Revealing The Ruins Below

4:26 minutes

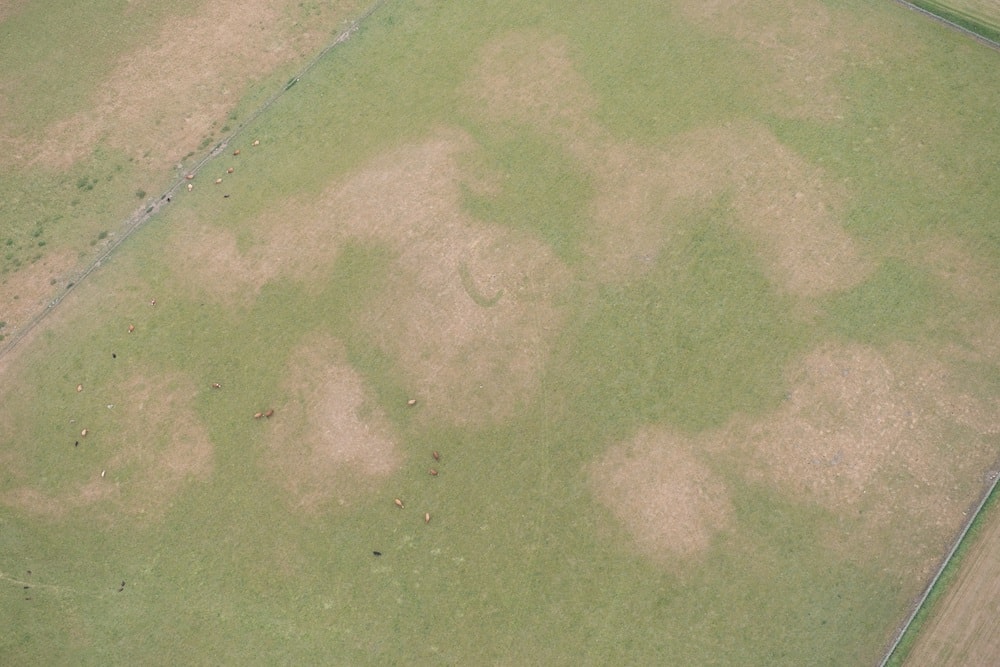

It’s been hot in the United Kingdom this summer. Numerous heat waves have rolled across the islands and the first half of the summer was the driest of that time period on record. But as lawns parch and grasses turn brown, the landscape is also revealing the buried remains of valuable archaeological finds.

[Where does the word “cell” come from? Well, it all started with a piece of cork…]

Aerial archaeologist Robert Bewley, at Oxford University, describes how “parch marks” can reveal hidden treasures.

Robert Bewley is the Director of Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa at the University of Oxford.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to play Good Thing Bad Thing. Because every story has a flip side. It’s been a hot summer all over our northern hemisphere, especially tough on countries not used to sweltering in this weather like the UK. The summer in the United Kingdom has been the driest on record. The gardens and lawns, they’ve all dried up. What could possibly be good in all of that?

Well, my next guest an aerial archeologist says it’s been a good summer for finding things buried deep beneath the ground. Dr. Robert Boulay is director of endangered archeology in the Middle East and Northern Africa at the University of Oxford in Oxford. Welcome to Science Friday.

ROBERT BOULAY: Hello. Hi.

IRA FLATOW: So this weather is actually good news for archeologists?

ROBERT BOULAY: Well, it’s good news for aerial archeologists in that we can get into airplanes, use drones, and take photographs of sites that we would otherwise not be able to see. We might get a hint of them from the ground. But you’ve got to get into the air to get the pattern of them and see these sites that, because of the exceptional weather, are showing up in grass and the various crops in a way that really only happens once every 10 or 20 years. But this has been an exceptionally dry year. So it’s fantastic news for us.

IRA FLATOW: So you mean as the ground dries out, the other stuff you can see coming up sort of visually through the ground?

ROBERT BOULAY: Yes. Yes. I mean, so particularly for parch marks, when the grass above a wall, for example, it’s obviously looking for water and nutrients. But because it’s above a wall, it can’t find them. So it just sort of dies above that wall. And therefore you get it as a yellow mark and the surrounding area is green. And then in a wheat crop or a barley crop, you get the crops above a ditch where there’s more nutrients and more water stay greener for longer. So you get a dark mark with a yellow area around it.

And we can see sites that date from 2000 or 3000 BCE or they might even just relate to the Second World War. So it’s fantastic because you get archeology from the 20th century right back to 5000 BCE. So it’s great.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re all up there flying around. Now you’re documenting these things as well as you can.

ROBERT BOULAY: Well, at the moment because it’s now August. Most of the crops are off. So that’s what the people in England, Wales, Scotland have been doing and undertaking the aerial reconnaissance. I tend to now, as you said in your introduction, work in the Middle East and North Africa. So it’s slightly different for me. But I used to do this all the time in England. And we used to pray for summers like this and hope that we would get a hot, dry summer.

And the last one everybody cast their mind back to is 1976. And we’ve had other dry summers in between but nothing on the scale of this. It’s been hotter and drier for longer than we can possibly remember.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I’ve been following that. Have folks found anything so far? What kinds of things are popping up?

ROBERT BOULAY: It’s a whole range of things, from in Ireland they found another prehistoric henge monument and passage grave in the Boyne Valley. There have been numerous prehistoric enclosures, circular enclosures, square enclosures, found in Wales and all throughout England and Scotland. And the problem is there are so many photographs being taken, you have to seize the moment and take the photographs. It then takes a long time to actually begin to assess it.

And I remember in 1989 when we had a really dry summer, it took us many months, if not into the following year, before we’d been able to just even look at all the photographs and see what it is that had been discovered. So it’s going to take some time before the real impact is known. But it is literally hundreds if not thousands of new sites and information about sites that we know, added information about that.

Because, you know, Roman forts where you can see the internal arrangements that we couldn’t before or roads running into them and associated sites around. So it’s building up the picture of the landscape, which makes it really interesting.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s good to see there is a little bit of a silver lining to this drought and heat.

ROBERT BOULAY: Absolutely. Yes.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Thank you, Dr. Boulay.

ROBERT BOULAY: OK, thanks very much. Bye.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Stay cool. Dr. Robert Boulay, director of endangered archeology in the Middle East and Northern Africa, University of Oxford is staying up late for us.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.