What’s Behind The Blockchain-Based Art Boom?

17:14 minutes

From multi-million dollar art sales to short NBA video clips, non-fungible tokens have taken off as a way to license media in the digital realm. The blockchain-based tokens, which function as a certificate of ownership for purchasers, produce a dramatic amount of carbon emissions and aren’t actually new—but in the first quarter of 2021, buyers spent $2 billion dollars purchasing NFTs on online marketplaces. Writers, musicians, and artists are all now experimenting with them, and big brands are also jumping on the bandwagon.

Ira talks to Decrypt Media editor-in-chief Dan Roberts, and LA-based artist Vakseen about the appeal, and how NFTs are bringing new audiences both to the blockchain economy, and artists themselves.

Dan Roberts is Editor-In-Chief of Decrypt Media in New York, New York.

Otha Davis III (“Vakseen”) is a painter and digital artist who has been selling his work as NFTs since 2019. He’s based in Los Angeles, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday”. I’m Ira Flatow. There’s a new acronym in town this year, NFTs, or Non-Fungible Tokens, which offer an electronic certificate of ownership for digital artworks, music videos, even the New York Times finance columns. For some artists, the NFTs are paying huge dividends. Digital artist Beeple sold one of his works as an NFT for a $69 million. And now eBay will allow sales of NFTs on its online auction site.

The NFT world is a mix of gimmickry and creativity, and there are dozens of marketplaces designed to showcase both serious digital artists and more whimsical-seeming offerings, like a token of the venerable 2011 meme known as nyan cat, which sold for, wait for it, over $500,000. So what role do NFTs play in the art world, moving forward? Here to help unpack where NFTs came from and how they’re making waves in art and elsewhere is Dan Roberts, editor-in-chief of Decrypt Media, a new site dedicated to cryptocurrency. Welcome to “Science Friday”.

DAN ROBERTS: Thanks for having me on, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: For people trying to get their head around just what an NFT is, what is this non-fungible business all about?

DAN ROBERTS: Well, first of all, we can start with the non-fungible part. And the easiest way to describe it IS if I pull $1 bill out of my wallet and I hand it to you and you hand me one from your wallet, we each still have the same thing. We each have a dollar. That is a fungible asset.

The non-fungibility of these tokens is the idea that they are provably, verifiably unique, can’t be duplicated, copied, stolen, parked on blockchain, which, of course, you have to step back and understand blockchain, this immutable, peer-to-peer decentralized ledger that has no middleman, no one governing, controlling party or person. And in terms of the tech, these are digital tokens that exist on the Ethereum blockchain, but they’re not cryptocurrencies. They represent deeds to an asset.

And although we mostly right now discuss them as being digital assets, they can also represent deeds to a physical asset. You can tie an NFT to a physical artwork that is sitting somewhere in a museum or in a gallery. So really think of them as digital, provably scarce certificates of authenticity. The analogy I like, Ira, is I remember years ago, I would go to the physical sports collectibles store.

And you would look at Ted Williams jerseys and autograph balls. And if you were going to buy something from that store, you would expect a certificate of authenticity guaranteeing that the autograph is right. And this just puts that concept on blockchain.

IRA FLATOW: And the amazing amounts of money that people are asking for. I guess the value of any item, even if it’s a token, is what people are willing to pay for it.

DAN ROBERTS: Well, that’s exactly right. And a lot of people just can’t quite wrap their heads around the sky-high sums that some of these are fetching. It’s hard to understand paying $69 million for a digital-only image. People used to the old art world say, well, can I display it on my wall. And hypothetically, you could, but that would kind of defeat the purpose.

But you nailed it. Value is whatever the group says. And even though so many people look at the NFT art boom and they say, well, this just seems stupid, well, enough people think that there is value here.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go back to the art world, which is where so many of these NFTs are being sold now. We talked about how NFT– and you showed us– is a proof of ownership but not ownership the same way someone might own a Picasso, right?

DAN ROBERTS: Yeah, what you’re getting– I guess it’s fair to think of it as a URL. That puts it in terms that everyone knows, although it’s not quite exactly right. But you are getting an address to the digital asset that is parked on blockchain. But it’s really just an address that is linked to the item, which, in many cases, uncertain NFT art marketplaces, websites, is being stored somewhere else, and that’s a problem some people have with it.

That is many of these marketplaces are not actually storing the artwork on chains, so to speak. Basically, because you have the address and it’s in your digital wallet, you are the only one who can move it. So when we talk about ownership, it just means that you’re the only one with the keys to actually sell that object again.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I know that your media platform Decrypt has written about using NFTs for everything from music sales, to publishing novels, and short stories. What do creators like about this way of selling their work?

DAN ROBERTS: It depends whom you ask. But I think the pie-in-the-sky proposition that artists right now love, especially musicians, is the idea that, with most NFT marketplaces, every time the NFT is resold or every time copies are minted, which you can allow when you create the original, if you wish, a cut goes back to the original creator.

And artists on Spotify really do not earn much per stream. It’s like less than one penny. So if you’re a musician and you find out– say, you’re Kings of Leon or, say, you’re Weezer, who’s about to also do NFTs, you find out that you could, when you create your next album, create NFT versions, now you are doing a number of things at once.

You’re boosting engagement with your hardcore fans, who really love you and want to collect all the different things you’re offering. You’re selling more copies, and you’re getting more of a cut of the revenue because, when you create the NFT, you can say, we’ll also allow 100 other versions to be sold. But every time someone sells it, we get 10% of that cut because we’re the creator. The pie-in-the-sky goal here is get more money to the original creators, and who wouldn’t be on board with that?

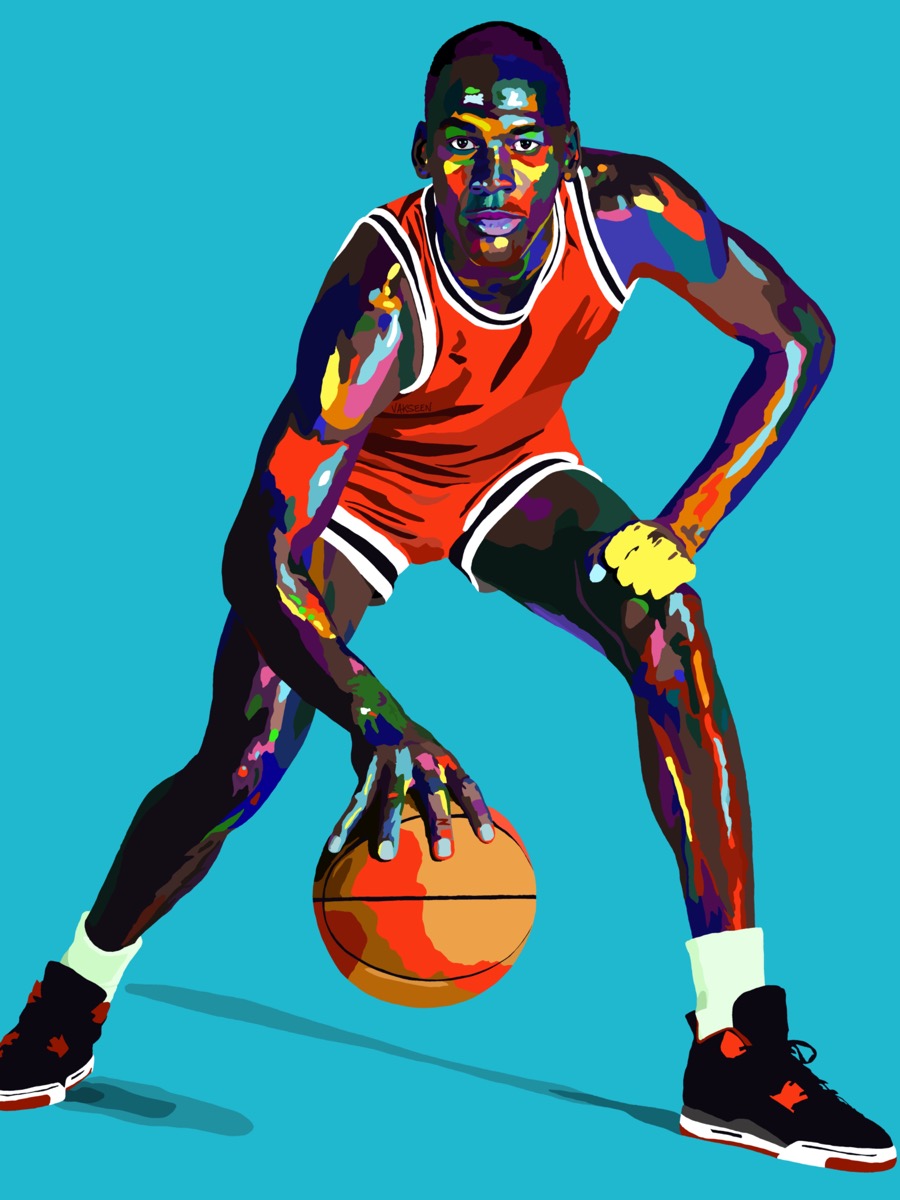

IRA FLATOW: I want to take a minute to talk to one of those creators of NFT art, Otha Davis the Third, also known as Vakseen. He’s a painter and now NFT artist, incredible stuff. And he’s based in Los Angeles. Earlier this year, an NFT of his portrait of basketball player Michael Jordan sold for $16,000. And it’s just one addition of several that have been valued that high. Welcome to “Science Friday”, Vakseen.

VAKSEEN: Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Tell us a bit more, first of all, about the art you make. I look, and I see these gorgeously colorful portraits of Billie Holiday, Kamala Harris, George Floyd, and more. But believe me, I’m not an artist here. [LAUGHS] How would you describe what your paintings look like?

VAKSEEN: Vibrant is definitely the first word I would use– colorful, fun, very energetic. There’s a lot of feeling and emotion in my work. My work celebrates pop culture. It celebrates Black pop culture, more specifically. I celebrate moments that kind of connect us all and bring us all together.

IRA FLATOW: What made you decide to enter the NFT world in the first place?

VAKSEEN: I work pretty exclusively with MakersPlace, one of the premiere NFT platforms. And they came to me before the site was live. For me, it just made sense. I’ve always kind of considered myself a futurist as it pertains to the things that I love and that I’m passionate about.

I had no clue what I was doing, but it just sounded like something that was cool, that could be beneficial in the future. I’ve been a part of the crypto art scene since 2018. It’s just now becoming hot and popular, but I’ve been a part of it before it was something that you could actually see.

IRA FLATOW: And what do you find different about this art space, about selling, about being part of it, the advantages, the disadvantages?

VAKSEEN: It opens the playing field, you know. It’s removing that third party. Traditionally, in the art world, you need a third party to help you, a gallery that’s going to help you get your work sold. Most artists don’t have a business mind. They don’t understand the importance of marketing and those type of things, so they partner up with a third party.

And that third party ends up taking 50% of the sales. I can tell you, as a working fine artist, the 50% commission model is something that never really sat with me that well. It just didn’t make sense to give away 50% when someone did not invest that much time in the creation. NFTs are totally changing the field. You can sit in the comfort of your home and sell your work to somebody on the other side of the world. Yes, a platform is going to get a cut, but it’s a much smaller percentage.

The art world can be pretentious at times. It can make people feel like they’re not welcome, and the NFT community, the NFT space it’s unlike any community I’ve ever experienced. The people involved, the passion, it feels very artist centric, and there’s just a lot of love and community, people celebrating and uplifting each other. And that’s a beautiful thing.

IRA FLATOW: You were featured in an article recently about how Black creators, specifically, are finding NFTs better for them then other ways of selling their art. Can you speak more about that?

VAKSEEN: There are just so many barriers in place within the traditional art world. We’ve been omitted from art history. Even as a successful working artist, I’m almost always the only Black in a show, in a physical show.

I live in Los Angeles. This is a very diverse city, an incredibly diverse city. It just– it speaks tremendously to the ways of the art world, these old ways, these old traditions.

The NFT scene is just breaking these barriers down. I’ve seen people be able to pay off their debts, buy homes for their parents. I’ve seen life-changing things happen, and we’re still in the early stages. Even myself, I’ve been able to open an art gallery behind NFTs, and I don’t I think that’s going to happen in that same space within the art world, within the traditional art world. It’s just not set up for us to succeed in that fashion.

IRA FLATOW: So then would you recommend people struggling in the traditional art world to make the switch and go to NFTs?

VAKSEEN: I don’t think it’s about a switch because I think any intelligent artist will make sure that they have a presence in the physical space as well as the NFT space. And that’s– myself, that’s the model that I’ve created. So I don’t think it’s a matter of switching. I think you should continue doing what you’re doing in the real world.

But you need a presence in this new NFT space, absolutely. It’s the future. And any artist that I know, I’ve been screaming this for the past few years. It’s pop now. It’s everywhere. It’s hot. It’s the thing to do. So now, everybody’s trying to get into it and rightfully so. Artists should be tapped in but in both spaces.

IRA FLATOW: Vakseen, thank you for this side of artistry that we have never seen before, this, as you say, so new and giving us a glimpse of what NFTs are like and what it’s like to be involved with them. Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today.

VAKSEEN: Oh, my absolute pleasure. Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: That was LA-based artist Otha Davis the Third, known as Vakseen. You can find links to his work on our website at ScienceFriday.com/NFT. Getting back now to Dan Roberts, editor in chief of Decrypt Media, let me play a clip from a long-time digital artist Rebecca Allen who has a concern about the direction NFTs are taking.

REBECCA ALLEN: NFTs feel like a financial product so much that an art is the product, is one product that people are investing in. And I just– for me, that’s never a vision of art that I wanted. And so I’m hoping it doesn’t expand in that way because it doesn’t have to. If there’s enough force from a side of just, let’s release the art–

IRA FLATOW: She’s talking about her fear here, right? That NFTs are going the way that much of global art trade already has, that means art as an investment and another kind of stock for rich people as opposed to allowing more access as more middle-class prices. Do you think she’s right?

DAN ROBERTS: Well, let’s remember, Ira, this has been a concern in the traditional art world, too, that fancy art and art collecting is just for the ultra rich, right? So in some ways, we’re just going in a full circle when we talk about these concerns. Now, in the NFT space in general, yes, some of the people paying the biggest prices– for example, the Beeple $69 million sale– well, the buyer was MetaKovan, who is in the NFT world and has made crypto riches. So it’s a bit of a misleading example, right?

And my point being, yes, some of the biggest NFT have just been to rich venture capitalists or billionaires like Mark Cuban. But that said, that’s why I think Top Shot is interesting. That’s a place where you can get a pack of those NFT moments, they call them, video clips that really are just highlights for as little as $9. And some of the collectors aren’t rich people. They’re just young kids who like the NBA, and they think it’s cool to own one of them.

IRA FLATOW: Galleries and museums have been finding ways to display other kinds of digital art for decades. Are they going to adapt to NFTs?

VAKSEEN: Well, it’s a fascinating question. I think, yes, they will. And in fact, we at Decrypt sent one of our reporters to a physical art gallery displaying NFTs that already popped up. And he wrote a very funny review about how it just was like any other art gallery. And maybe that’s fine, although does it defeat the purpose? The whole value proposition of NFTs is you’re trying to get people to wrap their minds around not being able to hold and touch the physical object and accept that value has gone digital.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow, and this is “Science Friday”. In case you’re just joining us, we’re talking about non-fungible tokens and the art world. Cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies also have an environmental impact. Some like Bitcoin take lots of energy to manage.

Elon Musk said just this week that Tesla would stop accepting Bitcoin for this reason. NFTs use a different system, right? Ethereum. But could a high carbon footprint still sink them?

VAKSEEN: Well, it’s a good question right now, Ira, and a lot of people in the mainstream have simply seen headlines. And thus, they are dismissing NFTs entirely. You’re now even seeing some artists shame other artists for minting an NFT because people say, well, aren’t they killing the environment?

And like most things, the truth lies somewhere in the middle. There’s been a lot of hyperbole. What they’re really talking about when they talk about the environmental impact is the electricity usage of a Ethereum mining, and when you mint an NFT that first time as a token on Ethereum, it involves the mining process, which uses a lot of electricity.

But as you alluded to, Ethereum, the network, is in the process of shifting to a new mining method called proof of state that, without getting too technical, will use dramatically less electricity. I guess the real answer is a Ethereum uses a lot less electricity than Bitcoin currently. And soon, Ethereum will use even less once it shifts over.

But you’re not wrong. I’d say to the critics, mining Bitcoin and mining Ethe has an electricity usage. And I guess people have to decide long-term whether it’s worth it. But I would add that a lot of the comparisons drawn are a little bit misleading. There’s not quite an apples-to-apples comparison.

IRA FLATOW: One of the main reasons people like the ecosystem of blockchain-based technologies, NFTs, cryptocurrency, and so on is the idea of a worldwide decentralized system. It’s less reliant on single companies like Facebook. How are we doing on achieving that kind of decentralization?

DAN ROBERTS: Yeah, that is the big value proposition of the entire crypto space. You’re right. And a lot of the people who got into it in the first place loved that cryptocurrency cuts out the middleman. There’s no one bank or governing party. Most of it hasn’t happened yet. It’s a lot of talk.

Now, NFTs might end up being the first great example of that. And a lot of people are now painting NFTs as the newest doorway that might bring new entrants into the crypto space who’ve previously not been interested because it really is decentralized. That is in theory.

Now, that said, like a lot in the crypto world, there’s a caveat already. And that is that, if you go buy an NFT artwork, you’re probably buying it through an NFT marketplace. Well, now you’re using a middleman. And Pplpleaser, who is one of the most prominent NFT artists, she said she’d like to see the NFT space evolve to a point where you don’t have to buy the NFT through an art marketplace. You can even decentralize that process, but we’re not quite there yet.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, and when we are there, we’ll have you back.

DAN ROBERTS: Sounds good to me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Dan. Dan Roberts, editor in chief of Decrypt Media.

Copyright © 2021 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.