Saturn’s Rings Might Be Made From A Missing Moon

4:22 minutes

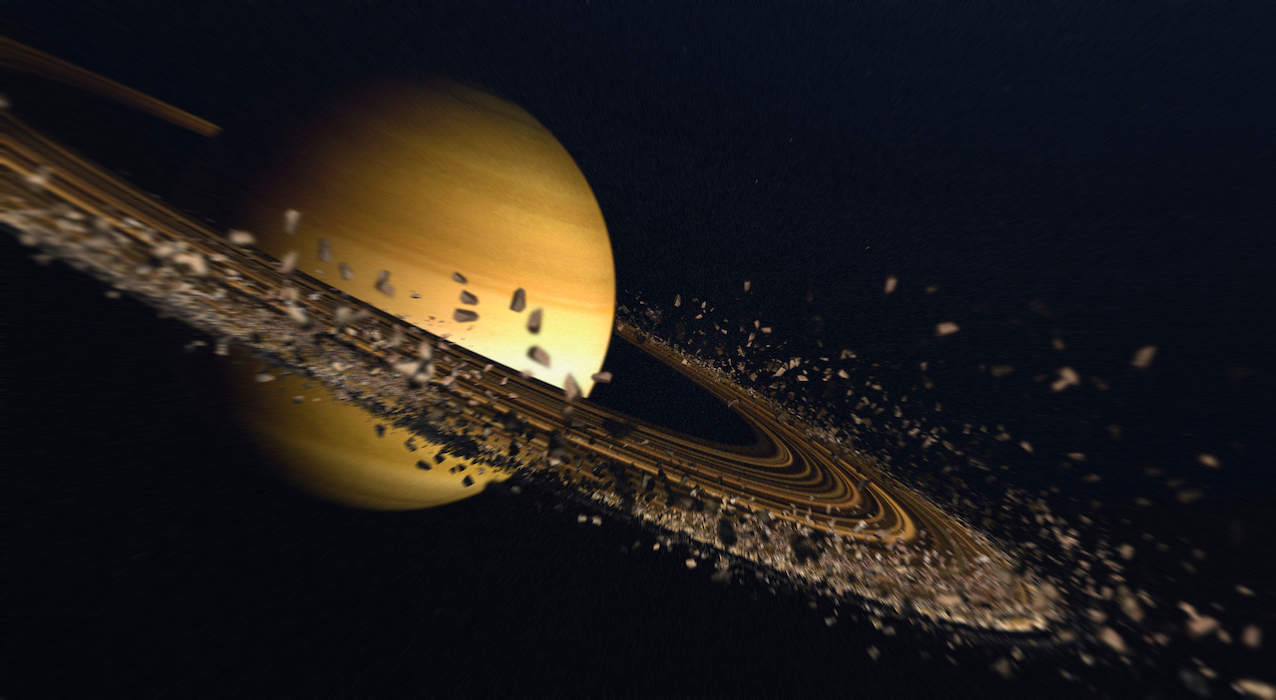

Saturn’s rings are one of the most stunning, iconic features of our solar system. But for a very long time, Saturn was a ring-less planet. Research suggests the rings are only about 100 million years old—younger than many dinosaurs. Because Saturn wasn’t born with its rings, astronomers have been scratching their heads for decades wondering how the planet’s accessories formed. A new study in the journal Science suggests a new idea about the rings’ origins—and a missing moon may hold the answers.

Co-author Dr. Burkhard Militzer, a planetary scientist and professor at UC Berkeley, joins Ira to talk about the surprising origins of Saturn’s rings.

Want to know more? Listen to this previous Science Friday episode about Saturn’s formation.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Burkhard Militzer is a professor of Earth and Planetary Science and of Astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley in Berkeley, California.

IRA FLATOW: Saturn’s rings are one of the most stunning iconic features of our solar system, but for a very long time, Saturn, believe it or not, was a ring less planet. Research suggests the rings are only about 100 million years old, younger than some earthly dinosaurs, and since Saturn wasn’t born with its rings, astronomers have been debating how they formed. And a new study in science adds a new idea about their origins. Here to tell us more is co-author of the study, Dr. Burkhard Militzer, planetary scientist and professor at UC Berkeley, based in Berkeley, California. Welcome back to Science Friday.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: It’s nice to have you. Dr. Militzer, so your team has a new idea about the rings involving an extra moon?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yes, exactly. We are proposing that the rings that we see today came about from a moon that was early on in orbit around Saturn, and then its orbit got destabilized. And at some point, it came so close to Saturn that it was sheared apart by the gravity, and it lost most of its material. Most of it ended up, actually, inside Saturn, but 1% is leftover that formed the beautiful rings that we see today.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that is really cool. I know there’s another element to your study, and that explains how Saturn has this tilt to it, 26.7 degrees, also due to the moon?

BURKHARD MILITZER: Not quite. The moon is related, but the tilt was actually what initiated the study. The tilt is puzzling because we think that all planets formed out of the nebula and they all spin in this counterclockwise direction. And a few planets don’t, and Saturn’s one of them. And it spins off, as you said, by 27 degrees. It’s tilted, and that you have to explain.

It doesn’t conform with our standard theory, and the hypothesis was that the culprit is Neptune. So Neptune can shift its orbit a little bit, and therefore, it can tilt the angular momentum, or the spin rate, of Saturn. So it’s very strange how the object like Neptune from far away can interact with the Saturn in that way, and it only works if Saturn has this property. And the calculations now actually show it needed an extra moon.

It’s like an extra handle. The moon has gravity. It’s an object to Saturn’s, as a Neptune can sort of tilt the Saturnian system if it has these moons to hold on to. And then the moon was lost, so at that moment, Neptune lost the ability. The rings were formed, but Neptune could no longer straighten out Saturn. So Saturn was left with a tilted angle, and the loss of the moon also generated these ring particles we see today.

IRA FLATOW: So yourself, two mysteries at the same time.

BURKHARD MILITZER: That’s exactly right. So our hypothesis we’re putting forward– there’s no direct evidence because nobody was there to watch it 100 million years ago. But indirectly, we’re solving two things with one theory. That’s new.

IRA FLATOW: That’s interesting. What had scientists theorized up until that point?

BURKHARD MILITZER: The canonical answer is, well, maybe it was born that way.

IRA FLATOW: Ah.

BURKHARD MILITZER: That was just because people didn’t have any idea how the rings would be formed later, and now we actually do. But the other thing, there’s a lot of– the Cassini spacecraft, like three years ago, it flew in between the rings and the planet, and it measured how heavy the rings are. And then there are arguments that take you from a ring mass to an age, and it gave us this puzzling result that the rings are really young.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

BURKHARD MILITZER: That’s puzzled everyone.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

BURKHARD MILITZER: The people who thought like four billion years old, they could not explain this surprising measurement.

IRA FLATOW: Quick quiz, how many moons does Saturn have? Quickly.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Oh, there are like 60-plus. We discovered more, many, many.

IRA FLATOW: 82, I think.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Well, if you keep looking, I’m sure there will be 200 or 300.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS]

BURKHARD MILITZER: Keep looking.

IRA FLATOW: Is that right? Keep looking up. And now’s a good time, actually, to look at Saturn, right? It was in opposition recently.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Yeah, to be honest, I’m a computer person. I don’t look at Saturn unless I teach a course. I could not answer this question.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] That’s good. But I love your working on it. Thank you for taking time to be with us today. It’s a really interesting study.

BURKHARD MILITZER: Thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Burkhard Militzer is a planetary scientist and professor at UC Berkeley based in Berkeley, California.

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.