For These Robots, Sexism Isn’t The Problem

16:59 minutes

Roboticists, like other artificial intelligence researchers, are concerned about how bias affects our relationship with machines that are supposed to help us. But what happens when the bias is not in the machine itself, but in the people trying to use it?

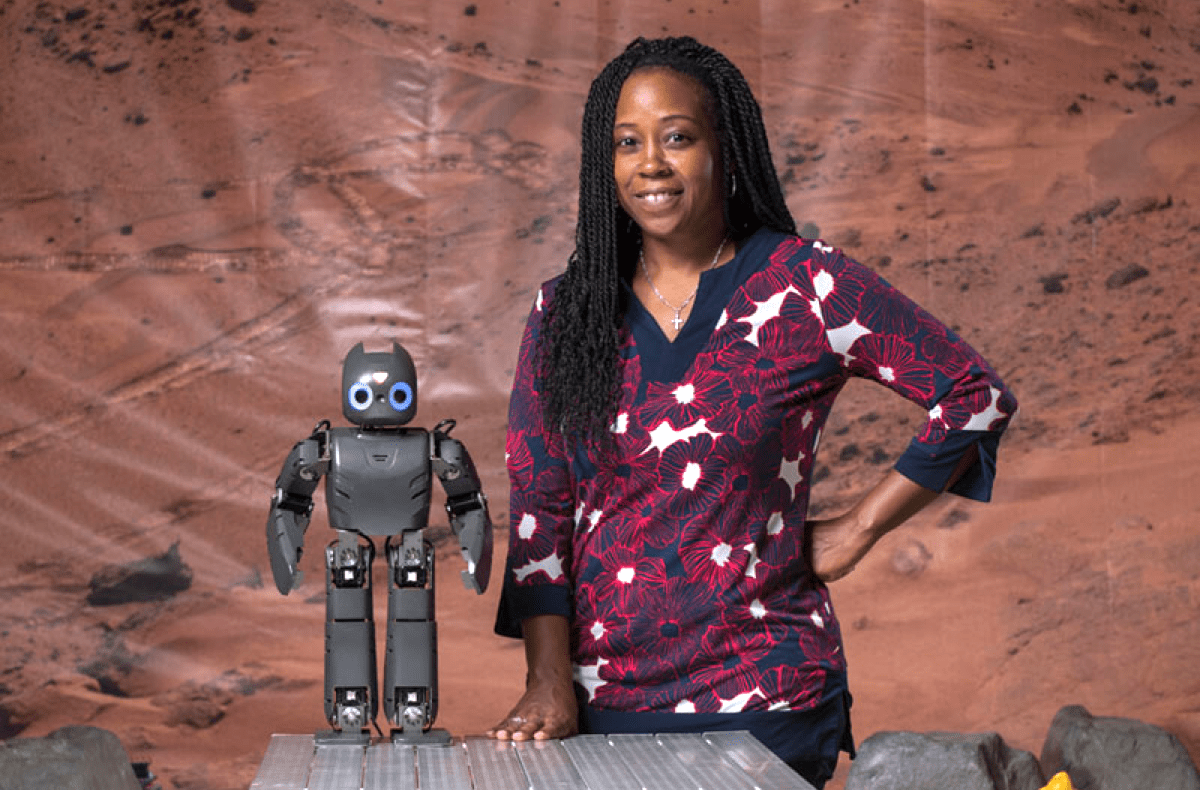

Ayanna Howard, a roboticist at Georgia Tech, went looking to see if the “gender” of a robot, whether it was a female-coded robotic assistant like Amazon’s Alexa, or a genderless surgeon robot like those currently deployed in hospitals, influenced how people responded. But what she found was something more complicated—we tend not to think of robots as competent at all, regardless of what human characteristics we assign them.

Howard joins producer Christie Taylor to talk about the surprises in her research about machines and biases, as well as how to build robots we can trust. Plus, how COVID-19 is changing our relationships with helpful robots.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Ayanna Howard is a professor and Chair of the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, Georgia.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Robots are everywhere. They listen to you speak. They help you teach. Cars with increasing self-driving capacity. There are even robots that tell jokes– I kid you not.

And of course, robots have been replacing humans in factories for decades. But as robots continue to add new jobs to their resumes, can we trust them to be competent? Producer Christie Taylor talked to a researcher about why our biases may actually be the biggest hurdle.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: We’ve talked at length on this show about how artificial intelligence algorithms often come with hidden biases, biases that make them either less useful or even downright harmful for marginalized groups like women and people of color. But what about the biases we apply to AI when we encounter it– the robots, the virtual assistants– those virtual assistants that, by the way, are almost always given women’s names and voices.

Dr. Ayanna Howard is a roboticist and chair of interactive computing at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. Last year, while investigating gender bias against robots, she found something unexpected about how we trust and relate to the robots that are increasingly helping our world run smoothly. Welcome to the show, Dr. Howard.

AYANNA HOWARD: Thank you. I’m excited about this conversation.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, me too. And I really wanted to start, actually, with some research that you published earlier this spring. You went out looking for, do people have biases against robots based on what gender they presume to be? And you found something quite different.

AYANNA HOWARD: Yes. So we know that in human-human interactions, there’s this assumption that certain jobs are predominantly filled by women versus predominately filled by guys– example, nursing is mostly female occupation, receptionists, and things like that. And so what we thought was that if robots had the same type of thing in terms of gender that you as a person would be more trusting of, say, a female robot in nursing versus a male robot in nursing and vice versa. So that was our original assumption, which we were trying to basically just grab evidence to see if this was true.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: But.

AYANNA HOWARD: Well, what we found is that in general, people don’t trust any robot. So it had nothing to do with gender and actually had to do with the robot itself. And so female robot nurse, male robot nurse, it doesn’t matter– robot nurse, no.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: [LAUGHS] And so it didn’t matter what kind of job the robot was doing, they just don’t trust them?

AYANNA HOWARD: They don’t trust– I mean, there was like maybe two occupations, but for the most part they didn’t trust– and so what we did find or discovered is that people when it comes to robots, trust is highly correlated with competency. Whereas I think in human-human interactions, we don’t have that same– like I see a nurse. I know that they can do their job. And then if they’re male or female, then it’s secondary.

Whereas here was the competency issue was primary. Like, I don’t believe that robots are competent. Therefore, I don’t trust them. Therefore, I don’t care what gender they are.

And we threw in occupations that clearly there weren’t robots. And we threw in ones that were like, oh, these are robot functions, and there’s companies making a lot of money selling robots in these spaces. One was in surveillance– a robot in the malls, a robot going around parking lots, looking for individuals and things like that. Even surveillance robots, people are like, yeah, no. No, I don’t believe that they’re competent in that space.

Surgery is another one. We have like the da Vinci system. Like, surgical robotics is a thing. And yet they’re like, yeah, no– robots, surgery, not competent.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Why do you think there’s this disconnect between what robots can do that you know they can do as a roboticist and the people you did your research with, their trust that robots can do these things that robots can do?

AYANNA HOWARD: Yeah. I honestly think it’s about media. So I said there was one or two jobs where people thought they were competent, one being delivery robot, which, by the way, we don’t have drones flying packages to us. But if you looked at the media, this is like right around the corner. We have delivery robots that are like at our doors, which isn’t a thing. But yet when you see these other roles, media always portrays them in a mistake.

So if you Google or Bing any type of surveillance robot, you’ll see these articles about robots falling into pools in the mall and kids smearing ketchup on these surveillance robots. And the robot’s like, I don’t know what to do with these kids. What am I supposed to do? And so I think it’s that, you know– like, look, these robots, they really aren’t that good because make all these mistakes. And so I really think it’s about the portrayal of them in the media.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah. Well, so going back to that question you were asking about gender, does this result that we view robots as sort of universally incompetent, does that mean that we wouldn’t react whatsoever to a robot’s gender? Or are you finding that that still has a role, just in a different way?

AYANNA HOWARD: I think it has a role in a different way. So one of the things I believe, as robots become more pervasive, which they are, I think it’s our role not to add gender. Because then we are adding in these biases, and we’re just enhancing it. So if I assume that a surgeon is going to be male and I therefore make my robot that’s doing surgery have a male gender, I’m just reinforcing these type of stereotypes, which I don’t think is good, especially since people, at the end of the day, care about the competency of the robot itself.

I honestly think that we should give people the choice. And they’re going to gender. At some point they may decide that, oh, this robot is male, and this robot is female. But I think that power should be given to the user, not to the developer.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So you’re saying that if we do gender robots, we’re actually just exacerbating our own stereotypes. What if we made all those robotic assistants male robots instead of female robots?

AYANNA HOWARD: So this is interesting. So as a developer, I can actually change the stereotype. But then I would argue we are also then not giving that power into people’s hands. Because then I can say, well, why are we gendering based on a binary construct? So now I’m excluding the fact that we don’t just have a binary gender category. And so I still think that whatever we decide, we are not doing it right. We are adding in our own stereotypes, whatever those stereotypes and biases are.

But also this is interesting, because I think it starts a conversation. As an example, if I have– we’ll use surgery, a surgery robot. And I go and I say, oh, I’m going to go see my robot. He is– someone might say, oh, your robot is a male? Well, mine is a female. Like, that starts a conversation. Then like, oh, hey, that’s true. Why did I label mine as male and yours female? I think that provides much more value about inner reflection and having conversation about biases than just a blanket every surgeon is a male that’s a robot.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Does any of this research you’ve done tell us more about how to make a robot more trustworthy in general?

AYANNA HOWARD: Yeah. So I honestly believe that robots should have the ability to talk about their mistakes. Explainable AI is a word for this. And you can look at any program. There is this uncertainty in terms of accuracy. And we know it. Before we deploy any robot system, we know how accurate it is and what scenarios. And it might be 10% inaccurate in ensuring scenarios.

I honestly think that the robot should explain what they’re doing and explain that inaccuracy such that it’s understandable to the person. I think that will enhance trust. Because then it becomes– again, it puts the power on the user to then decide, oh, OK, I know the robot said it’s almost 100% sure. OK, do I believe? And if I don’t, can I still follow the directions? I’m taking that onto myself.

So if the robot makes a mistake, I’m like, oh, yeah, but I knew it wasn’t going to be 100%. So I’m not going to blame the robot. I’m not going to blame myself.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Is that a higher standard than we would hold human beings to in needing to trust them?

AYANNA HOWARD: Yes. And I–

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: OK.

AYANNA HOWARD: –truly believe that we should hold robots to higher standards. So think about this. We, as people, we are imperfect. We each have our own lived experiences, which, again, makes us biased in multiple, multiple ways. And so why should we give them the lived experience that we ourselves are biased by? So I totally think that we should put them to a higher standard. And I think they can make us more human because of it.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: What do you mean by that? Say more.

AYANNA HOWARD: I think in a lot of times when we are called out, called to question about our own biases, a lot of times– not everyone, but most of us– do an inner reflection. Like, oh, I didn’t realize that what I said might have been sexist. Oh, why is that? I don’t understand. Let’s have a conversation. But that only happens when we’re called out about saying something. I think a robot has that ability.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: To call out biases?

AYANNA HOWARD: To call out biases. So imagine I go into a store, and I see a robot receptionist. And I go, hey, sweetie. How are you doing?

The robot’s like, hey, I’m not a sweetie. In fact, that assumes that you assume I’m a female. Why is that? Not all receptionists are female. I think you might need to think about why you thought– like you could have someone being kind of reprimanded a little bit.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: We didn’t talk about racialized robots and bias. I haven’t personally observed any robots where I’m like, that is a racialized robot. But is that something people are trying to do in any way, or is that something that we have interesting research on?

AYANNA HOWARD: Yes. And we actually had a paper that was an argument against this. But there was a paper about three years ago where a researcher had racialized a robot. He used Black and white. And what he wanted to do was test the shooter bias scenario, which, of course, ethically is like, why would you even do that?

And what they showed was that if a robot was racialized as Black, people were quicker at shooting the robot down. This actually caused quite a bit of an uproar. And when I looked at that, the researchers had primed the individuals to think about these robots as Black and white, even though in color they had skin tones of black and white. But they had also primed– like they said, what race is this robot? And then they did the shooter bias test.

And so in my group, we actually said, well, what happens if you remove this priming? People just look at it as a robot, not as a Black or white robot. They just look at it as a robot. And people looked at these robots as robots as long as you didn’t label them. Again, I believe that we as developers should not label, whether that’s with respect to gender, that’s with respect to race, ethnicity, and all of those human attributes that causes so much interesting conversations, but also harms and biases as well.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: What do you think the biggest challenges in robotics for the future really are at this point?

AYANNA HOWARD: I think one of the biggest challenges is to make sure that the robots that are created and the AI systems that are out there work for everyone and are accessible to everyone. I identify as Black. I identify as female. And I develop robots.

But my training is as a roboticist. I was trained a certain way. And so all of us really are trained in a certain way, and we’re designing for a world that doesn’t necessarily have the same kind of training. And so our solutions, they are biased even through that. Even though I may be diverse in terms of who I am, my thinking process, it still thinks through engineering, and problem solving, and things like that. That’s what I worry about, is that we don’t have enough diverse, unique voices that are designing the technology, that we might have warped the world to the thinking of how roboticists think.

I do an AI ethics class now, where I’m trying to teach AI developers how to think about some of these problems. The other thing that a lot of us are starting to do is bringing in community input from the beginning. So it’s not a– as an engineer sometimes we’ll go, I have a solution for your problem, versus working with the community to say, OK, let’s identify your problem together and develop a solution together. And that’s also another way of bringing in diverse voices.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I’m Christie Taylor. And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking about how we trust robots and how we bias against them with Dr. Ayanna Howard.

[LAUGHS] I was going to ask if you have a favorite pop culture robot.

AYANNA HOWARD: Rosie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: From The Jetsons?

AYANNA HOWARD: Rosie is my favorite. Like if you’d asked me 10 years ago, it was always Rosie, but I didn’t know why. Now I know why.

So Rosie, she was there to make life better. She was everything to everybody. She changed based on whether it was George or the kids. She had different functions. So she was adaptable.

But when you did something that she thought was wrong, she would actually call you out and hold you accountable for your human mistakes. And at the end of the day, she was social, and she was part of the family. And those are all the things I think about now in terms of robots of the future.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Another thing I think about with the future is the pandemic. Do you see the pandemic changing the role of robots in our lives or adding more of a certain kind of robot to our lives?

AYANNA HOWARD: The pandemic has definitely accelerated the adoption and use of robotics in certain types of roles. So some of those roles are in things related to cleaning and disinfecting, because you want to minimize human contact if there was an area that had some infection or prior infection. And robots are there. And there’s a whole field now that designs or thinks about PPE for robots.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Wait, what? Why does a robot need PPE?

AYANNA HOWARD: Well, because if a robot comes in contact, as we know, the virus can stay on the surface. So you don’t want the robot then transmitting it to a clean space. It’s not to protect the robot. It’s to protect everyone else. And you can’t clean it. Like you can’t necessarily clean within the joints and all of that.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: You can’t just dunk it in hand sanitizer.

AYANNA HOWARD: It’ll be very difficult to do. So the other is there’s been an increase in the use of robots for telepresence and telemedicine. And telepresence robots, I’ve seen an increase to allow a little bit more of a connection besides looking through a screen on a laptop or a tablet. Having that embodiment, even if it’s a robot embodiment that looks kind of strange, gives you a better connection to the person on the other side. There’s also been an increase in usage in AI that’s virtual as well.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I saw your TED Talk, and I really liked one of the questions that you posed in it, which was not just about us trusting robots, but can robots trust us? Why do you ask that question in the first place?

AYANNA HOWARD: So that has to do with us as humans, us as people, and as our society. Unfortunately I don’t think that robots can yet trust us. And it’s just because we are just too diverse in terms of opinions and what we want for the world. And I would say as humans, we are pretty selfish. And robots are the other. And I worry that we as people tend to treat others outside of our community pretty bad.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: You mentioned kids smearing ketchup on robots.

AYANNA HOWARD: Exactly.

[LAUGHTER]

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Well, thank you so much for joining us today. Dr. Ayanna Howard is a roboticist and chair at the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech in Atlanta. Thank you so much for joining me today.

AYANNA HOWARD: Thank you. Thank you.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: For Science Friday, I’m Christie Taylor.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.