What’s Next For Quantum Computing In 2025?

17:15 minutes

It seems that every few months, there’s an exciting breakthrough in quantum computing, a kind of computing that takes advantage of quantum physics to perform calculations exponentially faster than our most advanced supercomputers. Last December, Google announced that its quantum computer solved a math problem in five minutes—a problem that would’ve taken a normal supercomputer longer than the age of the universe to solve. And earlier this month, Microsoft, coming off a quantum advance in the fall, told businesses to get “quantum-ready” for 2025, saying that “we are right on the cusp of seeing quantum computers solve meaningful problems.”

So, are we on the cusp? Flora Lichtman is joined by Dr. Shohini Ghose, a quantum physicist and professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada and CTO of the Quantum Algorithms Institute, for a quantum computing check-in and a look at when this futuristic technology could start to have an impact on our lives.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Shohini Ghose is an Associate Professor of Physics and Computer Science and is Director of the Center for Women in Science at Wilfred Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. Quantum computing. We keep seeing these exciting new headlines about breakthroughs, like just in the last few months, Google announced that its quantum computer solved a math problem in five minutes that would have taken a normal supercomputer longer than the age of the universe to solve. Microsoft told businesses to buckle up because we’re on the cusp of seeing quantum computers solve meaningful problems.

So are we on the cusp? Up next, we’re doing a quantum computer check-in. What advancements are at the top of the queue? Which can we throw in the queue bin? Here to parse the news is Dr. Shohini Ghose, a quantum physicist and professor of physics and computer science at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada, and CTO of the Quantum Algorithms Institute. Dr. Ghose, welcome to Science Friday.

SHOHINI GHOSE: Thank you. Glad to be here.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK. Before we get to the recent news, can you give us a refresher on what quantum computing is in a way that will not break my brain?

SHOHINI GHOSE: [CHUCKLES] I’ll do my best. So quantum computing is a very interesting and revolutionary approach to doing computing. So I think we’re all familiar by now with regular computers, which are actually quite simple machines.

Essentially, they’re just a bunch of switches turning on and off inside. If you look at your circuit board, all of those circuits are really just ways to convert all of our information that we’re inputting into a sequence of zeros and ones, binary digits or bits. So in that sense, it’s a very, very simple machine. And we’re kind of lucky that everything can be converted into just some sequence of zeros and ones.

It turns out that quantum computing is a broader paradigm for computing, where we don’t restrict ourselves just to specific values of zeros and ones, but we operate in this very strange new landscape where we allow for some possibility that the quantum bit or qubit is in a state of zero or some possibility that it’s in a one. And so it’s kind of like exploring a much larger landscape of all these in-between combinations of possibilities of zeros and ones, like 80% zero, 20% one, which all may sound like it’s getting confusing, and there’s a lot of uncertainty in it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Right, this is where the brain breaking begins.

SHOHINI GHOSE: Exactly. So don’t worry. This is actually quite counterintuitive compared to what we normally think about computing, which is what makes it, on one hand, confusing, but on the other hand, powerful. So really, what has happened in recent years is this shifting of how we approach this idea of uncertainty and looking at that entire spectrum of possibilities between zero and one.

And if you’re very clever, we can build these pathways through this computational landscape to reach the answer faster, based on being able to control these possibilities, what we call superpositions of zeros and ones. So in a way, you might think of it as like having this probability wave that flows through your problem landscape. And if you can control the wave, you get to your answer actually faster.

Sometimes flowing to your answer is actually faster than jumping discretely using zeros and ones. So maybe that helps to try to visualize this very peculiar new framework.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yes, yes, definitely. I mean, and is the result that a computer can do sort of multiple calculations at once? If a bit can be more than just a zero or a one, if it’s more than the binary, does that mean it can sort of explore different pathways at the same time?

SHOHINI GHOSE: Yeah, but I want to be careful there. I know that often, quantum computing is described as exploring all possible values all at the same time. Yes, in a sense, that’s true because, of course, when we say superposition, it’s that idea of more than one possibility at the same time.

However, when we get to the final answer, the trick is that you can only eventually get to the one solution, right, which is some particular specific string of zeros and ones, which is your final answer. It’s not enough just to calculate everything and all possibilities at once, because the final answer, then, could be any one of those possibilities.

So the key is that, yes, you explore all these possibilities, but you have to explore them cleverly, not just leave it at, oh, you can do it all at once, because if you do it all at once, then you might get any one of those possibilities. And there are many more wrong outcomes than there are correct ones.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Ah.

SHOHINI GHOSE: So there’s more to the game.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What do quantum computers look like? What should I picture when we’re talking about them?

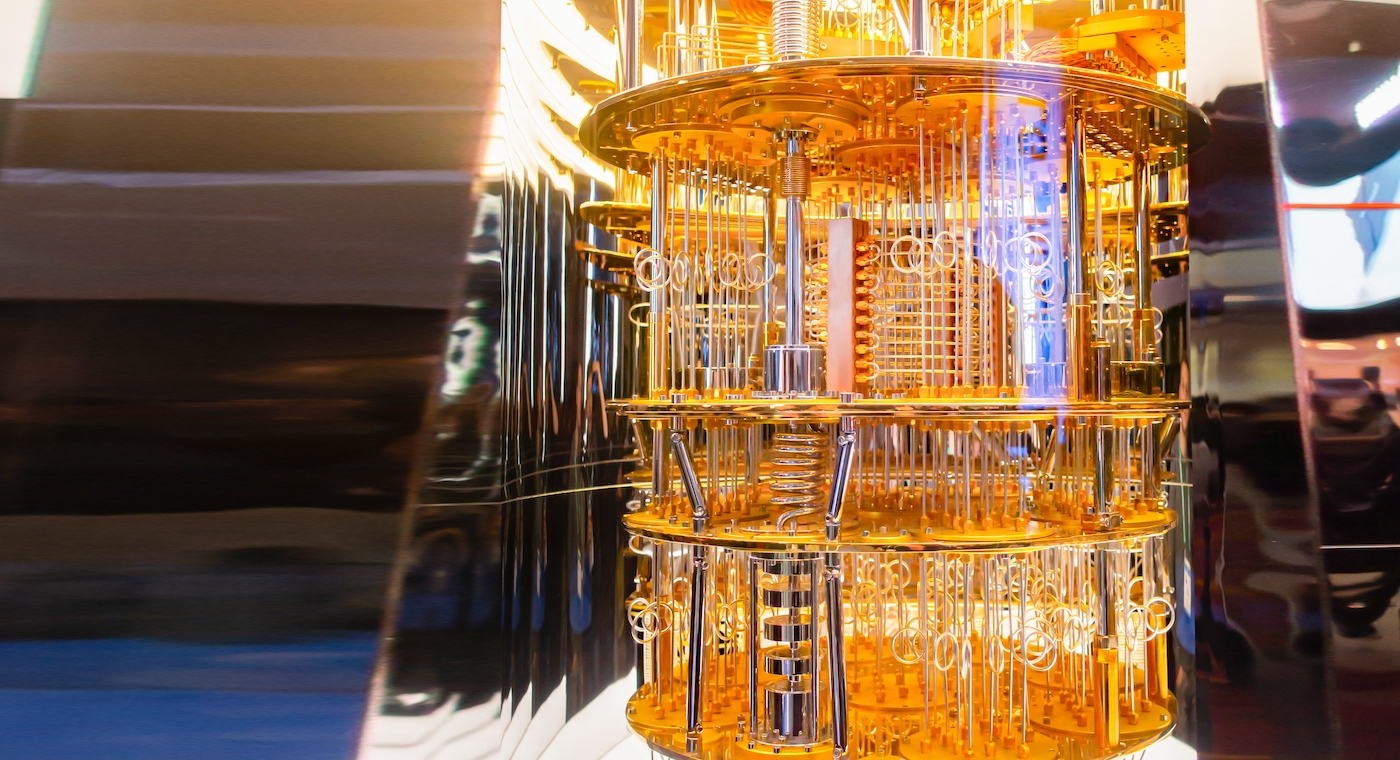

SHOHINI GHOSE: Well, I think if you google quantum computers, the one image that comes up a lot, you’ll see is a very amazing, sort of very different kind of image. It doesn’t look like a computer. It looks more like this golden chandelier. [CHUCKLES] And that is a particular type of quantum computer that’s being built by companies like IBM and Google and others around the world.

But most of what you’re actually seeing in the image is all of the control and the electronics and the cooling systems you need to operate the processor. The processor itself is actually quite small. It’s a small little chip that is very hard to see. So that’s one image of a quantum computer. There are others, but none of them look like our current laptops.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s check in on some of these recent advances. So in December, Google announced that its quantum computers solved this problem that would take existing supercomputers longer than the age of the universe to solve, which sounds very cool. Is it cool?

SHOHINI GHOSE: It is definitely cool.

[CHUCKLING]

But– there’s always a bit of a but– it’s cool in the sense that as a researcher myself, it’s exciting because this is a standard benchmark math problem that is used to try to understand the performance of quantum computers. So in that benchmarking test, Google did show that they were able to solve the problem very fast.

And the reason this benchmark is used, this particular math problem, because it is actually very hard, even for supercomputers, to solve the problem. And it’s not really a solving of a problem. This benchmark problem is actually a way to try to sample random numbers. And it turns out that’s quite difficult for supercomputers to do, whereas Google was able to complete that task quite fast.

But it is, in fact, a made-up math problem. It’s not like solving that problem actually leads to any particular useful real world application, like maybe helping to design better molecules for chemistry materials design, for example, or some kind of a health care drug development things. So at that level of real world application is not there yet. So on one hand, it is exciting, but on the other hand it’s not real world.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, it’s not real world. Were there any other pieces to that advance that signaled we are in a new phase of quantum computing?

SHOHINI GHOSE: Yeah. One other very exciting aspect of that announcement was that Google was able to address this question that comes up a lot, and it’s one of the biggest challenges for quantum computing development. And that is the question of errors.

So quantum computers actually are very, very difficult to control precisely because even the smallest disturbance will throw it off, and there will be errors in the computation. It’s kind of like our regular computers. These days, we don’t see it much, but there used to be those overheating problems. And computers sometimes freeze up even today.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yes, the fan goes on, and then nothing works anymore. Yes.

SHOHINI GHOSE: Exactly. So with quantum computers, the problem is infinitely worse. For example, Google’s machine and IBM’s machine, these computers have to be cooled down to temperatures that are colder than outer space.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow.

SHOHINI GHOSE: So even the tiniest amount of heating causes errors. And it’s not just a heat question. Anything that interacts with this quantum processor will throw it off. So they’re very, very fragile. What Google did that’s exciting is that they used this framework that we call quantum error correction, where you can actually take each of these individual quantum bits or qubits, and by coupling all these qubits together, you can, in a sense, reduce the error as you add more and more qubits.

Normally, you would think that the errors would go up because there’s even more qubits. They’re all going to have errors, and that will multiply. But there is this clever framework where you can actually reduce error correction, as long as each of the qubits has a particular threshold of error and failure.

So what Google was able to show is that as you increase the number of qubits, you can actually reduce the error. And obviously, that’s a very important piece of being able to scale up and build large-scale quantum computers. So that was very exciting.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Why are companies like Google and Microsoft and IBM working on quantum computing? I mean, is this akin to sort of like the race to develop AI, where these companies want to own the market because quantum computing could be applied to a million bazillion things, and we can’t even dream up the applications yet? Like, is that the right analogy, or is there something else going on?

SHOHINI GHOSE: Well, yeah. In the end, quantum computers can unlock huge performance advantages in certain types of areas. So one of the key applications, which kind of kickstarted this whole field, was to solve this one math problem, which sounds kind of like a fairly simple problem. And that’s factoring, meaning if I take a number like 15 and ask, can you find the factors? well, that’s easy. That’s 3 times 5.

But if you go to numbers that are, let’s say, 100 or 200 digits long, even our supercomputers have a hard time cracking that problem. And this is an important problem because hard math is actually what keeps all of our information safe, because it’s at the foundation of encryption systems. So, for example, if a hacker wants to hack your passwords, actually, that encryption is based on factoring. So the hacker would have to know how to factor large numbers. And it turns out that’s computationally hard, and that’s what keeps our information safe.

Turns out quantum computers can actually solve a problem like factoring exponentially fast. So this is actually what got everybody to wake up and say, oh, my gosh, if you can build that kind of large-scale quantum computer, you actually can basically read everybody’s secrets, and hack into passwords, and find out about people’s finances and health care records and things like this.

So that’s one of these big, big applications, and that has led to this race around the world to try to be the first to get there. But that’s only one. There’s other possible applications, as I was saying, in developing drugs and doing the simulations you need to understand molecules and quantum chemistry.

There’s also applications in being able to solve optimization problems, such as trying to get the best sort of supply chain, right? That’s an example of an optimization problem that we see all the time around the world. So there are definitely many areas where quantum can benefit. But it’s not that it’s going to replace everything that we do with our regular computers.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I know the US and China are both spending billions on quantum research. What do you make of this?

SHOHINI GHOSE: [LAUGHS] Well, you’re right that there’s definitely a lot of funding, and in fact, there’s more than US and China. I’d say, as of the last count, there’s been over 30 different governments in the world that have announced national quantum strategies. And I think the reason there is because it’s recognized as something that is very critical to the security of countries. So it is related to sovereignty and security of data.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do you see this as a type of arms race?

SHOHINI GHOSE: I think yes, it is very similar to what we’ve seen historically with arms races because it can be used. Absolutely it can be weaponized, this technology. Governments are racing to build out plans because it’s not just about having the technology to deploy, but also to be able to defend against the technology being deployed against their own citizens. So in that sense, absolutely, there’s a lot of similarities with an arms race.

FLORA LICHTMAN: We’ve been talking about encryption and state security. Do you see quantum computers changing my life, changing our listeners’ lives, in meaningful ways?

SHOHINI GHOSE: Yeah, so quantum is not really a technology that’s going to replace our current computers because honestly, our laptops are just fine for almost everything that we do on an everyday level. It’s not like I wake up every day and need to solve a complicated molecule problem.

So if I’m doing email, my laptop is just fine. But even with email, what will be impacted going forward is that on the back end, every time we send email, we are sending encrypted data. So the encryption on the back end will start to change, and we will be shifting over to what we call post-quantum encryption, which is a way to try to protect against future hacking by quantum computers.

And eventually, we’ll be sending data through what we call quantum networks, where our information is actually being encoded using quantum information built into qubits. And just like we don’t see the encryption running on our current computers, we probably won’t see it, going forward, on our laptops and devices. But it will be there, so it will be impacting us. We just perhaps will not see it every day.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Are people using quantum computers outside of the lab? Like, are they outside of the demo space at this point?

SHOHINI GHOSE: For the most part, they’re still in development. However, there are certain areas in which there is already what we call real-world, ready-to-use kind of potential applications, that there are companies that are accessing this. So for example, there’s a company called D-Wave, which offers a quantum device that is actually very much tailored to do one type of problem, and that is optimization kinds of problems. Everything is an optimization problem at some level.

So like I was mentioning earlier, if, for example, you wanted to find the best routing system for your delivery trucks, they have a very, very complicated algorithm that they need to run to be able to deliver all of your packages. And you know how we get really annoyed when it doesn’t come within the next day? It’s actually quite a hard, logistical problem.

So in the back end, there’s always some kind of an algorithm running to try to optimize how all those deliveries work. And that’s one example of optimization. So there are companies that have used that tool to actually improve their optimization calculations. So it’s happening. It’s just not a universal quantum computer. It’s specifically for optimization. But it’s definitely real world already.

FLORA LICHTMAN: How do you see quantum computing playing with AI and machine learning?

SHOHINI GHOSE: That’s a great question. I think the future is really going to be in this hybrid space, where both quantum and AI will be applied to whatever is the computational task, where some parts of the task will be done using the quantum processor, some parts will be done using machine learning, so that the combination will provide you with the optimal performance.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I want to come back to where we started. Do you think we’re on the cusp of something big with quantum computing?

SHOHINI GHOSE: It’s always very hard to predict the future of any technology. I think we’ve always got it wrong. But given that disclaimer, [LAUGHS] I will say, as a scientist, yes, I am quite excited in all of the progress that has been made. And I’d say that it’s faster than I would have predicted.

And I think the big, exciting moment will happen when somebody announces, yes, we have solved an actual real-world problem. Maybe it’s in healthcare. Maybe it will be in finance. My guess is it’s going to be in some kind of quantum chemistry problem, which might be applied to material design or biology. And that’s, I think, coming. It’s in the next few years, I think, we’re going to see some very exciting announcements.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I really appreciate you walking us through this today. Thank you.

SHOHINI GHOSE: Thank you.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dr. Shohini Ghose, a quantum physicist and professor of physics and computer science at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada, and CTO of the Quantum Algorithms Institute.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Dee Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.