Science Seeks Snowflake Snapshots

3:57 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Ezra David Romero, appeared on Capitol Public Radio.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. A version of this story, by Ezra David Romero, appeared on Capitol Public Radio.

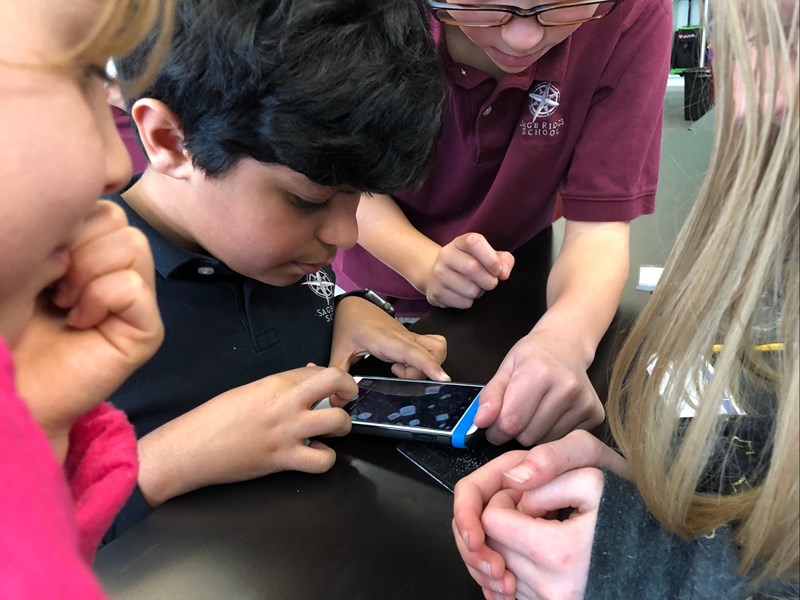

The fourth and fifth graders at Sage Ridge School in Reno fill their classroom with shouts of “ooh” and “ahh” as Meghan Collins teaches them how to take pictures of snowflakes with their phones. Since it’s not snowing, they’re practicing with salt.

“You’re going to want to get the camera really, really close to the object and then slowly move it away,” Collins explains as the students put a magnifying glass over the phone’s camera, so they can snap a detailed picture. As the kids focus the lens, they get really excited and yell, “It’s glowing.”

Collins tells the kids they are going to see many hexagons, because all snowflakes are made of them. “You can see how a simple little hexagon can turn into a complicated snow crystal,” she adds.

This is all part of a project called Stories in the Snow, organized by the Desert Research Institute in Reno. It began three years ago because scientists wanted to better understand storms, and to figure out how warmer winters alter weather systems and snow levels.

When it eventually snows, teachers will take the kids outside to catch snowflakes on black pieces of felt. They’ll snap photos, then upload them to an app called Citizen Science Lake Tahoe.

Catching a snowflake and snapping its picture is simple, but the projects lead scientists Frank McDonough says the end result may help scientists figure out everything from how severe a storm might be to how much water is in the annual snowpack — or even how climate change is affecting snow levels.

“There’s clues to be had by looking at the structure of the snowflake on the ground,” McDonough said. “Our goal is to try to get as many people collecting snowflakes over as wide an area of a storm and time periods of a storm as possible.”

The results are already being used for projects that may help improve weather forecasts, provide insights for snow removal crews, and predict when avalanches will occur.

This project is important because the other way of analyzing snowflakes is by using special aircraft, but that costs thousands of dollars per hour, says McDonough. His goal is to gather enough photos to create a database for everyone from scientists to ski resort operators.

“The snowflake’s telling you what went on in that cloud, so you can actually learn about the path the crystal took” as it fell from the sky, said McDonough.

By analyzing hundreds of photos from one storm, then many storms, scientists can get a clearer picture of how snowpack is changing in the Sierra.

“I’m interested in how these ice crystals form, how they’re growing, and which types of crystals lead to the most snowfall,” said McDonough.

He says the fun part is sorting through the images because it’s nearly impossible to find identical snowflakes.

“It is true no crystals are exactly the same because they fall through a slightly different path, they form at slightly different temperatures,” McDonough said.

Last year, students and other users submitted more than 500 photos. This year, 19 schools are on board and at least 100 kits were sent out, so McDonough expects more.

People can buy a kit — which includes a magnifying glass, a card to catch snowflakes on and a thermometer — for $25 bucks. When they do, the program will send a second kit to a school.

Heather Segale with the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center says the projects biggest impact is on students.

“They learn how to collect and analyze data, how to draw conclusions, how to communicate findings — and all of that is a great experience for the students,” Segale said. “It’s real and not just a homework assignment.”

But this process of becoming a citizen scientist isn’t just for fifth graders. Collins herself was recently hunting for snowflakes near the resort Mount Rose Ski Tahoe.

She says the best way to get a clear photo is to get as close as possible to the snowflake. “What you are seeing are a lot of crystals that have landed, and then when the snow’s laying here in the sun some of those water molecules will sublimate,” Collins said, describing the process of snow turning into water vapor.

She teaches students, but she’s also a researcher. “My dream would be to take this project beyond the Tahoe region to perhaps other states and to answer other scientific questions,” Collins said.

She wants to figure out if ash and dust from wildfires increase snowfall “or are there certain snow crystal types that are associated with avalanche frequency, or highways closures,” Collins said.

But to do that she’s going to need to even more photos of snowflakes from across the region.

For more information on how to become a citizen scientist or to order a kit click here.

Brush up on more snowflake science! Learn how to collect, preserve, and make snowflakes, create your own personal winter wonderland in a bottle, and meet the photographer who froze snowflakes in time.

Ezra David Romero is a climate reporter for KQED News in San Francisco, California.

Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is Kate Yuri.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO.

SPEAKER 1: St. Louis public radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

IRA FLATOW: These are local science stories of national significance. And whether or not your holidays had a coating of white to them, you know that predicting a winter storm, predicting it can be challenging. Researchers have a lot to learn about what goes on in the heart of a snow storm’s clouds.

And there are a couple of ways to find out. And one of them involves flying through the clouds. Another approach is trying to study the results of these storms, the snowflakes themselves. And that’s what a snowflake school project aims to do, enlist a team of students to capture and photograph snowflakes. Joining me now to talk about the project is Ezra David Romero, environment reporter at Capital Public Radio in Sacramento, California. He recently reported on the project. Welcome back.

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: Hey. Thanks for having me again.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us the point of this project.

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: Well, the whole idea is that when an airplane goes up into the clouds, they can only get data from wherever that plane goes in that moment. But scientists at the Desert Research Institute in Reno want to expand that.

They want data points from across the Sierra Nevada when a storm comes through so then they can get the information out to weather forecasters, and ski resorts, and places like that to give them a bit more accurate information about what the snow looks like and the trends they’re seeing.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re training kids to do this then, collect the data?

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: Yeah. Yeah. They’re at about something like between 15 and 19 schools this year. What they do is you have to have a smartphone and lots of students do. And they give you a rubber band. And in the rubber band is an embedded magnifying glass. And you put that around your phone to line up with their camera.

They give you a piece of felt on plastic. And you put that out in the snow until it’s really cold. And when it snows, snowflakes fall onto it. And then you go out and you take a picture of it. And you upload it to an app. And then the scientists take that and collect all those pictures. And so there’s students across the region doing that as well as just citizen scientists across the Tahoe region in California and Nevada.

IRA FLATOW: So what kind of data are they looking for? What data do the researchers want to get from this project?

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: They want to see what kinds of snowflakes are falling and by the type of snowflake, the way it looks, what kind of crystals have hooked up together on it can give them information about whether that storm was really wet, whether that storm was really cold, and what happened when that snowflake fell.

Basically, every snowflake that falls throughout a storm tells a story. And that story is shown by how it looks. And so they look at that snowflake and analyze that snowflake to see all that data. And when they look at that data over a region, they can get a sense of what’s going on in that storm and maybe even predict future storms or what will happen in the future in that area.

IRA FLATOW: Did you try to snap some snowflakes yourself?

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: I did. I met with a bunch of kids in Reno. And we learned how to use it on salt at first, because it wasn’t snowing. And then the researchers and I went up near the Tahoe area and got some snow ourselves and snapped some pictures. And our photos were– our snowflakes were a bit broken because it hadn’t just snowed.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, so it’s kind of tricky then. You’ve got to get the hang of it and figure out– yeah.

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: Exactly. They say the best time is to go out when it’s snowing and have the snow fall organically onto the piece of felt an then that way the snowflake won’t be broken.

IRA FLATOW: You’re imitating a very famous photographer who went out and collected snowflakes that way. Thank you, Ezra. And good luck to you on your snow hunting.

EZRA DAVID ROMERO: Hey, thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Ezra David Romero, environment reporter at Capital Public Radio in Sacramento. You can read his story about the snowflakes project on our website at sciencefriday.com.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.