Science Journalism Is Shrinking–Along With Public Trust In Science

17:01 minutes

Last year was a tough one for science journalism. National Geographic laid off all of its staff reporters, and Wired laid off 20 people. And the most recent blow came in November, when Popular Science announced it would stop publishing its magazine after a 151-year run, and laid off the majority of its staff.

Beyond talented journalists losing their jobs, many people seem to be losing trust in science in general. A recent Pew Research Center survey found that only 57% of Americans think science has a mostly positive effect on society, down considerably since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Is the waning trust in science reflected in the shrinking of science journalism?

Ira talks about the current state of science journalism with Deborah Blum, science journalist, author, publisher of Undark magazine, and director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Sabrina Imbler, author and science reporter for Defector.

Deborah Blum is a science journalist & author, the publisher of Undark magazine, and the director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Sabrina Imbler is the author of How Far the Light Reaches, and a science journalist at Defector in Brooklyn, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. 2023 was a hard year for science journalists. National Geographic laid off the last of its remaining staff reporters. Wired laid off 20 people.

And the most recent blow came a few weeks ago. Popular Science founded over 150 years ago, which we science nerds all grew up with, announced it would stop publishing its magazine and laid off the majority of its staff. And beyond talented folks losing their jobs, many people seem to be losing trust in science in general. I say that because a recent Pew survey shows that just 57% of Americans think science has a mostly positive effect on society. This is down considerably since the beginning of the COVID pandemic.

Is the waning trust in science reflected in the shedding of science journalism jobs? Joining me to talk about the current state of science journalism and maybe even provide a little hope for the future are my guests– Deborah Blum, science journalist, author, publisher of Undark magazine, director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT, and Sabrina Imbler, author and science reporter for Defector based in Brooklyn, New York. Both of you, welcome to Science Friday. Welcome back.

DEBORAH BLUM: Thank you. It’s great to be here.

SABRINA IMBLER: Thank you for having us.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Sabrina, let me begin with you, because you wrote about the end of popular science as we know it. We’ve seen a lot of science journalism jobs cut this year, as I say. What is the significance of this particular magazine going under?

SABRINA IMBLER: Yeah, as you mentioned, Ira, it’s been a big year for layoffs with National Geographic and Wired and shuttering of climate desks at various publications. Popular Science the website will still be around. It’s publishing podcasts and posts that feature a mixture of news and aggregate of reporting.

But the end of Popular Science the magazine, it’s a huge blow. It had just celebrated its 150-year anniversary. And the end of the magazine means an end to the kinds of long-form features, investigations, and narrative stories that made the magazine so popular for more than a century. And as long as I’ve worked in science journalism, there have been outlets popping up with an infusion of funding, and then ending when they couldn’t become profitable.

I think about BuzzFeed News, which had an amazing award-winning science desk. But I guess I had this sense that the big legacy magazines that my dad read growing up would always be around. So the end of Popular Science the magazine feels really huge.

IRA FLATOW: I grew up with that also. I feel the same way. Deborah, we have seen journalism layoffs across the board this year, as Sabrina says, and– well, for the past many years. Is science journalism more imperiled than other beats?

DEBORAH BLUM: I don’t think so. I think what we’re seeing in science journalism is reflecting the general economic struggles for journalism in general. And one of the things I’ve thought was most interesting is there was a period where journalism was really downsizing across the board. But people were bulking up their science staff.

Everyone was recognizing that climate change was lumbering toward us like some runaway monster. Everyone was dealing with the pandemic. You saw a real strengthening. And to some extent, I think what we’re seeing now is a correction.

I don’t want to call it rightsizing. But we are seeing science reporters pulled back in line with other beats at this particular time. So to me, it’s kind of a mixed signal.

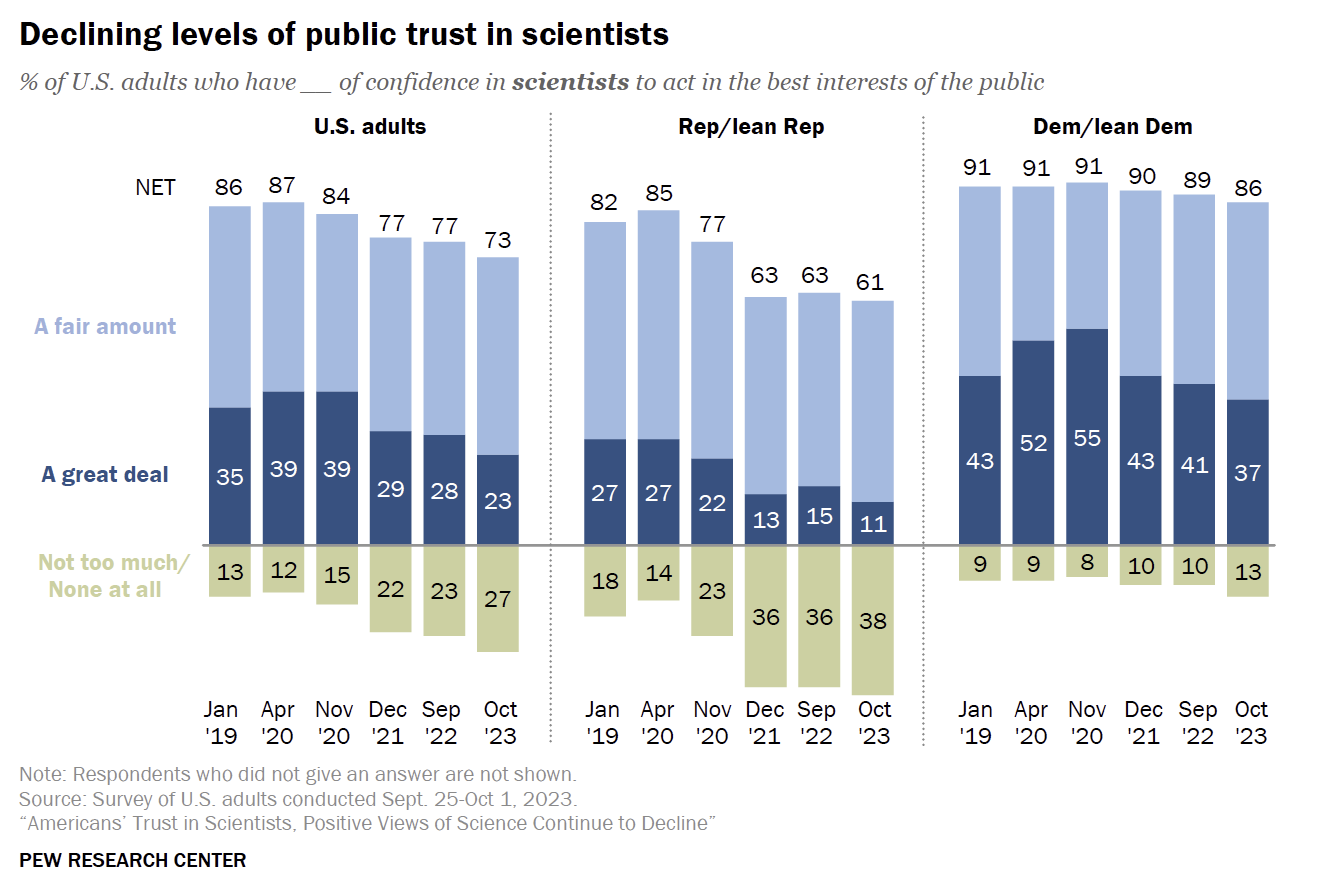

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that Pew study I mentioned also shows a partisan split. Confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public is much lower among Republicans as compared to Democrats. Is this partisanship play how science is understood and reported on?

DEBORAH BLUM: Yes, and it’s not just Pew, but almost everyone who studies the sort of politics of faith and science finds the same thing. Dan Kahan at Yale being a classic example of that. The Edelman Trust Barometer showing a very similar breakdown, which is more of an international measure. I think you find if you really parse those numbers that faith and science and the positive good in science tends to shade left more than right in general. And that leads us into the kind of interesting political quagmire that we see for science today, I think.

IRA FLATOW: What are we losing other than the jobs of our friends and our colleagues when science desks get eliminated, outlets get shut down? Let me ask you, Sabrina, to begin.

SABRINA IMBLER: Yeah, first and foremost, we lose access to information that can help us live healthier and safer lives. I think that was made abundantly clear during the pandemic. Fewer writers and editors often mean fewer stories. And every layoff represents a loss of institutional knowledge that has helped make those stories better. I think we also lose access to stories that help expand our understanding of who science affects and who can participate in it.

At Popular Science, the layoffs affected all the full-time employees of color. And layoffs often disproportionately affect staffers of color, who are often more junior. And when you remove these voices from a newsroom, you lose the ability to tell sensitively-reported stories about marginalized groups. And we lose the kinds of deeply-reported powerful pieces that inspire people to become science journalists in the first place. I think about the journalism pieces I studied in college.

And I wonder, would these stories still be able to be funded and published somewhere today in these long and exhaustive states? What kind of publications, aside from The New Yorker, have robust fact-checking budgets these days? I wonder about that.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, that’s very interesting and a good point. Deborah, would you agree?

DEBORAH BLUM: Yes, I agreed with everything Sabrina said there. But I would add that when we lose the staff of a Wired or even a Popular Science, we’re losing the reporters who really speak to the– what I think of as the people who are already around the science campfire. People who read Wired, people who read The New Yorker, people who read Science Times and The New York Times, they already get science and why it matters, right?

It’s of equal concern to me that we see the loss of people who report on science at regional and smaller publications around the United States, that areas going– back to your Pew study, red state areas where people really need to get this information are not getting it. And so I think that ability to tell the story of science needs to be looked at in this much broader landscape of who do we trust and where do we get the news.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I agree. And these cuts are coming at a time when the COVID-19 pandemic showed just how important quality science journalism really is, right? What effect did the pandemic have on how we cover science, Deborah?

DEBORAH BLUM: That is such a good point. I don’t know if you remember, but when they would have those White House press conferences during the Trump administration, and every science journalist I know was listening to the questions asked by the more general assignment reporters and thinking, why don’t they have one science journalist in the mix? Why aren’t they asking these questions?

And so back to Sabrina’s point about the understanding of– in the terms of the pandemic, herd immunity or vaccination that you have with trained science journalists, that’s a real loss– people who understand viral spread and people who understand RNA vaccines and can report it accurately. So I think we do pay a real price for this downsizing. We’re going to have another global pandemic. Climate change is not magically disappeared just because we’re downsizing our climate desks. I think it’s a cost to all of us to see these positions disappear.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I think trust in science, as we’ve been talking about, has dropped since the beginning of COVID. I think some of that has to do with the nature of science itself, that it’s constantly evolving. It struck me that the public was getting a lesson during this period in how science really works in real time, perhaps for the first time, how science shifts what we know as the data changes. But the public had trouble dealing with the scientific method, I think, dealing with the change when it really wants clarity. What do you think about that, Sabrina?

SABRINA IMBLER: Yeah, I think a lot of science journalism sometimes focuses on discoveries or just the end result, talking about something only once it’s been totally figured out, which in science, it rarely is. But I think a lot of science journalists rose to the occasion during the pandemic to talk about the process of science, as you were saying, Ira, and how messy and shifting that landscape can be. And I thought there were some real wins in terms of how that was communicated to the public. But I also wonder if being open about how messy it can be sort of helped erode some of the public trust in scientific findings when the results were often changing.

IRA FLATOW: Deborah, do you think it’s possible to get that trust back somehow?

DEBORAH BLUM: So one of the things that I want to say about science is that I don’t believe that anyone should have blind trust in any institution. Science is a human enterprise. We need to do full justice to that. And we need to allow people to see that science is people at work trying to understand the world around them.

I actually think if the public understood that better, then they’d be less horrified when we have a, OK, wear mask, don’t wear masks, and some of the other things that came up during the pandemic, because they would understand that– not only the process, but the human process of science. So I don’t sit here and say, please trust everything about science, because I don’t think any good science journalist entirely sits on that point either. What I do think that we need to do better is make people understand how it works and give them the sort of toolkit that they can navigate this world in which science and technology are the most powerful transformative forces on the planet.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking about toolkits, Sabrina, are there new ways to tell science stories that we should be exploring?

SABRINA IMBLER: Definitely, Ira. I think one of the problems of the industry right now are a lot of the fates of these publications sort of lie in the hands of venture capital firms, like the one that ended Popular Science magazine or media conglomerates, like Disney, which oversaw the layoffs at National Geographic. And as long as these publications are in the hands of these institutions and not journalists, they’re going to optimize for profit and not for journalism.

And so models that I’m very excited about– I work for a publication called Defector, which is a worker-owned media site. And we make 95% of our revenue from subscriptions. And we all own the site together, meaning we’re very stable. We’re not in danger of being purchased by a venture capital firm. Working at Defector has been a life-changing experience.

I have stability. My colleagues and I do not fear our bosses. And together, we can define the work that we want to do and create the conditions that we need to make that work happen. So if that’s time and support to write long-reported features, that’s what we give ourselves. And unlike more traditional newsrooms, Defector also allows me to be my whole self, and be open about my beliefs, and how they affect how I see the world.

And there are some other exciting models in science journalism right now. I’m thinking about The Sick Times, which is a newsletter founded by Betsy Ladyzhets and Miles Griffis, which is devoted to chronicling the long COVID crisis and sort of sets itself up in opposition to more mainstream coverage that seeks to minimize the experience of people who suffer diseases after COVID-19 infection. The Sick Times aims to be reader-funded.

I also think about The Xylom, which was founded by journalist Alex Ip, it’s a nonprofit Gen-Z science newsroom. I think about 404 Media, which is a new media company created and owned by a group of technology journalists. I think these models are popping up everywhere as people understand there sort of needs to be another way to tell science journalism stories.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting that you bring up Defector, where you work, because is it not mainly a sports journalism outfit and you’re the only science writer on the staff? But that’s how you might bring science to people who might not be seeking out science news, right?

SABRINA IMBLER: Exactly. I think it was– when they first approached me about working there, I was confused. I was like, why would you want someone writing about animals and natural history? But it’s been a wonderful fit. To your point, Ira, a lot of my readers at Defector are guys who– largely men, who subscribe to the site wanting to read about hockey, or the NFL, or basketball, or baseball.

But they are interested in science. They do like reading about the discovery of a rare frog somewhere or sort of the complicated science around bringing extinct species back to life. And it’s been a huge personal challenge to write to these audiences that don’t seek out science news, but are interested in it. And it’s a great idea to have more science journalism or science journalists at site that aren’t science specific, per Deborah’s point, to bring new readers into the fold. Because I think everyone is curious about science.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. And I know, Deborah, you must see some of this when you talk to folks about the books you’ve written, right?

DEBORAH BLUM: I do. And it’s one of the things that actually– going to the subject of hope, gives me hope. Because when I go out on book tours and I talk to people who are not necessarily interested in science– in my case, they’re interested in murder, or ghosts, or poisoning–

SABRINA IMBLER: [LAUGHS]

DEBORAH BLUM: –serial killers, which is my current book. Then, I realized that there’s this whole landscape of people out there who really are fascinated by science in ways that we don’t appreciate or, actually, in some cases, know more than I do about poison, which happened to me at one particular book club.

So hard to believe, but true. But the thing is that it reminds me that people really are, in ways that we don’t always appreciate, figuring out ways that this matters in their daily lives. And that’s really what we’re trying to get at. That science matters in your daily life.

IRA FLATOW: It used to be– and we talk about this a lot on Science Friday– that science fiction was always a way as the open door to bring real science into reporting. But now, it seems there are a lot– many more ways, Sabrina.

SABRINA IMBLER: Yeah, I’m excited about maybe more places, like Defector, popping up, worker-owned models, maybe a culture website could hire a science journalist– bring in like the science of health care or the science of personal health. I’m excited by, I guess, the next generation of journalists continuing to invent new models that I haven’t even heard of, that maybe are better than the existing ones. And I’m inspired by just thinking about hope.

I’m inspired by the journalists who despite being laid off once or many times who continue to find ways to freelance or tell these science stories in whatever way possible. But I also– I think about the journalists who have prioritized their own well-being by leaving the industry for something more stable. And I’m inspired by that choice as well. And I hope that we can work to make the industry better and more stable, so that maybe some of those people can come back.

IRA FLATOW: Good way to end this conversation. I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today.

SABRINA IMBLER: Thank you so much, Ira.

DEBORAH BLUM: Thank you so much. It’s such an important issue.

IRA FLATOW: Deborah Blum, Pulitzer Prize-winning science journalist, author of The Poison Squad, publisher of Undark magazine, Director of the Knight Science Journalism Program at MIT. And Sabrina Imbler, author of How Far The Light Reaches, coming out in paperback. Sabrina is science reporter for Defector based in Brooklyn, New York.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.