Amid The Pandemic, Other Diseases Still Lurk

17:11 minutes

While all eyes are currently on the COVID-19 pandemic, the coronavirus isn’t the only disease circulating the world. Lockdowns have hindered access to medical care, and supply chains for both tests and medications have been disrupted. With countries allocating limited public health resources to battle COVID-19, longstanding public health threats like tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDS may be at risk of resurging.

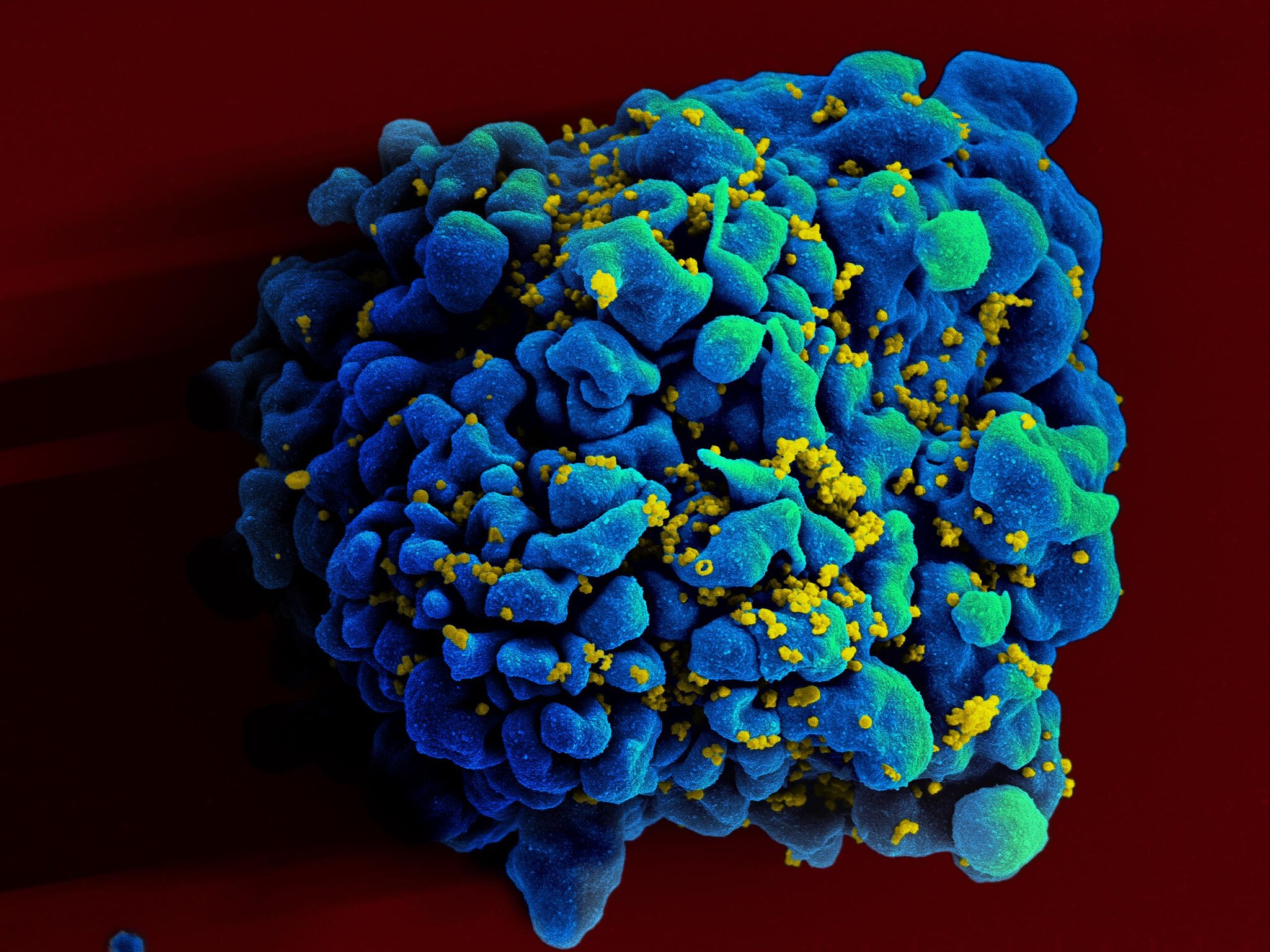

However, there is also hopeful news for communities facing HIV/AIDS. Last week, a study published in the journal Nature examined 64 unusual people who seem to be able to naturally keep HIV at bay. Researchers investigated what makes these so-called ‘elite controllers’ able to manage their infections. They now think powerful T cells—a type of white blood cell which helps regulate the immune system—may hold a clue to these cases.

Furthermore, earlier in the summer, a trial of a long-lasting injectable drug to prevent HIV infection was found to be at least as protective as the existing “pre-exposure prophylaxis,” or PrEP drug, which must be taken daily.

Health and science reporters Apoorva Mandavilli of the New York Times and Jon Cohen of Science join Ira to discuss recent HIV/AIDS developments, and to reflect on 40 years of AIDS research.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Apoorva Mandavilli is a health and science reporter at the New York Times.

Jon Cohen is a senior correspondent for Science. He’s based in Cardiff, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. While all eyes have been on the COVID-19 epidemic, COVID is, by far, not the only disease around. Other global health threats from tuberculosis to malaria continue, and we’re headed into the 40th anniversary year of the first public descriptions of what would come to be known as AIDS. Joining me now for an update on where the fight against HIV stands are two reporters covering diseases and global health. Apoorva Mandavilli, a health and science reporter at the New York Times, and Jon Cohen, senior correspondent at the journal Science, welcome to both of you.

JON COHEN: Thanks so much.

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Thank you for having us.

IRA FLATOW: Apoorva, you wrote recently that while people were fighting coronavirus, some of the big global health issues, from TB to HIV, are being affected. Tell us about that, please.

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Well, as you know, Ira, HIV, and TB, and malaria, are a huge problem in many parts of Africa, and Asia, and even Latin America. And in those places, the lockdown as well as the pandemic have really affected the efforts to contain those diseases, so it’s really hard for people to get to clinics and be diagnosed, it’s difficult for them to get medication, and it’s difficult for doctors to keep track of whether people are taking their medications on time.

And all of those steps along the way are what we need to be able to control in order to prevent deaths from those diseases. I think a lot of people may not realize that tuberculosis is still the biggest infectious disease killer. And last year, it killed about 1.5 million people. So these are not trivial diseases.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, they have not gone away, even though they have gone off the radar screen, right?

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: That’s right. I think people think of TB as an old disease. And it is very much that, but it’s also very much present, and it looks like it is going to be an even bigger threat because of the pandemic and the coronavirus derailing all of the efforts to control the TB pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, let’s talk about that. Some of the resources that supplies and tests that would normally have gone to those other diseases, are they being used up by the coronavirus?

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: There is a test called the GeneXpert, which is used to diagnose TB, and it’s a very effective diagnostic tool. But as it turns out, it can also be used to diagnose the coronavirus infection, which, in many ways, has being great for these countries because they were prepared to diagnose the coronavirus infections.

But at the same time, it meant that in these places where there are very few resources, all of the people in the clinics and all of the resources went towards the pandemic. And all of a sudden, TB was, again, a back-burner issue. And a lot of hospitals actually shut down everything except the coronavirus.

And so all of the efforts and diagnosis went towards the virus. And people are not being diagnosed with TB as much anymore. I mean, in some countries, diagnosis of TB have fallen by something like 70%. If you’re not getting diagnosed, you are probably spreading it to other people, your disease is progressing, you are much more likely to get really sick, and you’re much more likely to die.

IRA FLATOW: That’s really sad news to hear. You wrote about difficulties in getting the drugs needed to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission, possibly causing a surge in HIV cases in Africa.

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Right, so we actually have very good drugs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. But one of the problems with the pandemic has been that the lockdown has made it really difficult to get the medications to where they’re needed. Some of that is because there are only very few places where these drugs are made.

For example, India is one of the places, and China is the other, where most of these drugs are manufactured and without being able to get the drugs into the countries. But also, a lot of women are not showing up at the clinics, because they’re afraid of getting infected at the clinics or they’re not able to because of the lockdowns. And so they’re not getting the medications they need to prevent that mother-to-child transmission. So we will probably see and have already been seeing an uptick in the number of babies diagnosed at birth.

IRA FLATOW: Jon, you’ve written, and so have you, Apoorva, about a study that came out in nature last week about people called “elite controllers.” Jon, what is that? Can you tell us about that?

JON COHEN: We’ve known for a long time that there are some people who become infected with HIV and the virus doesn’t harm them. Over the years, their immune systems remain normal, and they don’t take antiretroviral drugs. And it’s been studied intensively, but usually the studies are of three or four of these elite controllers, and they’ve found some hints as to why they control the virus, and it does seem, in some cases, as though they have unusually good immune responses against the virus. But it doesn’t explain everything.

And this new study looks at 64 elite controllers and a very deep dive into their chromosomes and discovers something really eye-popping. The virus weaves itself, its genes, into our chromosomes. And they found that in the elite controllers as compared to people on treatment, they more frequently, far more frequently, have the virus in parts of their genomes and parts of their chromosomes that can’t copy the virus. They don’t have the machinery necessary to go from the DNA of the virus into new viruses.

So they’re throwing the virus into what are called gene deserts. And that’s a fascinating insight. It’s going to be difficult to translate that to help everyone because there are 38 million infected people, and elite controllers make up half of 1% of those people. But that’s how progress happens. You crack open the door, and this tells us something we didn’t know.

IRA FLATOW: Pretty rare is right. I mean, the researchers looked at 64 people. That’s not a lot of people, is it?

JON COHEN: Well, it’s a lot of people considering how few of them exist. And the sequencing that they did of their DNA is really intensive. It’s a tremendous amount of data. They looked at thousands of genome sequences of HIV in these people as compared to the control group.

So it might not sound like a lot of people, but, in reality, the amount of data is a flood of new data that makes a really strong case that they’re throwing their HIV DNA into these gene deserts. And it raises a provocative question of, how did they do that? Why did they do that? And it may well be linked to their immune responses.

And the leading theory is that their immune responses got rid of the really good HIV DNA in their genomes. HIV wants to be inside of a gene, and genes only make up a percent of our genomes, you know. We have 3.2 billion DNA building blocks in us. Genes are a tiny part of that. HIV targets those. And these people selectively got rid of those. That’s interesting.

IRA FLATOW: Did they get rid of them forever? I mean, are they disease-free? Can they be called cured now, Jon?

JON COHEN: You know, it’s something of a philosophical question. No, they are not cured, but they’re not on drugs, and the virus isn’t harming them. In one person in this study of the 64, she had broken HIV DNA in her genome, and “no replication competent” is the scientific nerdy words, but no DNA that could make new viruses. She may well be cured because there’s no evidence that she has any HIV in her that can make new HIVs.

The other people all have evidence of HIV in them that can make new HIVs. And we’ve seen lots of cases of people who appear cured, who stop all treatment, and the virus comes back two, three years later. So it’s a dicey proposition to say someone is cured. But for all intents and purposes, they are quote unquote “functionally cured” because they live their lives as though there is no virus in them. It doesn’t do anything to them.

IRA FLATOW: Apoorva, how different is this from other people that have been said to be quote “cured” of HIV, the virus eliminated over a long course of antiviral therapy?

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Well, only two people have really been cured of HIV before this– the Berlin patient and the London patient, Timothy Ray Brown and Adam Castillejo, they both were treated for their cancers with a bone marrow transplant, which is an extremely invasive and risky procedure.

And basically, they had their immune systems wiped out, and they got a whole new immune system. This isn’t something that we can really do for the 37 million people who are infected out there. So it’s not really a very practical solution, but it gave us some hope that a cure is possible, that it is possible to completely get rid of HIV from your body.

Now this newest case, Loreen Rosenberg, she’s been infected since 1992. And as Jon was saying, there is really no live virus left in her body that they could figure out can multiply itself. And so she is, for all intents and purposes, cured.

One of the cool things about this study that they were able to do is they looked at just a massive amount of her blood cells, which, these are the kinds of things that we couldn’t really do a few years ago. And they use techniques that are just very new and very cool to be able to look at an enormous number of cells and to look everywhere in the genome, and they couldn’t find any trace of virus. So the scientists that I spoke to seem pretty comfortable with calling her a cure.

IRA FLATOW: She had a funny response when I asked her, do you think you’re cured? She said, I don’t know why people ask me that. The virus has never done anything to me, so why would I be cured? Earlier this summer, Jon, there was some other hopeful news with regard to something called pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP. Tell us about that, please.

JON COHEN: So PrEP is the idea that– it’s kind of like if you go to a country that has malaria, you can take drugs to prevent malaria. Well, you can do the same thing with HIV. The drugs that treat people for HIV, the antiretrovirals, they work as preventives. And that’s what PrEP is. That was first approved by the FDA in 2012. It’s been around for a long time. And there’s solid evidence that it works.

The problem is that, for it to work, you have to take daily pills. And a lot of people don’t want to take daily pills who aren’t living with a virus. And the advance that came out was an injection that offered better protection even than the daily pills. And that could last for a few months.

Some people aren’t going to want injections. Some people are going to want to take pills. It’s kind of like contraception. Some people are going to want condoms. Some are going to want birth control pills. Some are going to want IUDs or diaphragms. But we have a menu available to prevent pregnancy. And the same idea is occurring in the HIV world.

IRA FLATOW: Apoorva, do you see this as changing the equation for people in communities affected by HIV? I mean even financially, is this more competition in the PrEP drug market?

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Absolutely, I mean, we’ve only had one company in this space before, Gilead, they had Truvada, and then they more recently developed another drug called Descovy. And they’ve had, basically, a monopoly, and there’s been a lot of issues with activists alleging that Gilead is setting the prices way too high, that it’s profiting from patterns that the tax payers helped to develop. And so it’s always nice to have competition in this space.

And this option, in particular, is really welcome because it’s long-acting, and people wouldn’t have to take the pill every single day. There’s also a lot of stigma associated with taking a medication like that. There are a lot of women in parts of the world. There are people who like to travel. For a lot of people, it’s just not a very practical option to have to take something every single day. In this case, they would be able to just go and get the shot and then, that’s it. You don’t have to think about it for the rest of that period.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday. In case you’re just joining us, we’re talking about HIV/AIDS and other global health issues in the time of coronavirus, with my guests Apoorva Mandavilli of the New York Times and Jon Cohen, senior correspondent at the journal Science.

Let’s zoom out and look at the big picture. We’re heading into the 40th years since AIDS was really talked about in public. And I remember back 40 years ago, most of the money went into finding a treatment for aids and, really, we still haven’t found a vaccine against it, whereas opposed to COVID-19, the majority of the effort is going on to finding a vaccine. We have hundreds of people looking for potential vaccines. Jon, what’s your perspective on that?

JON COHEN: In 1989, I started to work on a book about the search for an AIDS vaccine. And I had the foolish idea of proposing a book about one year in the search for an AIDS vaccine. And I sold that book proposal. It took me 12 years to complete the book. The book came out in 2001, and it was about why there wasn’t an AIDS vaccine and how the field was in disarray.

So HIV surfaces– and we don’t know what causes AIDS. We don’t know that HIV is the cause. That takes several years. In the case of COVID-19, we know, on January 10th, and some people knew earlier, that there was a new coronavirus that resembled SARS. And you have to know what the cause is to make a vaccine. You can make a treatment for something without knowing the cause. It’s better if you know the cause, but the truth is you can treat some diseases without really understanding cause. But a vaccine, that’s not the case.

And HIV is a much more difficult virus to stop than SARS-CoV-2 And we know that for lots of reasons. Number one, most people who gets SARS-CoV-2 recover and get the virus out of their body with their immune system. That’s not what happens with HIV.

And if you look at animal studies where you give a vaccine to the monkey and then challenge it with the virus, in the HIV world, the monkey model really struggled for many years and still struggles to show that you can protect monkeys with a vaccine.

With SARS-CoV-2, almost everything works to some degree. So I’m incredibly optimistic, and I think now I should do one year in the search for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine because it just doesn’t look like that tough of a scientific problem.

IRA FLATOW: Apoorva, with studies like we’ve been talking about today, do you think we’re looking towards a time when HIV will be controllable or even eradicated?

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: It’s looking more optimistic now in terms of the research than it has in a very long time, partly because we have learned all of these insights in the last few years. There’s also a long-acting drug, the same company that made the long-acting preventive that we were just talking about, the PrEP also has a long-acting drug that people would be able to take once every month, or once every two months and not have to be treated every single day.

I think there are a lot of really positive developments along those fronts, but to go back to what we were talking about earlier with the pandemic and that derailing HIV prevention and treatment efforts, I think the numbers for the next few years are going to be tricky again because we are losing a lot of progress during this pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: And resources going towards the pandemic, that might be going toward other diseases and even HIV, just bringing us back to where we started this discussion.

JON COHEN: Exactly. It looks like the pandemic is going to set us back by about a decade or 15 years if countries don’t shell out the resources that they need to keep things on track.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’ve run out of time. I’d like to thank my guests, Apoorva Mandavilli, a health and science reporter at the New York Times and a Science Friday alumnus, and Jon Cohen, senior correspondent at the journal Science. Thank you both for taking time to talk with us today.

APOORVA MANDAVILLI: Thanks for having us.

JON COHEN: Thanks so much, Ira.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.