The Lasting Allure Of Shackleton’s ‘Endurance’

17:27 minutes

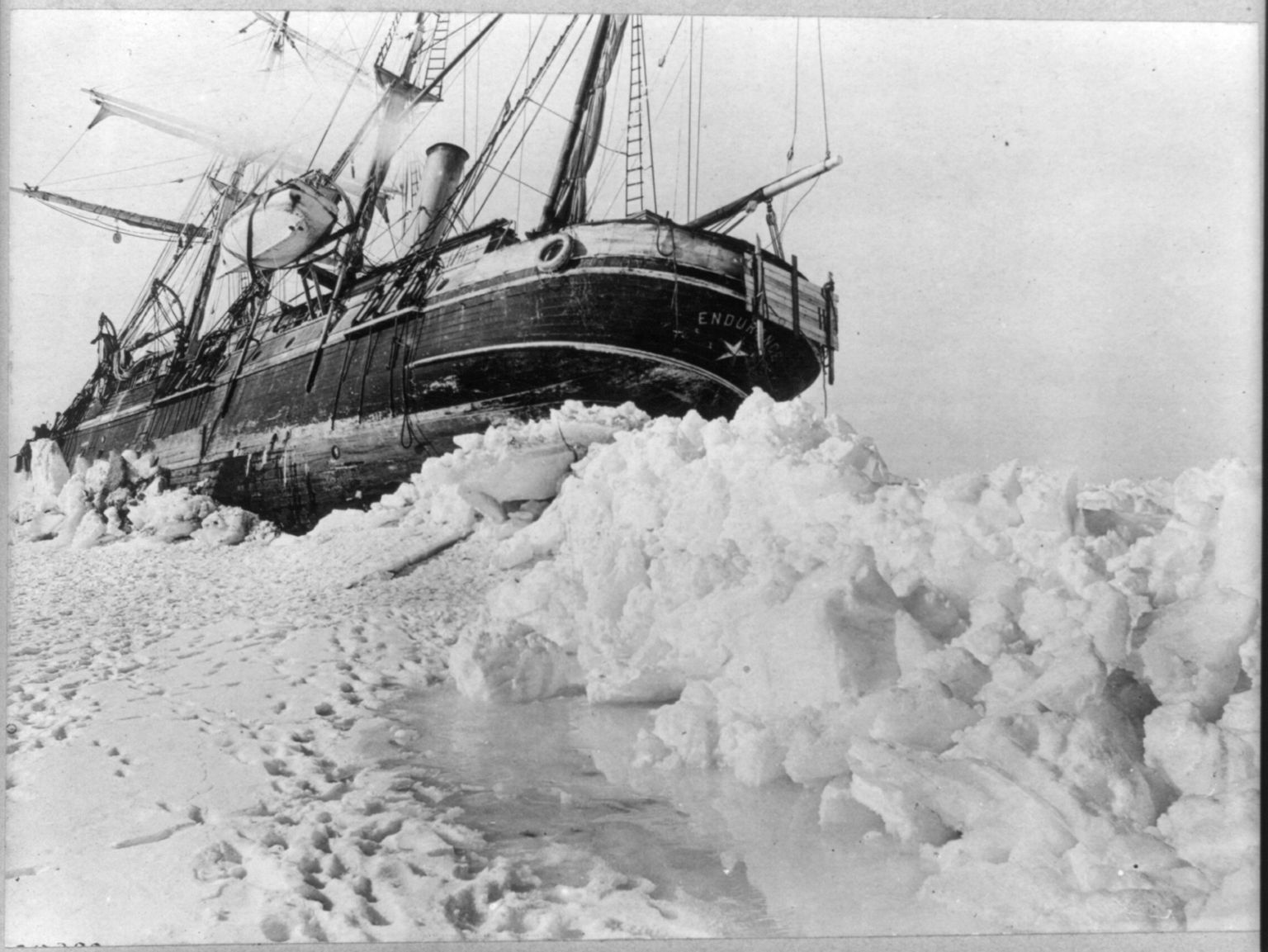

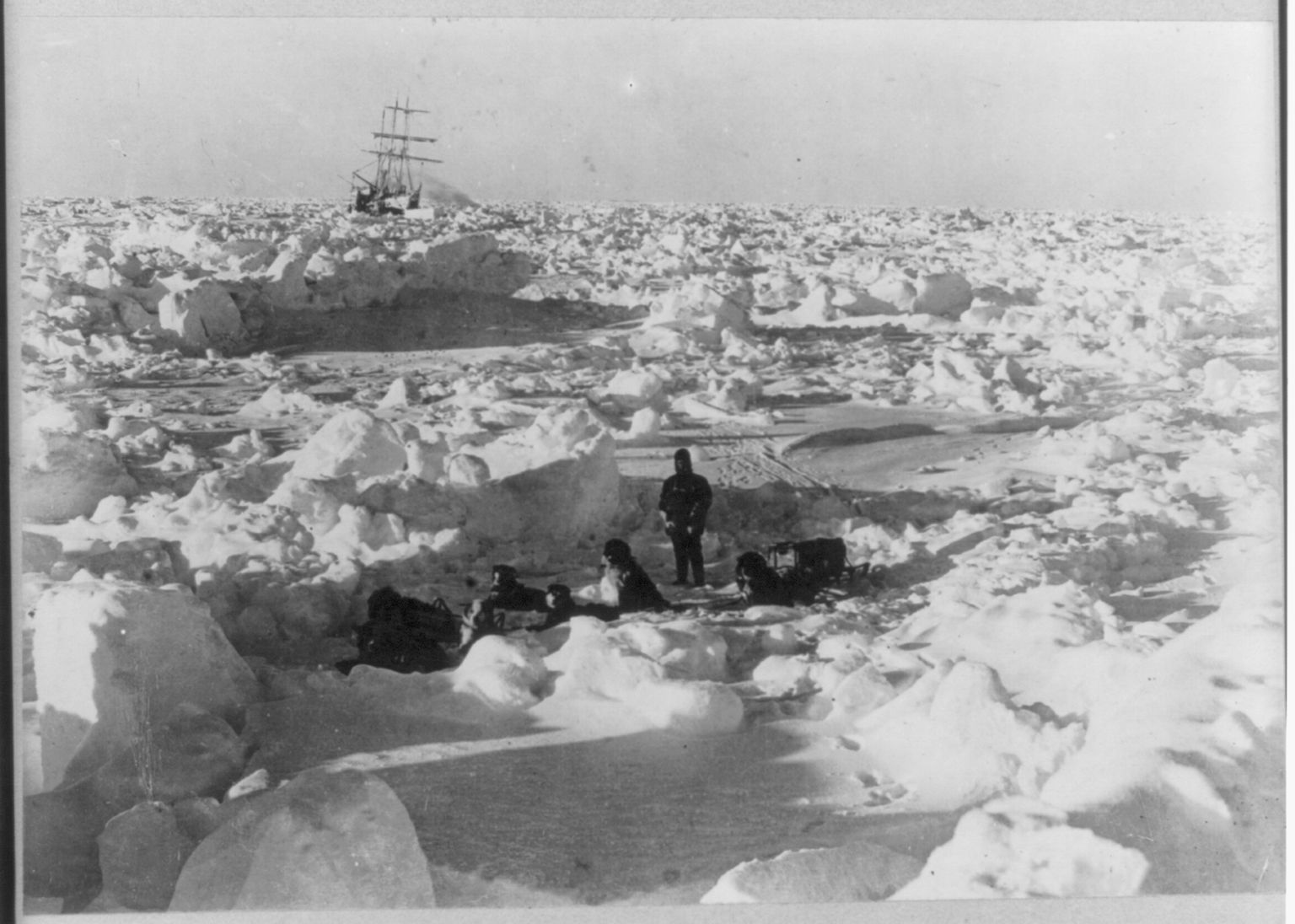

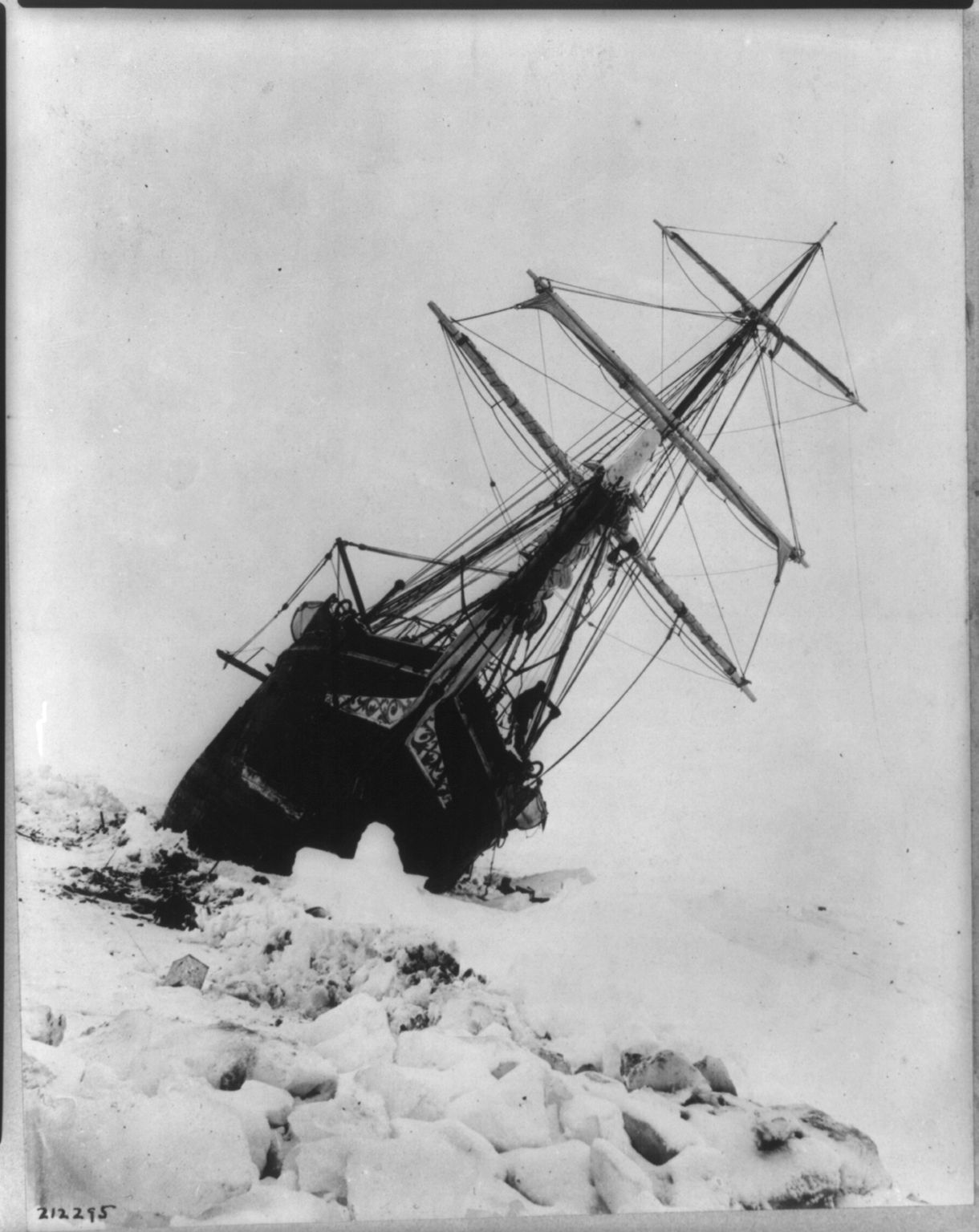

There are few stories about heroic survival equal to Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic rescue of his crew, which turned disaster into triumph. In August of 1914, 28 men set sail from England to the South Pole. Led by Shackleton himself, the group hoped to be the first to cross Antarctica by foot. However, their ship, the Endurance, became stuck in ice. It sank to the bottom of the frigid Antarctic waters, leaving most of the men stranded on a cold, desolate ice floe.

Shackleton, with five of his crew, set out in a small boat to bring help from hundreds of miles away. Finally, after many months of fighting the cold, frostbite and angry seas, Shackleton was able to rescue all his men with no loss of life.

Over the years, there have been many attempts to find the Endurance shipwreck. None were successful until a year ago, when the wreck was located for the first time since it sank back in 1915. Ira is joined by Mensun Bound, maritime archeologist and the director of exploration on the mission that found the Endurance. His new book, The Ship Beneath the Ice: The Discovery of Shackleton’s Endurance, is out now.

View more images of Shackleton’s last expedition from the Library of Congress.

Mensun Bound is a maritime archeologist based in Oxford, England.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. There are few stories about heroic survival equal to Ernest Shackleton’s daring rescue of his entire crew that turned disaster into triumph. In August of 1914, 28 men set sail from England to Antarctica. Led by Shackleton, they had hoped to be the first to cross the isolated continent by foot.

However, their ship, The Endurance, became stuck in the ice, was crushed, sank to the bottom of the frigid Antarctic waters, leaving most of the men stranded on cold, desolate land. Shackleton, with five of his crew, set out in a small boat to bring help from hundreds of miles away. And finally, after many months of fighting the cold, frostbite, and the angry seas, Shackleton was able to rescue all of his men with no loss of life.

Over the years, there have been attempts to find The Endurance shipwreck. But none were successful until literally a year ago when The Endurance was located for the first time since it sank back in 1915. Mensun Bound is a maritime archaeologist, Director of Exploration on the mission that found the ship and author of The Ship Beneath the Ice. Welcome to Science Friday.

MENSUN BOUND: Thank you, Ira. Glad to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let’s talk about your personal history with the story of Shackleton. You wrote that you grew up on the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic and that, “Everyone in my generation was a Shackleton enthusiast.” And you joined a crew of like-minded Shackleton nerds on your ship. You write, “We are a joyous bag of wonks on this ship, all card-carrying Shackleton fanatics.” Tell me more about this crew.

MENSUN BOUND: [LAUGHS] OK, I mean, at one level, we were a bunch of wonks. You’re right. But we were also a bunch of very highly trained minds. I suppose in some respects you might compare this whole grand exercise to finding The Endurance as the Manhattan Project or the moonshot or the Human Genome Project, by which I mean you had a group of technical specialists and very, very highly trained minds all brought together to crack this problem– how do we find Shackleton’s Endurance?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And it took you two missions to find it, right?

MENSUN BOUND: Yeah. We had to go in 2019. And that wasn’t a success at all. That was a disaster. We were using AUVs, Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. And our main search vehicle just disappeared without trace. And it was easily the worst moment of my life.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. And why did it take so long to find the wreck after all?

MENSUN BOUND: The main challenge was the ice– not so much the depth. It doesn’t really matter too much whether we’re looking at 1,000 meters or 6,000 meters. But the ice was quite a challenge, especially in 2019. It was really aggressive. It was thick, old, multiyear ice as tough as teak. And it was really sort of– you could feel the pressure. It was like you’re in the coils of a boa constrictor.

And towards the end there, winter was coming on. The ice was getting more and more muscular. And in the end, we lost the vehicle. And we spent three days charging around trying to find it. But in the end, the ice became too much. We had to get our tails out of there.

IRA FLATOW: So what did you do differently the second time in 2022?

MENSUN BOUND: Yeah. We learned a few lessons from our failures in 2019. Certainly, there was a sea change in our attitude of mind. I can’t speak for the others, but I do know this– I went in there feeling quite arrogant about things. I went in there like a bunch of Renaissance [NON-ENGLISH SPEECH] trampling all before us thinking, I can beat the ice.

And in the end, it was completely the opposite. The ice beat us. And I was completely humiliated and horsewhipped by the whole experience. The second time around, the ice was not nearly so bad. I mean, I couldn’t believe the change in just three years.

Last year, the ice was there, yes. But it was loose– a very, very loose matrix– a lot of leads, a lot of breaks in the ice. We just wriggled our way through to the search area with no problem whatsoever. Whereas in 2019, we had to break our way through. And yes, we got caught in the ice not once, but three times. But last year, it was simplicity Itself.

And I’m afraid it’s part of a trend. The ice is disappearing. But for that to have happened so fast in just three years, it was great news for us. But just terrible news for the planet.

IRA FLATOW: The journey of The Endurance was well documented by its crew. You talk about that. They had diaries that told the exact coordinates of the sinking. How far away from those coordinates did you find the wreck?

MENSUN BOUND: Yeah, well, I couldn’t say they were exact coordinates. I was the guy 10 years ago who was tasked with finding the wreck. And my first job was devising a search area. And I, like everybody else, imagined that a set of coordinates which had been left by the ship’s captain, a man called Frank Worsley, I, like everybody, thought that they were an observed position, by which I mean they were taken using a sextant.

In fact, there were nothing of the kind. It was an estimated position because he wasn’t able to get a sight on the sun until the day after she sank. So he estimated his position. He guessed how fast the ice was moving, what direction the ice was moving. And he applied what we call an offset to his position as of the next day. But in the end, you know what? He wasn’t far wrong. He was just over 4 nautical miles away from where he said he was, which all things considered, isn’t bad.

IRA FLATOW: What was the reaction when The Endurance was located?

MENSUN BOUND: Believe it or not, myself and my friend John Shears were actually out on the ice at the time. We’d come through a period of really very difficult weather. Temperatures had dropped to -40 and -50, which is– this is centigrade by the way, guys. I think you do Fahrenheit in the states. But this is centigrade. This is seriously dangerous stuff.

In my case, it popped some of my filling. There was one guy there whose eyelids got frozen closed. And the guys in the back deck, they were really, really suffering. And then shortly after 4 o’clock in the afternoon, an image appeared on the sonar cascade in the control booth at the back of the ship. And it was clearly something that was man-made. And of course, the only man-made thing in the center of the Weddell Sea is The Endurance.

So they called in one of the sonar experts, a guy called Francois who used to be a Cold War submarine chaser in the North Sea. He took one look at it, and he said, [NON-ENGLISH SPEECH]– it’s her. And a guy called Nick Obinson, who’s in charge of all sub-sea activities on the ship, he’s an old friend of mine.

And he just strode up. And he thrust his iPhone right into my face. And he said, gents, let me introduce you to The Endurance. And on the screen was this perfect little high frequency, high resolution image of The Endurance seen from above perfectly delineated.

And it was just– I don’t know– totally explosive it was, that moment. I mean it was just– I don’t quite know what you can liken it to. It was just like sunbursts of just pure, undiluted joy or euphoria.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about the condition of The Endurance when you finally saw it. I know you specialize in diving on shipwrecks. You’ve seen a lot of them. What condition was The Endurance in?

MENSUN BOUND: Yeah. You’re right. I’ve seen a lot of shipwrecks in my time. It’s all I’ve ever done my entire adult life. And I think I’m safe in saying I’ve probably seen more deep ocean shipwrecks and wooden shipwrecks than anybody I’ve ever met in my profession. And usually, deep ocean wooden shipwrecks have broken up from impact.

But when we launched this project back in 2018, it would have been, I did make four predictions. This was at the Royal Geographical Society in London. I said that she’d be upright. I said that she’d be well proud of the seabed. I couldn’t see any reason why she should be absorbed by the mud.

And I knew that if she was sinking and dragging all those broken sails and masts behind her, that they would impose a drag on the falling ship so she’d go down keel first. And I also said that she’d be three-dimensionally intact. I was going out on a limb there.

But I did say that the greater probability was that she’d be three-dimensionally intact rather than broken open simply because we’d found her construction details at an archive in Norway. And she was, at the time, said to be the second best or the second strongest non-naval wooden built ship in the world. And when I looked at those plans, I realized that if ever there was a ship that could withstand the impact of the seabed, then it was The Endurance. So I said she’d probably be three-dimensionally intact.

And then I said she’d be in an excellent state of preservation. And there, I knew I was pretty safe because there are no wood-consuming marine parasites in the Weddell Sea. I mean, yes, there’s always bacterial degeneration. There’s always chemical decay and mechanical decay. But the main things which destroy wooden shipwrecks are ship worm, teredo worms. They are to wooden ships what deathwatch beetles are to timber frame houses or moths to cardigans, something like that.

But we didn’t have any of those in the Weddell Sea. And sure enough, when we saw her for the first time, I just couldn’t believe that you could see her paintwork. It was as if, as the captain said, Captain Knowledge Bengu said, it was if somebody just kind of laid her out on the seabed and just said, wait. Wait until you’re discovered.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. You write that water is a surprisingly good preservative. And in fact, how deep it was, where the lack of oxygen was there–

MENSUN BOUND: And the cold.

IRA FLATOW: And the cold it, it looked like the day it went down. It looked– [LAUGHS]

MENSUN BOUND: You could count the ships fastenings, Ira. It was just unbelievable. I’ve never, ever seen a shipwreck as bold, as beautiful, as together as The Endurance.

IRA FLATOW: You also write that if you were “asked to choose what for me, was the most uber-awesome moment of the archaeological inspection dive, I would, without any hesitation, say it was when I found myself staring down three rough cut holes through the main deck.” Why were those holes so important?

MENSUN BOUND: Oh, yeah. Right. So yeah, we only did two dives on the ship, believe it or not. The first one was to secure the data. And the second was the archaeological dive. And this is when we were going to see the ship for the first time in real time looking through the cameras on the vehicle at it. And we approached from the stern.

But then we went up and over the stern and along the deck. And as we going along the deck, one of the French guys, guy called Jim, said to me, look. Ice damage. But I knew exactly what they were from the diarists. And I said to Jim, I said, no. It’s not ice damage. Those are the holes which saved their lives because when they left the ship, they didn’t have very much at all in the way of supplies with them.

It was all down in the twin decks area. And they very quickly realized, once they left the ship, they didn’t have enough to sustain them. Yes, there were seals, and there were penguins. But with winter coming on, those seals and penguins would become more and more sparse.

So they suddenly realized they were in trouble. And it was the photographer, a guy called Hurley, who realized that maybe, just maybe they could actually cut a hole through the deck of the ship. And he knew where a lot of the supplies were. So that’s what they did. And over two days, they extracted three tons of food. And it was that food which saved their lives.

IRA FLATOW: When Bob Ballard, who discovered the Titanic, was on our show years ago, he said that he was sorry that the exact location of the Titanic had been published as it led to a great commercialization of the site, which he believed to be a graveyard that should be respected. And he hated that people were scavenging, recovering objects from a graveyard. What are your feelings about bringing up The Endurance or preserving it or anything about the future of it?

MENSUN BOUND: I share Bob’s feelings. In fact, I haven’t said this before, but what happened to the Titanic and his personal upset at what happened to the Titanic was one of the reasons why we were so anxious to find The Endurance. I mean, The Endurance search was 10 years in the making. It was myself and a friend of mine. In fact, it was my friend who came up with the idea 10 years ago in 2012.

And I knew that the time would come when she would be found. And I was anxious that she not be turned into this sort of help yourself wreck site, which is what pretty much happened to the Titanic. It sort of became a bit of a smash and grab afterwards. And Bob really had no control over the mayhem that followed.

And I and my colleagues, we were very concerned that it be found by a responsible body with archaeological objectives and that it be protected quickly. So yeah. I’ve read Bob’s books, and I sympathize with him completely.

IRA FLATOW: So what will happen? Do you think that people will scavenge The Endurance?

MENSUN BOUND: Well, not everybody would agree with me, but from a lifetime of experience of shipwrecks, I know this– that when they found– ah. Right now, it is protected by the ice and the cold. But this year alone, we had one ship right over the wreck in January. And we would see that in the satellites in the Falklands.

And the way the ice is disappearing, that protection will soon be gone. So it’s a huge worry. It really is. I have some bitter experiences of having seen what happened to wrecks. I remember after the first wreck I have excavated, a ship off the Tuscan island of Giglio off northwest Italy, when I finished that job, the superintendency of archaeology for Tuscany told me about a new wreck which had been found– a medieval ship, absolutely intact and perfect.

For various reasons, maybe because I was young and bit ignorant, I didn’t think it was that important. I thought if it wasn’t Roman or Greek, then it didn’t have archaeological significance. And I turned that wreck down. And several years later when I smartened up, I went back with my wife. And we looked at that wreck again.

And in the five years between when the superintendent of archaeology took us there and when we saw it again, it had been completely erased. All that was left was just this brown stain in the sand. So I could tell all the stories like that. So I worry about this a lot. But right now, it’s safe.

We have some very responsible organizations, in particular the UK Antarctic Heritage Trust. We have other archaeological organizations within England which are putting together a protection plan. So she’s in good hands. I have no plans to go back, nor does the Falklands Maritime Heritage Trust.

IRA FLATOW: I want to end this interview talking about the saga of Shackleton’s journey. You weave it throughout the book. And at the end of your story, you’re standing next to his grave on South Georgia Island.

And you write, “He could have reached the Pole. He could have claimed the prize. But he did not. He got to within 100 miles of it. Why did he not do it? He didn’t do it because he knew that if he did, on the way back, men would die. And that is who Shackleton was. Here beside his grave, it occurs to me that in all Shackleton’s expeditions into danger, which he himself led, the only life he lost was his own.” A fitting epitaph, do you think, Mensun?

MENSUN BOUND: Yeah. Especially when you read it. Yeah. [LAUGHS] That’s precisely how I feel. He was a remarkable man. He could have reached out and claimed the prize, the discovery of the South Pole. But he got to, what was it? 97 miles of Pole and he stopped. And he stopped because he knew that on the way back, men would die.

And indeed, we know it would have happened because on the way back, they had to leave a couple of men behind and make a dash to the ship to get help. And then Shackleton turned around and went back with the relieving party to pick up his men where he had left them. In other words, Shackleton could have made that last dash to the Pole, and he would have got back himself alive. But certainly, those two guys, they would have died.

IRA FLATOW: Mensun Bound, thank you for taking time to be with us today.

MENSUN BOUND: It’s a great pleasure.

IRA FLATOW: Mensun Bound, a maritime archaeologist and director of exploration on the mission that found The Endurance. His new book, The Ship Beneath the Ice, is on sale now. I highly recommend it.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.