PFAS Chemicals, And You

33:40 minutes

Este artículo está disponible en español. This story is available in Spanish.

Eighteen years ago, a lawyer named Robert Bilott sent a letter to the EPA, the attorney general, and other regulators, warning them about a chemical called PFOA, short for perfluorooctanoic acid.

Outside of the companies that made and used PFOA, most people had never heard of it. But E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, better known as DuPont, had been using PFOA to make Teflon since the early 1950s. In the course of a lawsuit against the chemical corporation, Bilott had uncovered a trove of internal company documents, showing DuPont had been quietly monitoring the chemical’s health risks for decades, studying laboratory animals and their own workers. Bilott called on regulators to investigate and take action.

PFOA has since been linked to testicular and kidney cancer, among other diseases. It is part of a larger class of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which have now been detected in everything from polar bears in Svalbard to fish in South Carolina, and are estimated to be in the blood of over 98% of Americans.

In the mid-2000s manufacturers started voluntarily phasing out PFOA and a related chemical, PFOS, but they substituted them with other PFAS chemicals, whose possible health effects are still being investigated and litigated.

Nearly two decades after Bilott wrote the EPA, the agency has not regulated these chemicals, but it says it plans to begin the process by the end of this year. Bilott, who previously secured a $670 million settlement from DuPont, is now suing DuPont, Chemours, and others on behalf of everyone in the United States who has PFAS in their blood.

This week, Robert Bilott tells Ira his story, now featured in his book, Exposure, and the movie, Dark Waters, out in theaters November 22. You can read an excerpt of Bilott’s book here.

Sharon Lerner of The Intercept also joins to discuss what is known about these chemicals, and what is and isn’t being done to limit our exposure.

We contacted DuPont, its spinoff Chemours, and 3M for comment. In a statement to Science Friday, DuPont said it “does not make these chemicals in question” and that it has “a series of commitments around our limited use of PFAS—which includes eliminating the use of all PFOA/PFOS-based firefighting foams from our sites.”

Note that PFOA and PFOS are just two chemicals within the broader class of PFAS, which includes hundreds or thousands of compounds Manufacturers have voluntarily phased them out in the United States.

DuPont also stated it grants “royalty-free licenses to those seeking to use our PFAS water treatment resin technologies.”

The DuPont spinoff Chemours, which inherited its Teflon line of products in 2015, has not responded to a request for comment. 3M declined to provide a statement, but directed us to materials about PFAS on their website.

See DuPont’s full statement below.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Robert Bilott is a partner at Taft, Stettinius & Hollister LLP in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Sharon Lerner is a health and environment reporter at The Intercept in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. In 1998, a lawyer, Robert Bilott, looking for evidence of chemical poisoning on farm animals sued the chemical company DuPont. And in the process, he uncovered a trove of internal documents about a chemical called PFOA. PFOA is part of a larger class of chemicals called PFAS, P-F-A-S. For decades, Robert has been suing chemical companies and fighting to get these chemicals regulated. In September, he testified before the House’s Oversight and Reform Committee.

ROBERT BILOTT: After years of litigation, to pull this information out and to make it public after gag orders, protective orders, et cetera. Now that this information’s finally there, unfortunately, EPA still has not acted. I first warned EPA 18 years ago, and we are still here.

IRA FLATOW: Robert Bilott is a partner of the law firm Taft, Stettinius, and Hollister in Cincinnati. He talked about it, as he said, for about two decades, he’s been on a crusade. And there’s a new book out about it called Exposure, and a new movie about this called Dark Waters based on his story comes out November 22. We invited DuPont to join us to talk about it. They have declined, but they have sent a statement over, which will read at the end of the segment. Welcome to Science Friday, Robert.

ROBERT BILOTT: Thank you so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Back in 1998, you were not in the business of suing chemical corporations, but defending them, right?

ROBERT BILOTT: That’s right. I started working for the law firm of Taft, Stettinius, and Hollister in 1990 in their environmental department, representing corporate clients, and a lot of those were big chemical companies.

IRA FLATOW: So what turned you to the other side?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, it was about eight years into that working at the firm. I got a call one day, and a gentleman on the other end of the line started talking about cows dying. And I wasn’t quite sure what he was talking about. I was about ready to hang up the phone. And he blurted out that he had gotten my name from my grandmother.

And it so happened that my grandmother and my mom’s family had grown up outside of Parkersburg, West Virginia. And this gentleman was calling from that same area. And so when I heard that he had gotten my name as a recommendation from my grandmother, I started listening and invited him to come up and show us what he had, what he was concerned about.

IRA FLATOW: And he was concerned about animals– farm animals– dying on his property?

ROBERT BILOTT: That’s right. He raised several hundred head of cattle on a piece of property outside of Parkersburg, West Virginia, right along the Ohio River. He and his family had been doing that for quite some time. And over the preceding couple of years, he had noticed all kinds of problems with his cows– tumors, they were wasting away, their teeth were turning black. By the time he called me, he had lost over 100 cows.

And he was also seeing impacts in the local wildlife. He was seeing deer dying, fish, birds, you name it. So he was convinced there was something in water that was running off of a nearby landfill that was impacting everything in the area.

IRA FLATOW: And you took the case to defend him and decided to look into it. And you did find evidence for the animals getting sick.

ROBERT BILOTT: That’s right. We ended up finding out that this landfill was owned by the DuPont company, which owned a huge manufacturing facility right up the river. And this landfill was where they’d been disposing waste for many years. And so when we took this case on, we started digging into what was permitted, what went into this landfill, what was allowed by the local government agencies, and really couldn’t find anything that was explaining what we were seeing in the animals. So I sort of broadened our request to the company for additional documents.

We ended up having to bring a lawsuit against the company, DuPont. And we finally started getting internal documents. And one day, I stumbled across a document that mentioned something called PFOA had been sent in materials to that landfill, something I’d never heard of. So that started me on a whole other journey.

IRA FLATOW: And so what did DuPont documents say about the health risks of PFOA?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, it was pretty disturbing, actually. I mean, I tried going to our environmental library at the time. This is back in 1999, the year 2000. I really couldn’t find anything about what this chemical was. I really wasn’t finding much in the published literature. There wasn’t much out there.

And so we started digging into the company’s own files. And what we saw was this was a completely man-made, synthetic chemical, had not existed on the planet prior to World War II, been invented by the 3M Company right after the war. And they were selling this material, PFOA, to DuPont, who was using it since as early as 1951 at this factory up the river. And it ended up– this was the world’s largest Teflon manufacturing site. And this chemical was being used by DuPont making Teflon.

Well, they’d been studying the health effects of the chemical since the ’50s, finding all kinds of problems– toxicity in rats and monkeys and dogs. And they had been studying the workers, and they even had been doing cancer studies and had found out by the ’80s that the chemical caused cancer in rats and even internally classified it as a confirmed carcinogen. But the most disturbing thing was we were seeing that the company had all these documents, but we didn’t really see where any of this information was being shared with the regulatory agencies or really was known outside the company.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. And so you settled that case for that farmer but then decided to expand it to a class action suit?

ROBERT BILOTT: That’s right. Yeah, one of the things we found was not only did we find out this chemical was in the landfill, we found out there were about 7,000 tons of sludge soaked with this chemical in the landfill. The chemical caused white foam. So when we figured out what was going on, we were able to settle the case for the farmer, Mr. Tennant, and his family.

But what we also discovered was it wasn’t just on the farm. DuPont had been sampling the drinking water supplies of the surrounding community and as early as 1984 had found that the chemical was in the public water supply. And even though it wasn’t regulated– the regulatory agencies didn’t know anything about it– DuPont had set its own drinking water guideline. And the levels in the water supply were above that.

So we realized we might be the only ones who knew that, because this was in the internal files, but the regulators, the public, didn’t know. So I sent a big letter to the EPA and to the state agencies in 2001 alerting them. And that’s the point where the public finally found out this was in their water.

IRA FLATOW: Mhm. And where does that suit stand now?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, we ended up, after several years of litigation and finding even more documents and finding more disturbing information about the chemical, we were able to settle that case in 2004. It was after EPA even sued DuPont for withholding information about the chemical from the agency. We were able to settle the case.

By that point, we found out that the chemical had made its way into the water of 70,000 people on the Ohio and West Virginia side. And we were able to get clean water filters put in. But most importantly, under that settlement, we set up a process to have independent scientists look at all of the data and confirm what kind of health effects were generated from exposure to the chemical. That took seven years.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow.

ROBERT BILOTT: And we had 70,000 people, actually, from the community that came forward, gave blood, participated that. And after seven years of some of the most comprehensive human health studies ever done on any chemical, that independent panel confirmed that drinking that chemical was linked with six diseases, including several forms of cancer.

So after that, those people were entitled to free medical monitoring under our settlement, and the people that had those diseases were able to bring individual claims against DuPont. We had about 3,500 people do that. And those started finally going to trial in 2015.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring on another guest. Sharon Lerner is a health and environment reporter at The Intercept. She’s been covering the PFOA and the larger class of PFAS chemicals for several years. Welcome to Science Friday.

SHARON LERNER: Hi, thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Incredible story, isn’t it?

SHARON LERNER: Yeah, it is. It is.

IRA FLATOW: And how widespread– you know, I mentioned that it’s in lots of different things. It’s in just about everything, right?

SHARON LERNER: Yeah, it is at this point, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Do we know what levels it’s dangerous, or?

SHARON LERNER: Well, that is being determined. And, you know, when I first learned about this story– I started writing about it a little more than four years ago– the numbers that I heard as safe were much higher than they are now. The EPA had, I believe it was, 0.4 and 0.2 or 400 and– it’s hard to– now we’re talking about parts per trillion.

IRA FLATOW: Right.

SHARON LERNER: So it was much higher, right? It was 400 and 200. Is that right, Rob?

ROBERT BILOTT: Correct.

SHARON LERNER: And now we’re at, as of 2016, the safety level that the EPA set was 70 parts per trillion. But you’ve seen several states set much lower levels. And then recently, Linda Birnbaum, who is the recently retired head of the NIEHS, which is the National Institutes for Environmental Health Sciences, she said that she thought a safe level should be around 0.1 parts per trillion based on research her agency did. So you’re seeing really a very downward slope, which is not unusual for environmental contaminants. As we learn more about them– this happened with lead, too– you see the numbers go down and down.

IRA FLATOW: Robert, are these chemicals– were they taken off the market? Are they still being used places?

ROBERT BILOTT: Yeah, the 3M Company actually announced in 2000 that they would stop making these chemicals. DuPont actually jumped in at that point and started making PFOA at its own plant down in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Well, after DuPont was sued by the EPA in 2004, they agreed to settle that case, and then right after, announced a phase-out of any further manufacturer of the chemical in the United States. But that was over the next 10 years.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

ROBERT BILOTT: And over that 10-year span– and Sharon has written some tremendous articles about this– additional chemicals that were deemed to be, quote, “safe replacements” were brought out onto the market. And we’re finding out that many of these may present some of the same problems as the ones that were phased out.

IRA FLATOW: I want to bring in our listening audience. 844-724-8255, 844-724-8255, or you can tweet us @scifri. Sharon, is it true that there are tens of thousands of chemicals?

SHARON LERNER: No.

IRA FLATOW: I saw the number 60,000–

SHARON LERNER: Well, no.

IRA FLATOW: –be quoted that are–

SHARON LERNER: No. In the class?

IRA FLATOW: Yes.

SHARON LERNER: No. The class is in the thousands. But I think it’s between 4,000 and 7,000 actual chemicals, PFAS chemicals. And so after– Rob was saying– 2015, basically, there was this voluntary phase-out. But this was– and we’ll get a little technical here– this was for the PFAS that were based on chains of eight carbons or longer.

And so then we had these short-chain PFAS replacements, which he mentioned. And these, because they weren’t subject to this voluntary withdrawal, start entering the market. And it turns out that, again, some of them pose some of the same health problems. The best-known one at this point is called GenX. And that’s DuPont’s replacement for PFOA, and that’s based on six carbons.

And, you know, we heard the name of it. I was able to find some documents that were actually on the EPA’s own website that DuPont had submitted to the agency that showed that GenX caused health problems, including cancer, in lab animals. So the EPA had those documents and went ahead and allowed them to make it anyway. And subsequently, we’ve learned that GenX is in the drinking water of some 250,000 people in North Carolina.

But this is the best-known one. There are actually many, it turns out. I recently wrote about 40 replacement PFAS chemicals that have posed similar problems– neurotoxicity, developmental toxicity. And these are all from reports that the manufacturers submitted to the EPA, that the EPA has, even while it’s allowed these chemicals to be used and made here in the US.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Talking about the PFAS family of chemicals with folks who should know. Our number, 844-724-8255. So where do we stand now? I mean, has the EPA decided or attempted to take these chemicals off the market? Or whose decision is that?

SHARON LERNER: No, they have not been subject to binding regulation yet. They have not been banned. As we said, the longer chain ones were subject to this voluntary withdrawal. The shorter ones, they seem to be– sometimes they are released onto the market with something called a consent order, which says, OK, you can only make X amount of it, and it puts other restrictions on it.

Unfortunately– and I’ve gotten some of these documents– the amount that, you know, that is capped and you can’t make more than that is confidential almost always. So it’s impossible to know if these arrangements are being adhered to or not.

IRA FLATOW: A quick tweet before we go to the break. Chris asks, “What are the myriad uses for this substance that makes it so difficult to phase out quickly?” Sharon, you want–

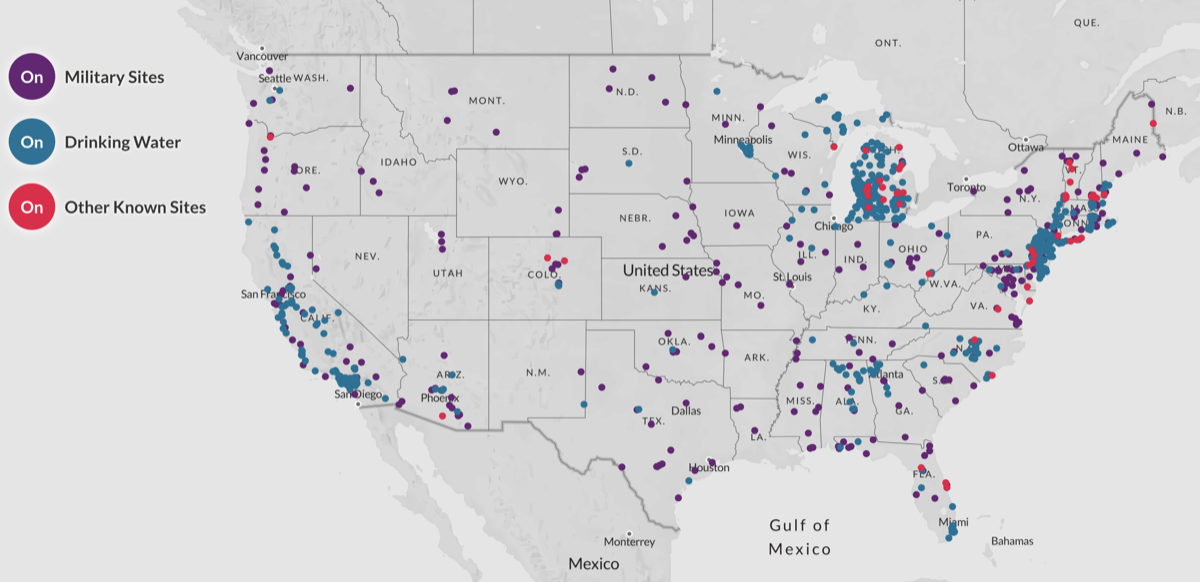

SHARON LERNER: Oh, there are so many. And Rob, you can chime in when I’m done with my list. There are nonstick coatings and stain-resistant coatings, like Scotchgard, right? You see them in firefighting foam, which means that the military is actually a huge source of pollution, because these– AFFF, it’s called– these firefighting foams that put out jet fuel fires have been used around the country, and from that use, have seeped into drinking water near military bases. So that’s another huge use. Many other industrial uses– Rob, do you have others?

ROBERT BILOTT: You know, I think that’s a great list. And the other thing to keep in mind is that because of all those uses, what we’re finding now is this chemical is showing up in drinking water all over the country. And not just in the US– now it’s all over the world. And it’s not only made its way into our drinking water, into our soil, but also into our blood. It’s now being found in human blood of virtually 98% or 99% of the people on the planet. So we’re talking about uses through all these different products that have really generated unprecedented exposures worldwide.

SHARON LERNER: And–

IRA FLATOW: Let me just announce that I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And we’re going to have to take a break. So I didn’t want you to get into– I know you’re going to jump in and say something. So we’ll get back and talk lots more with Robert Bilott and Sharon Lerner. Our number, 844-724-8255. Stay with us. I know you want to talk about this, so we’ll take your calls and talk some more about it after the break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about the ubiquitous and potentially hazardous PFAS chemicals. You may be exposed to them through food packaging, drinking water. They’re even found in breast milk.

My guests are Robert Bilott, a partner at Taft, currently suing on behalf of everybody in the US with PFAS in their blood. He is author of a new book, Exposure. Sharon Lerner, a reporter at The Intercept covering health and the environment. Our number, 844-724-8255. Lots of calls. Let’s see how many we can get in there. Claudia in Westchester, hi. Welcome to Science Friday.

CLAUDIA: Hi. Just really grateful you guys are doing this work. My question is, I studied environmental policy and science, and that was our curriculum for undergrad and master’s. And I was really surprised we only had to take one toxicology course and that even, you know, our professors were saying, like, there are thousands of chemicals that are being released into the product stream every day. A lot of them are not tested.

How are these products and chemicals even being, like, approved to be in products in the first place? Like, how can we prevent these kinds of things from happening instead of trying to deal with the mess afterwards after damage is already done?

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let me get an answer. Robert or Sharon, you want to take this? Robert, go.

ROBERT BILOTT: Sure.

IRA FLATOW: How do these chemicals get out there in the first place?

ROBERT BILOTT: Yeah, I mean, you have to take a– you have to look at it from the historic perspective here. These chemicals were, like I mentioned before, they came out right after World War II. And that’s decades before there even was a US EPA or before even some of the federal laws first started coming out to regulate chemicals.

You know, our first real, comprehensive federal law governing new chemicals coming out of the market, Toxic Substances Control Act, came out in 1976. That’s decades after these chemicals were already out and being used. And under that law, under that Toxic Substances Control Act law, it really focused on new chemicals coming out. And for things like PFOA that were already out there, it essentially required companies that were using or manufacturing those chemicals to notify the agency if they believed the chemical presented some sort of substantial risk.

So it was up to the company to really alert the agency and tell them whether there was a problem. And what we saw in the case of PFOA was the company just repeatedly making the decision. They didn’t think there was a problem, despite what was in their own records. So the agency didn’t know and had to catch up.

So because of that and similar situations that occurred over the last several decades, there was some change made to that law just recently in 2016 to try to beef up their requirements. But, you know, for communities that are exposed to chemicals like this, under our legal system, the people who are exposed are essentially told they’re the ones who have to come forward and prove that the chemical was causing them harm, and the company that put it out there doesn’t have to prove that it’s safe.

IRA FLATOW: It doesn’t? Sharon, is that–

SHARON LERNER: Right, yeah. There’s this presumption of innocence, basically, on behalf of the chemicals. It’s true. And then the other part of this is the numbers. So we’ve had this exponential growth in industrial chemicals. We have more than 40,000 in use right now on the active list. And so you see the EPA trying, with varying degrees of success, to try to assess their safety.

But they’re going so slowly, and there is so much pressure from industry. When they close in on a chemical and actually come close to regulating it, it slows down the process incredibly, and there’s virtually no hope of, you know, actually assessing the vast majority of them at this point.

ROBERT BILOTT: Yeah, I mean, if you look at the situation with PFOA, it’s a perfect example of that. You know, we first alerted the agency in 2001, 18 years ago, about what we were seeing, about the chemical, how people were being exposed, its toxicity. And then we ended up doing– the community had to come forward and do some of the most extensive human health studies ever done.

So we now have some of the most extensive, comprehensive data on a chemical like this, more so than probably any other chemical. Yet we are still dealing with a situation where the agency has not moved forward to regulate it yet. We’re still grinding through that very slow process. So it’s an incredibly complicated and slow process. And as Sharon said, the closer you get to the point of eventually being regulated, the more conflict arises, and the more it slows down.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones to Meigs County, Ohio. Hi, Liz. Welcome to Science Friday.

LIZ: Hi there. Thank you for taking my call.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

LIZ: So I live in Meigs County and was one of the– my family drank this water. I’m so grateful to you for coming in and taking this to the public. And we did do the blood tests, and this was just a horrible experience for us. It was traumatic for us. It still is. We still worry about what our health is going to be like in 10 years, 15 years. And it was just a horrible thing to happen to our community.

And I don’t think we’ve learned anything, because our area is Appalachia Ohio. And we are often, you know, the last ones to be considered when it comes to regulations and things of this nature. And now the fracking injection wells are in my county. And if water, you know– the deep aquifers can be penetrated by– we call it C8, was the word that they used with us. It was called C8. If it can be penetrated by C8, we worry that the fracking injection wells can get into the aquifers.

So it’s just a never-ending fear for us. And we’ve put a home filtration system in for our own water. Even though the company did that, we’ve done our own, because we’re just, you know– people still are afraid of what’s going to happen.

IRA FLATOW: And you ask what you can do. You live in Ohio, and you can vote, right?

LIZ: Oh, I do more than vote. I organize.

[LAUGHS]

You better believe I vote, and I get others to vote.

IRA FLATOW: All right, well, thanks for sharing that. Robert?

ROBERT BILOTT: Yeah, you know, thanks so much for calling. You know, that’s one of the communities that was impacted by the original case. And really, you know, what we’re hoping is, with the book and the movie coming out, that we’re going to be able to finally elevate that story so people know what actually happened in that community and what that community did over the last 20 years to bring this story to light, so that as this chemical was being found and detected and all these additional water supplies all over the world, that people don’t have to do that all over again, that we’re not going to have other communities that have to go through what the caller went through in Meigs County, that we can learn from that and not repeat it.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s talk about learning from that. Let me start with a tweet from Nancy, who wants to know, “Should I just throw away all my old nonstick cookware? Is there a list online of safe brands?” Thank you. I mean, should she just throw away her nonstick cookware and not use them? Robert, what do you think?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, I think one of the primary sources of exposure really has been drinking water. There are potential exposures from a lot of these different products. But the products have been kind of quietly reformulated over the last several years, as Sharon mentioned. You know, as these new chemicals come out onto the market, manufacturers have started reformulating their mix of chemicals that they use in making these.

So I think there’s a concern right now. A lot of those in the scientific community are happy that people have stopped using PFOA in making nonstick pans, for example. But you may see them advertised as PFOA-free, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re PFAS-free. They may have some of these related chemicals that people are really just now learning about. I mean, it took 20 years to learn what we know about PFOA, and we’re just now starting to look into these related PFAS chemicals.

IRA FLATOW: Sharon, did you want to jump in?

SHARON LERNER: Yeah, I guess I’d say that cast iron and oil work really well and did before these nonstick coatings. But I think also you’re getting at this issue which is so many of the uses of these chemicals are not essential. And you find them in all kinds of products, in ski wax, in clothing, in food wrapping, in cosmetics, even. And there’s certainly no need for it.

You know, some people argue that they have some essential uses, some industrial and medical uses. I suppose that’s arguable. But there is no question that you don’t need it on your pan. And I think we need– and you don’t need, you know– we have accepted sort of these modern conveniences of, you know, stain-free carpets. But maybe we just would be OK with a stain on our carpet.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Robert, tell me the status of your lawsuit now, and how many people are involved, and where is it headed?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, that original lawsuit I was mentioning for the community out in West Virginia, Ohio, after the science panel found the links with disease, the 3,500 people who had their cases were able to finally go to court after three trials, where DuPont was found liable, including for punitive damages for causing cancers in that community. Those cases were settled.

And I have since brought a new case I think you referenced earlier, where, now that we’re seeing these related chemicals pop up all over the country, we’re starting to hear that same argument we heard 20 years ago with PFOA. Well, there’s just not enough known about what this does to people.

So I’ve brought a new case in federal court in Ohio seeking to require the companies that put the chemicals out there to actually set up a new scientific panel, independent scientists, to look at all of these chemicals and look at it on a national basis and do whatever science is necessary to tell us exactly what they’ll do in the long term. The companies moved to dismiss that case. The court recently ruled denying those motions. So it’s moving forward.

IRA FLATOW: And what are you seeking, monetary relief, or just stopping making those chemicals?

ROBERT BILOTT: No, what we’re seeking is scientific studies. You know, if the argument is going to be, there simply isn’t any scientific evidence to confirm that these chemicals present risk to humans, if that’s the argument, then the companies that put those out there, we believe ought to be paying to do whatever studies are necessary to resolve that. Exactly what will this stuff do? And that the people drinking it, who are being exposed to it every day as guinea pigs, they shouldn’t be the ones who have to fund and pay for those studies. It should be the people that put it out there and put it into our blood.

IRA FLATOW: Let me just mentioned that we invited DuPont and its spin-off, Chemours, to join us today or provide a statement. DuPont did write us saying, quote, “does not make these chemicals in question.” They don’t make them anymore. And they have, quote, “announced a series of commitments around other limited-use PFASes, which include eliminating use of all PFOA/PFOS-based firefighting foams from our sites and granting royalty-free licenses to those seeking to use PFAS water treatment resin technologies.” We actually have the full DuPont statement up on our website, and Chemours has not yet responded.

We also contacted 3M, which used to manufacture PFOA and supply it to DuPont. And they declined to provide a statement, but pointed us to their website, which we’ll link to along additional information on our website. And just to say, you can find all of that on our sciencefriday.com/pfas site, sciencefriday.com/pfas. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

So Sharon, where does it go from here? Someone who’s covered this for four years now?

SHARON LERNER: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: What are your feelings about this?

[SHARON LAUGHS]

Are you still feeling helpless?

SHARON LERNER: I guess, I mean, I started with a three-part series that I thought it would end there, and then it was at 11, and I’ve written more than 40 articles on this. And I think I’ve accepted that this issue is not going away, and the chemicals are not going away. Unfortunately, they literally won’t go away. They don’t break down. They don’t break down.

IRA FLATOW: They don’t.

SHARON LERNER: So they’re going to be on the planet long after humans are. And as we’ve said, it’s not– you know, when it started, I thought of this as an Ohio, West Virginia issue. It’s the whole nation. It’s the whole world. And as you mentioned, it’s not just blood. It’s in breast milk. It’s in placental tissue. It’s in babies when they’re born. It’s their first meal, you know? So it’s something we’re going to have to understand and how it affects us. And so unfortunately, this issue will– I will continue to write about it, maybe not forever, but it will go on for quite a long time.

IRA FLATOW: Robert, is this an endocrine disruptor class of chemicals?

ROBERT BILOTT: Well, I think that’s among the areas that are being researched right now, is to try to find out exactly what all effects these chemicals have. Unfortunately, they’re being found to have a wide variety of effects, including decreasing immune function, decreasing the effectiveness of vaccines.

And, you know, as Sharon mentioned, the real concern is this stuff doesn’t break down. And so it’s great that companies have phased out making some of these– the long-chain C8s, for example. But that doesn’t address all of the years and thousands of tons of this stuff that’s already out in our environment, in the soil, in the water, in our blood. And that’s what I think we have to deal with now, is, what do we do about what’s already out there?

IRA FLATOW: And the first thing that you’re asking for is to actually study the chemicals, study the problem itself?

ROBERT BILOTT: Right. I think that we already have more than enough information on at least PFOA, that there’s more than enough on that chemical to move forward and take effective steps to regulate that. There’s no reason that we aren’t doing that already. But if others are going to claim that some of these other related chemicals, that there isn’t quite as much information, then yeah, we need to have that information and have those studies done. And the people who are exposed to it shouldn’t be the ones paying to do it, though.

SHARON LERNER: And I would just add, until we have that information, we should not be allowing new chemicals in this class onto the market, which the EPA is currently doing.

IRA FLATOW: Right, well, we’re going to follow this story. And I want to thank both of you for sharing it with us. Sharon Lerner, reporter at The Intercept covering health and the environment. And Robert Bilott, you have a new book out. It’s called Exposure. And also, a movie, a film called Dark Waters, is coming out in theaters November 22, which is based on your life story, about that’s taken you now 20 years to go after this. We wish you good luck with both things, Robert, and Sharon, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

SHARON LERNER: Thank you for having me.

ROBERT BILOTT: Thanks much for having me.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Elah Feder is the former senior producer for podcasts at Science Friday. She produced the Science Diction podcast, and co-hosted and produced the Undiscovered podcast.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.