affect anything about if one shark can smell better than another?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So as far as we know, they’re equals. All of our physiological testing has told us that sharks, regardless of what their nose looks like, they all have the same smelling ability. And this is something that has really plagued sensory biologists or people that study the shark sensory systems for years.

Why do they have such different noses if it doesn’t mean that they smell better or worse? Like, it would make sense that a bigger nose has more area for smelling, so they should be better smellers. But that’s not the case. So what we think it might be is having to do with water flow. So sharks swim at really different speeds. They live in really different areas.

So if you think about an open ocean shark that is kind of swimming really passively in this big open ocean environment versus a shark that’s swimming in a coral reef that has all of these different water flows, they’re living in different flow regimes, which means that the water is flowing differently around them in their normal life. So we think that the way that their nostrils are shaped, the way that their internal rosettes– these beautiful rose-like structures of all these lamella attached to this tube– that has to do more with what water flow is doing rather than sensitivity.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So presumably, a shark can’t tell you what they’re smelling. But as somebody who researches this, how do you actually test the sense of smell of sharks?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So we use those physiological tests that I’ve told you before. But really, what that does is tell us if a shark can or can’t smell something. So we just get a yes or no answer. We don’t get a idea of how they feel about that smell. What we do is we tie physiology– so how that shark is smelling– with behavior, how they’re reacting to these smells.

So I have this experimental tank where I have these sharks swimming freely, and then I have these randomized points where I introduce a smell into the water. And I videotape them with this camera that sits overhead. And I use something called kinematics, which is basically how we understand how an animal moves through space. So if you’ve ever seen a behind-the-scenes of CGI or video games being filmed where people wear those little ping pong ball suits– so I give my sharks ping pong ball suits. I paint them with little white dots.

And I can digitize these dots in my software, and I get a little stick figure shark that swims around my tank. And I can use that stick figure to tell me how fast the shark is going. Is it turning towards or away from the smell? How quickly does it turn towards or away from the smell? And these kind of metrics tell me, how strong is this behavior? Is it an attractant? Is it a deterrent? Do they not care at all? And how strong is that reaction?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: What smells have you found sharks are especially interested in?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So sharks are especially interested in fish blood, squid blood, shrimp blood. But on that note, I will say that sharks are smart. They are like us. They can modulate their behavior. So just like us, if we are walking by a restaurant and it smells really good, we may be inclined to go in if we’re hungry. But if we just ate a giant meal, we’re not going to go after that. So there has been plenty of times where I’m literally dumping fish blood into the water, and my sharks are not interested at all because they just ate.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: They’re like, maybe give us a couple hours, and we’ll be a little better.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Exactly.

[LAUGHTER]

They get hungry pretty fast. So I get them interested eventually.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: There you go. So why is it so important to better understand shark smell and the mechanics around it?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yeah. So sharks smelling is really important because olfaction or the sense of smell in the underwater environment is one of the most important senses that underwater creatures have. It travels really far underwater, so it’s able to be carried on these ocean currents. It can diffuse at different rates. So the intensity of the smell changes how far it is.

And especially when you’re thinking about the other senses, like light or like sense of feeling or sense of taste or hearing, those are all really limited in the water. So olfaction is really, really important. It is a chemical sense which relies on the chemical makeup of the water. So when we think about things like ocean acidification or pollution, things that are changing the water chemistry, that is going to impact how animals, like sharks, are able to respond to chemicals in the water.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So despite sharks being not necessarily super interested in human blood, you are working on developing a shark repellent. Tell me a little bit about this. Why do we need shark repellent?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yeah. So while sharks may not be seeking out human blood, they can be interested in it. And not only are they interested in human blood, but they’re interested in fish blood. And if we are fishing, so we’re creating fish blood in the water, or we’re swimming near a hurt fish or something, sharks may come in and investigate.

Unfortunately, sharks don’t have hands, so they can’t pick something up and feel it and look at it. They investigate with their mouths. That’s where their electro senses are. That’s where their taste is. Their nose is up there. They’re really head-focused animals. So they’re taking these exploratory bites. And you can see that a lot of times, humans will be bit by sharks, but the sharks will not stay and chomp and eat them. They’ll just kind of take a bite and leave. Unfortunately, that bite doesn’t feel great for us.

So making sure that these shark-human interactions are done in a safe way where sharks can be in our area but not necessarily come and investigate us, that’s why it’s important to look into these preventative measures to keep sharks away from us, to keep sharks away from fishing lines and bait that can either hurt them or get fishers angry because sharks are now eating their fish catch. So there’s a lot of reasons to make sure shark and human interactions are done in a safe way.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: So how did you originally get interested in studying shark smell? This seems like a very specific area of research.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: It is. It is a very specific area of research, and it’s a very small world, which I’m super happy to be in. But I actually was not super interested in sharks. I was a sea slug aficionado. I’m, like, much more of a sea slug girly than anything. And sea slugs have really cool chemical defenses. So they have these chemicals that they can use to defend their soft, little, sedentary, squishy bodies from predators.

One species of sea slug– they’re called the aplysia species– they release ink, just like we see in squids and cuttlefish, octopuses, and even whales. There are inking whales. So there’s all of these different animals that produce ink. And ink is not only very visually distracting, but it smells bad.

So I was really interested in studying, why are all these animals evolving the ability to ink? So why are we picking this really dramatic, really costly defense? And it’s used between slugs, between cephalopods, and even whales. And I was really just using sharks as this common predator, this little thermometer to test how effective these different inks are. That’s what I did for my PhD.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: The sea slug to shark pipeline seems like you may be the only one. But I’m glad that that happened for you. There’s still a lot that we don’t know about shark smell, right? I mean, what’s the biggest question that remains for you?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: One of the biggest questions for me is still understanding that water flow part. So like I mentioned, we think that a lot of the way that a shark’s nose is shaped has to do on how water is flowing into that system. And we really only have one really intense study on how water moves through a shark’s nose, and it was done on a hammerhead, so a very weird nose.

So I’m really interested in looking at all of these different shark noses of so many different sizes, shapes, arrangements. How does that influence how water is flowing through that nose? And how does water flow impact their ability to smell?

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Do you have a favorite shark fact?

LAUREN SIMONITIS: So it’s not a nose-related fact. But whale sharks, their eyes are covered by dermal denticles, which are the teeth-like scales that cover shark bodies.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Whoa.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: It doesn’t really make a lot of sense to have teeth on your eyes, but they have them. And it’s super weird. Yeah, we didn’t know that until a couple of years ago.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: That is fascinating. That would be my favorite shark fact, too, I think. I want to ask really quick before we’re done– you’re a member of a group called Minorities in Shark Science. Tell me a little bit about this group and how you got involved.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Yeah. So Minorities in Shark Sciences was formed in June of 2020 by our four amazing co-founders, who are all Black women, who essentially took to Twitter and were like, does anybody else who is a Black woman study shark science? Help. We are alone. And they found each other, and they realized that there is a really big need for those of us who are not what you normally see on shark media programming, which is a cis straight white male, to have representation and to have community in shark science.

I will say that personally, I first entered the shark science world as a baby graduate student. And it was a super othering and negative and toxic space. And a lot of that was rooted in misogyny and racism. And I immediately said, I’m not a shark scientist. I am a slug scientist. I’m a convergent evolution biologist.

But I do not study sharks because I didn’t want to be lumped in with this negative community that I had experienced. And it wasn’t until the final year of my PhD when MISS, Minorities in Shark Sciences, was founded that I felt comfortable calling myself a shark scientist again because I found people who were like me and are allies who support our presence and our inclusion in this field.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Well, I’m glad that you found your niche in the shark science community because this has been a lovely conversation and such a pleasure to talk to you. Thank you so much for joining me.

LAUREN SIMONITIS: Thank you so much for having me. I will happily talk about shark snoots anytime.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: Perfect. Dr. Lauren Simonitis, National Science Foundation postdoctoral fellow in biology at the University of Washington and Florida Atlantic University based in Boca Raton, Florida.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.