What Will The Pandemic Look Like During The Winter?

17:35 minutes

This story is part of Science Friday’s coverage on the novel coronavirus, the agent of the disease COVID-19. Listen to experts discuss the spread, outbreak response, and treatment.

It’s been almost a year since officials in China announced the spread of a mysterious pneumonia, and identified the first COVID-19 patients. On January 21, the first U.S. COVID-19 case was confirmed in Washington State. And new record highs for cases were set this week.

Since March, just about every country in the world has tried to get a handle on the pandemic using different interventions. Infectious disease expert Michael Osterholm and physician Abraar Karan discuss what pandemic planning might look like heading into the winter and during the second year of the virus.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Michael Osterholm is Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Abraar Karan is a physician at Harvard Medical School and Brigham And Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. New record highs for COVID-19 cases were set this week. It’s been almost a year since officials in China announced last December the spread of a mysterious pneumonia, identifying the first COVID-19 patients.

On January 21st, the first US COVID-19 case was confirmed in Washington state. Since that time, just about every country in the world has tried to get a handle on the pandemic in some way of their own. We’ve been through lockdown, social distancing, masks and no masks, vaccine trials, hydroxychloroquine, and bleach.

What have we learned so far as we head into the winter? What might the pandemic plan in the US look like? That’s what we’re going to talk about. With me are my guests, Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, and Dr. Abraar Karan, physician at Harvard Med School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. Welcome back, gentlemen.

ABRAAR KARAN: Thanks for having us.

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: Thank you.

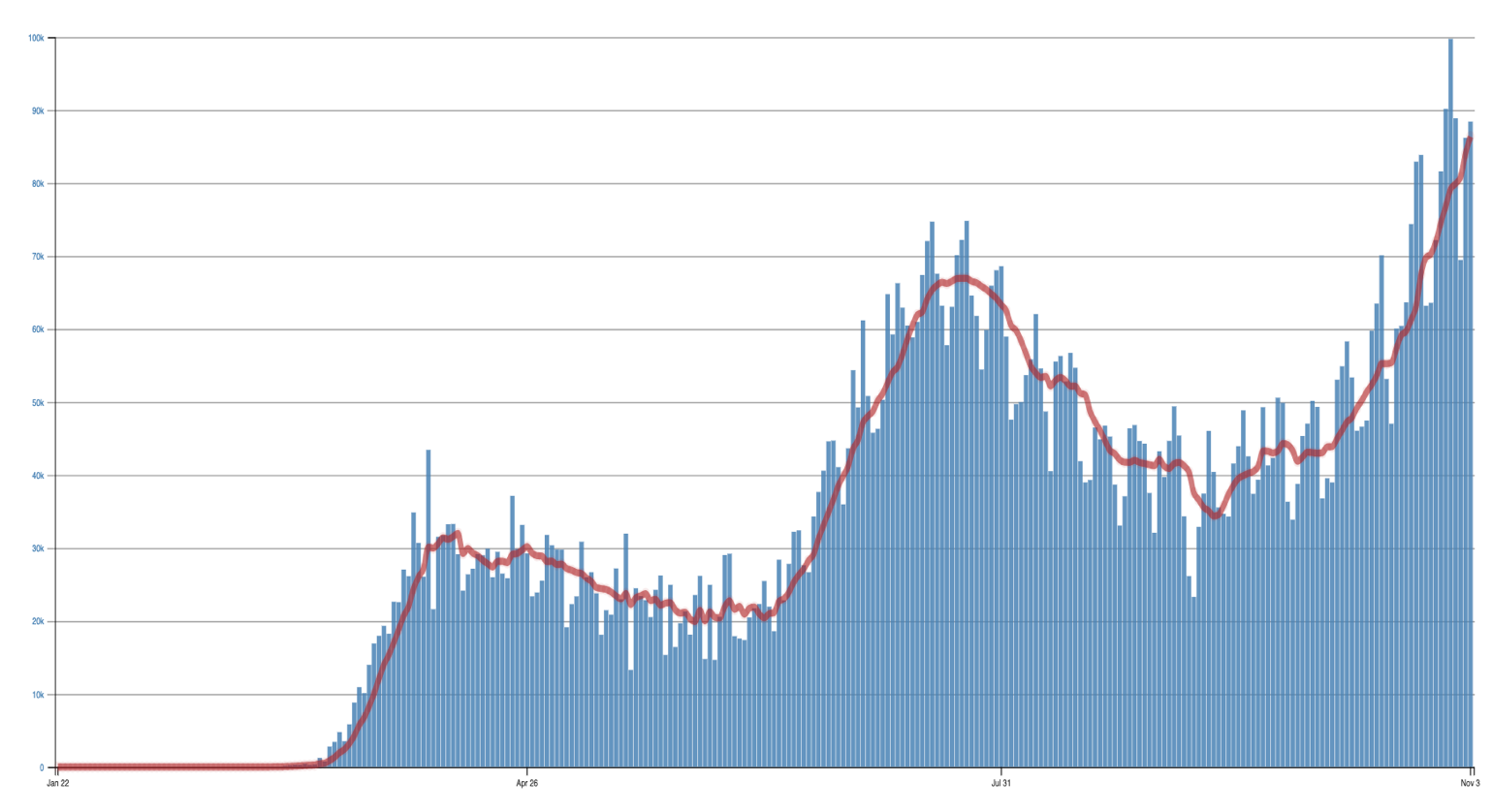

IRA FLATOW: Michael, let me begin with you. We had you on this show way back last January. We’re almost reaching a year, as I say, of the pandemic. There are eight million COVID cases in the US, spikes in the Midwest and in the Plains. Are we in a second wave, or are we still in a first wave? It doesn’t look like we actually ever flattened that curve.

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: When you look back at where we were, we could have and should have known, actually, in January, that we were going to experience a global pandemic. And as we discussed, this is what unfolded.

But back then, we didn’t understand would this be like an influenza pandemic that would truly have waves, where, in fact, if you look at the 10 influenza pandemics of the last 250 years, there was always a first wave that would– you see a peak of cases, and it would drop on its own after two or three months with no human intervention, be absent, or at least relatively absent, for a number of additional months, and then we’d see a big second wave.

And we weren’t sure if a coronavirus would do something like that. But in fact, over time, we’ve come to realize, no, it’s more like a coronavirus forest fire, where, basically, it’ll burn where there’s human wood. And we may do activities to suppress that transmission, which was like firefighters holding it down. And when it does burn, it won’t always burn evenly. It will burn some areas much heavier than others.

And so what you’re seeing in the world today is why we don’t see waves as such. As we are doing in Asia right now, we don’t see waves. They’ve really controlled it quite well. In our country, what we’ve done is we saw that April peak, and we took efforts to suppress cases by distancing and so forth. But then a July peak occurred. And we did it again. But now here we are, back at this new peak activity, which is only going to get much higher.

And each one of those are related to just how serious we took the virus. Europe’s the same way. They did a lot to really knock down transmission in April and May, and we did. But they continued to keep that minimization of human contact, reducing transmission until August, and they let the foot off the brake quite quickly. And now we’re seeing what’s happening there. So I really think this is more of just a forest fires like model, not a wave model.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask you, Dr. Karan. It’s been a year since we’ve talked about the beginnings of coronavirus. What do you think we have learned in that year since then?

ABRAAR KARAN: I think there’s a lot that we’ve learned, particularly around sort of the way in which the virus is spreading, how it’s spreading most efficiently, and sort of a little bit in terms of the dynamics of how it’s spreading, particularly around clusters of people, and that not everybody is transmitting the virus as efficiently or to the same number of people. And I think that that’s something that we can use to our advantage. If we’re able to sort of stop that cluster spreading, then we can actually get a better control of sort of the rate of increase.

IRA FLATOW: As we head into the winter with colder weather and another year of the pandemic, what concerns you? What are you thinking most about, Michael?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: I think, first of all, we have this combination right now of a perfect storm. We have pandemic fatigue, which is people who really do believe that the pandemic is real. But it’s just been six, eight months. I’ve got to go back to it.

So we’re seeing, whether it be in colleges and universities, weddings, funerals, going back to the gym, eating in bars and restaurants, having large get-togethers, sporting events– I mean, I’ve got a situation right here in Minnesota next week. 720,000 Minnesotans are going to go deer hunting, of which many of them are going to be spending long times in deer cabins with five, six, seven other people. We’re going to see lots of transmission there. So I think that we have that pandemic fatigue issue.

Then we have pandemic anger, which is this one where, basically, people don’t believe this is real. And so I don’t care what you tell them or how you tell them. They’re going to just basically deny it and not take any public health measures as recommended. And then you put that together with indoor air. As you just said, it’s the most potent mix I could imagine. Because indoor air will clearly dramatically enhance this transmission.

And so this is why I think this period right now, between now and getting a vaccine first, second quarter of next year, and then most of the population having access, hopefully, by the third quarter, it’s going to be the darkest weeks of this pandemic, I believe.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Karan, you’re a physician. You’ve been working in a hospital throughout the pandemic. What are your concerns about being prepared or having enough facilities, PPE, all of those things? Do you think it’s there for you?

ABRAAR KARAN: Yeah, I think it’s– at least now, it is, in the sense that we’ve been through this once in Boston. So we had to have N95s that were recycled weekly. We had to use N95s very carefully, right? I had my N95, my PPE. I knew where it was. I would not lose it. And there was a time in the very beginning where we didn’t even have that.

But I think that one issue is that even though people say, oh, maybe you don’t die from this, well, you very well may need to be hospitalized and use up a hospital bed, meaning that other people that need to be hospitalized for other things no longer may have that bed. So you may need to get remdesivir. You may need to get dexamethasone. You may need to have your oxygen monitored, et cetera, and be in the hospital.

And so, this sort of over focus on mortality is so problematic because hospital beds are very limited. And as Dr. Osterholm was saying, our energy as staff is limited, too, right? I’m young. I’m early in my career. I have energy still. I mean, it’s not going to be unlimited, though.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Osterholm, we know that Black and certain communities were hit harder by the pandemic. Now as we anticipate the winter cases coming up, what needs to be put in place to help these communities?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: Well, this is a really important point and one that, as a nation, we’ve really not addressed head on. I mean, if you look, for example, among essential workers, people who are keeping our everyday economy going, much, much of the workforce is an overrepresentation of those from the Black and indigenous population, community of colors.

That whole area involves much more than just their exposure at work, but living at home. I mean, when I hear, for example, people say, well, we’ll just bubble up those at risk– you’re a single mom. You have two young kids, and your mom lives with you in an apartment with two bedrooms. Tell me how you bubble that up when she comes home with the virus.

And so we’ve seen this kind of socioeconomic status combination with occupational risk be a challenge. And I don’t have an easy answer, other than to say that we have to recognize that just merely letting this virus go willy nilly in our communities is absolutely immoral.

If I can just also add one other piece, I appreciate your answer just now because I think healthcare workers are also going to start experience another kind of pandemic fatigue. That of not that they don’t care, not that they don’t want to deal with it, but they’re burning out. We have to understand that the country’s resources are not going to be limited to number of beds. It’s going to be limited by number of staff.

And I have seen far too many people on the front lines who, after even weeks or a few months, are beginning to burn out in such a way. I mean, people who just will repeat over again, I am broken. I am just broken. We have to understand what’s happening to our healthcare workers in this country and support them from a mental health standpoint in ways we haven’t done. Because if they’re not on the frontlines, we really are in trouble.

IRA FLATOW: In the beginning of the pandemic, we all remember Italy and other countries had tight lockdowns. Now the UK is facing another lockdown. Do lockdowns work? Do we need to think about lockdowns in perhaps a different way, Dr. Karan?

ABRAAR KARAN: I personally would say that I don’t think lockdowns are a strategy so much as they’re an emergency backstop. They’re a way to quickly stop transmission. And what that does is it essentially is buying you time to set up a public health system that can trace the virus, that can test people efficiently, that can set up healthcare resources. It’s essentially stopping everything so that you can get things restarted again and approach it in the right way.

The second part is to not overwhelm your healthcare system, and those are both related. But with the past lockdowns that we had, our federal sort of response did not use that time as well as it could have to set up the systems that we need. And I think that’s the problem. And so when it becomes politicized and people say, oh, well, it’s either lockdowns or it’s sort of this other– and herd immunity, et cetera. I’m saying, well, no, there was a point to locking down, and that wasn’t done, so let’s focus on getting that done.

IRA FLATOW: Michael, would you agree?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: Oh, I agree completely. And in fact, I may even take it one step further and say, the Asian countries have taught us what can be done to control this virus. And watch what happens to their economy when it comes back when they actually do control the virus. So if you want to see minimizing pain and suffering, both physically and economically, look at them.

But in addition, in a column, an op-ed piece that Neel Kashkari, the president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, and I did in The New York Times back in August, we actually laid out how lockdowns could actually be effective and support everyone. Right now, we’ve watched an amazing thing happen during this pandemic. We’ve gone from about 8% of our income to savings up to over 22%. That money is sitting there in banks, waiting for somebody to borrow it. Lowest interest rates in modern history.

Our government could borrow that money as an investment back to cover the cost of people who have lost their work, of businesses who have been hurt, of city, state, county governments that have suffered, and actually invest back in them to do exactly what Dr. Karan just said, and to basically support this concept of a lockdown in a way that says, we do minimize economic pain and suffering that’s occurred.

If we did that and then did exactly as he just said, where then we get testing and follow contact tracing, isolation, and quarantine together, which means we need a national plan for testing, which means we need to have the resources there to support that, we could have a much different picture between now and the time of a vaccine. We just haven’t done it.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking about a vaccine, there has been talk since the beginning of the pandemic of a vaccine is coming, it’s not coming. Michael, when do you predict we will start seeing a vaccine and I guess, just as importantly, the distribution on a larger scale?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: Well, first of all, we will see vaccines, I believe, in the first quarter of this next year. I think that they’ll be there. How much will be there will be a challenge. I think there are two things about the vaccines that we still have to understand. One is just how well they protect. And I think at this point, we don’t know yet with serious disease exactly what that’s going to look like. 50%, 60%, 70%– we don’t know.

The second thing is, will people take them? We’re seeing well over half the US population is highly skeptical of even taking this vaccine. And particularly, in some of the communities you just mentioned, in the Black, indigenous, and communities of colors populations, there’s a very high level of skepticism about this. Yet, that’s where we need to get it.

So it’s one thing to have a vaccine. It’s another to have a vaccination that’s actually in your arm. And so one of the challenges we’re going to have is both getting the vaccine out there when it does become available and getting people to actually use it. And I think that’s a huge challenge we’re not really addressing yet in a very meaningful way.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Speaking of a challenge, this pandemic, as we all have seen during this campaign, has been politicized. Now that the election is over, do you think we’ll see a difference in how officials approach the pandemic planning?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: At this point, we don’t really know. I think there surely is every reason to think that this could be the darkest times in terms of convincing people that this is a, one, a real public health emergency. Number two, that there are things we can do about it. We just have to work together.

And three, what we need right now more than anything in the world, I think, is not just more science. We need an FDR like moment. We need someone that can tell a story about where we’re at, where we’re going, why we’re going there, how we’re going to get there, how we’ll make things different and believe in it. And I think that by itself could be a dramatic improvement on what’s happening right now. That is my hope. We need a story. And we need it very, very quickly.

IRA FLATOW: Do you foresee such a story happening?

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: At this point, I have every reason to believe it can. I think when you’re dying and when it’s your family members who are dying, it has a way of cutting through the truth. And the problem we have is, I don’t want to have people become believers in this pandemic because of the loss of a loved one. I’ve seen too many people already who denied that this pandemic existed only to have the reality of it hit them home at home when they lose a loved one.

And so our job, if we can do it most effectively, is to get people to understand this in advance of that. And that’s the challenge we have right now. If we could just tell all the stories that our frontline healthcare workers could tell right now about the pain, the suffering, the agony, the desperation, the loneliness, watching someone die alone, then people, I think, would get a better sense. My god, this is real, and this is bad.

ABRAAR KARAN: To sort of add to Dr. Osterholm’s point there, Ira, I have countless stories. I remember one on Mother’s Day this year. I was in full gown PPE with a woman who had COVID, was dying, was sort of end of life at that point. And I was holding an iPad so that she could FaceTime with her daughter. And these are the kind of things that people went through– real, real, real tragedies.

And then, on the other hand, this week alone, I’ve been seeing people, young, healthy people who had COVID, didn’t have terrible disease initially, and are coming in with really debilitating symptoms, symptoms that you don’t see in young, healthy people. And we don’t have a good explanation for them, right? And so we’re doing more workup. We’re understanding more.

But when you then argue for something like herd immunity, let it sort of infect young people, we’re talking about not just mortality, there is serious morbidity that we don’t fully understand. I mean, it’s really careless to let people get infected with this.

IRA FLATOW: I don’t know how to answer these because if you watch enough, I guess, television, you’ve seen so many of these stories that you’re talking about on the challenges to the healthcare workers, of the people dying on ventilators, the tragedy in families. And you don’t get the impression that for a large part of the country, it has moved the needle one bit.

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: One of the things I think we have to remember– and this is actually the implication for our future– is that if you look across the board, clearly, there are population areas where it’s higher. But we’re still looking at about 12% to 14% of the US population has been infected with this virus. That’s roughly one out of 10. So there are still a lot of people out there. While they may know somebody, it’s not really hit them at home yet.

That is going to change. This virus is not going to rest because we’re done with it. Pretty soon, more and more of these people who say, well, I knew somebody, but I don’t think they really died from COVID, and then it actually be one of your loved ones.

And I think that one of the things Dr. Karan really hit home on just now, please know, everyone, the worst thing you can imagine is when one of your loved one is dying, and you can’t be there. That is a triple tragedy on top of a tragedy on top of a tragedy. And that’s what we’re trying to avoid. And that’s going to happen more and more often. So our job is to try to help people get there before they have to go through it so that they make the changes that can help reduce transmission.

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good place to stop. And on a hopeful note, I want to thank both of you for taking time to be with us today. Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Dr. Abraar Karan, physician at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, thank you both, again, for taking the time, and have a safe winter.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.