Content warning: This interview includes discussion of miscarriage and pregnancy loss, and may be triggering for some listeners.

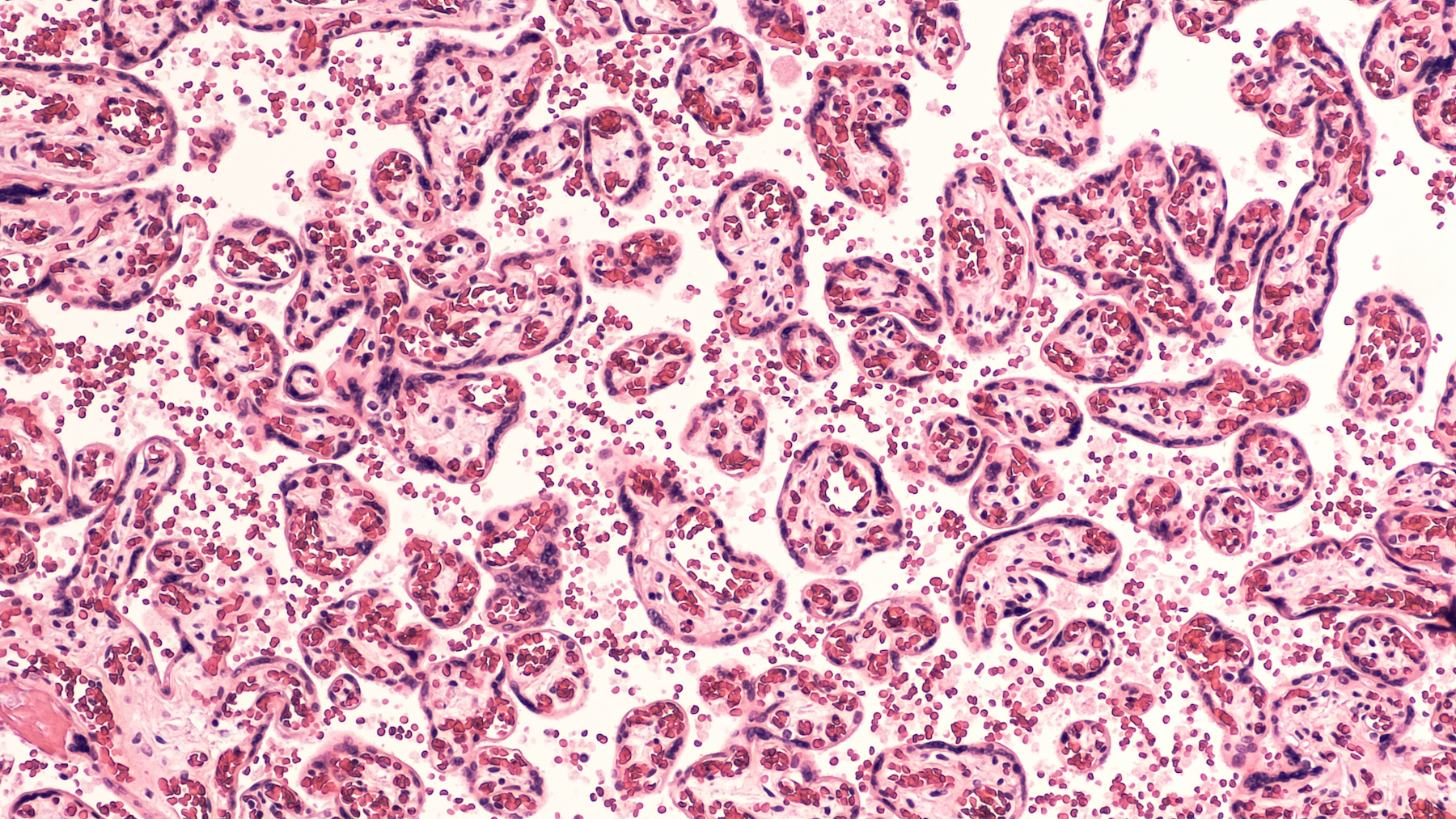

The placenta is an incredible body part. It’s the only organ grown temporarily, created during pregnancy and discarded after birth. It has the enormous job of supporting the growth of a fetus, protecting it from infection and inflammation. When something goes wrong with the placenta, it can result in the loss of a baby.

For something that can be so devastating to expectant parents, miscarriages are incredibly normal. Of the 5 million pregnancies each year in the United States, about 1 million end in miscarriage, categorized as a loss before 20 weeks of gestation. About 20,000 pregnancies end in stillbirth during the later stages of gestation.

Often, after a pregnancy loss, doctors tell parents that the cause is unexplained. This can lead to feelings of failure and guilt, even though pregnancy loss is almost always out of a person’s control.

Dr. Harvey Kliman, director of the Yale School of Medicine’s Reproductive and Placental Research Unit, has dedicated his career to better understanding the placenta and its relationship to pregnancy loss. Dr. Kliman and his team recently analyzed 1,256 placentas that resulted in pregnancy loss. They learned that 90% of these losses could be explained by conditions such as a small or misshapen placenta.

Dr. Kliman joins guest host Flora Lichtman to talk about his research, and the importance of studying the placenta as a way to better understand what leads to miscarriage and stillbirth.

Further Reading

- Read how Dr. Kliman helped one woman understand her recurrent pregnancy loss via Yale Medicine.

- Read about ongoing research and potential human trials for artificial wombs designed for extremely premature babies via MIT Technology Review.

Segment Guests

Dr. Harvey Kliman is director of the Yale School of Medicine Reproductive and Placental Research Unit in New Haven, Connecticut.

Segment Transcript

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. A heads-up, we’re talking about pregnancy loss. It’s a sensitive conversation. Please take care while listening.

The placenta is an amazing organ. It is the only organ grown temporarily. It shows up during pregnancy and makes its exit after birth. And it has a monumental job. It supports the growth of a new human being.

It provides the fetus with oxygen, food, and protects it from infection and inflammation. And if something goes wrong with the placenta, it can result in pregnancy loss. I know from my own experience a miscarriage can feel exceptionally devastating. But the experience is also completely ordinary. Roughly a quarter of all pregnancies end in loss.

And yet despite being so common, pregnancy loss can feel opaque. Doctors, mine included, often tell patients, sorry, we’ll never know why this happened. Just try again.

My next guest is working to change that. Dr. Harvey Kliman has dedicated his career to better understanding the placenta and its relationship to pregnancy loss. And lately, he’s made some breakthroughs. Dr. Kliman is a research scientist and Director of the Yale School of Medicine’s Reproductive and Placental Research Unit based in New Haven, Connecticut. Welcome to Science Friday.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Thank you so much for having me here, Flora.

FLORA LICHTMAN: OK, let’s start with the placenta. Tell me more about it. It seems like an amazing organ. But I want to hear more from you.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Sure. Well, I think one thing I want to clarify– people often say the baby is born and out comes mom’s placenta. The placenta is part of the baby, the fetus, and the embryo. You can think of the placenta as the root system of the tree. And just like a tree, a tree cannot survive without its roots.

As you said, at the beginning, it basically supplies everything necessary for survival. In fact, that embryo and fetus have no other way to survive except through the placenta. So if the placenta isn’t working or stops functioning, then that is disastrous for the embryo and the fetus.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wait, so are you saying that the placenta is not the pregnant person’s organ? It’s actually the fetus or the embryo’s organ?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Exactly. The mother, of course, has a relationship with the placenta. She is the one perfusing it, fountaining her blood into the placenta. But the placenta itself actually starts at day five after fertilization.

There’s something called a blastocyst. And at day five, there may be 10 cells that will become the embryo– the fetus and the baby. And the round part that makes up that ball basically is already the cells that will become the placenta.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s wild, because it means that the fetus is building its own support system. It feels like a lot for like an embryo or fetus to grow.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Absolutely, in fact, another way of looking at it is that you can think of the placenta as the boat that is carrying the embryo and the fetus on the journey. And the boat gets built first. In other words, before you go out in the ocean, you probably want to build the boat before you step on the deck, right? And so in essence, the way embryology works is the placenta is first. And it’s almost as if the embryo and the fetus are a passenger on the placenta.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Has the placenta gotten its due in the medical research community, in your opinion?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Oh, my god, no. It is so discarded. I mean, even the word afterbirth, right? And it’s– one of the challenges that we have is just simply even identifying placentas that should be examined after delivery. The 5 million pregnancies a year in our country, 4 million of them result in a normal outcome, a baby and everybody is happy.

But 1 million, that’s a big number. 1 million lead to pregnancy losses. And one of the questions is, which ones of those should be examined? You mentioned at the beginning that this is common. Yes, 20% to 25% of pregnancies, just based on the numbers I said, end in a pregnancy loss. There are sort of two responses.

Well, this is, you know, it happens and just try again, as you said. But what if it happens in the third trimester? That’s a devastating event. Basically, this baby is almost ready to be born and after 24 weeks can survive. And so I think we owe the people that are delivering these babies and answers to why something went wrong.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s talk about some of your work. In a recent study, you examined more than 1,200 placentas from pregnancy loss. What did you find?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Well, one of the reasons– just to back up a little bit on that question, which is an important question– is why we even did it. And the reason we were motivated to do it is that so many patients were sending me cases where they had no answer as to why they had a pregnancy loss. And they were very frustrated. They were frustrated with the response “just try again.”

Because a lot of people– in fact, virtually, all the people I talked to who are pregnant feel guilty that they must have done something wrong. So I think that having an answer, a scientific answer, as to why that pregnancy ended is very important for them, one, to realize that it’s extremely rare that they had anything to do with the loss, that this is a natural process and product of something that went wrong in the pregnancy internally and nothing to do with them, their uterus, what they ate, what they drank. So that was the initial motivation.

And when we looked at a series of losses starting from six weeks all the way to 43, we found that historically many of these losses were just categorized as unexplained and that seemed to be unfair for the patients who were having these losses. And so when we looked at the miscarriages– and let me just define what a miscarriage is. Right now in our country, we define it as a loss less than 20 weeks of gestation.

We found that the majority of those were due to some genetic developmental abnormality. Very few of them were due to things that people commonly think leads to these losses, like clotting disorders or immunologic problems. We did find some of those, but a very small percentage. The majority of the miscarriages were due to a genetic issue.

FLORA LICHTMAN: In the fetus or embryo.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Right. And, of course, we’re looking at the placenta. And based on what we just talked about, looking at the placenta is looking at the embryo and the fetus.

They’re the same thing, because genetically they’re the same. They’re part of the same system. So if I see abnormalities in the way that the placenta grows, then that’s basically saying there’s an abnormality in the whole pregnancy.

I’ll give an analogy. For example, I think when people buy Christmas trees, they like to see a nice symmetric Christmas tree and the leaves all even on both sides. If it’s very abnormal and misbalanced, people will say, well, I don’t know what’s wrong with that Christmas tree, but I don’t like it. And that’s something like what we do with the placenta. The placenta grows normally very symmetrically.

And when there’s a genetic abnormality, it grows with asymmetry. We call it dysmorphic features or abnormal development. And that was the majority of the cases. Up to 86% of those miscarriages had that abnormal growth pattern.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Wow.

HARVEY KLIMAN: In the stillbirths, which is a completely different group of cases– and one of the things that we also learned in our work is that the dividing line between less than 20 weeks and greater than 20 weeks is kind of artificial. It’s in the middle of the pregnancy of 40 weeks. But we think based on our data now that the dividing line should happen between the second and third trimester. So when you look at third trimester, and I’ll focus on that, the absolute number one cause of stillbirths in the third trimester is a small placenta. Over 36% are due to small placentas.

And then, the next most common category of loss relates to cord accidents, something like a knot in the cord, or a kink in the cord, or a rupture of a vessel in the cord. And the umbilical cord is like for the scuba diver the hose that goes between the tank and their mask. So if you’re underwater, and you might have enough oxygen in that tank, but if somebody crimps that hose between the tank and your mask, that will be very bad for you as a diver.

And that’s just what happens to the fetus. If something happens to that umbilical cord, that can be disastrous. And then, there’s a small percentage, about 16%, that are genetic still even in the third trimester. And then, there are series of causes and explanations that are much less, less than 5, 6, and things like that percent.

FLORA LICHTMAN: You know, it’s amazing because any pregnant person will tell you there’s a lot of monitoring that happens when you’re pregnant, especially towards the end. You’re in there for weekly scans. And it’s not a small amount of monitoring. So it’s interesting that there’s something else doctors could be looking for.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Well, I agree. And did people know that a small placenta is a potential problem for stillbirth? The answer is yes, absolutely. What hasn’t happened, though, is the next step, which is to add it to the routine prenatal care. And one of the problems when I first started working in this field in the 2000s when I had a series of cases specifically that were stillbirths due to small placentas, after about three of them in a row, I went to my maternal fetal medicine colleagues at Yale and said, hey, how come you’re not looking at the placenta?

And they said, well, it’s actually too difficult to do, because it’s this curved shape. It’s kind of a beanie cap on your head. And it’s difficult to measure it doing an ultrasound. Normal ultrasound measurements are lines from one point to another point, and you get a number, and that’s easy to do. Measuring the volume of a placenta is challenging.

But luckily, my father, who unfortunately has passed away, but at the time in the 2000, he was an electrical engineer and a mathematician. And I said, dad, do me a favor. I have this mathematical problem. If you cut a cross-section of a placenta and get this sort of sickle-shaped image, and I give you the width, the height, and the thickness, can you tell me the volume based on a mathematical equation?

So we created that equation for me. We tested it and showed that it worked very well. We call that estimated placental volume. And since that time, we’ve published a number of papers on this. And we’ve been trying to get it to be incorporated into clinical practice, but that is a big challenge because–

FLORA LICHTMAN: Why?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Why? Great question. The pushback is that they say, well– you know, I felt like Dorothy with the Wizard of Oz. So I went to the wizard, I said, you know, I’d like to go back to Kansas. Well, that’s fine, but you have to get the broomstick first.

And so in other words, every time I’ve gone to people and said, OK, I’m ready to show you this, they say, well, you have to do this one extra thing. So in the beginning, they said, well, you have to prove that the equation works. OK, we proved it. Well, now, you have to make normative curves to show us what is too big, too small, and what is normal. OK, I did that.

And then now, they’re saying, well, you have to prove that it prevents stillbirth. And that ask is very difficult. It’s actually very difficult to prove that something can prevent something that ends in a loss, right? Because if you do something and intervene and there is no loss, people can always say, well, we don’t know if there would have been a loss if you hadn’t intervened.

FLORA LICHTMAN: But what is the bigger reason why? These are the specifics of why it hasn’t gotten there. But it feels like there’s something else driving the roadblock, which is it like just institutional habits or what is it?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Wow, I wish I knew the answer to that. I think it’s a couple things. I think that number one, people aren’t trained to do it right now. Number two, it’s novel, so it’s not what people think about.

And again, I think the mental view when you think of a pregnancy is the fetus, the baby to be, that’s what the focus is on. And I have so many OBs and maternal fetal medicine colleagues who say, well, I follow the fetus, and that’s good enough, and that works for me. And 99% of the time, they’re right. Stillbirth is rare. It’s less than 1% of the time.

So people can do what they’re doing now without really perceiving that it’s an issue. But for the individual patient who has that stillbirth, and, for example, on their due date, they lose their child, and they find out that their child was in the 80th percentile, but their placenta was in the third or second percentile. And they realized that if somebody had just known that, they might have still had their child be alive right on the due date.

That’s pretty hard to take. So the loss– small placenta loss mothers who are my patients have created basically an army. And they are trying to change things, but it is very challenging.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Huh. I really– it’s hard to even imagine. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I’m talking with Dr. Harvey Kliman about pregnancy loss. Dr. Kliman, what causes a small placenta?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Well, that’s a great question. So the number one cause is intrinsic genetic issue. We don’t exactly know what is behind that. But our guess at this point is it has something to do with the heart. And you might think, well, how does the heart in the fetus relate to the size of the placenta?

But the way I think of it is like a bicycle pump. A bicycle pump blows air into the tire and makes it bigger. The fetal heart is actually pumping blood into the placenta. And although, we haven’t proven this, and we are doing studies right now to try to validate this concept, this hypothesis I’ll say. The hypothesis is that when the heart is not working perfectly and pumping out blood at high pressure in a normal way, then the placenta may not inflate as well.

FLORA LICHTMAN: If someone’s listening to this conversation, and they’ve experienced pregnancy loss, and they have questions about what happened, what do you recommend that person does?

HARVEY KLIMAN: Well, the first thing wherever they are in the world literally, the most important thing is to try if possible to have the loss tissues be looked at and sent to a local pathology department. Because at least then, even if the local people don’t know what to do with it or they simply say something like products of conception, that is a very common diagnosis, it doesn’t mean anything. It just says, yes, there is tissue that I’m looking at that represents a pregnancy, but there’s no answer by saying that diagnosis as to what actually happened.

But the good news is once it is processed and that tissue is put into wax blocks, those wax blocks are saved, at least at Yale and definitely in many places, 10 years. And so those recuts of those blocks, slides can be made of those and sent to someone who is specialized who can look at those slides and make a diagnosis.

We at Yale and other centers are doing a large study called Genomic Predictors of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss to actually do what’s called whole genomic sequencing, sequence all six billion– that’s with a B– DNA codes to see if we can actually find the genetic markers of these recurrent pregnancy losses. So that’s the next horizon with miscarriages to see if we can find the actual causes for these losses.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What drives you to do this work? I’m guessing it’s not about your firsthand lived experience. But you tell me.

HARVEY KLIMAN: Well, to start off, one, I’m a son of a radical feminist. My mother was– took me to Washington, had Ms. magazine, the first issue. So I grew up with that whole sort of milieu and a very strong support for women’s rights, and their freedoms, and their ability to do what they want to control their own body, of course. And let’s be honest, reproduction is the most amazing thing. To create a new life is a miracle. And it’s a pleasure to work on it and help couples figure out how to have successful pregnancies.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Dr. Harvey Kliman, research scientist and Director of the Yale School of Medicine’s Reproductive and Placental Research Unit based in New Haven, Connecticut.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Meet the Producers and Host

About Kathleen Davis

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

About Flora Lichtman

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.