Preparing for a Stellar Show

12:04 minutes

This coming Monday, much of the United States will be able to see at least part of the transit of Mercury—that is, when the tiny dot of our closest planetary neighbor moves across the disk of the sun. Dean Regas, outreach astronomer at the Cincinnati Observatory, encourages listeners to safely observe the astronomical phenomenon by making a suitable solar viewer.

Dean Regas is an astronomer and host of the “Looking Up With Dean Regas” podcast. He’s based in Cincinnati, Ohio.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Sky watchers across the globe are hoping for clear skies next Monday, hoping to catch a rare astronomical event. The transit of Mercury. No, I’m not talking about some astrology thing here. You want to watch yourself? Here to tell us about the transit and other things we can see if we keep looking up is Dean Regas. He’s the outreach astronomer at the Cincinnati Observatory and co-host of the PBS program Star Gazers.

Talking today with us from WVXU in Cincinnati. Welcome back to Science Friday, Dean.

DEAN REGAS: My pleasure. Good afternoon.

IRA FLATOW: What is the transit of Mercury all about?

DEAN REGAS: I know, it’s a cool sounding name.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, love it.

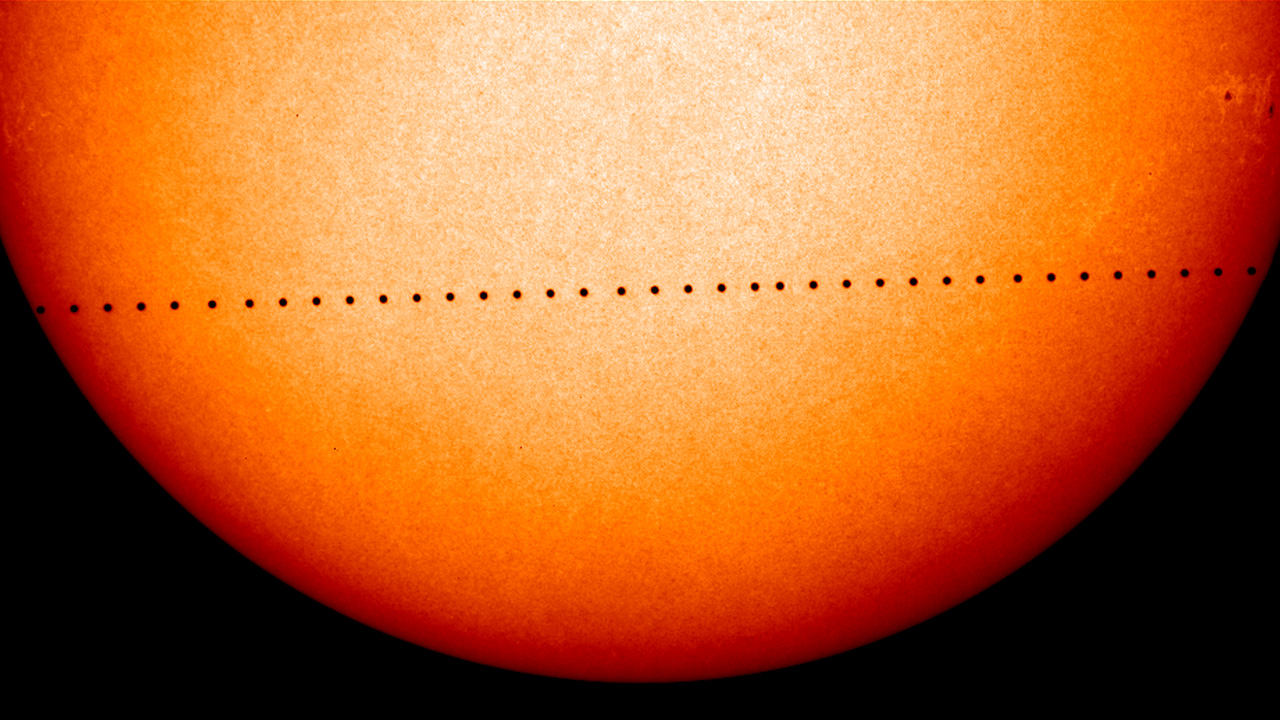

DEAN REGAS: That’s for sure. This is the tiny planet Mercury. It’s going to come between us and the sun on Monday, most of the day, between 7:12 AM Eastern daylight to 2:42 PM. So it’s a seven and 1/2 hour event where Mercury will just show itself as a little dot going across the surface of the sun. Like a miniature eclipse.

IRA FLATOW: So anybody when the sun is up can see it on Monday?

DEAN REGAS: Exactly. So if you’re on the East Coast, you can see it just after the sun rises right at 7:12. If you’re on the West Coast, you’re going to have to wait a little while. It will already be starting, the transit will already started by the time the sun rises for you guys out west. But at some point in the day, everybody in the United States will be able to see it. Most of Europe, South America, Africa, almost the entire world gets to see it other than if you’re in Australia and New Zealand.

IRA FLATOW: All right, they’ll see the next one.

DEAN REGAS: Yeah, they’ll get the next one. Three more years, they’ll get the next one.

IRA FLATOW: They’ll the next one. But we all know you just can’t look at the sun, right?

DEAN REGAS: That’s right, that’s right. always told me, Dean, never stare at the sun. But now that I became an astronomer, I can do that. I’ve got special filters that you can put on the end of telescopes or binoculars to be able to see it. And there’s two parts to this. So you have to do one, you have to use safe solar viewers. And two, you’re going to have to magnify the image. So that means pinhole cameras and eclipse glasses just looking at it, you won’t see it. Mercury is that small compared to the sun.

So we’re talking a planet that’s about 3,000 miles in diameter going in front of a star 865,000 miles in diameter.

IRA FLATOW: Can you make a home little doohickey to see it?

DEAN REGAS: My favorite way to do it is use a pair of binoculars, and you project an image of the sun. So you let the sunlight come through the binoculars, you cover one of the oculars, I guess you call it. You cover one of them, let light come through just the other part of the binoculars, projected onto a white piece of paper. You can even focus it using the focuser on the binoculars.

You throw the image about a few feet down and you’ll see an image of the sun. You can see sunspots on it, you can see hopefully even the little spot of Mercury. So as long as you don’t put your eye, your hand, or your leg or something into the beam, you’re safe.

IRA FLATOW: Why is this such a rare event?

DEAN REGAS: Well, to get everything just lined up perfectly is pretty tough. I mean, Mercury from us is pretty far. It’s about 60 million miles from us and then it’s another 36 million miles from the sun. And it’s so small it has to just line up perfectly for all three of our bodies to be just so. And so it goes in these seasons. You can have a transit of Mercury around May 9th, or in November right around November 10th or November 11th. Those are the transit seasons where it crosses the nodes. It’s kind of like an eclipse, like eclipses are rare for the same reason. But these are even more rare.

A couple years ago, we had a transit of Venus. And those are boy, we get two of those every 100 years. And so Mercury is a least a little more often. We get about 13 to 14 every century.

IRA FLATOW: So this is not really terribly scientific, just a really cool thing to watch.

DEAN REGAS: Well, exactly. And this is one of those things that for me, this is what makes science so cool, is that if you’re out there you’re walking around normally, you would not notice anything different. The sun will be the same, the light will be the same, nothing will be happening. But we’re so smart that we can actually time this stuff, that we know exactly when Mercury is going to go across the sun. And with just a little bit of equipment, you can kind of see this.

And I’m very excited because the last one was 10 years ago, and I got clouded out. So I’m hoping, fingers are crossed that this one is going to be good.

IRA FLATOW: I know, we have a lot of bad weather here in the east and we’re hoping we get to see it also. Is this something that ancient astronomers were able to see? Did they write about this?

DEAN REGAS: Well this is a relatively new understanding, because the first transit Mercury that was ever seen was in 1631. An astronomer named Pierre Gassendi saw it just the year before, he read this book by Kepler that said OK everybody, look at the sun on this day in 1631. You might see Mercury go in front of it. Kepler had since died before that. So he never got to see it himself, but Gassendi did, and this was huge back then, because nobody could predict things that accurately. And Kepler’s tables were by far the best. This proved that his view of the universe was right. That everything went around the sun, and everything went around ellipses, and we can now predict things with such great accuracy.

IRA FLATOW: And it sort of is a down to earth so-to-speak demonstration of how exoplanet hunters look for planets, right? This is basically the same thing.

DEAN REGAS: Yeah, there’s that spacecraft called the Kepler spacecraft, another Kepler here, we’ll throw that in. This is looking at stars and looking for planets crossing from other stars. So it’s like they’re looking for transits of Mercury, except there are other stars. And when this went up, I thought, are you kidding me? I mean, we hardly have transits here. We have them very rarely. Are we going to find planets transiting stars? And I’m happy to say we found over 1,000 of them this way. We’re looking at other stars we could see, Jupiter sized planets going in front of another star, Neptune sized planets, and now we’re seeing even Earth and Mars sized planets going in front of other stars.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of Mars, what other planets are up now that would be worth going out to see?

DEAN REGAS: Oh well, we’re in Jupiter season right now. So that’s the star-like thing you see up at nighttime that’s really, really bright. I mean, it’s like suspiciously bright.

IRA FLATOW: I saw it near the moon the other day. It was really close.

DEAN REGAS: Oh, that’s the best. And that’s when we get our calls at the Cincinnati Observatory. They say, what was that thing next to the moon? Oh my gosh! And we’re like, oh, it was Jupiter. And they’re like, OK, that’s still cool. And then so in the next couple weeks, once we get into June, we get Mars season coming where Mars will be at its best. We celebrate, we call it Mars-a-palooza when that happens.

IRA FLATOW: What day would that be?

DEAN REGAS: It’s end of May, and then we have our Mars-a-palooza celebration and that’s going to be June 11th. That’s when you pick a Saturday night when I think the moon will be next to. We got it all set up.

Because people go really crazy about Mars. We’ve had events at the Observatory back in 2003 when Mars was at its closest, we had about 1,500 people showed up. We had lines down the street, people wanting to look through the telescope at Mars, and look for martians or something, I don’t know.

IRA FLATOW: War of the Worlds time, you know?

DEAN REGAS: Oh, I know people love Mars. It’s one of those things. I think it’s in our psyche. We want to know a lot more about it. So that will be in June, and then we have Saturn coming up too, which its rings are going to be tilted more towards us. So we’re going to see that picturesque picture of Saturn in the telescopes coming up.

IRA FLATOW: I’m going to have to pull out my 30-year-old Celestron and see if I can see it.

DEAN REGAS: Oh, that’ll work, that’ll work.

IRA FLATOW: And any meteor showers coming up?

DEAN REGAS: Well, we’re in the midst of one right now, actually. We had one that peaked this morning/until tomorrow morning. It’s called the Eta Aquarid. It’s not one of the most popular ones, but these are meteors that originated from Halley’s comet. The comet went by, it left parts of its tail behind, and now the Earth is running into it. So I had a few friends that stayed up last night and this morning, they saw some really good ones.

IRA FLATOW: Oh really?

DEAN REGAS: Yeah, they saw some really bright fireballs. One friend of mine even saw one that was so bright it casted a shadow.

IRA FLATOW: No, come on.

DEAN REGAS: I know.

IRA FLATOW: Was there any imbibing going on?

DEAN REGAS: I’m not sure, I need to talk to him, but I’m just doing my hearsay. And I’m a notoriously bad meteor watcher. Whenever I go out, they’re always never good. They’re never good. I mean, the reports are saying you can see 30 to 50 an hour shooting across the sky. Best time is between like 2:00 and 3:00 AM, but I kind of laugh at those numbers. Because whenever I go look at meteor showers, I see two or three and that’s it, hopefully. But one of these days, I might get lucky and get to see a real good one.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. What’s it called? The Eta?

DEAN REGAS: Eta Aquarids. So they look like they radiate out of the constellation Aquarius.

IRA FLATOW: Bits of Halley’s comet? Left over from Halley’s comet.

DEAN REGAS: Exactly. Yeah, so you get to see parts of Halley’s comet, since we won’t see the big body of it until 2061. So we get to see the little left over parts.

IRA FLATOW: When somebody points to the sky and says, hey look, at Halley’s comet, trying to distract you. It really will be.

DEAN REGAS: Well, that’s a good one. I’ll have to use that. That’s a good one, Ira. I like that.

IRA FLATOW: Can’t remember what movie that’s from. If you can’t get your solar viewer, if you can’t get out there to see the sun and get your viewer working on your own, you can watch it online, right?

DEAN REGAS: Yes, most definitely. Yeah, there’s going to be a lot of live streaming of the event. I know Sky and Telescope magazine is going to be doing one. And so this is pretty exciting stuff. And we’re really taking this one on. This is our practice. This transit is our practice for what I’m calling the big one on August 21st next year, 2017. We have the total solar eclipse. Oh my gosh. I’ve been waiting for this for since I started teaching astronomy 18 years ago.

IRA FLATOW: My daughter said five years ago, we’re going to see this one.

DEAN REGAS: Oh, it’s only a year away.

IRA FLATOW: Where do you go? I mean, you need to find someplace where you’re pretty sure there are going to be no clouds that day, right?

DEAN REGAS: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Where’s a good spot?

DEAN REGAS: Well, you can be anywhere on the strip of land between Oregon and South Carolina for that Eclipse. But the best weather forecast is Wyoming, Nebraska. The longest period of the eclipse is going to be in Kentucky. So as long as you find a clear spot, it’s going to be pretty much the same. I’m planning on going to St. Louis, watching the weather and driving east or west depending on what the forecast is. That’s my plan.

IRA FLATOW: You could maybe outrun a storm or some clouds or something.

DEAN REGAS: Exactly. I’m a certified eclipse chaser, Ira. I’ve had success the last four lunar eclipses, I caught all four of them. All of them I had to chase because of clouds. And I just barely made this one. Oh my gosh, it was close.

IRA FLATOW: Now, we’re going to talk more about this one.

DEAN REGAS: It is the big one, because it’s an All-American eclipse. And I think we’re going to have a lot of people seeing it.

IRA FLATOW: And you could just pull off the highway and sit there, right? You don’t have to go to any special place.

DEAN REGAS: Exactly, exactly. And it’s not like it’s an all day event. You just be in the right place at the right time for, I think the maximum eclipse is going to be two minutes and 31 seconds. You get there, that two minutes and 31 seconds will change your life. That’s for sure. I’ve seen one, and it’s great.

IRA FLATOW: Sign me up. All right, Dean. Thanks a lot.

DEAN REGAS: We’ll meet in Kentucky, how about that?

IRA FLATOW: OK. I’m on for this one. Dean Regas, outreach astronomer at the Cincinatti Observatory, co-host of a PBS program Star Gazers. Thank you, Dean.

DEAN REGAS: My pleasure. Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: We’ll see you next year, if not before.

DEAN REGAS: Keep looking up.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.