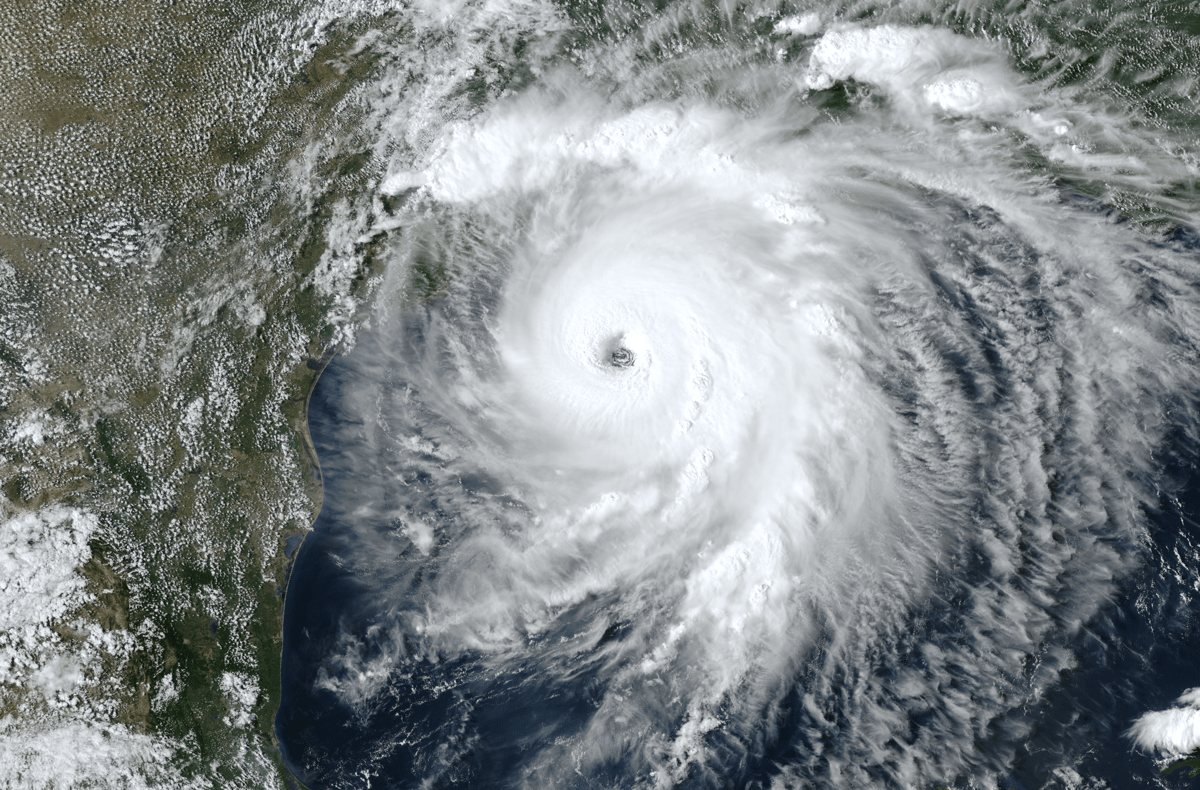

How Did Hurricane Laura Get So Bad, So Fast?

11:43 minutes

Hurricane Laura made landfall Wednesday night in Louisiana after strengthening from a Category 1 to a Category 4 storm in less than a day. As residents try to find shelter in pandemic-safe ways, meteorologists are warning of an “unsurvivable” storm surge reaching as far as 30 miles inland.

National Geographic editor Nsikan Akpan describes the factors that have caused the storm to so quickly gain strength. Plus, why recent changes to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations on who should get a coronavirus test and when people should quarantine are alarming epidemiologists and other experts—and other news from the week.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Nsikan Akpan is Health and Science Editor for WNYC in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. It’s been an historic and devastating weather week. Hurricane Laura smashed ashore in the Gulf with 150 mile per hour winds, storm surge, and predicted unsurvivable conditions. We haven’t ever heard that, I don’t think. And historic because of two storms in the Gulf at the same time.

Here to talk more about the rare, nearly record-breaking double feature, and how a storm like Laura can get so fierce so fast plus this week’s other science news is Nsikan Akpan, Science Editor for National Geographic, based in Washington. Welcome back.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Hi, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You have to talk about the storm. Residents of the Gulf and other inland areas are still dealing with the flooding and the wind damage from Laura, as we speak. And it turns out of the two storms there, Laura was the one to worry about. Right?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah. Absolutely. You know, every August I feel like I switch from being a science journalist to being a meteorologist for about two to three months, especially in the past few years. And it isn’t looking great.

Hurricane Laura smashed ashore near Cameron, Louisiana just after midnight on Thursday. It’s wind speeds were just shy of making it a Category 5. But it’s still going to go down as the most powerful hurricane to hit this section of the Gulf Coast since records started being kept in 1851.

As you described, officials said that the storm surge would be unsurvivable. And that surge stretched from near Port Arthur, Texas to Intercoastal City, Louisiana. So that’s more than 100 miles of coastline.

When I checked the tide trackers, water levels rose 6 to 10 feet when Laura made landfall in that region. And the National Weather Service predicted that this surge could penetrate up to 40 miles inland. And the thing is that flooding will likely last for days to come.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. How does a storm go from a 1 to a Category 4 in less than 24 hours?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, it’s remarkable. Philip Klotzbach, a Colorado State University meteorologist said it tied the fastest intensification on record, which was set by Hurricane Karl in 2010. And Laura’s gusto was fueled by a bunch of things. But the biggest factor was probably warm waters, which were 1 to 2 degrees Celsius above normal as the storm was churning through the Gulf.

IRA FLATOW: That was, like, what, 90 degrees in the Gulf, the water?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah, it’s about that exactly. That was the temperature. But relative to average temperatures in the Gulf, it was about 1 to 2 degrees more. And that’s surprising. Because Hurricane Marco had just passed through the Gulf earlier this week.

And the thing about hurricanes is that they tend to sop up heat as they go along and then cool off the sea. But despite Hurricane Marco likely siphoning off some of that energy, Laura still was able to come through and hit with a fury.

And I know what everyone’s probably thinking right now, as they listen to this, global warming. But it will take time for researchers to really decipher the degree to which climate change influenced this storm. But this is what we’re expecting. We’re expecting this type of pattern as the years go on. Warm waters are going to keep fueling these mega storms.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. They say it’s not more storms, it’s just more intense storms.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Exactly. And even though people are looking to the future to see this pattern, it really feels horribly familiar right now. Last year Hurricane Dorian rapidly intensified just before devastating the Bahamas. And the same happened with Hurricane Michael and Hurricane Florence in 2018.

I think what people need to know, unless you witness it firsthand, it’s very hard to fully grasp how long a hurricane’s devastation lingers after the storm is gone, after the TV crews sort of go away. In 2018, I reported from a hard hit town along the Carolina coast about a month after Hurricane Florence. And outside every home was just a pile of mattresses, you know, couches, framed pictures, pianos. I saw a piano.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. When we had Hurricane Sandy coming up years ago, and we understand that. It took years to recover. Still people still have not recovered from that.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Exactly. And it takes everything from a home, you know? When we talk to people down there, they’re just, like, this is my home. I want to rebuild. But I don’t know if I want to do it if another storm is just going to come through and knock everything out again. And I think you see that echoed in the early footage from Lake Charles, Louisiana and a lot of the places around where the storm made landfall.

And we’re not done, right? The forecasters are expecting this to be an extremely active hurricane season in part because La Niña, the climate pattern cousin of El Niño, is about to form and that helps promote cyclones. And we’ve already broken the records this year with nine named storms before August. And the conditions are so primed that forecasters say that we might even have to turn to the Greek alphabet to name all the storms that we have this year.

IRA FLATOW: Amazing. And of course, this all comes in the midst of a pandemic.

NSIKAN AKPAN: That’s exactly right. If people visit NationalGeographic.com right now, they can see a story by my colleague Sarah Gibbons that dives into how COVID-19 is cutting off access to storm shelters and basic necessities that people need after a hurricane like this.

IRA FLATOW: And speaking of the pandemic this week, a lot of us were, I don’t know if puzzled is the right word here, when the CDC announced earlier that it was no longer recommending people without COVID symptoms to be tested. And they followed that up by removing the recommendations for travelers to quarantine for 14 days. Why would either of these things be a good idea?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah. If I had long hair, I would be sort of pulling it out. And I think–

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHING]

NSIKAN AKPAN: –members of public health Twitter sort of feel the same. There’s been a real, real frenzy after these decisions came through. I mean, the first one, sort of saying that people who think they’ve been exposed to COVID-19 don’t necessarily need to be tested if they’re not showing symptoms, it really doesn’t make sense.

And also the way that the policy was put out. It was very quiet. It was a very quiet change. I think that’s led to a lot of the uproar.

And The Washington Post reported that the pressure to make the change came from the White House. And after a fact, there was an official from the Health and Human Services that said, doctors on the Coronavirus Task Force, all the physicians on our Coronavirus Task Force had endorsed the plan.

But then later Anthony Fauci told CNN, well, what are you talking about? You know, I was in the hospital last week receiving vocal cord surgery. And to quote him, he said, “and was not part of any discussion or deliberation regarding these new testing recommendations.”

But I think the bigger issue is that, again, it really doesn’t make sense to do this. If you went to a doctor and said, hey, I think my friend just poisoned me, and the doctor replied, sorry, I can’t test you until you show symptoms. You’d be, like, wait, what? That doesn’t make any sense. Like, I’m in trouble now.

I mean, early detection is even more urgent with COVID-19 because we know that up to 40% of cases have no symptoms. The American Medical Association replied to this news saying, this is a recipe for community spread and more spikes of coronavirus. And the same goes for the other new guideline about how travelers don’t need to quarantine if they’re coming from a place that is a hot spot for a disease.

Why would you do that? We know that these arrivals are more likely to have the disease. And, again, a lot of those people could be asymptomatic. It’s just extremely dangerous.

And we have a story out this week from one of our writers, Craig Welch, where he talked to experts across the country and their recommendations were incredibly uniform, right? We still just need to do the basics. And I think part of doing that is embracing reality. We’re half a year into the worst public health crisis in a century.

Aren’t people tired? Don’t people want to sort of go back to the way things were if they can, as fast as they can? So I think to do those things, we just really need to focus on the basics, wearing masks, social distancing, and also we need our leaders to have a uniform plan that they can give to us. Because creating all this confusion is just going to lead to more spread of the disease.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s see if we can end on a happier or a more hopeful note. A new story this week, and that is a ray of good news from the fight against a different infectious disease. The African continent was declared free of wild polio this week. Can you explain that?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yeah. I mean, this is the end of a 24 year effort to eradicate wild polio, which you know is a devastating disease. It’s a crippling disease. There was a major campaign that was launched in 1996 called the Kick Polio Out of Africa campaign. And back then, polio used to paralyze about 75,000 children on the continent per year. And through a public health outreach and through a mass vaccination campaign, they were able to reach this point where now wild polio has been eliminated from the continent.

IRA FLATOW: So there’s still a non-wild strain of polio left, right? How big a worry would that still be for this effort, to eradicate it?

NSIKAN AKPAN: Yes. I mean, even with this progress against wild polio, there’s still a strain of polio that’s circulating due to an old vaccine that involved a weakened version of the polio virus. And unfortunately, what happened is some people took that vaccine. And the virus sort of came alive again.

And now we have this other strain that doesn’t cause that many cases, you know, we’re talking about 320 last year, about 68 in 2018. But it’s still out there. And we’re still working to immunize with the polio vaccine that we know works now to fully eliminate that other strain. And the pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has sort of interrupted some of those efforts this year. And people are hoping that we can pick them back up once COVID-19 abates.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Nsikan.

NSIKAN AKPAN: Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Nsikan Akban, Science Editor at National Geographic in Washington, DC.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.