Stories From Those On The Frontlines Of Sea Level Rise

19:35 minutes

This segment is the last in our Fall Book Club series about Elizabeth Rush’s book, Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. For more conversations from this series, visit our Book Club landing page.

Next week marks the start of the UN’s annual conference on climate change in Glasgow, Scotland. It’s a big moment for global consensus on climate change: Nations are supposed to make new, aggressive pledges to lower their emissions in the attempt to prevent the planet from hitting 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming.

Meanwhile, in the world we see and touch, seas are already rising. In some coastal areas, seas have risen between 0.5 to 1.5 feet in the last century. We’re also already seeing hurricanes with higher storm surge, and heavier rainfall. More change, of course, is projected. (Check out NOAA’s tool for tracking how your area might be affected under different sea level rise scenarios).

The SciFri Book Club has been talking about these risks, and reading about how these numbers have endangered wetlands, flooded homes, lost livelihoods, and sometimes scattered communities in Elizabeth Rush’s 2018 book Rising: Dispatches From The New American Shore. But while we’ve talked to wetland scientists and Elizabeth herself, the voices of community members most affected by climate change—a key part of Rising’s mission—were still missing.

In a final conversation with guest host Sophie Bushwick, producer Christie Taylor shares some of the stories of people on the frontlines, including a real-estate agent who helped his neighbors relocate after Hurricane Sandy, and the leader of the Gullah Geechee people on the sea islands of the southeast coast. Plus, social scientist A.R. Siders’ insights into communities’ need to adapt to sea level rise, and how they can be most successful.

Harriet Festing, Anthropocene Alliance, a coalition of grassroots organizations across the United States centered on climate and environmental justice

We’ll be working with one member where residents are flooding, they’re attending city hall meetings, they might have a Facebook group, they don’t really know what to do next. And we’ll start to match them with the government agencies, the nonprofits, the granting opportunities, to start to both better understand their risks, develop a suite of solutions, and then actually implement those solutions.

And so that’s not just about…the challenges of a FEMA grant getting to community, but it’s also about the challenges of a FEMA grant with a HUD grant with a USDA grant with Army Corps of Engineers technical assistance. Being able to be coordinated in a way that works and supports a community versus just overwhelms them.

And all of us, our job is to make sure that we’re serving the needs of that community leader. And then the scientists will work in supporting them.

June Farmer, Marin City People’s Plan, Marin City, California:

The problem that we have is that we have too many people on the outside. They come in and tell us exactly what we need instead of letting who lives there tell you what’s happening, and what we need. A few years ago, they did an assessment of Marin City. Not one person in Marin City was interviewed. Not one person in Marin City was talked to, but they spent $350,000 on this assessment and wrote a 700-and-some page report. Who’s going to read it? Yeah, so what we need is people to rally behind the people in Marin City, and to help us come up with solutions.

When you have engineers, and people with degrees [who] come in, they think they know more than what the community people know. We need money, we need people, we need supplies. We need people to listen.

Gloria Horning, Higher Ground Pensacola, Pensacola, Florida

They want to put 20-story high rises on this park, which is right at the bay. In our community, our roads [already] flood at high tide. Okay, so where’s all that water gonna go when besides stormwater, we got high tide coming in. And then you’d have Washerwoman’s Creek coming up. So nothing can go anywhere. And so we flood. Now our homes don’t necessarily flood but we can’t get to our car. And your car better be at higher ground because it’s going to get flooded.

Susan Liley, Citizens’ Committee for Flood Relief, De Soto, Missouri:

I’m the flood lady, is what they call me. If somebody is going to build a house or buy a house, I get calls and [they] say, ‘Hey, do you have pictures of my house, does it flood?’ And if I tell them, or show them a picture, ‘Yes, it did,’ they still buy the houses. So it’s just it’s very frustrating.

Sometimes I think it’s getting better, because we have some wonderful partners that we work with. But the legislators [are] the ones that really could help. And they haven’t. They’ve just sat back. They could be heroes. When I went to Washington, DC, I went in to see our congressman. It was Jason Smith. And he said, ‘Why haven’t you helped yourself?’ And I’ve pondered on that question for so long. How do you help yourselves other than apply for grants and stuff? And I’m an old grandma trying to figure out how to apply for these grants and things. Without our partners…[we] would be lost.

Rebecca Jim, LEAD Agency, Tar Creek watershed, Northeast Oklahoma

This water coming down Tar Creek is a regular creek. But partway down it comes through several miles—passes through several miles of contaminated chat from mine workings. From one of the largest lead and zinc mines in the country, actually in the world. It’s an abandoned mine site. There’s no more mining going on. But the residue, these mountains of chat are along the stream bed. So when there is a flood event, more of that material gets wet, and more of that material will either leach in or even be carried downstream.

The Neosho River is the boundary of the Cherokee Nation. But on the other side of the boundary are nine other tribes that federally recognized tribes that got slivers of land when they were relocated to Union territory. And this creek runs through three of those tribal boundaries and impacts many of the others coming downstream as well as the Cherokees. So we believe that, as Native people we will always see water as life. And we want to recognize that again.

Queen Quet, Gullah/Geechee Sea Island Coalition, St. Helena, South Carolina

We literally live in the Atlantic Ocean. We are literally the front shoreline of what people are describing as climate impacts. But we have been here since the [1500s] and the 1600s. And we live communally on the sea islands. When you talk about something impacting in any way, it doesn’t just impact the same. It impacts our souls as a collective group as Gullah Geechee is. And so our community still lives on the water, we still live from the land, we are agrarian. And we harvest both from that land and from the sea. So of course, it’s important to us that we can continue to do that and thrive for hundreds and hundreds of more years.

And if you’re going to buy anybody out then buyout the resorts, buyout the people who moved here last, and then invest in the communities that were here for the hundreds of years. Don’t ask us to move, because we didn’t create the problem.

Joe Tirone, Staten Island, New York

They had a meeting. And at the very end, they said is this guy, Joe Tirone, he’s an investor, he wants to tell us about a program he learned about the government. So I got to explain the program. And then I said, How many people here would be interested? There’s about 200 people in the auditorium. And again, part of the miracle was the the gathering place was St. Charles Church. And it was the only place that hadn’t lost electricity. Like on that whole block. They found it, they met there. Even their microphones worked. And everybody raised their hand, a sea of hands, I was not prepared for that. Neither was anyone who was in the auditorium prepared for that. But I would say that [Hurricane] Isaac was like, the first punch. And then then [Hurricane] Irene knocked them all back on the heels. And then when [Superstorm] Sandy came along, that was a knockout punch, they had had it.

Terri Straka, Rosewood Strong, Socastee, South Carolina

Essentially I’ve had to rebuild my house twice. It’s extremely stressful emotionally. There’s a lot of anxiety. And and, you know, I think we also suffer a lot of trauma. And so you are stronger as far as you know, adapting and having to deal with this, but still emotionally, it takes a big toll on you.

Economically, we’ve all been ripped to the bone, pretty much, because initially, we were able to take out loans, or refinance our houses, you know, and then we reinvested most of the money back into the homes, because we never thought it was going to happen again. And so that money got wasted. And even if you did have insurance, you know, there’s a lot of variables that even insurance doesn’t cover.

A.R. Siders is an assistant professor in the Biden School of Public Policy and Administration at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This is Science Friday. I’m Sophie Bushwick. Ira is away this week. Next week, marks the start of the UN’s Annual Conference on Climate Change in Glasgow, Scotland. It’s a big year for Global consensus on climate change. Nations are supposed to make new aggressive pledges to lower their emissions in the attempt to prevent the planet from hitting 1.5 degrees of warming. Meanwhile, in the world we see and touch, where you live maybe seas are rising. And with them, climate change is bringing hurricanes with higher storm surge and heavier rainfall.

Depending on where along the coast you are, seas have risen between half a foot to a foot and a half in the last century. And more, of course, is projected. The SciFri Book Club has been reading about how these numbers translate into endangered wetlands, flooded homes, lost livelihoods, and sometimes scattered communities in Elizabeth Rush’s 2018 book Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore. And here to talk more about some last reflections from this journey is SciFri producer, Christie Taylor. Hi, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Hey, Sophie.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So what are we talking about today?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Well, Sophie, we have talked a lot about the loss and threat of rising seas already. But as Elizabeth herself has told us, Rising as a book is really about how communities are beginning to recognize what’s at stake and working to protect what they feel is most important along the way. Here she is kind of unpacking that for us.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– think there’s a series of really important lessons to be learned around how a single person becomes part of a collective that can advocate for real change. I think that we see climate change as producing really interesting solidarities amongst front line communities. Amongst neighbors who might not otherwise have a reason to like fight for something together.

[END PLAYBACK]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I think this makes me want to know more about what specifically these communities can do, or what they’re trying to do when they’re building this solidarity.

CHRISTE TAYLOR: Yeah, absolutely. In a lot of places, what that looks like is leaving their homes honestly. Ideally in a planned out intentional process assisted by buyouts of flooded homes. This is called managed retreat. We’ve talked about managed retreat on the show before, but it’s actually pretty dicey. You’re more likely to get a good deal if you’re not already poor, for example. And better off communities are more likely to be able to stay together after they move. Also, not everyone wants to leave. And absolutely no one wants to be told to leave.

But as Elizabeth writes in her book too, there have been whole neighborhoods asking the government to buy their homes so they can have the money to move somewhere else.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– I think it’s absolutely imperative that we start having a larger public conversation around not only what is managed retreat, and where are people leaving behind, but where are they going to go. The place that we help people move to and thinking about the dynamics of that move is as important as thinking about the places that they’re leaving behind. I will also say that in places that I’ve seen move, there’s often still folks who go out and visit on the weekends. It’s not like the place that they leave behind disappears. I think the lines are a lot more blurry.

[END PLAYBACK]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s such a good point. As much as I’ve heard the phrase, managed retreat, in the last few years I don’t know that there’s much focus on what happens after people leave.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Exactly. And one last thing. One very small inconsequential thing. You know those bills that are stuck in Congress right now that are full of measures to actually do something about climate change?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: The infrastructure bill and then that big budget bill that’s supposed to go with it.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Right. The ones that maybe are not looking so great right now. So one of the things in the infrastructure bill is tons of money for what gets filed under this thing called resilience. Money for the Army Corps of Engineers to build drainage projects. Money for moving flood prone highways and drinking water infrastructure. Money for the Bureau of Indian Affairs to focus specifically on vulnerable Indigenous communities. But it also felt like one of the questions that the money in that bill begs for me is, what do people in the front line communities themselves actually want or need? Whether they’re going or trying desperately to stay.

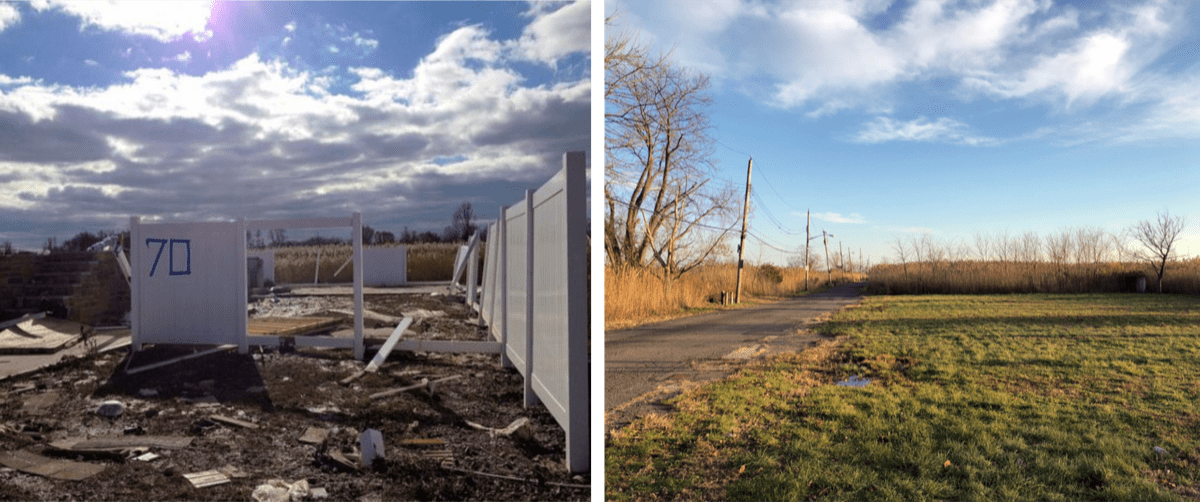

So here’s one really dramatic example of that. People on Staten Island whose homes were flooded out by Hurricane Sandy after several other storms in years prior, these people teamed up to demand that the state of New York buy their homes from them and return them to marshland so that they could relocate.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This sounds like an epic kind of story.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I mean, in some ways it was. I started by talking to someone from the Staten Island community who was directly part of this story. And his name was Joe Tyrone. He’s a real estate agent by profession. But he was also one of the big organizers of the biopush on Oakwood Beach– this community in Staten Island. The city wasn’t interested. And so Joe and his neighbors had to go to the governor for help. And even then Joe calls it the miracle buyout. Here he is describing the meeting where they first started organizing while electricity was itself still mostly out in Sandy’s aftermath.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– And then I said, how many people here would be interested? It was about 200 people in the auditorium. And everybody raised their hand. A sea of hands. It was like I was not prepared for that. Neither was anyone who was in the auditorium prepared for that. But I would say that Isaac was like the first punch, and then Irene knocked them all back on their heels. And then when Sandy came along, that was a knockout punch. They had had it.

[END PLAYBACK]

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Now Joe and his co organizers did not actually know how to do a federal buyout innately. They leaned on expertise from people who were already themselves expert. Emergency managers in upstate New York and Nashville, Tennessee. And Joe’s real estate knowledge was actually super helpful. He did a lot of pro bono work making sure neighbors were able to buy new houses with the guarantees that they were getting from the buyout program. Actually finding new homes and moving. And by the way, most of these people who took buyouts ended up staying in Staten Island nearby.

And the last factor that probably helped was that then Andrew Cuomo, at least as far as Joe saw it, was ready to be a little competitive in trying to make that buyout much faster than the FEMA average of five years. Which at 13 months, the Staten Island buyout was certainly very fast.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Wow, that sounds as Joe put it like a miracle buyout in a lot of ways.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, it really sounded like a lot lined up in just the right way. I also asked Joe what his advice would be for other communities in the absence of his specialized expertise or the ear of a competitive politician.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK] – Communities have to identify people that do have trust within the community. Long time residents preferably that says this is really good for the community. And then go around exactly the way we did. We did by knocking on doors. If you remain organized, and you remain united, and you build trust, there’s nothing that you can’t do.

[END PLAYBACK]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: What about those less miraculous buyouts?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So of people I talked to, only one other person really had a success story for getting bought out at this point. And her name is Terry Straka. She’s in a neighborhood called Rosewood in Socastee, South Carolina, which is right by Myrtle Beach. And it gets floodwaters both from the Intracoastal Waterway and a nearby river. Terry has been advocating for the neighborhood since they first started getting repeat floods about five or six years ago. And she and another resident basically used a Facebook group.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– Neither one of us were activists of any sort prior. We just knew right from wrong. And we knew what the needs were. And they were being unmet. As we started digging, and learning, and educating ourselves, we were learning well, hey, there’s this program here. Or there’s that program there. Why are we not getting this? That’s when we started going to the council meetings and getting more politically involved.

[END PLAYBACK]

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: But while the buyout was itself a successful result of her own activism, Terry is actually not sure she’ll be getting enough money to buy a new place in the current market. So she’s actually in the process of trying to get money to raise her home instead. And she’s working on getting water gauges and an effective flood warning system for those who don’t end up moving.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Does everyone you talk to who lives in places with recurring floods want to leave?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Definitely not. Many of them just want better water diverting architecture. Some are working to get grant funding for things like bioswells. And there’s one group I talked to that absolutely 100% does not want to leave and that’s the Gullah Geechee people on the Southeast coast of the United States. They’re on this narrow ribbon of coastal land and islands from North Carolina to Florida. And the Gullah Geechee people are the descendants of enslaved West Africans. They were taken to plantations on the coastal plain and sea islands. And they’re still there. And they’ve retained both a distinct culture and language. Here’s Queen Quet, who’s been chieftess of the Gullah Geechee since 2001.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– We have been here since the 1500s and the 1600s. When you talk about something impacting in any way, it impacts our souls as a collective group as Gullah Geechees. And so our community still lives from the water. We still live from the land. So of course it’s important to us that we can continue to do that, and thrive for hundreds and hundreds or more years.

[END PLAYBACK]

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Queen Quet called me in the middle of a torrential rain to tell me how big king tides, storm damage, and those big, big rains are making it harder for people on sea islands like Saint Helena, which is where she was, to grow the food they rely on, safely navigate their roads, and weather the wind damage from hurricanes.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: If they don’t want to leave their land, what options do they see for staying?

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Mostly money for adaptation. For fixing roads and raising houses. Or even pro bono labor to raise those buildings, which Queen Quet points to especially because there are so many resorts, and vacation homes, and upscale developments along the Gullah Geechees historic home.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– If it is technical assistance you want to give us, then you have the companies that do that for the uber rich people. They can pay for that. We can not pay for that. Buy out the resorts. Buy out the people who moved here last. And then invest in the communities that were here for the hundreds of years first. OK. Don’t ask us to move because we didn’t create the problem.

[END PLAYBACK]

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I think another really important point is that people on the front lines need support in choosing what’s best for them. Not just scientific expertise, but also expertise that’s just in service to their needs. I talked to June Farmer in Marin City, California. It’s been a majority Black community since World War II. And they’re inland enough to not get flooding directly from the sea. But they do get flooding from intense rainfalls. And rising groundwater levels are not helping. So water pools up very high in people’s yards, and also in the only road in and out of Marin City.

June also told me a story about one of those rains and having to help a young boy find a safe way to get through the flood waters. His options were basically to wade through really deep water or walk along the freeway entrance. And while June’s work with the Marin City people’s plan has netted them grants for building green infrastructure, which is what they want for diverting rainfall so it’s less dangerous, June says it’s been a struggle to be heard by the very people with the money to make a difference.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– We have too many people on the outside that come in and tell us exactly what we need. A few years ago, they did an assessment of Marin City. Not one person in Marin City was interviewed. Not one person in the city was talked to. But they spent $350,000 on this assessment. We need money. We need people. We need supplies. We need people to listen.

[END PLAYBACK]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That sounds so frustrating.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, doesn’t it? And June was one of several people to express this frustration at me. Of knowing exactly what you need, of having a plan, and then just never being given the money to make that plan a reality.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: We’re going to pause to take a short break. And when we come back, we’re going to pull it all together with help from a sociologist. This is Science Friday. I’m Sophie Bushwick. Our fall book club has been reading Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore with author Elizabeth Rush. And on top of conversations about marshes, sea level rise, and resilience, we also wanted to talk about communities. How they respond to the risk of flooding from sea level rise. And what they feel like their options are for staying or leaving flooding neighborhoods.

I’ve been talking to producer Christie Taylor about her interviews with residents of frontline communities. And Christie, you also took some time with someone who studies these questions.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Right. So we’ve been talking about what communities want and need when facing rising seas. Whether that’s help staying or help leaving. And to help me pull all of this together, I reached out to A.R. Siders at the University of Delaware. She studies climate adaptation as a sociologist. She talks to people about the decision to stay or go. And to people who are in charge of emergencies about how they’re wrangling the challenges of climate change.

Spoiler alert. She’s also someone who thinks that some amount of planned intentional retreat is going to be necessary as climate change makes more of the coast into a floodplain. But she also thinks there’s a way for people who don’t want to leave to stay in some ways. As long as they’re given the resources to make the choice that works best for them.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That sounds a lot like what the other people we heard from were saying about being listened to, and given money to make the changes they want.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Exactly. What the community wants is a super important part of the story. And here’s my conversation with Siders.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– The general categories we talk about when we think about adaptation, especially in a coastal or in a flood prone area, the general categories are retreat. So relocating away from the hazardous area. Or avoidance. Don’t build there in the first place. But then we have resistance. So in the flood context, this is things like flood walls, or sea walls, or beach nourishment, building dunes, maybe putting living shorelines. Anything that prevents the water from getting to you.

And then there’s accommodation. And this is things where you let the risk happen, but you reduce the harm it causes. So imagine elevating your homes so the water comes and the water goes. And yeah, it still causes some health concerns and maybe it hurts your car. But you yourself are safe, and your house is safer. So it reduces the damage.

– Well, and that brings me to a question about people who do want to stay where they are. Are they going to get the adaptation help they need to stay in place? Is there a way to stay in place if you really value your community being in that place?

– I really want the answer to be, yes. But most decisions about adaptation resources and like other types of resources in the United States are based on property value. So we build million floodwalls in front of million homes. We don’t build them in front of lower income housing even though it might protect more people because the property is not worth as much.

There’s a great study by Eric Tate in Iowa looking at Cedar Rapids, Iowa at the decision to build a flood wall on one side of the river that would protect more expensive properties. And not to build a flood wall on the other side of town where there was less expensive property because it’s not cost effective. And that’s a real equity issue. Right. And I think this is a huge problem.

Unfortunately, in the United States, we are making our decisions based too much on property value and not enough on people. And we need to change the way we make these decisions to think about what’s worth fighting for? What’s worth preserving? And what’s worth preserving isn’t about who has the most expensive buildings. It should be about things like who has the clearest connection to the land? Who has the greatest need to remain where they are? Who has experienced historical injustices? And that’s not the way we’re currently making decisions.

I think there is a starting to be a recognition that we need to make decisions based on that. And that people are trying to make these differently. Changing the way we make decisions is a slow process. And like everything else with climate change, the question is can we change that quickly enough to help address the suffering that otherwise we will experience? Agency participation is incredibly important. Right? At the end of the day, all of these projects should be about trying to give people options. And real meaningful options. As many as we can.

Climate change– we’ve already taken a lot of options off the table by not taking action on climate change earlier. The effects of climate change are already happening that they’ve already limited the options available to some communities. But we should be doing as much as we can to give communities all the options that they could have to try to deal with the effects of climate change in a way that helps them pursue what it is they care about the most.

– Let’s talk about the next 10 years. Regardless of political decisions at the top, what do you think we’re going to see in terms of community needs at the very least?

– All around the United States, and globally too, but especially in the United States I think we’re seeing people start to have a reckoning with just how expensive adaptation is going to be. How expensive climate change is going to be. Dealing with the effects of climate change. We’re starting to see billion dollar price tags come out of even small communities in terms of elevating roads, or maintaining homes, or elevating homes. We see tens of billions of dollars, hundreds of billions of dollars, to put flood walls around major cities.

We’re seeing astronomical price tags when we start looking at drought, and wildfire, and heat issues. And so over the next 10 years, I think those price tags are going to become higher. And we’re going to become faced with some really tough choices. There’s going to be really difficult choices in our future. And I think the thing that I hope is that we make those choices in a way that doesn’t continue to give the most of the people who have the most, and the least to the people who have the least. I hope that we make those decisions to the best we can to give people options.

– Thank you so much for joining me. Dr. A.R. Siders is a disaster researcher and assistant professor of Public Policy at the University of Delaware. She researches community adaptation to climate change.

[END PLAYBACK]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I love what she had to say about asking communities to identify what they care most about in the process of adapting. Whether that’s beach access or each other.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, me too. And while Siders kind of apologized for not having better answers to some of the questions I asked her, my biggest takeaway from talking to her was maybe no surprise communities need to have more conversations with each other about the future with the understanding that change is inevitable. And that the experts who can help communities adapt need to see themselves as in service to these communities.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Sounds like a great place to leave it Thanks, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Thank you, Sophie.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And while we ran out of time here, you can read more stories from our conversations with people on the front lines of rising seas on our website. Sciencefriday.com/adapt.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Diana Plasker is the Senior Manager of Experiences at Science Friday, where she creates live events, programs and partnerships to delight and engage audiences in the world of science.

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.