Renewable Energy Makes Waves In Oregon

5:02 minutes

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Jes Burns, originally appeared on Jefferson Public Radio.

This segment is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Jes Burns, originally appeared on Jefferson Public Radio.

A renewable energy project planned off the coast of Newport is taking a step forward. Oregon State University has submitted a final license application for a wave energy testing facility with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. If built, it would be the largest of its kind in the United States.

Oregon’s potential to use the motion of the waves to generate electricity is very high. But nationally, the development of wave energy has lagged behind other green energy sources.

Part of the delay is the time and expense involved in permitting new technology. Not only do companies have to pay to develop this kind of clean tech, they also have to go through a lengthy and expensive permitting process before being allowed to see if their ideas work in the real world.

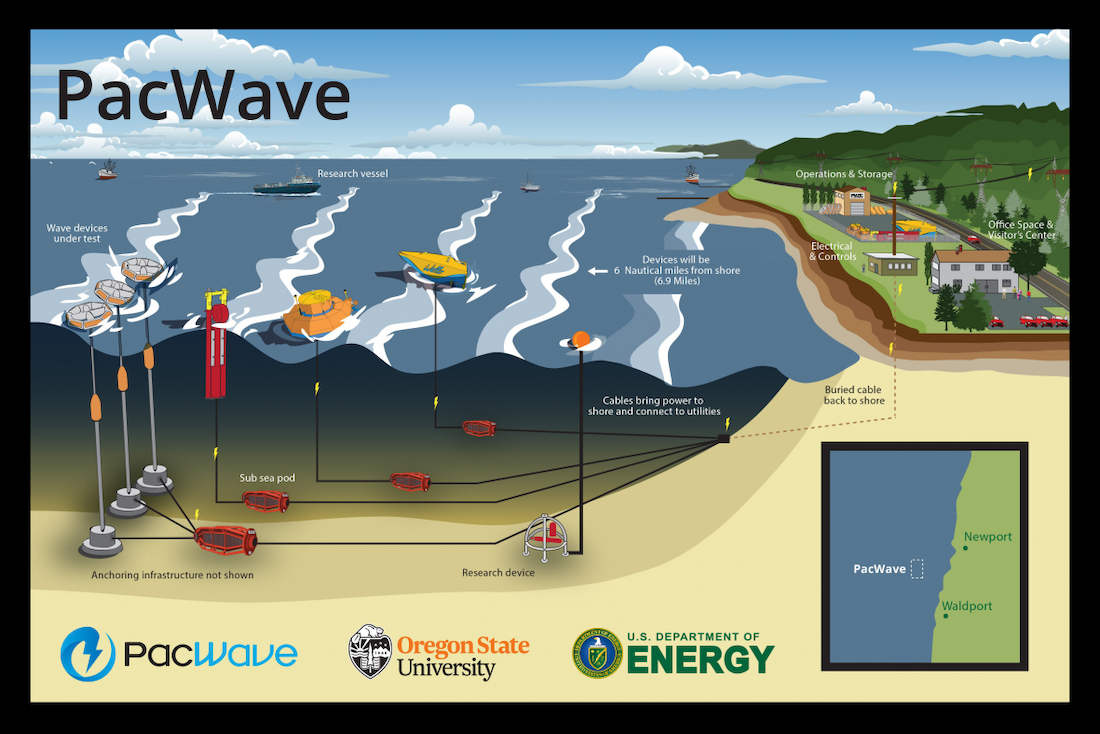

This is where Oregon State University’s PacWave South Project comes in. The university plans to create a wave energy testing facility about 6 miles off the Oregon Coast. The idea is that energy developers will be able to by-pass the permitting and just pay the University to test their wave energy converters in the water.

“If you look at the environment off the coast of Oregon, it’s one of the more harsh wave climates in the world,” said PacWave project manager Justin Klure. “If you can get past an Oregon winter with the technology and prove that you can not only survive, but also generate electricity, that would be the ultimate goal.”

The ultimate goal is to speed up the development of this largely-untapped source of clean energy – both in Oregon and nationally.

The footprint of the project includes four wave energy testing “berths” spread over an area of about 2.5 square miles in federal waters southwest of the coastal town of Newport. Each berth would have its own undersea cable that would run to shore and connect to the grid near Driftwood Beach State Recreation Site. At full capacity, the wave energy array could generate 20 megawatts of power.

“I don’t think we expect that right out of the gate. I think what you’ll likely see is a device in one berth, maybe two or three in another. And as the industry evolves over time, you could see a full buildout of up to 20 devices,” Klure said.

The public is expected to have a chance to weigh in on the FERC permit later this summer, although public meetings have not yet been announced.

The FERC permitting process, while the most involved, is one of many state and federal approval needed for the project to move forward.

PacWave South is partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. DOE says the goal is to have the test facility operational by 2022.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jes Burns is a science reporter with Oregon Public Broadcasting in Portland, Oregon.

IRA FLATOW: Now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

[RADIO JINGLE]

Local science stories of national significance, and you know when you hear the term renewable energy, you might think of what? The usual suspects– solar, wind, hydropower, even geothermal. But there’s also one that has almost unlimited potential that we don’t hear much about, and that’s the power of ocean waves. Wave energy has an estimated efficiency of as much as 50%. But efforts to harvest it have been very slow in the US.

Now a proposed project off the coast of Oregon hopes to boost wave energy development. Here with the story is Jes Burns, producer and reporter for Oregon Public Broadcasting Science and Environment Team. She joins us from Ashland. Welcome to Science Friday.

JES BURNS: Hey, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. So what exactly is this thing OSU is trying to build?

JES BURNS: Yeah, so Oregon State University wants to build a wave energy testing facility. This isn’t a building. This is a area of the ocean about 6, 7 miles offshore, 2.5 square miles, so a big chunk. And in that, they would have the ability for wave energy developers that are developing these devices to come in and test their buoys and their devices, all different kinds of configurations there.

And the kind of important thing here is that there are going to be undersea electric transmission lines that are going to connect back to shore. And so basically, these wave energy developers will be able to plug up to five each of these devices into a cable and then test how they interact together, how much electricity they’re producing, just how well they do out in the ocean environment.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re like giving them an underwater maker space to figure out how to do anything. Yeah.

JES BURNS: Yeah, yeah, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: That is cool. So you can hook up all the cables and do all kinds of underwater testing for wave energy. What kind of technologies are we talking about for harvesting wave energy? Is it like wind turbines, or how do you make electricity from motion waves?

JES BURNS: Well, you can make it through wind turbines out in the ocean. You can do tidal energy. This specific project is actually capturing the motion of the waves, using the kind of kinetic energy in the waves to generate electricity. Yeah, there’s all different kinds of concepts out there. This is a pretty early tech, so companies are just emerging with these.

A couple that I’ve seen– one is kind of the one you would think about, that it would be a buoy floating on top the water, anchored to the ocean floor. And then the up and down of the waves would be captured and then transmitted into electricity.

Another one I saw that I thought was really interesting was– I guess picture a large piece of spaghetti floating on top of the ocean. And it’s tethered on both ends. So it’s attached on both ends. And basically, as that noodle is floating, and the waves are moving it, it’s moving up and down, left and right. And basically, you would convert that motion into electricity. So just kind of noodles on top the ocean was another one I just thought was just an interesting concept.

IRA FLATOW: That does sound good. Well, why is Oregon a good place to test out this technology?

JES BURNS: We have a lot of waves. The wind blows. There’s big ocean storms. There’s a lot of wave energy potential. I actually spoke with the project manager for the OSU project, Justin Klure. He told me that the coast of Oregon is actually kind of the ultimate testing ground for this kind of energy technology.

JUSTIN KLURE: When you look at the environment off the coast of Oregon, it is one of the more harsher wave climates in the world. And if you can get past an Oregon winter with the technology and prove that you can not only survive, but also generate electricity, that would be the ultimate goal.

IRA FLATOW: People have objected to wind power offshore. What kind of opposition might you see with wave energy?

JES BURNS: Well, I anticipate, just based on other projects and marine areas off of the coast of Oregon, that the fishing industry is going to get involved in this. And Oregon has a thriving fishing industry– dungeness crab, salmon, pink shrimp. And so anything that impacts kind of where fishermen can go and where they can fish, they definitely kind of voice their concerns. OSU has said that they’re going to allow fishing, but I mean–

IRA FLATOW: Jes, I’ve run out of time.

JES BURNS: Yeah. OK.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we get the picture. Jes Burns, science and environment reporter at the Oregon Public Broadcast.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.