Most Powerful Neutrino Ever Is Detected In the Mediterranean

12:14 minutes

Neutrinos are sometimes called “ghost particles,” because they are nearly weightless, rarely interact with any other matter, and have very little electric charge.

Now, scientists have discovered a neutrino with a recording-breaking level of energy, which could bring us closer to understanding physics underpinning the creation of the universe.

Host Ira Flatow is joined by Sophie Bushwick, senior news editor at New Scientist, to talk more about the latest in neutrino research and other top science news of the week, including supersonic spaceflight without a sonic boom; an asteroid headed for Earth; and why loggerhead turtles are dancing.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman.

IRA FLATOW: And I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, a journey to the icy ends of the Earth to learn about science at the poles, plus what baboons can teach us about friendship between men and women. And in celebration of Valentine’s Day, we’ll share some of your science-centric love stories. You’re going to want to hear those.

But first, some new insights into neutrinos. They’re sometimes called ghost particles because they are nearly weightless, rarely interact with any other matter, and have very little electric charge– spooky stuff. Well, now, adding to the intrigue, the discovery of a neutrino with a record-breaking level of energy. Yes, joining me to tell us more about that story and other science stories of the week is Sophie Bushwick, senior news editor at New Scientist, based in New York. Welcome back, Sophie. Always good to have you.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: All right, start us off with the ABCs of a neutrino. What exactly is it?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So a neutrino is a fundamental particle. But instead of linking up with other particles to form an atom, for instance, a neutrino really very, very rarely interacts with regular matter. And to catch a glimpse of it, researchers build these huge detectors filled with a dense substance, like water. Or sometimes they use ice.

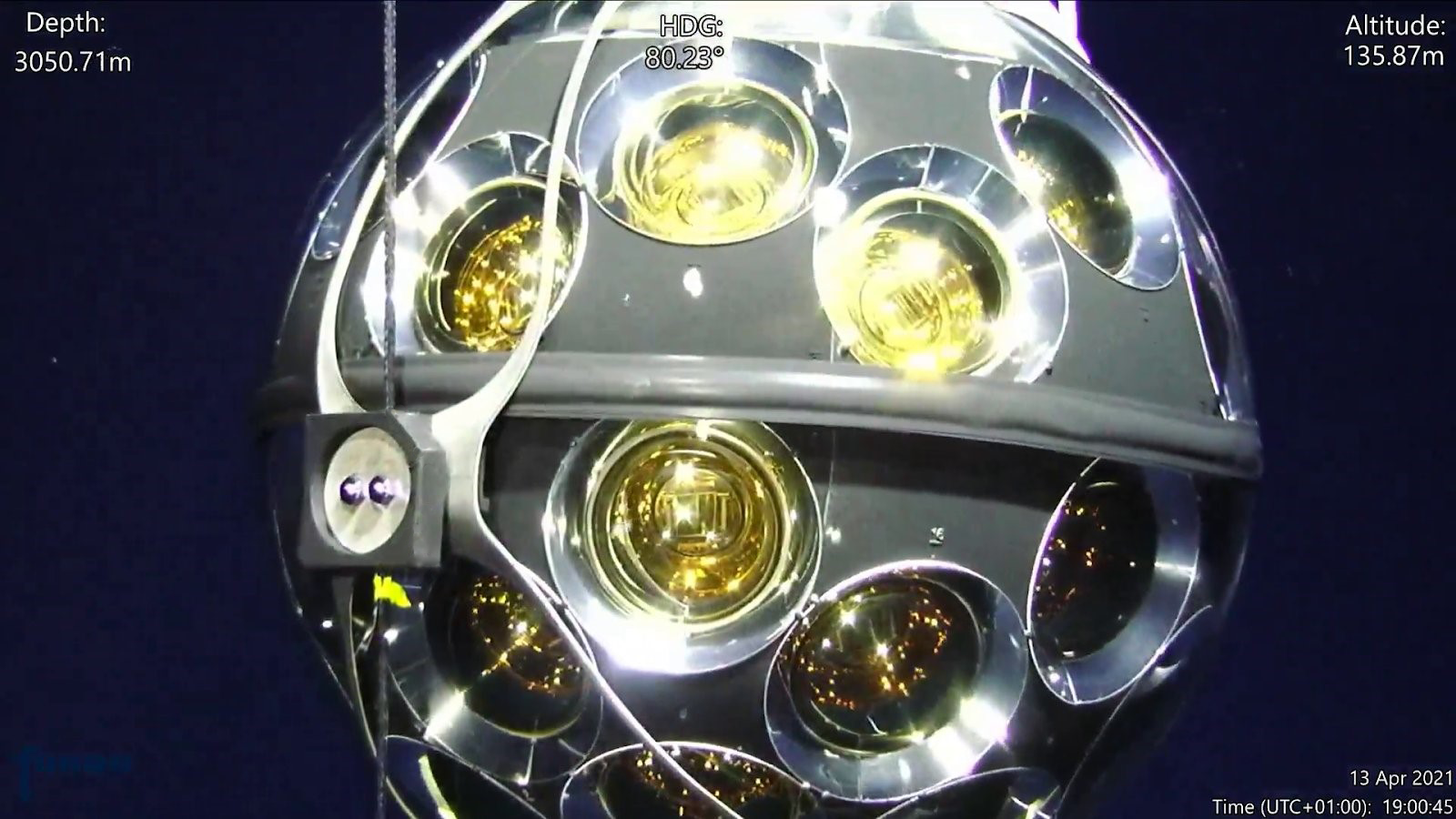

And the idea is on the off chance a stray neutrino might pass through this detector, it could bump into an atom in the water or the ice. And that could make a reaction of other particles that the detector is able to pick up. So you have these really big detectors in places like Antarctica and now one in the Mediterranean Sea, this relatively new detector that found a very powerful neutrino. It’s about 10 times more energy than the other, the previous record holder, which was found by the Antarctic detector.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It’s 120 peta electron volts.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s a lot, I’m guessing.

[LAUGHTER]

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I mean, on a larger scale, it’s not a ton. But when we’re talking about the particle scale, that’s big. That is thousands of times more energetic than the particles you would get at a particle collider, like the one at CERN.

IRA FLATOW: So what does this tell us about neutrinos that we don’t already know or teach us about the universe, or something?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yes. So the thing about a neutrino this powerful is it probably originated in a cataclysmic event somewhere out in the universe. Think it’s two supermassive black holes merging together, some event like that.

But because neutrinos interact so rarely with other matter, it probably traveled to us fairly directly from the event that spawned it. Which means we can trace it back much more easily than we can trace other kinds of cosmic rays that have a stronger electric charge, and so interact with other matter more. So that makes this a really cool option for us to observe the rest of the universe.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, neutrinos are really cool. Let’s move on to your next story about the changing shape of the Earth’s inner core. Really?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right. So Earth is sort of like we’ve got the crust on the outside. Then we’ve got a layer called the mantle. Then we’ve got the liquid outer core and then the mostly solid inner core. And we know that the liquid outer core, because of convection, is always interacting with the inner core. And this can change the way the inner core rotates.

But in a new study, they used seismic waves that were passing through the Earth. And they found that they changed in such a way that indicates that the inner core might not just be rotating. It could also be changing its shape.

IRA FLATOW: So, well, we know that the inner core may have slowed down over time, and now it’s changing its shape.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right. These changes in rotation, it means the inner core moves at a pace that isn’t always exactly aligned with the pace that the rest of the planet is rotating. And that actually makes it pretty hard to observe. Because you’ve got to account for that rotation when you’re trying to measure what else the inner core is up to. And that’s what makes this finding so interesting, that they’ve also managed to find these signs that it could be changing shape.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm, well, maybe it has something to do with my day feeling a little bit different in time.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: [LAUGHS] The inner core is messing with everyone’s sense of time.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to the next story. As we’ve seen throughout COVID, remember, wastewater surveillance has proven to be a really effective way to detect the spread of disease. And now a new study has found an even more efficient way to use this technology? Tell us about that.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right. So if you have a wastewater detection system at one site, you can monitor the waste from humans and see, what are the levels of different bacteria and viruses in these samples? So that will tell you if, say, COVID is going up in one place.

But what if you wanted to create a worldwide monitoring network to give you a heads up when an outbreak isn’t just happening in one place, but it’s creating a larger issue, like possibly even a future pandemic? You would think you might have to have monitoring sites at thousands of places around the world. But it turns out if you have just 20 airports all around the world, that’s enough to create a global monitoring system that can give you a heads up about disease outbreaks.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. And that would be a good place to put the monitoring devices, right?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yes, exactly. So when you fly on a plane, humans produce waste. The plane stores that waste. And then when you get to the airport, a truck comes and empties it off the plane. So that means that airports are getting these samples of humans from all over the place. And that makes it a really good place to take samples like this.

IRA FLATOW: With the US withdrawing from the World Health organization, I wonder if we would even be part of something like that.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That is the problem with withdrawing from global organizations like this. I mean, as we all learned from COVID, disease outbreaks don’t respect borders. And so in order to prepare for them, you really can’t just be focusing surveillance on one country or one location. It’s got to be a much bigger look.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, let’s stay with air travel for a bit longer. Because there’s an experimental aircraft, the XB1, created by the company Boom Supersonic. It hit supersonic speed, but without creating a sonic boom when it broke the sound barrier. Tell us about that.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yeah, Boom Supersonic might need to change its name. So this aircraft took advantage of a phenomenon known as the Mach cutoff. Basically, when you’re at different altitudes, the speed of sound is actually different. It moves more slowly when you’re at a higher altitude.

And if you’re at just the right altitude, and the aircraft breaks the sound barrier by just the right amount, the sonic boom is going to travel away from the aircraft in all directions. But as it goes downward, the speed of sound changes. And those changes actually deflect the sonic boom. So it still creates a boom, but that boom cannot reach the ground, which means you don’t get any of those effects like very loud, disruptive sound or breaking glass or shaking buildings on the ground.

IRA FLATOW: How soon might we see something like this in production?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Well, Boom Supersonic wants to use what it learned from its experimental aircraft and put that on a commercial airliner that it is planning to start testing in a few years. And they say that this could travel overland. So it could do, for instance, a flight from New York to Los Angeles without bothering the people on the ground below. And that would shorten that trip, for instance, by about 90 minutes.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s stay up in the sky a minute. Because there’s this story that’s been circulating about a big asteroid heading toward us with a pretty high collision risk. Is that true? Fill us in on that.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That is true. This asteroid has the not great name of 2024 YR4. And it has a 1 in 43 chance of hitting the Earth in 2032. So that’s not a super high chance, but it’s much higher than I’m really comfortable with.

And so the reason that it’s still uncertain, though, is because we’re basing those odds on data that’s incomplete. Errors can work their way in. So we really don’t know what the final odds will be until this thing gets a little bit closer.

But already that number is high enough, and the asteroid is large enough, that international bodies are starting to prepare for, what can we do if it does turn out that this is headed towards Earth? So, for example, NASA, a couple years ago, did a test where they deflected an asteroid. They got it to change its trajectory slightly. And so that’s the kind of mission that maybe will be necessary.

IRA FLATOW: This is not an Earth-destroying asteroid, like the dinosaurs.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right. Or you could also compare it to the Chelyabinsk meteor, which hit Russia in 2013. That was about 20 meters across. This one is going to be about twice that size or more. Again, there’s a lot of uncertainty. If it were to hit Earth, it would absolutely cause damage, but it wouldn’t be an extinction level asteroid like the one that knocked the dinosaurs out.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Let’s stay in space just a little bit longer to talk about scientists discovering the largest object in the universe.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. What is it?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It is called the Quipu superstructure. And it is 1.4 billion, with a B, light years long and hundreds of thousands of times more massive than just a single galaxy. So sometimes, galaxies clumped together in space into these clusters. And then sometimes, galaxy clusters clump together into what are called super clusters. And so some of these super clusters have previously been considered the largest objects in the universe. But the Quipu superstructure is the biggest found so far.

IRA FLATOW: Just as they used to ask Johnny Carson, just how big is it.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: [LAUGHS] So it’s got about 70 superclusters, all contained within this larger super cluster. And if you wanted to start at one end and travel to the other, even if you were moving at light speed, it would take you 1.4 billion years to traverse the whole thing.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow, that is pretty big. Let’s close on a delightful story about, of all things, dancing turtles, Sophie. Why are the turtles dancing?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: The turtles are dancing. And I would encourage everyone to look up a video of this because they are super cute when they dance. The turtles are dancing because they’re about to get =. And so they’re waggling their fins, their front fins. And they’re also sometimes spinning in circles, and they’re opening their mouths.

But the way that they know they’re going to get fed is what’s interesting here. So we know that turtles are really good at navigating through the ocean. And we think that they do so by detecting magnetic fields. And to learn more about that, researchers trained captive turtles that when they were in a certain kind of magnetic field, they would be fed. And just the turtles learned this so well that they started doing their anticipatory food dance as soon as they got to that magnetic field.

IRA FLATOW: So we learn a little bit more about how turtles navigate using magnetic fields, then.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s right. So for instance, they created a magnetic field that reproduces the field found in one of the migration areas for loggerhead turtles. And so they wanted to see if the turtles would turn in this magnetic field the same way that they turn when they’re out in the ocean. And they did.

And they also figured out, by testing different kinds of magnetic fields and how the turtles responded to them, they think now that there are two different ways that turtles sense magnetic fields. They use one sense to locate themselves on a map of the ocean or an internal idea of where they are. And the other one, they use to tell them which direction to go once they get to that place.

IRA FLATOW: Well, there you have it. Always great stuff, Sophie. Thank you for lightning our day today.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Sophie Bushwick, senior news editor at New Scientist, based in New York. If you want to see those dancing turtles, we’ve got a link for you, a video of the dancing turtles up on our website, sciencefriday.com.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.