The Global Pollinating Forces Behind Your Food

15:56 minutes

This story is a part of our spring Book Club conversation about ‘Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food.’ Want to participate? Join our new online community space or record a voice message on the Science Friday VoxPop app. And join us on Zoom on May 4 for a conversation about Indigenous food systems and the push to revive them.

Importing food from one country to another also means importing the resources that went into growing that food: Nutrients. Water. Sunlight. Human labor. And the labor of the bees, butterflies, or other insects and animals that provide pollination in that country’s ecosystems. Take Brazil, for example—Europe and the United States consume a large proportion of the country’s pollinator-dependent crops, from soybeans to mangoes, avocados, and other fruits.

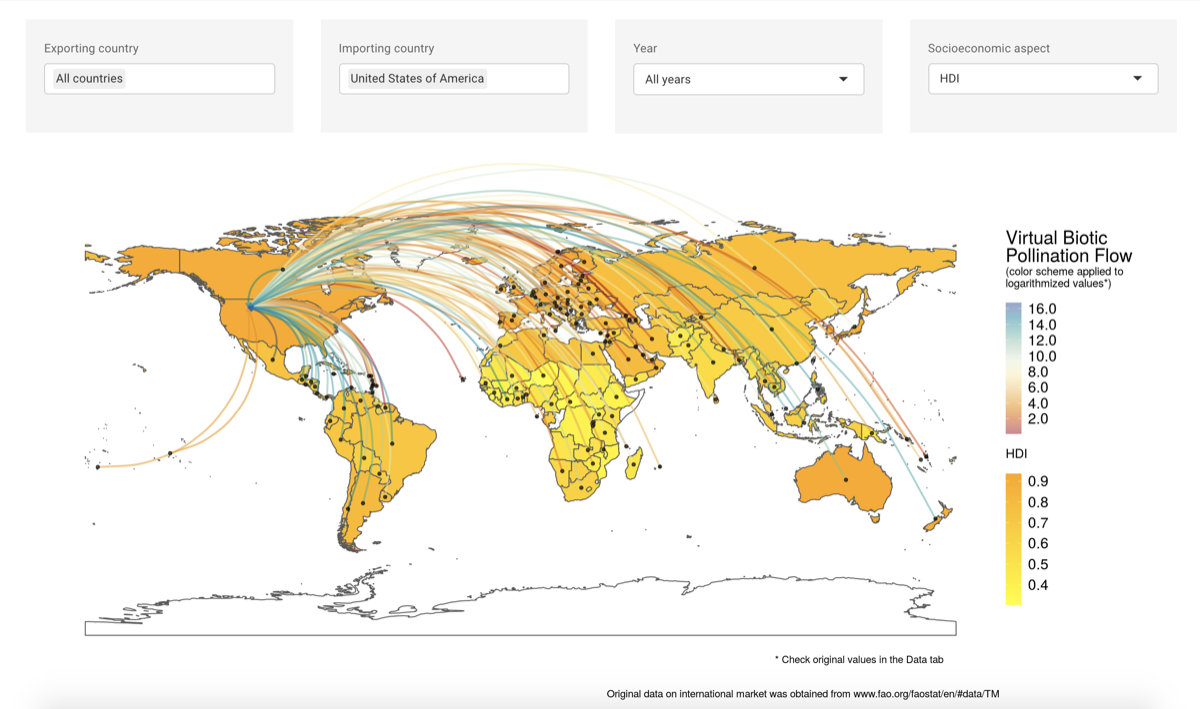

Writing in the scientific journal Science Advances in March, an interdisciplinary team of Brazilian researchers describe a way to quantify and visualize this flow of pollinator effort, from one country to another. They created an interactive web tool that lets anyone see this pollinator flow, for a specific country or a group of countries.

Importantly, the researchers say, the model makes it clear that this flow occurs mostly from poor countries to rich ones—with economic and ecological consequences for the poorer countries. Farmers, for example, may clear more land to grow crops for export, removing valuable pollinator habitat in the process. Those same farmers might then see their yields drop as pollinators die off, thanks to loss of habitat.

Producer Christie Taylor talks to two members of the research team, economist Felipe Deodato da Silva e Silva, and ecologist Luisa Carvalheiro, about the importance of considering pollinators in global food trade, and how better informed policy and consumer choices might help preserve threatened biodiversity.

This segment is part of our spring SciFri Book Club. For another culinary exploration, join us in reading Lenore Newman’s Lost Feast: Culinary Extinction and the Future of Food.

Luisa Carvalheiro is an ecologist and researcher at the Federal University of Goiás in Goiânia, Brazil.

Felipe Deodato da Silva e Silva is an economist and researcher at the Federal University of Matto Grosso in Cuiabá, Brazil.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. Take a minute to think about a really good breakfast you had recently. Maybe you started your day with coffee, treated yourself to some avocado with your scrambled eggs, and ooh, how about that orange juice? Well, producer Christie Taylor is here with some news about those avocados, those oranges, and those coffee beans. Hey, Christie.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Hey there, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So tell me what’s up with the orange juice.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Well, John, I really just want us to stop and think about how interconnected we are with ecosystems around the world. So if you’re in the United States like you and I are, one country that may have produced all those plants you just mentioned is Brazil. And those plants didn’t just grow in Brazil. They didn’t just soak up the sun and the water and the nutrients in Brazil. They were pollinated there, whether that’s by a domesticated honeybee or one of thousands of species of wild pollinators. So really, when you think about it, what’s moving from Brazil to the US isn’t just your avocado or your coffee beans, but the work done by pollinators.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Which makes total sense, that global food web is dependent on every aspect of the ecosystems where the food’s grown.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Right, exactly. And maybe, John, you’re someone who goes for the organic label with this kind of general idea that that’s better for biodiversity. But when you’re in the grocery store, John– be honest– do you think about the bees and butterflies and other pollinating animals in Brazil?

JOHN DANKOSKY: I have to be honest with you. I probably don’t. I think that it’s coming from Brazil, but I don’t think about all the work that goes into it, especially the work that those pollinators do.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Yeah, I’ll fess up– I also really don’t think about this. The organic label itself doesn’t even necessarily help pollinators if, say, a farmer is clearing forest– and pollinator habitats with it– in order to grow more of that food that I’m buying, which is why a team of researchers in Brazil started a project to help visualize this global interdependence and raise some awareness around it.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, this is good, because now I am thinking about it. And I don’t know. I want to learn more.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Sure. Well, I talked to two researchers in Brazil on this team, Dr. Felipe Deodato da Silva e Silva– he’s an economist and researcher at the Federal University of Mato Grosso– and Dr. Luisa Carvalheiro, an ecologist and researcher at the Federal University of Goias. They helped create this really, really cool tool which is visualizing this global flow of pollinator effort– they call it the virtual pollination flow– where you can basically plug in any country and see where the work that their pollinators are doing actually ends up. So here’s Luisa explaining the project.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: It’s a way to measure how natural resources are used in products that are exported that go to international market. That concept exists for water and soil, so what we wanted is to find a way of quantifying the contribution of biodiversity. And I think that’s the real beauty, and that’s why when Felipe proposed this as a way to bring pollinators to these metrics that are commonly used in economy, I thought it was really a nice way to quantify the contribution of biodiversity.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So you’re basically visualizing the way the work that pollinators do. So a bee or a midge collects the pollen in Brazil, but then the food that comes of that work ends up in a very different country a lot of the time.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: Exactly. So it helps to quantify it. There are other ways of quantifying the value of pollinators, but locally, so how much they contribute for production for the local economy. And now we are seeing the contribution to the international market.

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: The other aspect of this concept of virtual flow is that the national price don’t include those environmental costs. You don’t pay for the work of the bees. When we highlight this importance, we saw that international market is kind of neglecting these environmental costs, the importance of this service and other resources and other biodiversity services. So this is a very important socioeconomic issue.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: You know, we’re not just talking about the big commercial honeybee industry when we talk about these pollinators. There are all these native pollinators.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: Yes. Just when we think of bees, there are 20,000 species of bees in the world. And the managed honeybees are a bit more than a handful of species.

There are certain crops that are not properly pollinated by these managed pollinators. For many crop species, they are not sufficient. There are not enough. And they are not efficient in pollinating.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Felipe, when you look at this model, this virtual pollination flow, is there a pattern that becomes more clear, or is there just something about it that gets you really feeling like there’s a lot of possibility?

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: We know that developing country exports to richer nations. But why those country are not working together to protect pollinators? We know that there is a lot of national policies– for example, in the United States, in Europe– but the national policy is very scarce in developing country. International governance must be done. I think when we look at global scale analysis, we can see how much pollinator is important for consumption. And we saw the importance that maybe are being neglected by politicians.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: The concern about decline of pollinators– it started a long time ago, and it’s been increasing. Pollinators are just one of the essential functions that we need to be able to ensure that future generations will have quality of life. So it’s not the only, but it’s certainly an interesting function to focus because people can link it directly to their daily lives. It would be nice that more attention is paid to these type of functions, and that will probably lead to more protection of biodiversity overall.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Speaking of everyday life, when I think of pollinator-dependent foods that I eat, especially ones that might be imported from another country, I think of fruits and vegetables. What are some of the other crops that people maybe are consuming in rich countries– without thinking, possibly– that are really dependent on pollinators?

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: Coffee. Coffee is a good example.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I am drinking mine right now.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: Exactly. So it’s part of our daily lives of many, many people. But also, there are others that are a bit less obvious, like for example, the oils that we use for cooking and producing so many products. Sunflower is dependent on pollinators. Palm oil is dependent on pollinators. These are basic ingredients for the production of many other products that we consume, not only for eating, but also for other products. And they are dependent on pollinators.

Another example that might be interesting is cotton. What we know as cotton is the seeds. It’s the fruit. Cotton is pollinator dependent and obviously is very important for industry.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Felipe, as you mentioned, this flow from poor countries to rich countries– how does this affect the poor countries to be sending so much of the work of pollinators abroad?

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: I will focus on socioeconomic aspects. For example, if you dedicate a lot of cropland for international markets, you are restricting areas for national consumption. But if you export more vegetable or fruit from developing country, the national consumption has less food. The consequence for food security is that those products would be more expensive. For example, if you export a lot of rice, sugar cane, or, for example, common bean– common bean is a good example for this– the price here is very expensive.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Luisa, are there other ecological consequences, too, then?

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: There are some products that are 100% dependent on pollinators, but many others are partially dependent. So for example, you can have losses of 30% or 40%, but you will still produce. So when you lose the pollinators, you continue to produce on those lands, but you lose productivity.

And for a big farmer that relies a lot on exportation, he might be able to cope with that because he works in a very large scale. But the pollinators are being lost at landscape level, so many small-scale farmers are also affected. And they are not so capable of dealing with this loss of productivity. For certain crops, there might be ways of compensating, like renting hives or even hand pollination, but they are extremely expensive. So they are only accessible to large farmers, not to small-scale farmers.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Felipe, we have now then this tool. You talked about how it would be really great if there was more awareness and conversation around pollinators. Our listeners are in the US. If they’re trying to be kind to pollinators, does this mean they should be avoiding buying products from countries like Brazil, where this flow is really heavy, or is there another solution?

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: We are not against international trade. Avoid importation is not a solution here. We discussed that international trade, it should be more sustainable. For example, stimulating certifier products, organic products, international governments to transfer technology and financial resources to poorer countries that don’t have economic conditions to apply labor-friendly practice.

If you avoid the importation, international trade, poor countries will suffer, because they need money, you know? We argued that international markets should be more sustainable, and not stop the flow. We should make the flow more green.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: You mentioned earlier, we don’t pay the bees, or we don’t pay for the bees. If I could Venmo a bee for its work, or at least spend the money that represents the effort of the bees and other pollinators, would that help?

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: What market can do, what consumer can do, it’s more via prices and certification of products. And what government can do, maybe, is international government to transfer financial resources or technological resources to create conditions for poor nations, especially family farmers that Luisa mentioned, to apply those practice.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: So we’re talking about certifying products that have been created in a pollinator-friendly way, right? Not just saying, pollinators made this, but the farm on which it was grown uses pollinator-friendly practices.

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: Certified products– maybe we don’t need pollinator-friendly products. But for example, coffee– coffee’s a market where certification is well established. And the certification of coffee includes many environmental practice, and some of that benefits pollinators, you know? So I think that pollinators maybe is not a strong argumentation to make all those transformations, but would be a little step to discuss about the whole biodiversity, the whole nature. So I think the certification in general, certification that benefits conservation, biodiversity, would be sufficient to protect pollinators. I think we don’t need a specific certification for bees, you know.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: I think I just have one last question, which– Luisa, I’ll start with you– is just, what else do pollinators need? What do you think it will take to make sure we have pollinators well into the future?

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: So one thing that I think it’s important and that I think about a lot is that what makes sustainable practices go forward, it’s frequently economics and not so much the ethical part of the equation. So I think what moves the market– frequently, it’s the consumers that are looking for cheaper products. So those are the ones that will not buy a product that will be more expensive because it’s certified. And those have an important role in the market. And so they will influence the practices of the farmers.

There are already studies that show how farming can be more sustainable and profitable at the same time for the producers. And this needs more attention so that the information reaches the stakeholders, in this case the farmers, and that training is give to the farmers so that this can be more implemented in a more general way.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Just a quick reminder– I’m Christie Taylor, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Talking about the flow of pollinator effort around the globe. You had talked about this certification for biodiversity protection. Is there anything else that you hope might help incentivize the steps that are necessary to protect pollinators?

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: We are arguing the government intervention on this international problem that is the decline of pollinators, because farmers don’t know that they are benefited by pollinators. For example, some farmers– for example, the producers of coffee, cocoa, apples– they know that pollinator is very important, and they apply managed bees. But for example, soybean producers, common bean producers– they don’t know that pollinator is important. So the effort to governments make, politicians, to inform farmers of those benefits and to stimulate with economic instruments– I think that the huge difficulty here is how create international governance, how create international policies, that translate in local practice. And that local practice is appropriated to local contexts, so this is a very difficult task.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Felipe, Luisa, thank you both so much for your time today.

FELIPE DEODATO DA SILVA E SILVA: Thank you very much for your interest in our work.

LUISA CARVALHEIRO: Thank you for your attention, for all the curiosity about our project.

CHRISTIE TAYLOR: Dr. Felipe Deodato da Silva e Silva is an economist and researcher at the Federal University of Mato Grosso, and Dr. Luisa Carvalheiro is an ecologist and researcher at the Federal University of Goias, both in Brazil. I’m Christie Taylor.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.