Painting The Brain As A Sacred Object

6:19 minutes

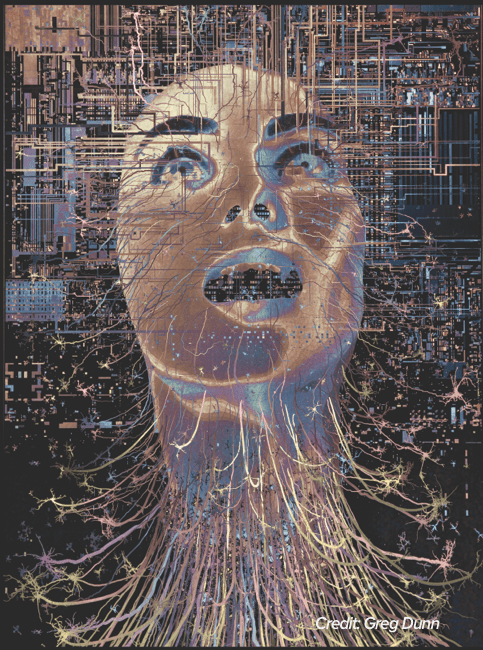

Back in 2011, after Greg Dunn completed his PhD in neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania, he didn’t return to the lab. Instead, he decided to focus on art specifically, merging his interests in Japanese sumi-e ink painting with his knowledge of the human brain. “The only difference between a landscape of a forest and a landscape of a brain is you need a microscope to see one and not the other,” Dunn told Science Friday.

Now his work has developed further. Using the techniques of microetching and lithographing, Dunn has created a project called “Self Reflected,” which visualizes what it might look like to see all the neurons of the brain connected and firing. He joins Ira to discuss his work, which is also the subject of our latest SciArts video.

Greg Dunn is an artist and neuroscientist based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

IRA FLATOW: What would happen if your brain could see itself? Well, outside of an MRI machine, the closest thing we’re going to get to that is likely the work of my next guest, neuroscientist and artist Greg Dunn. His new project, titled Self Reflected, shows us what it might look like to see all the neurons of the brain connected and firing. He uses the technique of microetching, and it’s a subject of our latest sci arts video. Greg Dunn, welcome to Science Friday.

GREG DUNN: Howdy, Ira. Good to chat with you.

IRA FLATOW: You got your PhD in neuroscience. And then what? You became an artist who creates pictures of the brain? Why do you do this kind of work?

GREG DUNN: Well, good question– I mean, this is not my intended career path from when I was five years old. It just kind of happened this way. And I found that combining my artistic skills with my kind of scientific interest was a good way to keep myself interested and satisfied. But also to, I think, communicate to the general public in a way that I wasn’t able to just being in the lab.

IRA FLATOW: This is gorgeous stuff. I was looking at the video up on our website. And it’s up there– ScienceFriday.com/brainart. Explain what microetching is to our listeners.

GREG DUNN: Microetching is essentially– imagine you have a mirror finished piece of metal. Or we actually use gold, in our case. And just like you’re keying a car, you put a big scratch in it. That scratch is going to reflect light in a very specific way, depending upon where it’s illuminated from. And you can see it very clearly in this mirrored background.

Now imagine that you’re essentially drawing the outlines of various objects in specific angles of etch. What ends up happening is that when you have a light source over this piece, depending upon the angle of etch at any given spot on the microetching, the viewer will be able to see elements of the piece appear and disappear. And by using a lot of physics and math, you can actually cause this microetching to animate neural forms, in this case. I mean, it’s a flexible technique that can be used for a lot of different things. But in our case, we use it to depict action potentials in the communication of neurons in the brain.

IRA FLATOW: Depending on what angle you’re looking at it, you’ll see something else. It’s, like, three dimensional.

GREG DUNN: That’s right. Yeah. It’s a distant cousin of holography. It’s closer to lenticular printing, I would say.

But there is more of a kind of deliberate engineering of the surface in order to make those animations happen. Oftentimes similar techniques will have an object flash on and off. In our case, we’re able to make continuous animations by varying these angles continuously.

IRA FLATOW: Talking with Greg Dunn, neuroscientist and artist based in Philadelphia, on Science Friday from WNYC Studios. It’s gorgeous. The video, the stuff is gorgeous. Have you ever thought about– the first thing I thought about is making virtual reality part of this. You know, so you could touch it with a virtual reality goggles on.

GREG DUNN: Yeah. That’s a good question. It’s something that I have considered. I mean, just my personal kind of proclivities are such that I prefer to make physical objects at the end of the day, as opposed to be working purely digital. Although for sure, you know, the potential of 3D, a purely 3D medium, is very high. Yeah. So I’ve strayed away from it up to this point, although perhaps–

IRA FLATOW: I’m not– no, I mean, don’t get me wrong. I’m not encouraging you to do this. Because I love the physicality of it and the fact that you don’t have to make it– the object sort of speaks for itself in the way that you etch these photos. It’s just–

GREG DUNN: Yeah, well–

IRA FLATOW: –gorgeous.

GREG DUNN: –that’s actually– yeah thank you– and it’s actually a very deliberate part of the process. That when somebody sees a microetching that’s hanging in a museum, or in somebody’s house, for example, it’s probably the first time they’ve ever seen any art like it. So I mean, we’ve essentially invented this technique.

And I should say I work with my collaborator, Dr. Bryan Edwards, who’s an applied physicist, on this work. And the idea that you have a physical object which is something you haven’t seen before is designed to help emotionally draw in the viewer. A lot of people have looked at a TV monitor and seen, you know, brain activity simulated in that way.

But to have that extra added element of surprise to it, I think that it helps to engage people’s emotions. And that’s truly how people learn. I mean, once you’ve engaged a person’s emotional kind of structure in their brain and you’ve given them that wow moment, that moment where they’re not quite sure how this works, it encourages them to ask deeper questions about what the artwork is.

IRA FLATOW: And where can your artwork be seen?

GREG DUNN: Well, the full size Self Reflected can be seen at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. There are smaller versions of it at several museums around the country. And I have art hanging in people’s homes, in neuroscience institutes, that sort of thing, you know, from sea to shining sea.

IRA FLATOW: And so the artwork shows us long strings of neurons, stretched out across– beautiful depictions. Have you thought of any other cell structures you might go into?

GREG DUNN: Yeah. Some of my earlier work, which is more based on the tenants of Asian Art, explores different cell types, different types of interneurons. You know, the piece Self Reflected contains, maybe, 150 different cell types in it, as well. And I see my future work straying away from just a purely anatomical and going more into the kind of human element of the brain. You know, what is our subjective experience like?

Because up to this point, I’ve depicted the brain artistically in more of its typical functioning state. But there are a lot of ways in which the brain can go wrong. You know, a lot of people suffer very profoundly from neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. And so the next two years of my career or so are going to be dedicated to towards those types of depictions.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we’ll have to hook you up with our friend, Dr. Eric Kandel, who can probably add some stuff.

GREG DUNN: Oh, yeah. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. He’s into art, also.

GREG DUNN: [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you.

GREG DUNN: Indeed.

IRA FLATOW: And this is– you know, we’ve been talking about it. But you really can’t appreciate it until you take a look at it. So go check out our video about Greg’s latest artwork. It’s up on our website at ScienceFriday.com/brainart. Greg Dunn, congratulations, and thank you for sharing this with us.

GREG DUNN: Yeah. Absolutely. Thanks for your time, Ira. I appreciate it.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.