Oliver Sacks, In His Own Words

16:16 minutes

The neurologist Oliver Sacks died just over five years ago after a sudden diagnosis of metastatic cancer. Over his long career, Sacks explored mysteries of both human mental abnormalities and the natural world. Endlessly empathetic and curious, Sacks shared his clinical observations through a series of books and articles, and appeared on Science Friday many times to discuss his work.

A new film released this week describes Sacks’ life through his own words and reflections from those close to him—including the story behind the book ‘Awakenings,’ which later became a major motion picture and propelled Sacks into worldwide prominence. It also details his difficult childhood, his addiction to amphetamines in young adulthood, and his homosexuality, including three decades of celibacy before he found love in the last four years of his life.

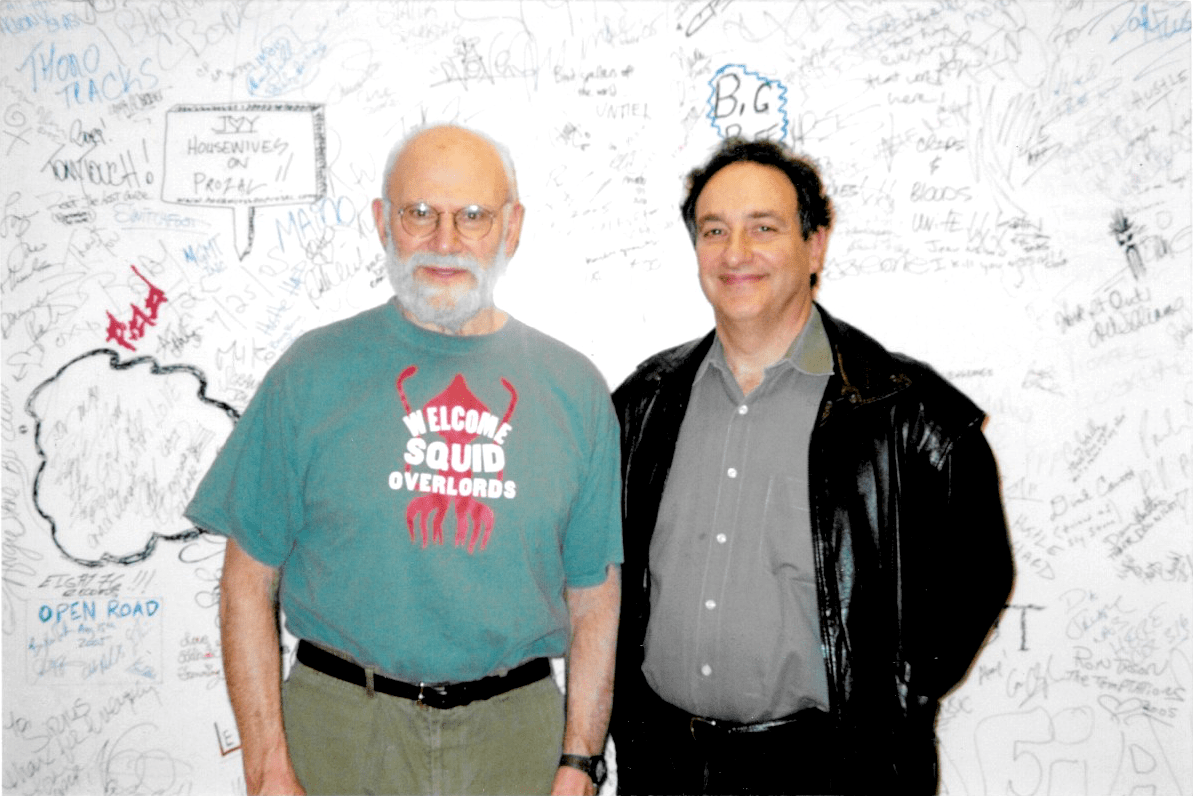

Ric Burns, director of the film Oliver Sacks: His Own Life, joins Ira to talk about the life and legacy of Oliver Sacks. The film premieres nationwide this week on the Kino Marquee and Film Forum virtual platforms.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Ric Burns is the director of Oliver Sacks: His Own Life. He’s at Steeplechase Films in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Just over five years ago last month, neurologist Oliver Sacks passed away. He was a man curious about everything.

And while his work focused on the inner world of the brain and its many fascinating variations and disorders, he also found inspiration and wonder in things from ferns to cycads, cephalopods to minerals. And he shared that curiosity with the world through his many eloquent books. He spoke with us on Science Friday many times, you may recall. Way back in 1995, he talked to a caller about the goals of his writing.

OLIVER SACKS: I don’t quite know what I want to achieve. Although in the first place, I want to redirect attention. I want to arouse excitement and curiosity and, again, make people feel, including some of my colleagues, that even on the back wards and in particular individuals, there is a huge amount to be learnt, that one doesn’t have to have vast series. I think that I want to direct attention, again, to what it means to be an individual responding in a particular way to a challenge.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Oliver Sacks talking about his work 25 years ago. And now there is a new documentary that looks at the life and legacy of Oliver Sacks, with his own words and comments from people who knew him best. Joining me now is director Ric Burns. His film, Oliver Sacks, His Own Life, premiered nationwide this week on the virtual cinema platform, Kino Marquee and Film Forum Virtual Cinema. Welcome to Science Friday.

RIC BURNS: Thank you, Ira. It’s so great to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. You filmed this with his own participation. How did that happen? Give me the genesis of this film.

RIC BURNS: For me, it was kind of mindboggling. 5 and 1/2 years ago, in early January 2015, we got a call from Kate Edgar. Kate Edgar, you know, is Oliver’s incredible editor, chief of staff. Somebody once said Kate is his everything.

And I didn’t know Kate and I didn’t know Oliver except, of course, I knew his writing. And she called up through a friend of a friend and said, Oliver is going to die. Will you come in and start filming?

And so we did, without any sort of preparation or kind of fundraising. And it’s important to remember that, in 2015, what wasn’t known about Oliver Sacks, who was so celebrated and so widely known was that he was homosexual, that he had had an extremely difficult, I would say even tormented life. His childhood, which was blessed in many respects, was also extremely painful.

And all of that, his sexuality, his difficulty with that, his relationship to his family, particularly his mother and perhaps his older brother, Michael, who was one of four, who was psychotic, who was schizophrenic, his flight, really, to America when he was 30 to get away from all that, and of course, you can’t really ever get away from all that. He went to San Francisco, kept working as a neurologist, starting up there. Got involved with amphetamines, was woefully addicted, and really kind of had, you know, maybe two if not more wheels off the ground for much of his early adult life.

Really unhappy, never really found his way in a relationship. All of that was really below the surface of this vastly calmer, even soothing persona which came off the surface of his writing. And which, in some sense, the point of his writing was to allow him a place to be where he didn’t have to contend with those things. And he certainly didn’t want to interact with other people on that basis.

So you know, we suddenly walked into that. And we’re thrown into the deep end of Oliver Sacks. At the very moment, 81 years old, he had written but not yet published this remarkably candid memoir, talking about all those things which he’d never really discussed before outside a small circle of people, On The Move.

It hadn’t been published yet. And then he got this mortal diagnosis, a metastasized cancer. So he was a man who wanted to sum up. And he wanted to do so, as Kate pointed out, not only in words but also on film.

IRA FLATOW: And you spoke with many, many people who were very close to Oliver Sacks. And they all offered sort of a vision of who they thought he was.

RIC BURNS: Yeah. Absolutely. It’s interesting. You know, we spoke with Oliver for about 90 hours in February and April and June of 2015. And then he died on August 30, 2015.

And we spoke with 25 people who’d known him well, from patients like Shane Fistell and writers like Lawrence Weschler and Robert Krulwich, who had gone up to try to find out who this guy was early on, as had Ren Weschler. Everybody had their own Oliver. But there is a remarkable consistency in their viewpoints.

And the film is really, you know, in his own words and in the words of those 25 people who knew him best, including family members, Kate. The only person he ever had a really satisfying and deep romantic and sexual relationship, a remarkable person, Bill Hayes, photographer and writer, who really kind of, like, in the December of Oliver’s life, they met. And Oliver had been, at that point, celibate for 35 years. That was not something he was expecting.

And so there is a kind of a narrative, extraordinary narrative shape to his life that’s very moving. And that this amazing assortment of neurologists and neuroscientists and patients and friends and partners spoke to. And which then, by about 2016, we had to sit down and say, so what’s this story all about?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. You mentioned Robert Krulwich, who’s an old, longtime friend of mine also and the host of Radiolab. And he really found a very fine way of summing up finally finding the love of his life. And we have a clip from that in the film.

[VIDEO PLAYBACK]

– And the last four years, I think, felt like an enormous sigh in so many directions, to his friends, to his best friends, to pretty much everybody. He’d found balance.

IRA FLATOW: He’d found balance.

OLIVER SACKS: Well it’s really, really true, I think. I mean, I came to understand that that was true. Obviously, we knew him only in the way filmmakers would know someone, briefly, intensely, and there at the very end.

And Robert Krulwich also said, I know you’ll remember, Ira, this remarkable thing. That his patients were these people who were very, very in trouble, lonely, as Robert put it, left out, often seen as woefully other, afflicted with some kind of neuroatypicality. And he storied them back into the world.

And Ren Weschler, who introduced Robert to Oliver, said something very similar, saying, you know, he used narrative as therapy. And that was really kind of the genius of Oliver. And I think there was an aspect of genius in that.

That at a time when neuroscience and neurology was extremely quantitative and extremely based on objective criteria, Oliver was doing something– you mentioned it so powerfully and beautifully earlier, in the first clip from Oliver– he’s interested in observing individuals and their experience. He’s interested in their unique consciousness. And that subjectivity was his subject, partly because his own subjectivity was, his own self, was very complicated and mysterious and troubling even to Oliver.

IRA FLATOW: That, I think, comes out throughout the film in how personal his medicine was. I want to play a Science Friday clip we had from 2012 in which he talked about his style of medicine.

OLIVER SACKS: A lot of medicine now consists of large statistical studies. And these may be extremely important. For example, one could never have shown that tobacco is related to bronchial cancer without a huge statistical starter. But for myself, the individual person and their story is always central. And I care for them. And I don’t think medicine or medical care is possible without a deep caring.

IRA FLATOW: You talk about this in the film. I thought this was very, very interesting. He was criticized by other scientists for not having a theory about many of the illnesses he observed and wrote about. And you show in the movie that he pushed back by saying, hey, look, I’m just an observer who gives you theorists something to think about. And you also back that up with something Temple Grandin describes him in the film.

TEMPLE GRANDIN: What Oliver did is sort of like the Hubble Space Telescope of neurology. It’s astronomy of the mind.

IRA FLATOW: What a great quote.

RIC BURNS: What a great quote. I mean, it’s so true. I mean, this sense that the subjective inward experience, which is obviously what we all– it’s the most familiar and the most mysterious part of all of our lives. But that is a material kind of data and that he wanted to investigate that and not see it as something which is outside the purview of science. And that just because you couldn’t measure it and, indeed, couldn’t see it, doesn’t mean it wasn’t there and didn’t mean it was the whole reason why we were doing any of this stuff.

And so that– he made subjectivity available to scientific inquiry. And of course, it’s not going to be mainly done through true objective means of science. MRIs can see your brain sparking away and CAT scans. But you know, how does it feel, Ira, to be listening right now? How does it feel to be a Touretter or to wake up hung over in the morning or to whatever? That is the experience Oliver was trying to plumb and which was really considered not unimportant by neurologists of Oliver’s time in the ’60s and ’70s and ’80s, but kind of unavailable to the instruments of science.

And he said, well, what about empathy? What about imagination? What about spending a long time with these people? What about constructing a story in tandem with them, which then becomes a token of exchange between them and you, and hence, as Robert Krulwich put it, allows you to help story them back into the world and give them a form of therapy?

IRA FLATOW: I attended a party for his last book, On The Move, his second autobiography, published a few months before his death. And speaking with him, I found there really was no melancholy in him at the party. And I jokingly said to him, so what comes next?

And he very seriously said, there will be another book after I’m gone. And you see that all the people that are in your room will have tears going on. And he’s saying, I see you’re all crying. But I’m not. It hasn’t sunk in yet, perhaps.

RIC BURNS: Right. And I think, in a funny way, the moment you’re describing in the film, he had just finished reading the as yet unpublished op ed piece that came out in The New York Times in February announcing his mortal illness. And when it’s over, he looked up and there was all of us, obviously old friends, and Kate Edgar, and his boyfriend, Billy Hayes, but you know, Buddy Squires, our cinematographer, and our sound person, and me. And he says, you know, he looked at us kind of sheepishly, just sort of suddenly taking it in.

And he said this amazing thing. He said, well, there it is. Which had huge kind of resonance at that moment, and then said, you know, I do see tears all around me. But I have yet to shed them myself.

And I think that he was committed– he said he had anxiety. He had uncertainty. And he knew there was sorrow at his impending demise. But I think that he so clearly knew this is it. We all live 100% within the envelope of the material world that made us possible.

And he wanted to explore that. And so the gift that he gave all of us, I mean, as Ren Weschler put it, he gave a masterclass in how to die, which sounds so gloomy. But Ira, it turns out, to be as moving and as inspiring as almost anything will ever have the good fortune of coming in contact with.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. And this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

When I see a biography of a person released after their deaths, like this wonderful film you made, it makes me sad sometimes. Because I wonder if that film had been done and released while they were still alive, I might have been able to enjoy that person a little bit more for their accomplishments while they were alive. Do you ever feel that way and say, I wish I had been here a year ago, or five years ago, or 10 years ago, and done this film?

RIC BURNS: You know, with respect, 100% not. You know, there we were, early January, in the last year, six months of Oliver’s life. The film is about his entire life. But about especially his relationship to those last six months. And that is the film.

And we wouldn’t even be there if he hadn’t got that mortal diagnosis. And Kate Edgar call us up. And so the very point of departure, the door we walked through was the door of Oliver Sacks, who was going to die.

And that conditioned every aspect of the film. And therefore, I don’t regret that Oliver never saw it. I don’t regret that it wasn’t available for people to understand who he was better while he was alive. But rather, to hear this voice.

You know, it’s funny you always sounded the same. You’ve played clips from ’95 and from 2012. And it could have been yesterday.

And not just because of the quality of your incredible recording, but because Oliver was as, Roberto Calasso, his Italian editor put it, he was the most childlike person from beginning to end. And so there was this remarkable through line in Oliver, which is a man-child-man, constantly looking around with a sense of wonder and curiosity and excitement, including, finally, wonder and curiosity about his own end and how would that transpire. And that is an aspect of courage and a model which is huge for anybody, I think.

IRA FLATOW: Hard to believe it’s been five years. Ric Burns, we’ve run out of time. I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today.

RIC BURNS: Thank you, Ira, for having me. It really means a lot to me.

IRA FLATOW: Ric Burns, director of Oliver Sacks, His Own Life, a terrific, terrific film. It premiered nationwide this week on the virtual cinema platform Kino Marquee and Film Form Virtual Cinema. Thanks for being with us today.

If you’d like to see a video tour given by Oliver Sacks, a tour of his own office with all of those tchotchkes and all of those elements, we have it up on our website. It’s part of our collections up there. You can go to our website, ScienceFriday.com/OliverSacks, part of our Desktop Diary series.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.