Seven New Chances for Life in Space, Just 40 Light-Years Away

16:51 minutes

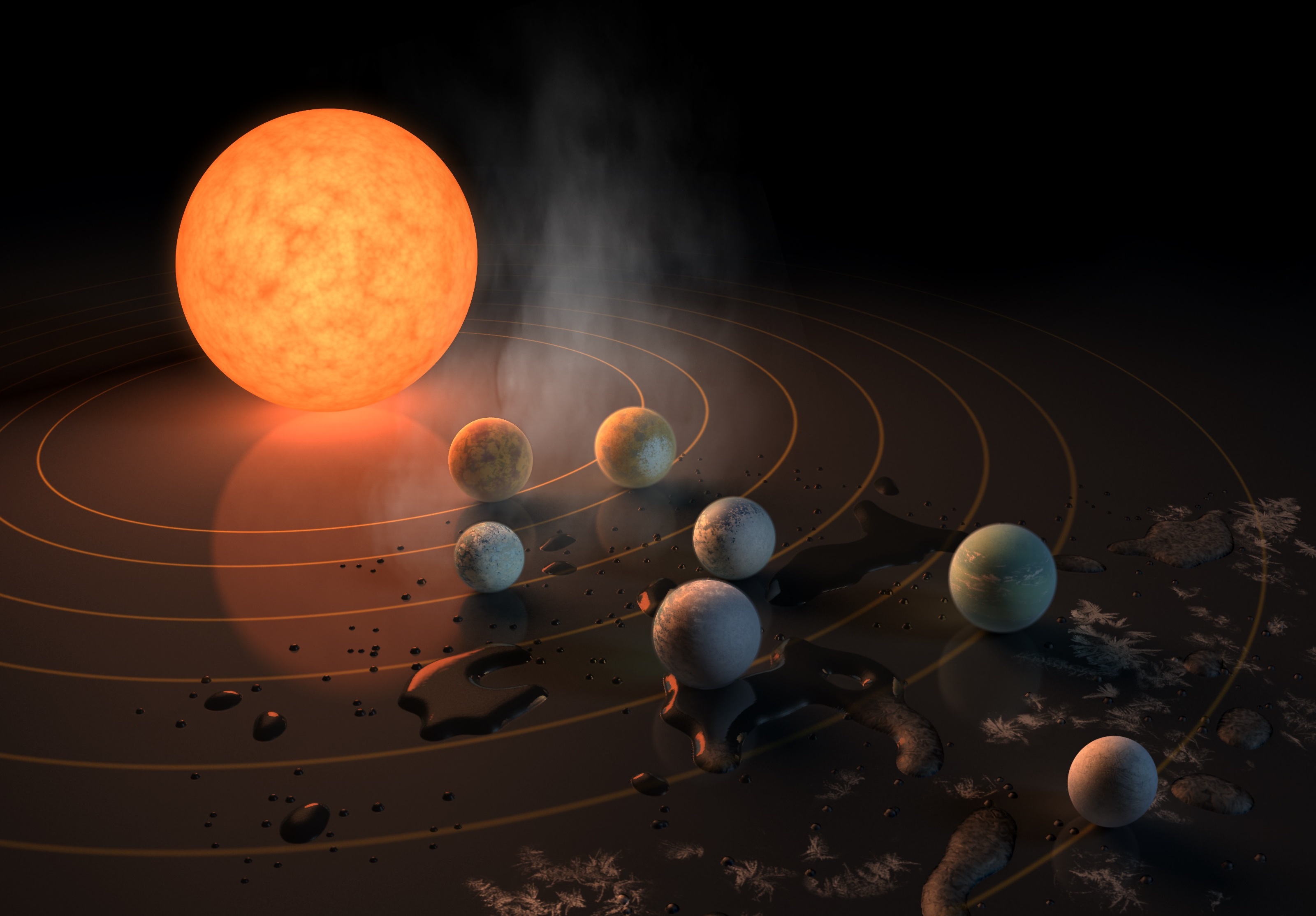

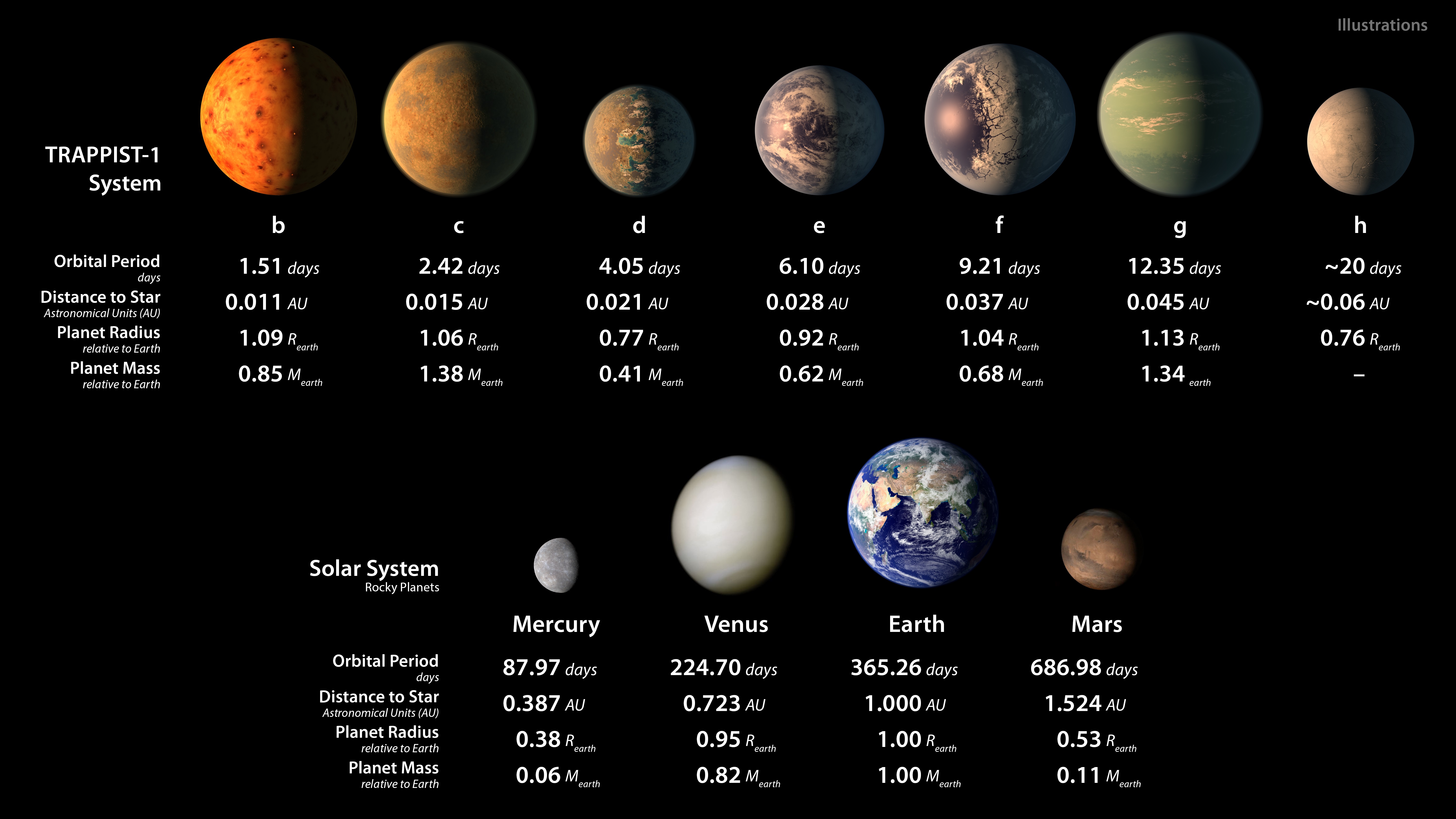

It’s not often that scientists make a discovery so big that the whole internet is talking about it. But NASA caused a stir this week, with its announcement that seven exoplanets have been found orbiting a nearby dwarf star—and that three of them may be “Earth-like.” That means they could have a rocky surface with liquid water and an atmosphere capable of supporting life.

Astronomers discovered three of the planets orbiting the dwarf system, called TRAPPIST-1, last May. They detected the planets by measuring the amount of light that the star, located 40 light-years away, emits. Each time the orbiting planets passed between the star and scientists’ terrestrial telescope, the starlight dimmed.

Following that observation, astronomers took another look at the TRAPPIST-1 system, this time using the Spitzer space telescope, over a period of 20 days. They discovered not three, but seven Earth-sized planets orbiting the dwarf star.

Scientists suspect that these seven planets have the right conditions for life, based on their position in the “Goldilocks zone”—that is, the habitable zone—of their host star, which is classified as an “ultra cool” dwarf, and much colder than our sun. The planets are also a lot closer to their star than even Mercury is to ours. Astronomers will follow up the discovery with observations of the planets’ atmospheres, which should reveal if there are any gases present that are indicative of life. Exoplanet researcher Sara Seager of MIT joins us to discuss the historic exoplanet finding.

[Scientists think there might be an undiscovered planet in our solar system.]

Plus, are you interested in the search for exoplanets but don’t have access to a space telescope like NASA’s? The online citizen science organization Zooniverse has data from the Kepler telescope that anyone can mine. Participating citizen scientists have even published papers on their discoveries. Laura Trouille, the director of Citizen Science Projects and a co-Investigator for Zooniverse at the Adler Planetarium, explains how you, too, can be a planet hunter.

Sara Seager is professor of planetary science and physics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Laura Trouille is Director of Citizen Science and Co-Investigator for Zooniverse. She’s based at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, Illinois.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

It is not often that scientists make a discovery so big that the whole internet is talking about it. It even made the front page of Google. Now, this week NASA announced that not one, not two, but seven new Earth-sized planets have been found orbiting a nearby dwarf star. They’re in the so-called Goldilocks zone– not too hot, not too cold. The perfect temperature for supporting life.

So how will scientists ever know if these seven planets are similar to Earth? They may be the same size, but maybe similar to Earth. And if they can sustain life, what do we do then? Well, if there’s one person who can answer those questions, it’s my next guest, Dr. Sara Seager, professor of planetary science and physics at MIT. Welcome back to Science Friday, Dr. Seager.

SARA SEAGER: Thanks so much, Ira. It’s great to be back.

IRA FLATOW: It’s good to have you. Now, news of these seven exoplanets, as I said, are all over the internet this week, even the Google Doodle got on board. But we have found exoplanets before, so why all the excitement about this discovery?

SARA SEAGER: Well, there’s many reasons why. The first, as you’ve already mentioned, that there are not just one, but seven Earth-sized worlds. And it’s like a jackpot, really, for being able to find out the answers to questions we’ve had for millennia.

IRA FLATOW: These planets are 40 light years away, so how are scientists able to find them?

SARA SEAGER: Well, they found them with– so, 40 light years seems far and away because it’s so far away. It’s hundreds of millions of miles away. But it’s close, astronomically speaking. And scientists are able to find it by just monitoring the brightness of the star and looking for a drop in brightness, just in case a planet were to go in front of that star. And it turned out that not just one, but seven planets go in front of the star, as seen from Earth.

IRA FLATOW: Now, this was from a star, a cool dwarf star. And is this the first time that scientists have looked at that kind of a star?

SARA SEAGER: In this particular star, yes. But there’s a lot of stars that are called– they actually have the letter M– M-dwarf star. They’re red stars. They’re cooler, they’re dimmer than the sun. But out of all of that category, this star, it’s not just called cool dwarf star, it’s actually called ultra-cool dwarf star.

IRA FLATOW: Ultra?

SARA SEAGER: Yeah, you start to run out of adjectives. This star is so small and so cool, if it were any smaller, any lower mass, it wouldn’t even be a star. It wouldn’t be able to sustain fusion in its core.

IRA FLATOW: Why, this is a star and a cool star. And you know, it’s like Hollywood. You know, it’s like, it’s cool, man.

SARA SEAGER: It is, it is. But the leader of the project actually purposefully went after the smallest type of stars out there because it’s easier to find small planets around small stars than it is small planets around Sun-like stars.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. How come our star has only one Earth, but this star could have seven?

SARA SEAGER: Aha. Well, that’s a great question, Ira. And I’m thinking, actually, if there are intelligent beings elsewhere that are looking back at us, perhaps they’re on their own radio show today, saying, hey, we just found three planets, three Earth-sized planets. And they’d be thinking of Venus, Earth, and Mars.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s what I was thinking–

SARA SEAGER: Yeah, Mars is actually pretty small, but at this point, that would be the equivalent. It’s like, wow, we found all these planets, they’re all Earth-size, some are in the habitable zone, but we need a further look to really narrow it down.

IRA FLATOW: So, how come they have– and so you’ve lined up seven orbits and seven planets around this star?

SARA SEAGER: Yes, actually. And we actually knew about, thanks to Kepler and other much more distant stars, we’ve seen not quite that many planets in a row, but it’s amazing. It’s so different from our solar system, but for some reason, there are planets all lined up, all compactly packed tightly together.

And in this case we think– it’s so new, though, people haven’t really been able to think about it in great detail yet, but we think the planets must have interacted with each other in a kind of planetary dance. And they came to their lowest energy state by being all lined up together.

IRA FLATOW: So, I guess the first thing that we always ask about is, how similar is it to Earth? I mean, and the first thing we talk about is water. Is there water? How do we test for that?

SARA SEAGER: OK. Well, first, I’m really glad that you’ve been able to articulate “similar to Earth,” because we have no idea whether they’re going to be like Earth or not.

But we do know how we can find signs of water, and that is by finding water vapor in the atmosphere. Because water vapor in a small, rocky planet shouldn’t be there. Because the water vapor would get split apart by particles from the star, by photons from the star, and the hydrogen would escape to space just like a child who’s holding a helium balloon might let it go and it floats away.

Hydrogen is light. It shouldn’t be on those planets. So if there’s water vapor, then there’s most likely a liquid water ocean. And water vapor, by the way, on Earth it’s our biggest greenhouse gas. It’s a very powerful gas. It’s absorbing very strongly and makes giant signatures in the atmosphere.

IRA FLATOW: So, how soon can we find out?

SARA SEAGER: Now, this question really depends on what nature has in store, because if some of them have literally a giant, whopping water-vapor feature, we might– and that’s a kind of very remote possibility– see water vapor with the Hubble Space Telescope. And indeed, even as we speak, there is Hubble data waiting to be analyzed and more on its way.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I know the new Webb Telescope is under development. Is that going to be made specifically for looking at exoplanets like this one?

SARA SEAGER: Well, Webb was started 25 years ago, actually. It takes a long time to get a big, fancy, sophisticated space telescope ready. So exoplanets weren’t really known about back then. But yes, James Webb Space Telescope, we see that as our powerhouse, our new Hubble. It’s going to do incredible things, including being able to study many of these planet atmospheres in detail.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if this is 40 light years away, and we think there might be signs of water or whatever, that’s actually in the realm of one person’s life, a round-trip message, isn’t it? 40 plus 40 is 80.

SARA SEAGER: Yeah, it might be a bit of a stretch, but yes, we’re getting there. But I do want you to know that there are lots of planets out there. And we’re starting to think that there are planets– actually, we’re confident that there are planets around every star.

And so, for example, Proxima Centauri, our very nearest star at four light years, also has a planet. And that planet, we know even less about it, actually. We just know it’s minimum mass. It’s not transiting. It’s not going in front of the star, so we can’t probe its atmosphere. But we definitely will see more to come.

IRA FLATOW: And what are you most curious about? I mean, as a planetologist, you must be just jumping up and down about a discovery like this.

SARA SEAGER: Well, there’s two things, Ira. One is like the “go for the gold”– is there life on those planets? I’d say that’s what I’m most curious about. But that kind of science fiction type of thoughts aside, really, it’s like, what are these planets?

I mean, are they like Mercury? Have they lost their atmospheres due to the craziness of the star? Or are they really just nice worlds like Earth with oceans and continents and clouds, and things like that. I think even just knowing the very nature of these planets is what we’re itching to get at.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And if scientists are able to confirm the presence of water, or let’s go one step further, even life on one of these planets, do you think that would accelerate research into deep space travel?

SARA SEAGER: Absolutely. And we’re even seeing that acceleration now. I just want to go back one second. We would unlikely to be able to confirm life, but we can find highly suggestive evidence of life. In fact, already, believe it or not, just the exoplanets already known have galvanized people to actually take space travel and interstellar space travel more seriously than ever before.

There’s a thing we call “the giggle factor.” That means if I tell you something– I’m sure this happens a lot on your show– you just start laughing because it just sounds so silly. So the giggle factor of interstellar travel is diminishing.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, but it’s so far away. I mean, that’s why we giggle at it. Tell me how that can happen.

SARA SEAGER: Well, I can tell you about some of my colleagues who are working on a project called Starshot. And that actually is a breakthrough foundation project. What they’re thinking is– actually, there’s still a lot of history behind this idea. But it’s to send thousands of tiny little spacecraft, that you could fit one in the palm of your hand.

And they do have 19 challenges. They’ve listed them all out for all of us to read and ponder. But if they can put them in space and beam intense radiation at them, and accelerate these to 20% the speed of light, then a trip to Proxima Centauri would be 20 years, which is still a very long time, but not as long as 80 years.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re saying we would push these tiny little things with light. We’d push them and accelerate them that way.

SARA SEAGER: Right. Push them and accelerate them. And they would go to Proxima Centauri b and they would snap a few photos and send them back to us.

IRA FLATOW: Do you ever wonder that maybe we don’t want anyone to know that we’re here?

SARA SEAGER: I don’t know. I like the thought that if they’re intelligent enough and sophisticated enough, they already know we’re here.

IRA FLATOW: OK. I’m going to bring on another guest. This is so fascinating. Laura Trouille is Director of Citizen Science and co-investigator for Zooniverse at the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. Dr. Trouille, welcome to Science Friday.

LAURA TROUILLE: Happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: You excited by this as well as Dr. Seager is?

LAURA TROUILLE: Incredibly. And I love your show. I mean, every week you celebrate discoveries in science and the process of science.

And so, what’s fun for me is to be able to come on and invite your listeners directly to participate in the exploration and discovery process. So, pretty much every topic you cover, including this exoplanet discovery, your listeners can jump in and help researchers directly with it. And that’s through citizen science.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Tell us how our listeners can be involved with this.

LAURA TROUILLE: Yeah, so specifically for exoplanets, if that’s your thing, you can go online right now into planethunters.org and help the research team sift through Kepler space satellite data and identify previously undiscovered exoplanets. And there’s already been a number of discoveries led by just members of the public, through this online site, looking at Kepler data.

IRA FLATOW: When you mean Kepler data, we are actually looking at photos of possible things, or is it numbers and stuff?

LAURA TROUILLE: So, it’s a similar process to this week’s exoplanet discovery. The researchers looked at the light curves from the star, and were looking for dips in that light curve. And whether you’re a five-year-old or a 95-year-old, our ability to recognize patterns is really sophisticated. And so it’s a super-low barrier to entry. You can just go onto the site, look at a light curve, just how light changes over time, and look for dips.

And through that process, a couple of years ago now, some of the volunteers on planethunters saw a four-star system with planets around it. And that was the first of its kind, and it’s only because of their human eye ability to recognize patterns that they saw this. And it was something that the computer-automated algorithms hadn’t been trained to look for yet.

IRA FLATOW: So they got to be part of a research paper, then, that got published.

LAURA TROUILLE: Yes, definitely. They were part of the analysis and very much co-authors on the paper.

IRA FLATOW: Sara, how do you feel about these amateurs getting involved in this work?

SARA SEAGER: I love this. And you have no idea how important they are. Because we’re good with computers, we love programming, but honestly, we can only program mundane, everyday things. It’s really hard to spot that really unusual star.

And I just want to add that I tell all my people about Planet Hunters– from my children, to my students, to post-docs, to my faculty friends– anyone who wants to work on exoplanets and finding planets with the transit techniques should really start there, because getting used to data and seeing tons and tons and tons of real data is really critical.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International.

Laura, how much time does an average person need to devote to this kind of project?

LAURA TROUILLE: It really ranges from volunteer to volunteer. So we have 1.5 million people who are registered volunteers through our umbrella organization site, which is Zooniverse. And some people come in and just spend five minutes. And that’s a huge and important contribution. And they can do, on Planet Hunters, for example, they can do a couple of classifications.

Some people do 50,000 classifications each, and so they spend hours on the site. But whether it’s a little bit of time or a lot of time, all of it is useful. And importantly, it’s not just classifying, but for those who want to engage more deeply in the process of science and discovery, they can go into the discussion forum and interact directly with the research team and ask questions and answer questions together.

IRA FLATOW: Citizen science, it’s great. It’s a great idea.

Sara, where do we go next with your planets, your seven planets here? What comes next? What will be the next step?

SARA SEAGER: Well, in the short term, I’m sure there will be a flurry of speculative research papers on pretty much every topic, from how they formed, to whether or not they have atmospheres, to what the chances for life are. But I would keep your eye on any results coming out of the Hubble Space Telescope. And notwithstanding that, we’ll have to have a bit of a pause for getting real data for a bit longer.

But actually, Ira, when we make a discovery like this, really, people put every kind of telescope on the system. And there’s the Kepler K2 mission that right now is actually observing the field of stars where the TRAPPIST-1 star is. So there’s some chance– some outside chance– they might even find more planets in the same system.

IRA FLATOW: And what constellation is it near?

SARA SEAGER: That’s a good question. It’s actually near the Southern Hemisphere, but I don’t remember offhand.

IRA FLATOW: So I can’t go in my backyard and put my little Celestron C8 on it.

SARA SEAGER: No. It’s a very faint star. It’s actually, when we talk about magnitudes, it’s magnitude 18 or 19. It’s super faint and super dim and invisible wavelengths.

IRA FLATOW: Not going to be like the Orion star, Betelgeuse.

SARA SEAGER: No, it’s not.

IRA FLATOW: It’s not going to see that. And Laura, how do people sign up if they want to be citizen science?

LAURA TROUILLE: So, you can just go directly to planethunters.org and you can sign in, or you can participate without signing in. And then if exoplanets isn’t your thing, there are 52 active projects on Zooniverse, meaning 52 different research teams with cutting-edge science, inviting you to help. So, from cancer research, to ecology, to climate science, to transcribing Civil War telegrams. So there’s a whole range of topics which you can help scientists directly with.

IRA FLATOW: I’m reminded of– we had an author on recently about a book. The women who volunteered at the turn of the century, 100 years ago, looking at the plates. Looking for all the moving stuff.

LAURA TROUILLE: Yeah, the Harvard Computers. There’s a long history of citizen science, and it’s because anybody can do this. I have two little girls and it’s just embedded in us, the curiosity and wonder. And so it’s now just giving people access to that through sites like Zooniverse, to participate directly.

SARA SEAGER: And Ira, I just actually checked. It’s Aquarius. It’s in the constellation Aquarius.

IRA FLATOW: Of course.

SARA SEAGER: TRAPPIST-1.

IRA FLATOW: Of course it’s in Aquarius. We people from the ’60s would have guessed that the dawning of the–

SARA SEAGER: Right. That’s exactly what one of the comments was that I read recently– the age of Aquarius.

IRA FLATOW: It makes only sense, history repeating itself. I want to thank you both for taking time to be with us today. We’re going to be watching this. And you say, Sara, with stuff from the Hubble, we should be watching for that coming out?

SARA SEAGER: We should be watching for it. But remember, we’re not sure what nature has in store. We might just not see anything because Hubble can only look at a very narrow waveband. And it’s not the most appropriate or powerful tool for these planets.

IRA FLATOW: But it’s already making observations at this point.

SARA SEAGER: It is. It’s already making up– in fact, it already observed two of the TRAPPIST planets a few months earlier.

IRA FLATOW: So somebody knows and is not saying–

SARA SEAGER: That particular one was published, and they didn’t see anything there. But we’ll stay tuned.

IRA FLATOW: That’s our motto here. Thank you, Dr. Seager. Sara Seager, professor of planetary science and physics at MIT. Laura Trouille, director of citizen science and co-investigator for Zooniverse at the Adler Planetarium.

And you can find links to Zooniverse citizen science projects on our website at sciencefriday.com/exoplanets. And while you’re there, check out our Spotlight on the search for life beyond Earth. You can find related articles and videos and more at sciencefriday.com/lifebeyond.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.