House Stalls On Bill To Compensate Victims Of Nuclear Testing

17:01 minutes

In July 1945, the US deployed the world’s first nuclear weapon during the Trinity Test. Since then, the US has tested more than 200 nukes above ground in places including New Mexico, Nevada, and several Pacific Islands.

In July 1945, the US deployed the world’s first nuclear weapon during the Trinity Test. Since then, the US has tested more than 200 nukes above ground in places including New Mexico, Nevada, and several Pacific Islands.

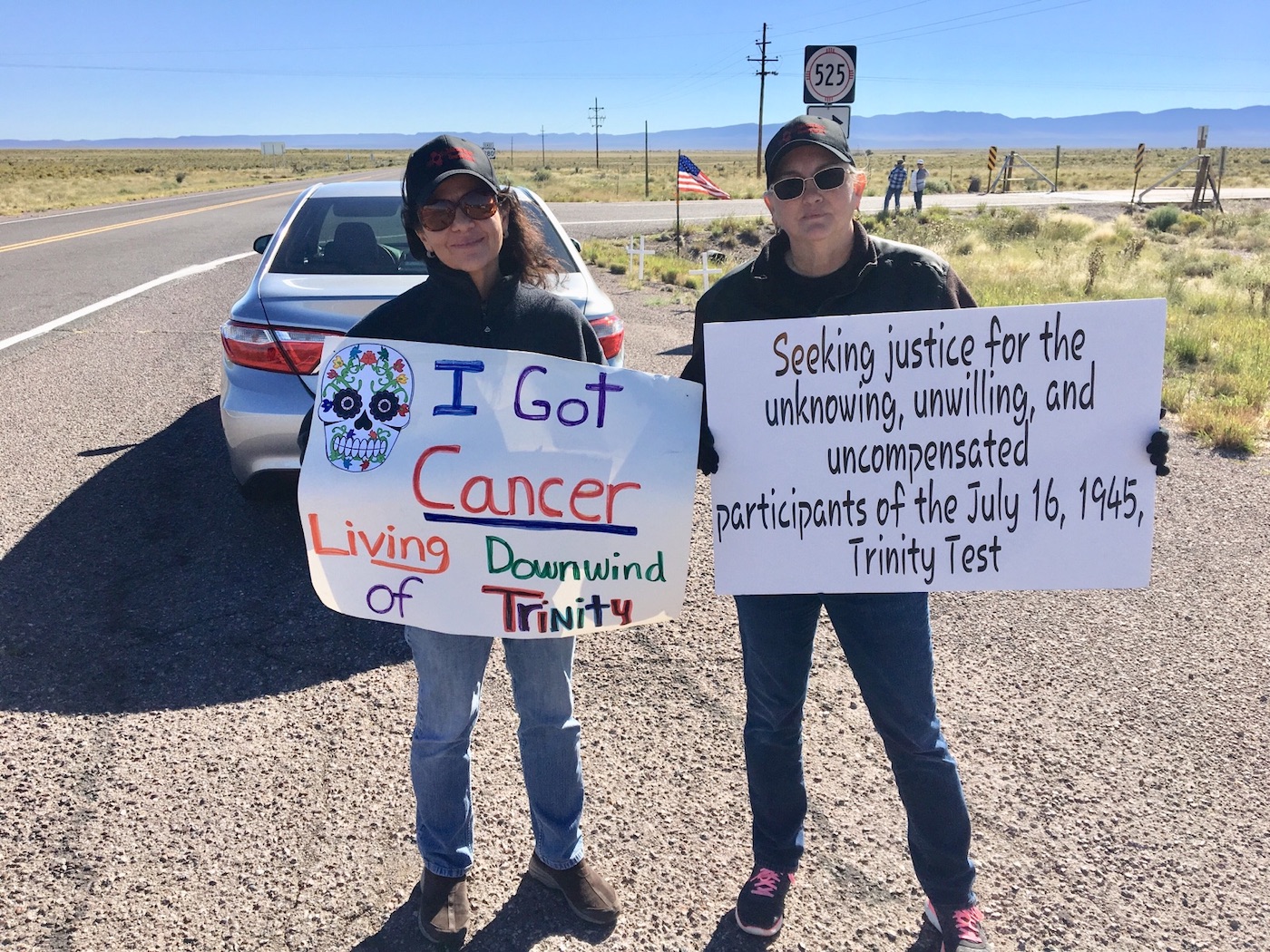

For decades to come, “downwinders,” or people who lived near those test sites, and those involved manufacturing these weapons, were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. They’ve disproportionately suffered from diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, and more.

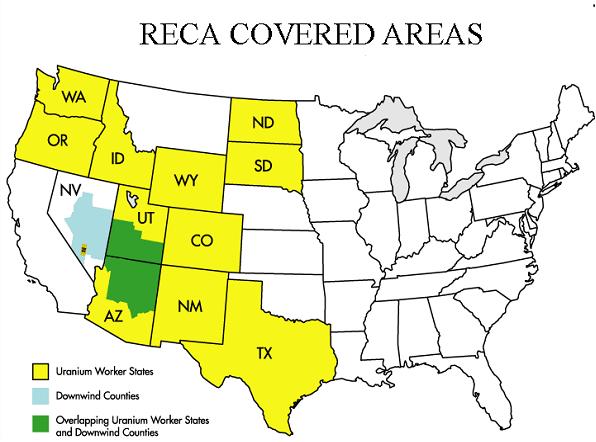

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) was established in 1990 to provide victims of the US nuclear program a one-time payment to help cover medical bills. But the program has fallen short of helping everyone affected—like the downwinders living around the Trinity Test site in New Mexico.

A new bill, which was passed in the Senate earlier this year, would expand the program to include more people and provide more money. It’s up to the House now to pass it, but Speaker Mike Johnson of Louisiana won’t call a vote. And the clock is ticking, because RECA expired on June 10. So what happens now?

SciFri’s John Dankosky speaks with Tina Cordova, downwinder and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium in Albuquerque; Loretta Anderson, co-founder of the Southwest Uranium Miners’ Coalition Post ‘71, from the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico; and Lilly Adams, senior outreach coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Subscribe to get updates on SciFri’s latest coverage of policy affecting our communities.

Tina Cordova is a Downwinder and is co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium. She’s based in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Loretta Anderson is co-founder of the Southwest Uranium Miners Coalition Post ‘71, from the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico.

Lilly Adams is senior outreach coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists in New York City.

KATHLEEN DAVIS: This is Science Friday. I’m Kathleen Davis.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And I’m John Dankosky. In July of 1945, the US deployed the world’s first nuclear weapon during the Trinity test. Since then, the US has tested more than 200 nuclear weapons above ground in places like New Mexico, Nevada, and several Pacific Islands. For decades, people who lived near these test sites– they’re called downwinders– as well as those involved in the making of these weapons were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation.

Now, they’ve disproportionately suffered from diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, and much more. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, or RECA, was established in 1990 to provide victims of the US nuclear program a one-time payment. But the program has fallen short of helping everyone affected, like the people living right around the Trinity test site in New Mexico. With the program set to expire in early June of this year, the senate passed a bipartisan bill that would expand the program to more people and provide more money.

Now, it’s up to the house, but Speaker Mike Johnson won’t call a vote on the bill saying that the price tag around $50 billion is just too expensive. So with RECA now expired, what happens next? Joining me to talk about this is Tina Cordova, downwinder and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Loretta Anderson, co-founder of the Southwest Uranium Miners Coalition, Post 71, from the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico, and Lilly Adams, senior research coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists in New York City. I’d like to welcome you all to Science Friday.

LORETTA ANDERSON: Thank you, John.

LILLY ADAMS: Thank you for having me.

TINA CORDOVA: Thank you, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Tina, I’d like to start with you. How are you feeling about this decision or, I suppose, this lack of a decision?

TINA CORDOVA: Well, honestly, we have felt the whole spectrum of things, anger, frustration, disappointment. You know, there’s nothing like being let down by your own government. And so I have felt the whole spectrum of things and that has been compounded by the fact that I’ve received numerous emails and telephone calls from people all across New Mexico who were traumatized by the idea that the government would let the program expire and that they would do nothing to address this issue, find no solution to this issue. People are devastated, and we need a solution. We’ve waited far too long.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So, Lilly, I want to get into the politics of this in just a minute. But could you tell me what groups have been included in RECA so far? How much money do they get?

LILLY ADAMS: So currently, RECA provides a small amount of compensation to three different groups. So the first are downwinders, which you mentioned those near above-ground test sites. And right now they’re eligible for $50,000. The second group is on site participants. Those are people involved in the actual above-ground tests themselves. And that often includes veterans involved in the tests. They’re eligible for $75,000. And then uranium workers– or some uranium workers are eligible for $100,000.

For people battling cancer, $50,000 is a pittance. You know, a single cost of chemotherapy treatment can be up to $100,000. So part of the bill that we’ve been supporting, our coalition would increase the amount of compensation to reflect the things like higher health care costs and inflation to make the compensation $100,000.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK, and do we know how many people are potentially affected? I mean, how far exactly are those dollars going?

LILLY ADAMS: Yeah, so unfortunately, the government did a very bad job of record keeping and of tracking people’s exposures. And so we don’t have a precise number. We know that so far in the over 30 years that RECA has been in existence that over 40,000 people have submitted claims. But like you said earlier, we also know that doesn’t nearly represent the scope of people who were harmed. And while RECA does provide that eligibility to certain groups, it really excludes so many who were harmed that are not covered currently.

TINA CORDOVA: Yeah, I think it’s important also to point out that when you talk about the downwinders that are included, it only includes certain counties in parts of Arizona, Utah, and Nevada but has never included the first people ever exposed to radiation as a result of a bomb which were right here in New Mexico? So the fund has never gone far enough.

And it’s never been based on proof. It’s been based on an assumption that if you lived in one of these downwind areas and you developed one of the radiogenic cancers, then you would qualify for the modest payment of $50,000 towards your loss of wages because you can’t work to help cover medical costs. And honestly, it’s a pittance. It’s nowhere near what people need to address those issues.

The original RECA amendments that were originally passed, actually, by the US Senate included health care coverage as well, which had to be stripped out to bring the CBO estimate down to $50 billion from $150 billion. And so they’re still balking at that price tag. And we’re still reminding them that there’s no price that you can actually place on a life. And so we bury our loved ones on a regular basis, and they claim it’s too expensive to take care of us.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And, of course, this is very personal to you, Tina. I know you’ve joined us on the program before. Maybe you can talk about your family’s impact from these tests.

TINA CORDOVA: Well, it’s pretty clear in my family– and my family’s not unique. We’ve documented hundreds of families in New Mexico, like mine, that are displaying 4 and 5 generations of cancer now since 1945. So I’m the fourth generation in my family to have cancer. And now I have a 24-year-old niece that was diagnosed at the age of 23 with thyroid cancer, the same cancer I have, a cancer that is well known to be radiogenic in nature.

My dad died from cancer. He was a four-year-old child at the time of Trinity, living in a community 45 miles away, drinking mass quantities of fresh cow’s milk and dipping water out of their cistern. And my dad developed tongue cancer.

He never drank much, never smoked, didn’t use chewing tobacco, had no viruses, developed two primary tongue cancers eight years apart that the last one killed him. And I’ve lost count of the aunts and uncles and cousins that have died. And it just goes on and on. And it’s not ending. And younger children are being diagnosed all the time.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So, Lilly, we’re talking about the federal government deciding whether or not $50, $75, $100,000 is enough to compensate people. Obviously, it does nothing to compensate people in the way that Tina’s has just described. So who else would reap benefits under this new expanded bill if indeed it were passed?

LILLY ADAMS: So it would finally include some of the downwind communities that have never been recognized as Tina said, for example, the folks around the Trinity test in New Mexico, as well as other downwind communities across the West, who we know now were also exposed. It would finally include uranium workers after the year of 1971. Right now there’s a cutoff date.

But thousands of workers continued working in the same very dangerous conditions. And then it would also include some additional communities that have been identified as affected by nuclear waste. So for example, in Missouri where nuclear waste was illegally and absolutely recklessly buried and is still affecting communities today–

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to turn to you, Loretta, because amongst the people who would be compensated are uranium miners. But only those who worked in uranium pits through 1971 are part of this RECA program. So why exactly is 1971 the cutoff?

LORETTA ANDERSON: The reason being the government is saying they did not buy the uranium anymore. It was companies. But yet they were purchasing the uranium from the companies. So we feel that the government is still responsible. There are so many of our people that are sick, suffering, and dying due to radiation exposure. No one ever warned our people.

No one ever told them that if you work in the uranium mines, you’re going to get sick. We are fighting for our lives, our people, our downwinders, our uranium miners. We’re fighting for our lives. It is so devastating. No one can understand the pain, the suffering that our people are going through, especially those that have to see their family members dying.

We do not have a cancer center here. It takes months to finally get diagnosed because we live so far away over 100 miles from specialists. And when they find out they have cancer or kidney disease, it’s too late. They go home and die. I had my grandfathers, my uncles, my aunties. My own father, he was a miner. He died of colon cancer. My mother worked in the office at Sohio Uranium Mines. She was diagnosed with pulmonary fibrosis. I have cousins. My brother in law’s– we’re all seeing the effects of what radiation exposure has done to our people.

TINA CORDOVA: Most parts of the American West, where people have been overexposed to radiation, are rural. And we don’t have access to health care. And Loretta has done an amazing job of explaining how difficult it is for us to access health care. Indian Health Service does not provide cancer treatment. So our Native people who had their poverty used against them, that’s how they got them to go into the mines without safety gear. They used their poverty against them, and they’re dying now. Generations of them are gone.

I go to meetings at Laguna Pueblo and on the Navajo Nation, and there’s all these widows. There’s no men anymore. We don’t have elders. We don’t have elders in our communities anymore. It’s not that it got safer to mine uranium. It’s just that our government wasn’t the only consumer. And so they passed the obligation to take care of people to industry and industry doesn’t take care of people.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to get back to you, Lilly, for a second. We talked at the very start about one of the reasons why potentially this bill has not passed, just the price tag of it. We’re talking about potentially $50 billion. The Speaker of the House has said that Republicans in his caucus aren’t on board for this bill, but it passed in the Senate on a pretty bipartisan basis. What exactly is holding this up, do you think, Lilly?

LILLY ADAMS: Yeah, I think, first of all, just raising the concern about the money, this should not be about the money. This is about taking care of people who are sick because they were poisoned by their government. And for all of these decades, Congress has just been offloading that cost onto those communities, onto the backs of families who are devastated by the medical costs and other associated costs that they’re having to deal with.

And it’s disingenuous because when the government has priorities, they find the money to pay for them. So we really feel like Speaker Mike Johnson, in raising that, is just– he’s trying to put a price tag on human life and dignity. And that’s completely unjust. But, yeah, raising the issue also of not enough Republicans being in support of this– I mean, I think simply it’s just not true. The Senate Bill passed with almost 70 votes, 69 to 30 in the Senate.

That is far beyond a supermajority in the Senate. That’s incredible in this day and age when our Congress is so divided. Congresswoman Cori Bush said– when you have Cori Bush and Senator Hawley fighting together on the same issue, you’ve got to pay attention, and you’ve got something very impressive happening.

And this is how our government works. We don’t need to have a consensus of all Republicans. We don’t operate by consensus. The way our government works is that we pass bills that a majority of our elected officials agree on. And we’ve seen that in the Senate. And the speaker should really give the House the opportunity to do the same.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This would give more money, $100,000, to people who qualify if this is passed. As Lily just said, we can’t put a price tag on it. We shouldn’t be talking about how many billions of dollars it costs if people have been poisoned. That having been said, there is a price tag being put on it, like $100,000. So, Loretta, to you, what does that do if that passes? How does that help people in your community?

LORETTA ANDERSON: That would help our people to be able to travel, to receive a diagnosis, cancer treatment, so many things within a livelihood. Right now, our people, they have nowhere to turn. Like I said before, it’s not going to help everything. But at least it would help with the travel, the expenses, the cancer treatments, gas going back and forth.

LILLY ADAMS: As folks have said, it won’t cover all of the costs that people are dealing with. But some of the people that we work with who are suffering from these cancers, they’re doing things like rationing care, deciding what care they can and can’t pay for because they just don’t have the funds. We work with people who their light bills and phone bills are not being paid because they need that money to drive to their appointments, people who’ve had their cars repossessed. We talk with veterans who this is what saves them from keeping their home or losing their home. So that increase really can make a huge difference in people’s lives even though it will never bring back the lives that have been lost.

TINA CORDOVA: Let me tell you something, John. New Mexico is one of the states carrying some of the highest medical debt in the whole country. We have a little over 2 million people living here, and we’re carrying $881 million, $1 billion in medical debt. It’s the primary reason that people file bankruptcy. An acknowledgment doesn’t go far enough. $100,000 doesn’t go far enough. But here we are.

And let me tell you something else. And speaking about the cost of this, we have spent close to $10 trillion since the inception of the nuclear programs in the United States. $50 billion is a pittance. It’s a pittance. And when we talk about support from Republicans, I just want to remind everyone that the states that we’re trying to add to RECA right now, the locations that we’re trying to add to RECA right now, they’re predominantly Republican. So this is an issue of Republicans and Democrats that have been affected but primarily Republicans. When Speaker Johnson chooses to look the other way, he’s looking away from his own constituents and his own voting public.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So what exactly happens with this bill next, do you think, Lilly?

LILLY ADAMS: Well, we are going to explore every and all possible options. The biggest thing is that Speaker Johnson can still bring this bill that passed in the Senate, S.353. He could bring that bill to the floor tomorrow or the next day that the House is in session.

And that can still pass. And that would be the fastest and best way to get people the justice that they need and deserve. But we will look at attaching this bill to any moving vehicles as we’ve done in the past. We’ll look to see if there are any possibilities with the NDAA, or the National Defense Authorization Act, which is an annual budget bill for the Pentagon.

We’ll have to look at everything. I mean, it’s incredibly cruel that we’re having to look at this after the program has already lapsed, which means that people can’t apply who otherwise would be eligible. But we’ll keep fighting. This is absolutely not over. If Congress was hoping that the program would expire and we would go away, they will find that is absolutely not the case. We will keep fighting.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Tina, first, do you have hope that this can still get through Congress?

TINA CORDOVA: I have great hope, and I’ll tell you why. Because every day some other good person out there joins with us and decides that they want to be a part of this movement to get this done– I have great hope. I know that there will come a day when Congress has to address this issue. We’re not going away, and we will not go away quietly.

LORETTA ANDERSON: That’s the same way I feel. I have hope. I pray. We have so many people praying, calling Mike Johnson, asking him, begging him to put this before the house.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Tina Cordova, downwinder and co-founder of the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Loretta Anderson, co-founder of the Southwest Uranium Miners Coalition, Post 71 from the Pueblo of Laguna in New Mexico. And Lilly Adams, senior research coordinator at the Union of Concerned Scientists in New York City. I’d like to thank all of you so much for joining us, and I wish you best of luck moving forward. Thank you again for your time.

TINA CORDOVA: Thank you, John.

LILLY ADAMS: Thanks so much.

LORETTA ANDERSON: Thank you, John. God bless you.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And we did reach out to Speaker Mike Johnson’s office for comment on this bill. And we have not heard back as of air time.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.