Even In A Pandemic, Science Class Is In Session

17:29 minutes

Watch the full Zoom recording of the roundtable discussion and read an article about more experiences, featuring seven science educators from across the country. This story is part of Science Friday’s coverage on the novel coronavirus, the agent of the disease COVID-19. Listen to experts discuss the spread, outbreak response, and treatment.

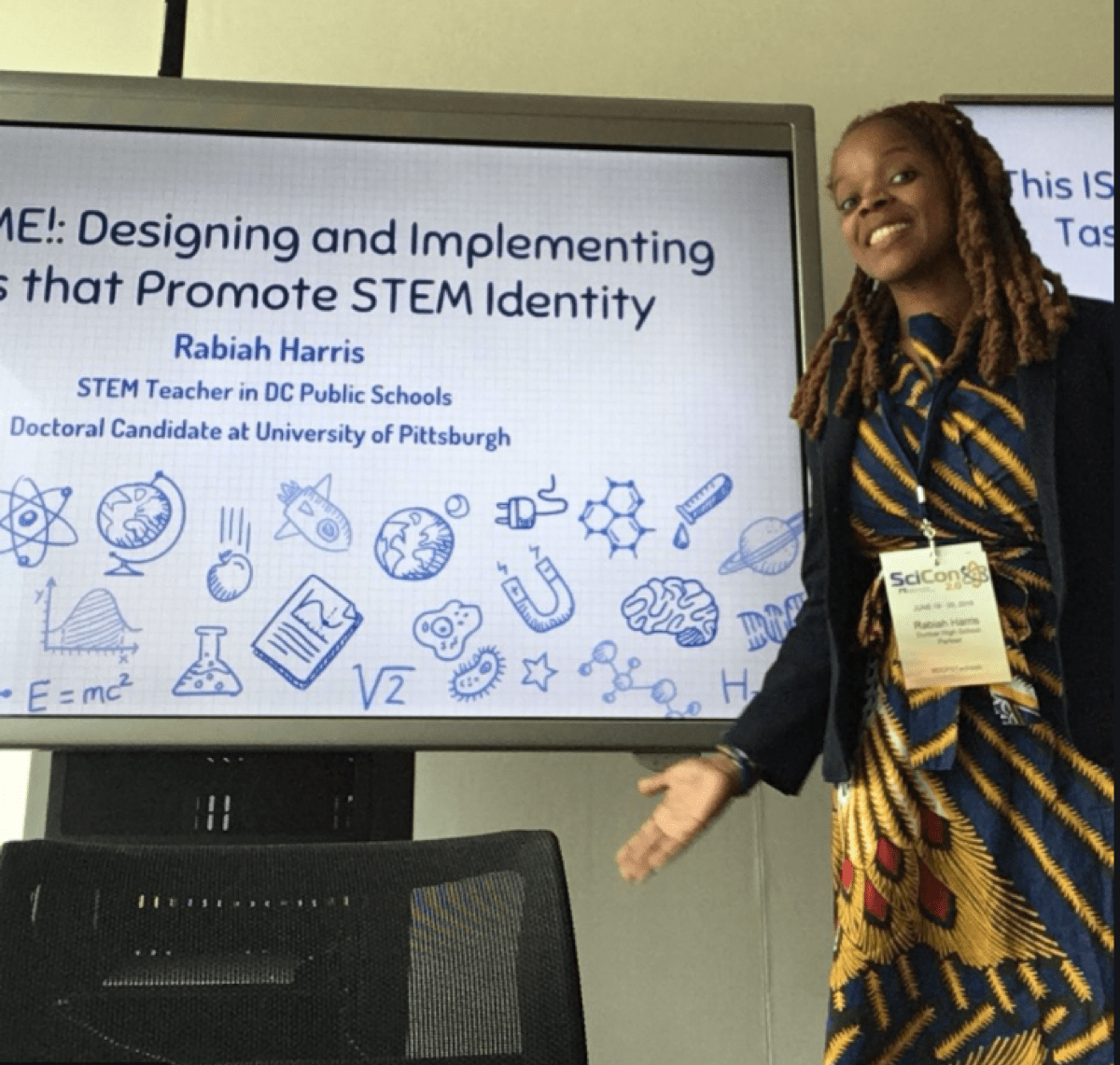

When middle school science teacher Rabiah Harris begins class, she kicks things off with an icebreaker. On Tuesday, it was asking her seventh grade students to choose between “team apple cider” and “team apple juice.” She listens and watches them as they cast votes, but their faces and waving hands are squished together on a grid on her computer screen. Since the beginning of the pandemic, Harris has been teaching online remote classes at Jefferson Middle School Academy in southwest Washington, D.C.

“We’ve been fully virtual since March, and I don’t know what’s going to happen next,” Harris says.

This academic year, school campuses across the United States look very different. Instead of crowded hallways and bustling classrooms, students are spaced six feet apart, sometimes behind plastic barriers, while others are at home on camera in a video call. Since some states do not weigh in on school operations, communities witnessed a myriad of learning approaches, such as fully virtual, fully in-person, or a mixture of both. All are subject to change as COVID-19 rates fluctuate throughout regions. For instance, on October 1, all New York City public schools reopened and shifted 500,000 students to in-person class. Meanwhile, on Wednesday, October 21, Boston Public Schools announced that it suspended all in-person learning as numbers of COVID-19 cases rose in the region.

“There have been many challenges in my 37 years in the classroom, and this one has been the greatest without a doubt,” says Rick Erickson, a chemistry and physics teacher at Bayfield High School in northern Wisconsin, a region where COVID-19 cases are currently spiking. His school is currently remote learning, too.

“The pandemic has without question had a serious impact on education across the world,” Erickson says.

Teachers, students, parents, caregivers, and staff have all felt the stress and uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic. The situation is academically, mentally, and emotionally overwhelming. While the pandemic has presented many challenges in learning, STEAM educators are adapting. They are coming up with creative solutions to continue to meet the needs of all students, like holding outdoor biology classes, dissecting flowers at home, and even delivering materials and devices to students who need them.

Harris, for instance, uses phenomena-first based learning, where students observe something in the world around them and try to make sense of it by asking questions and investigating. “I definitely thought of a phenomena initially as something that they’re actually physically doing, like looking at and doing in the classroom, but it doesn’t have to be that way,” she says. For her class’s unit on plants, she provided students take-home kits with seeds that they will grow and observe at home. “I think my biggest thing is just making sure that I don’t ever think that it’s impossible, that we can’t ever do science the way we did it before, because that’s not true.”

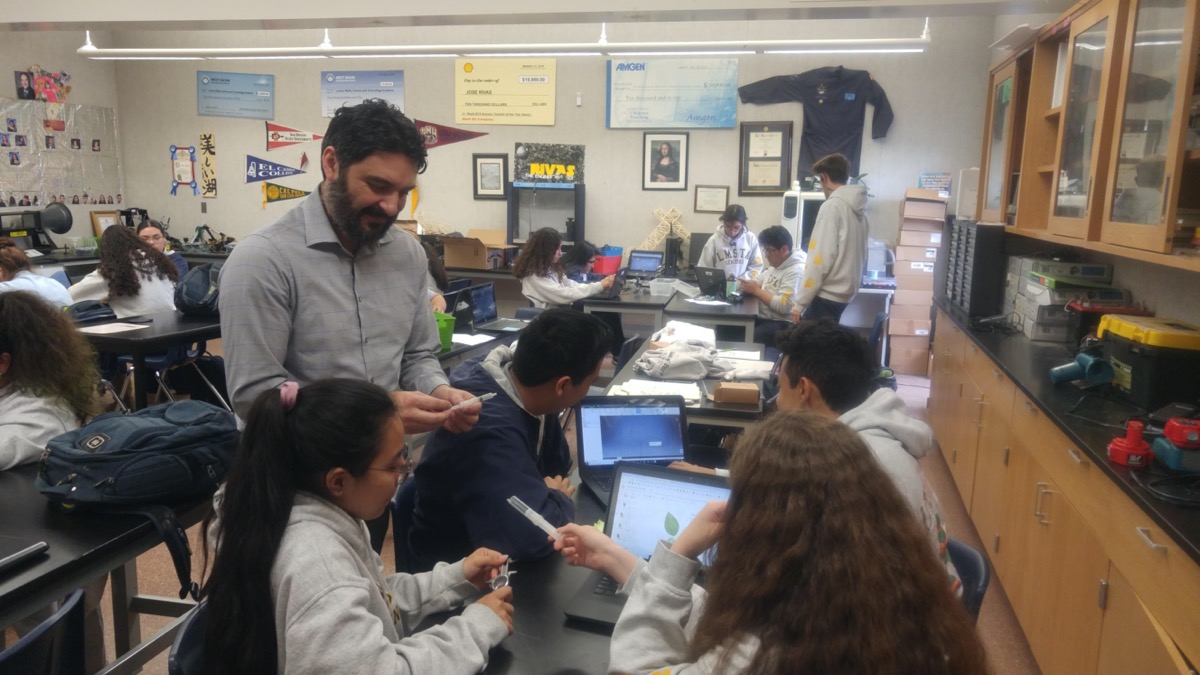

Connecting with students and understanding where they are coming from emotionally is important in educating STEM, says physics and chemistry teacher Jose Rivas. At charter school Lennox Mathematics, Science, and Technology Academy in California, Rivas uses trauma-informed teaching and social emotional learning strategies in his lessons to build community and give students choice and agency.

“One thing that always fascinated me about science and engineering, is this idea of discussion, community, and building,” says Rivas. “Trying to bring that into the virtual world is unique, and it’s possible to do.”

Flexibility has been essential during these times. You never know what a student is going through at home, says Harris. In April, Harris and her family lived in temporary housing after a fire broke out in her house. For a period of time, they were without internet. Harris knows that students have gone through similar experiences.

“My biggest thing was trying not to have too many expectations and helping my students know that I’m empathetic of whatever they might be going through, because they need to know that I care about them,” Harris says. If a student is not in the right headspace to learn, Harris works with them so that they can tackle activities at their own pace.

“At the end of the day, there is still a pandemic. I am asking them to be online, the school district has asked them to be online, but other things could be happening that are more important at the moment.”

Rabiah Harris, Josa Rivas, and Rick Erickson join Ira for a roundtable discussion on how the pandemic has impacted school this academic year. You can also watch the full Zoom conversation with more educators!

Check out a SciFri article, where you can hear from more STEM teachers and learn how they have been transforming science education under COVID-19.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Rabiah Harris is a 7th grade science teacher at Jefferson Middle School Academy in Washington, D.C..

Rick Erickson is a chemistry and physics teacher at Bayfield High School in Bayfield, Wisconsin.

Jose Rivas is an engineering and AP science teacher at the Lennox Math, Science and Technology Academy in Lennox, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Remember last spring when the pandemic first hit and schools were woefully unprepared to transition so quickly into online learning? Some teachers had only one week to prepare to teach their entire curriculum virtually, and there was frustration experienced all around. You remember that?

Well, you know teachers, they’re also students of their craft. And as this new school year began this fall, they had prepared, planned, and learned from their experiences this past spring. So what were the take home lessons from that first experience? How has the new school year been going for STEM educators?

Well, joining me now to fill us in are my guests. Jose Rivas is an Engineering and AP Science Teacher at Lennox Math, Science, and Technology Academy. That’s a charter school in LA County. Welcome to Science Friday.

JOSE RIVAS: Thank you, Ira. Nice to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Dr. Rabiah Harris is the seventh grade Science Teacher and Science Department Chair at Jefferson Middle School Academy. That’s a public school in Southwest DC. Welcome to Science Friday.

RABIAH HARRIS: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you, too. Let me begin with you, Jose. What is different about teaching this fall versus last spring, when you were thrust into this situation?

JOSE RIVAS: Well, so my classes are very hands-on, where we build stuff, we’re designing, we’re breaking things apart. So that’s been the biggest change, trying to capture that same excitement of breaking things; and putting them together; and coming up with new ideas; and using really advanced equipment. We have welders, we have 3D printers.

Right now it’s coming up with alternatives, virtual alternatives, so that the students can still get that sense, and still get some of that design work. So we’re doing a lot of design work now versus prototyping. We could do virtual prototyping. So we’re doing what we can with the resources that are available.

IRA FLATOW: Rabiah, you teach seventh grade, which is I imagine, very heavy into science. What’s different about how you’re teaching now?

RABIAH HARRIS: I would say similarly, we don’t do quite as much prototyping, as I don’t teach engineering anymore. But I used to, as Jose does. But we also did a lot of things hands-on in class, and so there has been a big adjustment.

But I think that the lessons I learned in the spring have really helped me to do better this fall, because I still have my students working in groups. I still have them doing tasks together. And I even sent them home with the materials for next quarter. So I’m really excited about them getting to do some hands-on things even though we’re apart.

IRA FLATOW: I’m glad you picked that up. Because when I picture remote learning, I imagine that instead of these students sitting in a classroom listening to their teacher for six hours, they would be just sitting in on a Zoom call like we’re doing with their classmates listening to the teacher for six hours. But that’s not what’s happening, you say.

RABIAH HARRIS: No, not in my class. So I have my students 80 minutes 2 times a week, and I see four different sets of students. So my students come in, we do a fun icebreaker, like yesterday I asked them if they are team apple cider or team apple juice. And then we got to talk about what we’ve got to do now, just as what we are doing.

But then they immediately go in to a task, where they work together, even having their own small mini calls, or just talking on a discussion board. And I sort of monitor and go around to different rooms, in a sense breakout rooms, to see them. Then, we come back together, and they get to present out, and then I do a short little thing. And then they go do some asynchronous work, and I stay on the call for students who need help.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think there is something different about teaching STEM, science, technology, engineering, math, remotely versus another subject, English, literature, whatever?

JOSE RIVAS: Oh, yeah. So the one thing that always fascinated me about science and engineering, is this idea of community and building consensus. So you collect all these data points, you create these models, you create these prototypes. And there’s discussion, and there’s community, and there’s building. And trying to bring that into the virtual world is unique.

And it’s possible to do, if you have the right relationship building, if you have the right strategies and there. So a lot of social, emotional, learning strategies, that you include in there. You also include trauma informed teaching strategies to bring the students out, and contribute, and still have that sense of community.

IRA FLATOW: Social emotional learning what does that mean?

JOSE RIVAS: Yeah, that’s a great question. So it’s about the students self-regulating both academically and emotionally, giving student choice, giving them opportunities to express their thoughts. And this is all embedded within science. And so when my students went from last school year, we had these experiences in the classroom.

So when we transferred over to distance learning we were able to keep that same dynamic, even though we were outside in our own homes. So that social emotional learning part helped them continue to monitor their emotions, and create smart goals, and continue that process.

IRA FLATOW: Rabiah, how do you keep science learning fresh and different every day? Do you find that a challenge as you teach remotely?

RABIAH HARRIS: I do sometimes, find it a challenge, but it was a challenge that I wanted to have in the classroom, too. This is my 16th year teaching. And I think that sometimes– my mom has been teaching for 52 years– so I think that you definitely can get to a point where you’re like, I’ve done this before, I can do it this way. And so in some ways, virtual helps to reinvigorate that. But that’s a challenge that I really love to have, even though it is something that I have to do, I feel really excited to do it.

IRA FLATOW: And you said you do something called, phenomena first learning. What is that and is it compatible with remote learning?

RABIAH HARRIS: I think it is. You just have to think about it differently. Students learn about the phenomena first, that helps them to really want to investigate more. So it helps them to want to be the driver of what’s going on. Like, why are those tree roots growing that way?

And I think that it can happen in a virtual space. I definitely thought of a phenomena initially as something that they’re actually physically doing, like looking at and doing in the classroom. But it doesn’t have to be that way. And I think that sometimes, for things that I did have in that way– units that did start out– like you had to physically touch something.

I might just have to think about them differently now, but it’s not impossible. And I think my biggest thing is just making sure that I don’t ever think that it’s impossible, that we can’t ever do science the way we did it before, because that’s not true.

IRA FLATOW: Can you use stuff that’s found in the house versus what you would normally find in the classroom, or have to bring in the classroom? I mean, is there sort of an advantage to some kind of projects, that you can do them at home, Rabiah?

RABIAH HARRIS: Yes, I think there definitely are. Like I said, we’re doing a human body. So right now, your body is a part of what we’re learning about. But we’re also about to do plants, so I did send them home with seeds. They just came to school to pick up seeds and soil in little pots, and they’ll get to design their own experiments, which a lot of my students haven’t had the experience doing.

One of my kids even said, I’ve never grown a plant, Miss Harris. I don’t know if this is going to work. And I was like, but the point is that we’re going to try. And that it’s OK if it doesn’t work out perfectly.

IRA FLATOW: Rabiah, did you have any expectations for how remote learning was going to go, that have changed once you were actually started doing it?

RABIAH HARRIS: I try to not have as many expectations. I knew that internet could be something. I actually had a fire at my house in April, so I ended up being in temporary housing. So I ended up not having Wi-Fi. And I know that my students have gone through similar things for lots of reasons.

So I even have an expectation that says, if you’re not in the headspace for learning today, let me know so we can work something else out. Because I think at the end of the day, there is still a pandemic. I am asking them to be online, the school district has asked them to be online, but other things could be happening– that are more important than that at the moment. And if they just let me know, I can help them work through what I’m asking of them, so that they don’t feel overburdened by this too.

IRA FLATOW: Let me turn the question about home education around and say, have you learned anything during this home stay, where the kids were at home, that you would take back to the physical classroom with you when you get back there, Jose?

JOSE RIVAS: Yeah, so it’s been interesting in terms of my engineering design classes, where before we have these hours during school time, and now I have students that will send me a Zoom invite at 7:00 PM. Hey Mr Rivas, we want to go over this design with you. Are you busy right now? We want to talk.

And that’s something that didn’t happen before. And I like that, that they’re into what they’re doing and they want to talk. And yeah definitely, if I’m available I will jump in. And that’s something that I want to take back, especially if they have homework questions, or they have project questions.

They know that I’m available, and understanding how to use Zoom, and learning the Zoom system. We have that opportunity now, to just continue the conversation, within reason, obviously. Because teachers need to break too, but it’s nice to have that additional flexibility. So I’m definitely going to take that back.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask both of you this question, that I’m sure I’ll be asking it of many teachers, and that is I’ve heard from teachers saying that they’re just getting burned out by this teaching kids at home. And I’ve heard a statistic that says maybe one in three teachers are not going to go back to school full time. What do you say to this, Rabiah?

RABIAH HARRIS: That’s definitely possible. There is a lot to think about in thinking about ways for self care, and trying to turn off, and not leaving your device on to answer questions. Because a lot in the spring I was answering emails at 11:30, phone calls at midnight, because that’s when kids are up and they were trying to get their work done. And I felt like I had to be there for them.

So I think that one of my biggest things that my friends and I talk about, is turning off; saying OK after 6:00 or 7:00 I’m done for today; taking that time on the weekends to do things for us; because I think that it can really feel– because you’re home and you’re on the same device you were on all day at school, you don’t really get that separation of traveling home. You don’t get that separation of taking a moment.

So I think that the biggest thing is working in that time. But the reality of it is, that it is a lot for a lot of teachers. And I think that school districts have to be ready for that, ready to think about the things they can do to help teachers cope in the midst of all of this.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with STEM educators about the return to remote learning. I know many schools started out fully remote at the beginning of the school year, hoping to move to a hybrid, in-person model after a few months. But with COVID cases spiking now in most states, it seems like remote learning is going to continue throughout the fall.

And one state where COVID is running rampant is Wisconsin, where over the past week there have been on average about 3,400 new cases per day, according to The New York Times. Joining now the discussion is Rick Erickson, Chemistry and Physics Teacher at Bayfield High School, in Bayfield, Wisconsin. Welcome to Science Friday.

RICK ERICKSON: Thank you, happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Rick, I know you teach in Wisconsin, one of the worst state’s experienced COVID spikes right now. What’s happened to your school’s plans to go back to school learning?

RICK ERICKSON: We had a plan in place that identifies a fully virtual model, a couple of different hybrid models, depending on how much we have to socially distance. And then hopefully at some point, a return to full face to face, which I really don’t see happening in the near future. And I think the recent spikes in Wisconsin have really challenged our thinking. Because I think what we’re starting to see– and I hear this not just in Wisconsin but in many places– we’re starting to see a lot of COVID fatigue. And so it’s happening– these spikes are happening at the time where people are also getting tired of dealing with the issue.

And so even though we were leveled off for a while, there was talk then, of going back into the hybrid model. And already there’s the question, what are the metrics that determine whether we go back or not. But there’s also the drive from home, people who want their kids in school and the challenges that are faced at home.

And so we understand those challenges. And so we started making the move to look at the hybrid model and we’re still looking at that. But now with the spike, everybody’s taking a step back and re-evaluating. And again it’s that question of, what are the bottom line metrics that determine when we moved into those phases.

IRA FLATOW: Well let me bring that up a little bit more, because I know the Indigenous communities across the US are being hit pretty heavily. Did that factor into your school’s consideration of whether to return to school this fall?

RICK ERICKSON: Absolutely. A lot of our families are multigenerational families, and so there’s higher risk in those families. And that really played a big role in our determining to go back fully virtual. We’re the only school in the area that went fully virtual at the beginning of the year. Otherwise, most schools went back either in a hybrid, or a lot of them went back five days face-to-face full time. And so that makeup of our community had played a big role in our decision to go virtual.

IRA FLATOW: That’s the Anishinaabe tribe?

RICK ERICKSON: Yes, that’s correct.

IRA FLATOW: I know you’ve been teaching for 37 years, and I’m sure you’ve had to update your materials over the years, right? But this must be totally different for you during COVID-19, to adapt your curriculum.

RICK ERICKSON: That’s a good point. And I think you’re going to hear this from most teachers. We adapt our curriculum every day and every year. I mean, that’s what keeps us invigorated. Science not only changes, but there’s so many different ways you can approach the way you teach science, and so we’re always changing.

But there is no question that this has been the biggest challenge in my career. Without a doubt, the biggest challenge is not having the kids in the classroom. And you’re going to hear this from other teachers, as well. It’s the connections with kids that matter, and it’s the relationships that you build. And doing that remotely and virtually is so much harder.

It’s not that you can’t do it, but it’s those interactions in the hallways; and the interactions when they come into your classroom; and as they walk into the building; and all those little pieces that build that relationship. And so that’s been the biggest challenge, without a doubt, is how do you bridge that in a virtual setting?

IRA FLATOW: One final question for you, Jose. What’s the one thing that’s going well for you that you’d want to share with other teachers?

JOSE RIVAS: There is a lot of things that are working. It’s been interesting interacting with the families on Zoom, since we’re doing distance learning. And it’s been interesting because I’ve had parent conferences during Zoom and I’ve had discussions with parents. And the kids get shy, as well. Well, we’ll do a breakout room, we can talk really quick.

So that’s been an interesting connection that’s been very valuable. And making those connections– even though we’re distance learning– I’ve always liked making connections with families and understanding where my students are coming from, and all the different things that they’re dealing with. And right now with everything that’s going on, I have more of an opportunity to do that, which helps with everything else that I’m doing with getting them motivated to do the different projects.

Like everyone said, we’re making kits and having them pick it up, and go to do the experiments at home. So it gives them that extra motivation and that understanding that we care as teachers. So it helps with everything else. I guess that’s the big secret, is building relationships. And by building relationships, students will gravitate to do the things that you want them to do, and learn science, and learn engineering.

IRA FLATOW: Jose Rivas is an Engineering and AP Science Teacher at Lennox Math, Science, and Technology Academy, a charter school in LA County. And Dr. Rabiah Harris is the seventh grade Science Teacher and Science Department Chair at Jefferson Middle School Academy, a public school in Southwest District of Columbia. And Rick Erikson is the Chemistry and Physics Teacher at Bayfield High School in Bayfield, Wisconsin. This segment was an excerpt from a longer Zoom conversation with even more STEM educators, and you can watch that video up on our website at sciencefriday.com/remotelearning.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Xochitl Garcia was Science Friday’s K-12 education program manager. She is a former teacher who spends her time cooking, playing board games, and designing science investigations from odds and ends she’s stockpiled in the office (and in various drawers at home).

Diana Plasker is the Senior Manager of Experiences at Science Friday, where she creates live events, programs and partnerships to delight and engage audiences in the world of science.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.